Increasing brutality in Egypt requires changing tactics in response

Egyptian civil society is under increasing attack by the state. Activist Sara Alsherif considers the actions taken by the informal group No Military Trials for Civilians and its partners to this crackdown. She notes how these strategies have been adapted over the course of the last seven years to respond to the constantly changing political reality of two parliamentary elections, two presidential elections, one massacre and one military coup. As police brutality and state surveillance increases, Sara notes how flexibility and creativity both on and offline is key to keep one step ahead of the authorities.

Despite hopes of a reprieve after the Egyptian Revolution in 2011, the crackdown on Egyptian civil society has been relentless. In late 2011, Egyptian authorities raided 17 non-governmental organisations (NGOs) working on democracy and rights issues. Then, in June 2013, 43 foreign and Egyptian NGO workers were sentenced to prison terms of between one and five years.11. “Egypt Must Overturn Jail Sentence for NGO Workers,” Amnesty International, June 5, 2013, accessed December 5, 2017, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2013/06/egypt-must-overturn-jail-sentence-for-ngo-workers/. In 2014 the Ministry of Social Solidarity issued a deadline requiring all civil society organisations to register with the government or face legal action.22. “From Bad to Worse: Looming Deadline Compounds Egyptian NGOs’ Woes,” Amnesty International, August 31, 2014, accessed December 5, 2017, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2014/08/bad-worse-looming-deadline-compounds-egyptian-ngos-woes/. And in 2015, investigative judges ramped up pressure on Egyptian human rights groups, using arbitrary travel bans and arrests.33. “Background on Case No. 173 - The “Foreign Funding Case” Imminent Risk of Prosecution and Closure,” Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights, March 21, 2016, accessed December 5, 2017, https://eipr.org/en/press/2016/03/background-case-no-173-%E2%80%9Cforeign-funding-case%E2%80%9D.

Most recently, in 2017 President Abdel Fatteh el-Sisi approved the Law 70 of 2017 for Regulating the Work of Associations and Other Institutions Working in the Field of Civil Work (the NGO law). This law prohibits NGOs from conducting activities that “harm national security, public order, public morality, or public health.”44. “Law of Associations And Other Foundations Working in the Field of Civil Work,” Articles 13 and 62 (2017). It creates a National Authority for the Regulation of Foreign Non-governmental Organisations,55. Ibid, chapter six. which has representatives from Egypt’s top national security bodies – the General Intelligence Directorate and the Defence and Interior Ministries – as well as representatives from the Foreign Affairs Ministry and the Central Bank of Egypt. The authority will oversee the work of NGOs, including any funding or cooperation between Egyptian associations and any foreign entity.66. Ibid, Article 71. In addition, the law prohibits any Egyptian government body from making agreements with NGOs without the authority’s approval, thereby controlling the funding of NGOs. The law also gives the government the authority to monitor NGOs’ day-to-day activities, from their choices for leadership to the scheduling of internal meetings. Relocating an NGOs headquarters to another building without informing the authorities is punishable under the law.77. The law punishes a host of violations with sentences of one to five years in prison and a fine of 50,000 to 1,000,000 Egyptian pounds (US$ 2,760 to US$ 55,349).

And as I write this paper I am trying to look for the NGO law online.88. “Egypt’s President Ratifies New NGO Law,” Ahram, May 29, 2017, accessed December 5, 2017, http://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/1/64/269799/Egypt/Politics-/Egypts-president-ratifies-new-NGO-law-.aspx; “Unofficial Translation for Law No (70) of 2017 of The Law of Associations And Other Foundations Working in the Field of Civil Work,” ICNL, 2017, accessed December 5, 2017, http://www.icnl.org/research/library/files/Egypt/law70english.pdf; “Egypt: New Law Will Crush Civil Society,” Human Rights Watch, June 2, 2017, accessed December 5, 2017, https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/06/02/egypt-new-law-will-crush-civil-society. Many results appear in the search engine from news websites and NGO websites but when I try to open the links they do not open. Despite the legislative restrictions outlined above, the online sphere has always been an area where we have celebrated victories, where we have mocked and objected to politicians. And in 2010-2011 the virtual world helped move events in the real world. Khaled Saeid’s story and the online campaign that followed helped fuel the Egyptian revolution.99. For more information about the death of Khaled Saeid and the Egyptian revolution, see: “The Price of Hope: Human Rights Abuses During the Egyptian Revolution,” International Federation for Human Rights, May 2011, accessed December 5, 2017, https://www.fidh.org/IMG/pdf/Egypte562a2011-1.pdf.

But in mid-May 2017, the government blocked access to at least 21 news sites because they were “spreading lies” and “supporting terrorism”.1010. Ruth Michaelson, “Egypt Blocks Access to News Websites Including Al-Jazeera and Mada Masr.” The Guardian, May 25, 2017, accessed December 5, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/may/25/egypt-blocks-access-news-websites-al-jazeera-mada-masr-press-freedom. This was swiftly followed by the blocking of many VPN websites, some online publishing platform sand blogs. According to an AFTE report1111. “Decision From an Unknown Body: On Blocking Websites in Egypt,” AFTE, June 4, 2017, accessed December 5, 2017, https://afteegypt.org/right_to_know-2/publicationsright_to_know-right_to_know-2/2017/06/04/13069-afteegypt.html?lang=en. the number of blocked websites has risen to at least 434. So we activists are being blocked from operating both online and offline.

But we refuse to be blocked.

The history of this crackdown is our history and through various methods we have resisted it, adapting ourselves and our tactics to ensure we stay one step ahead of the authorities. This contribution will examine how we have done that in the hope that others can learn from our methods – in the spite of adverse conditions, there is always room to react.

During the January 25 Revolution 2011, army forces began to be deployed throughout the country. Between January and August 2011 the number of civilians who faced military trials reached 12,000.1212. “The Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies and the No Military Trials for Civilians Group Joint Written Intervention to the 20th session of the UN Human Rights Council Item 3 - Interactive Dialogue with the Special Rapporteur on the Independence of Judges and Lawyers,” Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies, 2012, accessed December 5, 2017, http://www.cihrs.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/Military-Trials-of-Civilians-in-Egypt-since-the-January-25-Revolu. Hear more about military trials for civilians: TahrirDiaries, “٣ أعوام .. ٣ أنظمة .. المحاكمات العسكرية مستمرة "English".” Youtube video, 4:28. Posted March 12, 2014, accessed December 7, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gvbVStRfxJk&t=4s. Since then, the military’s jurisdiction has been expanded, largely under the guise of anti-terror rhetoric. In 2014, the current President el-Sisi passed law 136/2014, which enables military trial of crimes committed at public buildings, including roads and universities.1313. “15 Independent Rights Groups Condemn the Expansion in the Jurisdiction of Military Courts,” EIPR, October 30, 2014, accessed December 5, 2017, https://eipr.org/en/press/2014/10/15-independent-rights-groups-condemn-expansion-jurisdiction-military-courts.

No Military Trials for Civilians (NMTC)1414. “Death Sentence by Military Court. Irreversible Injustice,” No to Military Trials for Civilians, 2016, accessed December 5, 2017, http://www.nomiltrials.org. is an informal group, comprised of volunteers, that was founded in Egypt in April 2011 to resist this method to silence Egyptian civil society. The group works as a platform through which families of civilians facing military tribunals can get legal aid from human rights lawyers, plan and execute a campaign for their cases and receive aid to buy provisions for their detained loved ones. We also lobby for legal and constitutional amendments aiming to protect civilians from unjust trials and for the re-trial of those who have already been sentenced in military courts in addition to compensation for them.

The fact that our organisation is informal is, in itself, a strategy that has contributed to our success, although this was not a conscious strategy when we founded the group in 2011. At that time, we did not see a need to register the group – we depended on volunteer activists and lawyers. In order not to stigmatise ourselves, we did not want to use foreign funding. Instead, partner NGOs support the legal costs of defending the victims and we rely on in-kind assistance to help the victims’ families. Consequently, we remain unregistered, and have no fixed headquarters or offices. We are able to operate off the radar of the authorities who would probably like to see us shut down. Instead, we work from each other’s houses, from restaurants and cafes. Prior to the clampdown on NGOs we would meet in the offices of NGOs that were part of our group. Anyone who has the same objective of ending military for trials for civilians can join us – and in that sense we are very open. A lot of our discussions take place online, allowing everyone in the group to participate, although a core group eventually takes the decisions. Although this informality brings many benefits, we must also deal with the challenges that this brings, such as the inevitable impact on the stability of the group and effectiveness of the work we do.

In 2011, we had relative freedom, because the revolution had just happened. We used the streets and government offices as locations for protesting and expressing our views. Protest has been a key tool for the group including in Tahrir Square and in front of the military court in Cairo. We launched “Unjust Saturdays”1515. A group of mothers of civilians detainees who has been referred to military tribunal, gathered themselves every Saturday in front of the Ministry of Defense to demand the release of their relatives, and they called this day Unjust Saturdays. for mothers of civilians sent to military trials. The group protested weekly in front of the Ministry of Defence headquarters. As a result of the use of demonstrations as a tool of pressure, many activists have been released following their referral to the military court, including, for example, Amr El Behairy.1616. Zeinab El Gundy, “Amr El-Behairy Finally Wins Retrial in Egypt Military Court.” Ahram, January 10, 2012, accessed December 5, 2017, http://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/1/64/31402/Egypt/Politics-/Amr-ElBehairy-finally-wins-retrial-in-Egypt-milita.aspx.

Protest as a method of resistance was not much affected by Mohamed Morsi’s regime. NMTC was able to highlight, with considerable success, the plight of civilians facing military trial. The most significant event for us during his regime was in November 2012 when military forces landed on one of the inhabited islands in the middle of the Nile (Al Qursaya) to capture it. When the people living there tried to resist, one was murdered and 22 were sent to military trials.1717. “Egypt Island Residents Forcibly Evicted,” Al Jazeera, January 20, 2013, accessed December 5, 2017, http://www.aljazeera.com/video/middleeast/2013/01/201312053748872344.html.

There was zero media coverage for the case until the NMTC started to work on it by going to the island, and organising protests with families of the detainees in front of the supreme court. We also organised an event where we spent a whole day with the families and children of the detainees in their homes, while the military forces were on the opposite side on one of the captured lands.

The pressure we created contributed to the administrative court ruling in favour of the people’s right to their land and homes, and to the release of the 22 detainees. They were either cleared of any charges or convicted with a 6 months prison sentence, which was how long they had already served since their initial arrest.

The August 2013 Rabaa massacre,1818. More details about Rab’a Massacre from Human Rights Watch report: “All According to Plan: The Rab’a Massacre and Mass Killings of Protesters in Egypt”, Human Rights Watch, August 12, 2014, accessed December 5, 2017, https://www.hrw.org/report/2014/08/12/all-according-plan/raba-massacre-and-mass-killings-protesters-egypt; “Egypt: Establish International Inquiry Into Rab’a Massacre,” Human Rights Watch, August 14, 2015, accessed December 5, 2017, https://www.hrw.org/news/2015/08/14/egypt-establish-international-inquiry-raba-massacre. in which the military killed more than 1,000 people opposing Morsi’s removal by a military coup in July 2013, was a turning point in how the Egyptian government dealt with public protests. Further reflecting this increasingly brutal attitude was the protest law,1919. Amr Hamzawy, “Egypt’s Anti Protest Law: Legalising Authoritarianism.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, November 24, 2016, accessed December 5, 2017, http://carnegieendowment.org/2016/11/24/egypt-s-anti-protest-law-legalising-authoritarianism-pub-66274. passed in November 2013. It essentially enables the government to cancel or postpone protests – one of the biggest threats to the victory of the January 25 Revolution. Consequently, we have been forced to alter our traditional protest strategy for fear of sustaining loss of life or injury to our supporters. We decided it was only safe to call smaller, discrete protests with a set time limit and which had no intention to confront the authorities.

In 2013 the Committee of Fifty (referring to the number of members) was established to prepare a new constitution. We saw this as an opportunity to pressure this committee to adopt an article in the new constitution prohibiting referring civilians to military courts.

In cooperation with other revolutionary groups and parties, NMTC lobbied the committee using social media to create a tweet storm in order to pressure the Committee of Fifty to hold a hearing for the NMTC. We worked on several levels. The first level was to pressure the members of the committee individually and through their social circles, as well as through professional groups they belong to such as unions or syndicates of journalists, artists, engineers, representatives of people with special needs, workers, etc. We also conducted one on one sessions with some members of the Committee of Fifty, whom we saw had moderate opinions regarding the issue. We also cooperated closely with human rights lawyers and activists to draft articles to be added to the constitution regarding military trials, which were sent to the committee members through registered mail.

The campaign pressure succeeded in obtaining a committee hearing. Three members of NMTC attended the hearing along with one of the victim’s family members. During the hearing, the entire military trials issue was discussed and we presented the draft constitution articles. Unfortunately, the Committee of Fifty’s representative of the Armed Forces declined to attend the hearing only two days prior to the scheduled date.

In addition to direct dialogue with the Committee of Fifty, on 26 November 2013, the day the committee voted on the article about military trials for civilians, we decided to apply further pressure by protesting in front of the parliament. Coincidentally, it was also the first day for the protest law to be enforced. The authorities reacted brutally – we protested for less than 20 minutes after which, most of us were beaten, harassed and arrested by the police.

The police brutality and the intense media coverage on both mainstream and social media, resulted in significant pressure to release us. This pressure was exacerbated due to the participation of members of the NMTC, who were mostly female, well-known, activists and who had met with most of the Committee of Fifty members before. Due to the pressure the police released NMTC members the following day in the middle of the desert. The lawyers and reporters, and some of the other protesters, were released a few days later. Others were not so lucky. The activist Alaa Abdel Fattah was arrested and accused of calling for the protest and attacking policemen, which is not true. He was sentenced to 5 years in prison. Since his arrest, we have campaigned for his release online, using the hashtag #freealaa, as well as in front of the Presidential Palace following el-Sisi’s inauguration.

Having already adapted the way we used protest, focusing on smaller, sudden protests, the police brutality during this November 2013 protest forced NMTC to stop using protest altogether as a strategy. The stakes were getting higher. The aggression by the authorities against any hint of a protest of, even if small with little impact meant that there was no guarantee that we were taking the risk alone and that no one else would pay for it.

However, following a particularly brutal police reaction, which resulted in the death of Shaimaa Al-Sabbagh, it was impossible not to react. Shaimaa was a leading member of the Socialist Popular Alliance Party. She was shot and killed by police, in broad daylight, in Cairo on Saturday when officers opened fire on a socialist rally near the capital’s Tahrir Square. She was participating with her colleagues in a symbolic protest where everyone held flowers.2020. “Egypt: Video Shows Police Shot Shaimaa al-Sabbagh,” Human Rights Watch, February 1, 2015, accessed December 5, 2017, https://www.hrw.org/video-photos/video/2015/02/01/egypt-video-shows-police-shot-shaimaa-al-sabbagh; see also Human Rights Watch, “Video Shows Police Shot Shaimaa al-Sabbagh.” Youtube video, 2:44. Posted January 31, 2015, accessed December 5, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uMBvbIojtWU; and “Final Moments of Activist Shot in Cairo,” The New York Times, February 3, 2015, accessed December 5, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/video/world/middleeast/100000003486953/final-moments-of-activist-shot-in-cairo.html?action=click>ype=vhs&version=vhs-heading&module=vhs®ion=title-area; “Egyptian Activist Shot and Killed During Peaceful Protest in Cairo,” Time, January 24, 2015, accessed December 5, 2017, http://time.com/3681599/egypt-activist-shaimaa-al-sabbagh-tahrir-square-shot-killed/.

This act of aggression by the police motivated many angry people to go back to the streets a few days later, to the same spot where she was murdered. Despite the threats from security forces and an extensive police presence, a large number responded to the call to protest.

The technique used to call for protesting might be the reason. The call was only for women who then put flowers where Al-Sabbagh was murdered. Despite the high police presence they did not attack the women, although instructed some civilians to clash with the protesters.2121. Maggie Fick and Michael Georgy, “Women Hold Rally in Cairo to Demand Investigation Into Protestor Deaths.” Reuters, January 29, 2015, accessed December 5, 2017, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-egypt-protests-women/women-hold-rally-in-cairo-to-demand-investigation-into-protestor-deaths-idUSKBN0L21FN20150129.

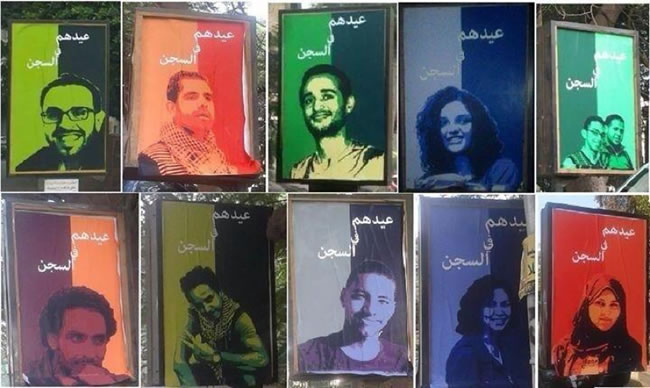

Despite this crackdown on protesting, through creative thinking, activists groups are still able to seize some public places. In 2014, for example, and after a wave of arrests of several activists from demonstrations under the protest Law, Egyptians woke up on the first day of Eid al-Fitr (one of the Muslim religious holidays where people feast) to find that a number of billboards had been replaced by photos of young men and women smiling and under each of them the words “Their Eid [Feast] inside jail”. Despite the supportive climate in Egypt at that time to the Authority, these banners aroused great sympathy towards those young people in prison.2222. Zeinobia, “Their Eid Inside Jail.” Egyptian Chronicles blog, July 18, 2015, accessed December 5, 2017, https://egyptianchronicles.blogspot.com.eg/2015/07/their-eid-inside-jail.html.

Billboards with photos of the prisoners with words “Their Eid (feast) in the jail”

NMTC and its partners also look internationally to help build solidarity for its cause.

We are still able to create noise that can draw attention to human rights cases and achieve international news coverage. As a result of the campaign following the death of Shaimaa El-Sabbagh, Egyptian police were forced to open an investigation into her death. And despite of attempts to charge others, the officer responsible for killing her was finally tried for 10 years.2323. “Egyptian Police Officer Jailed for 15 years Over Death of Protester,” The Guardian, June 11, 2015, accessed December 5, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jun/11/egypt-police-officer-jailed-15-years-death-protester-shaimaa-el-sabbagh-cairo; “Police Officer Sentenced to 10 years for Killing Activist Shaimaa El-Sabbagh,” Ahram, June 19, 2017, accessed December 5, 2017, http://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/1/64/271210/Egypt/Politics-/Police-officer-sentenced-to--years-for-killing-act.aspx. Other cases are less successful. For example, Mohammad Shawkan is a photojournalist who was covering the Rabaa massacre when he was arrested. He has not been released despite all the international pressure and clear case of innocence. Similarly, Alaa Abdel Fattah, who has been arrested under every president and who is currently unjustifiably in jail, while new cases are being filed against him, despite the international pressure to release him.

Unlike in the early years of the revolution, you will not find us activists on television, in newspaper interviews, in the corridors of the People’s Council, or in front of it demonstrating. And even if by chance official media talks about us it will be in the context of talking about the judicial rulings against us. We have been hidden by official state institutions! But we have not yet evaporated.

Together we work on creating new tools to overcome the narrowing of real and virtual spaces. In real spaces, this involves adapting our methods, changing the nature of protest and becoming cleverer. Online, we must stay one step ahead. Recently the government blocked the encrypted messaging app Signal.2424. Farid Y. Farid, “No Signal: Egypt Blocks the Encrypted Messaging App as it Continues its Cyber Crackdown.” Tech Crunch, December 26, 2016, accessed December 5, 2017, https://techcrunch.com/2016/12/26/1431709/; Mariella Moon, “Egypt Has Blocked Encrypted Messaging App Signal.” Engadget, December 20, 2016, accessed December 5, 2017, https://www.engadget.com/2016/12/20/egypt-blocks-signal/. This is an important tool for us – it guarantees secure communications without third parties being able to interfere. We developed our relationship with its parent company Open Whisper Systems and before long it was up and running again.2525. “Signal Bypasses Egyptian Authorities’ Interference with Update to Application,” Mada Masr, December 22, 2016, accessed December 5, 2017, https://www.madamasr.com/en/2016/12/22/news/u/signal-bypasses-egyptian-authorities-interference-with-update-to-application/. And in order to write this article I am now opening two different browsers, one of them for normal browsing and the other to access the blocked websites.

This creative thinking and adaptability that we must practise online is reflective of my reality offline. We will not be blocked online. And we will not be blocked offline. There is always a way and we must stay one step ahead.