Examining sustainable operating models for civil society

Around the world, civil society is at a crossroads. Buffeted on one side by questions about their relevance, legitimacy, and accountability from governments and their beneficiaries, civil society organisations (CSOs) face pressure to demonstrate their value to and connection with local communities. On the other side, civil society is having to adjust to a rapidly deteriorating legal and operational environment, as countless governments pursue regulatory, administrative, and extra-legal strategies to impede their work. Non-state actors also pose a threat to the sector, attacking human rights defenders, bloggers and journalists, environmentalists, and labor unionists in unprecedented numbers. Simultaneously, CSOs are encountering major disruptions to their revenue streams because of changing donor priorities and government restrictions on foreign funding, and to their business model from emerging forms of civic activism.

At this pivotal moment, CSOs can either adapt or hunker down, hoping that the tide of change will crest and dissipate. For those organisations intent on survival, there is an urgent need to find alternative models and approaches—even as they fight for their right to exist and receive funding. The crisis confronting the civil society sector creates an impetus for donors and civil society to jointly reexamine traditional approaches and reimagine what healthier, more sustainable operating models would look like. This article seeks to contribute to this conversation by assessing the strengths and weaknesses of various organisational forms on civil society’s sustainability and resilience.

Around the world, civil society organisations (CSOs) are under assault, as governments and non-state actors erect countless barriers to their work. For those groups intent on survival, business as usual will not suffice. The crisis facing the civil society sector creates an urgent need for CSOs and their partners to find alternative models and approaches, even while fighting for their right to operate freely and independently.

For the past three decades, civil society has proliferated all over the world. The expansion of human rights and free flow of global capital gave rise to a new universe of CSOs working in a variety of sectors.22. Edwin Rekosh, “Rethinking the Human Rights Business Model: New and Innovative Strategies for Local Impact.” CSIS, June 14, 2017, accessed November 20, 2017, https://csis-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/170630_Rekosh_HumanRightsBusinessModel_Web.pdf?NPh2vHwQCZCf2579BsSo41O0LqEsRUH3. These organisations offered novel opportunities to affect social change at a grassroots level and fill gaps in service delivery – and as a result, donors invested heavily in them.33. Edwin Rekosh, “To Preserve Human Rights, Organizational Models Must Change.” OpenDemocracy, November 28, 2016, accessed November 20, 2017, https://www.opendemocracy.net/openglobalrights/edwin-rekosh/to-preserve-human-rights-organizational-models-must-change. During this period of rapid growth, most organisations adopted a traditional business model in which they received resources from donors to implement projects, deliver services, conduct research, or execute advocacy campaigns.44. Rekosh, “Rethinking the Human Rights Business Model.”

While this funding model has served civil society well for 30 years, it is proving to be brittle when confronted with closing space. Increasingly, professional CSOs compete with new and emerging forms of civic activism. Advocacy organisations are often outflanked by social movements, which have proven more adept at mobilising broad cross-sections of society in highly fluid environments.

In addition, the grant-driven business model has been criticised for creating legions of elite, capital-based CSOs more connected to their donors than to the populations they serve. To be sure, CSOs have made heroic contributions to expanding human rights and holding governments, international organisations, and transnational corporations accountable for adhering to those norms. Yet, civil society’s reliance on foreign donors and lack of accountability to beneficiaries have made the sector susceptible to governments’ and extremists’ self-serving attacks.55. Shannon N. Green, “Violent Groups Aggravate Government Crackdowns on Civil Society.” Open Democracy, April 25, 2016, accessed November 20, 2017, https://www.opendemocracy.net/openglobalrights/shannon-n-green/violent-groups-aggravate-government-crackdowns-on-civil-society. These actors charge that CSOs are malign actors serving a foreign agenda, to the detriment of economic development or security in their own country. Another problem arises when funders’ foreign policy priorities change, leaving their local partners to fend for themselves.

For all of these reasons, scholars and practitioners have begun exploring alternative operating models to reduce CSOs’ dependence on foreign donors and weather the storm of closing civic space.66. The focus of this analysis is on models used by and relevant to local “social justice” CSOs - whether operating in the realm of human rights, development, environmental justice, or anti-corruption and transparency. This paper will not consider government-organised non-governmental organisations (GONGOs), international non-governmental organisations (INGOs) including those with local chapters, or organisations exclusively operating in cyberspace. This article seeks to contribute to this conversation by evaluating the attributes of different CSO business models and their relationship to sustainability and resilience. To do so, the author will use a holistic definition that looks at the ability of organisations to “continuously respond to national and international public policy variations, governance deficits, and legal and regulatory policies through coherent and deliberate strategies of mobilising and effectively utilising diversified resources, strengthening operations and leadership, promoting transparency and accountability, and fostering the scalability and replicability of initiatives and interventions.”77. Charles Kojo VanDyck, “Concept and Definition of Civil Society Sustainability.” CSIS, June 30, 2017, accessed November 20, 2017, https://www.csis.org/analysis/concept-and-definition-civil-society-sustainability.

Membership-based organisations (MBOs) have inherent traits that foster local buy-in, bolster their ability to adapt to shifting circumstances, contribute to transformative change, and influence government policy.88. For this paper, MBOs refer both to fee-based organisations and those in which members do not pay fees. They comprise more traditional forms of civil society such as trade unions, professional associations, etc. as well as social movements. Thus, they are well-positioned to withstand the current crisis of closing civic space.

Key to the legitimacy and sustainability of MBOs is their grassroots membership. MBOs form around the common interests, needs, and priorities of members and seek to leverage the size, diversity, and influence of their membership base to advance shared policy objectives. Because they are accountable both inward (as leaders are often elected or designated) and outward (as leaders represent their constituencies), MBOs can more easily respond to the needs and aspirations of their members.99. Nicola Banks, David Hulme, and Michael Edwards, “NGOs, States, and Donors Revisited: Still Too Close for Comfort?,” World Development 66 (February, 2015): 707-718, accessed November 20, 2017, http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0305750X14002939/1-s2.0-S0305750X14002939-main.pdf?_tid=77f2451c-8f25-11e7-9c92-00000aacb35f&acdnat=1504277854_4a0174e79f9017c1032fcb696097ff3e. This flexibility is critical in closed, closing, or shifting environments. In such contexts, governments cannot apply the same tactics used against formalised CSOs, such as cutting off foreign funding, threatening deregistration, or exposing the organisation to a lengthy, politicised audit.

Due to the benefits of this model, activists from Brazil to Egypt, India to Kenya are adopting looser, more organic, and less hierarchical forms of association and activism.1010. Richard Youngs, “Global Civic Activism in Flux.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, March 17, 2017, accessed November 20, 2017, http://carnegieeurope.eu/2017/03/17/global-civic-activism-in-flux-pub-68301. These approaches include online and offline activities, such as large-scale digital campaigns for social justice in Brazil, closed Facebook groups of women supporting each other to lead more independent lives in Egypt, student protests in India, and the formation of new umbrella groups comprising faith groups, trade unions, and academic bodies in Kenya.1111. Ibid.

This approach is not without risks. Governments are increasingly alarmed by the prospects of mass mobilisation and are resorting to draconian measures to curtail it. Particularly in settings in which space is closed or closing, even MBOs are constrained in their ability to overtly lobby for transformational change.

Despite these challenges, developing constituencies for civil society and mobilising the public are essential to protecting individual organisations and to defending democratic values more broadly. MBOs, including social movements, provide important avenues to reclaim the rights of association, assembly, and expression and to build more inclusive societies.

The barriers to foreign funding, decrease in donor support for human rights, and drawbacks of relying on foreign donors have led many CSOs to explore domestic revenue streams. This examination is long overdue. Beyond providing a financial lifeline, local funding can augment the sustainability of CSOs by building local constituencies and raising awareness of and support for their work.

Local funding – alternatively referred to as domestic philanthropy, community philanthropy, or domestic fundraising – takes many different forms. In some environments, a growing family of community philanthropy organisations, including community foundations, pool and distribute local resources for grantmaking, while in others, CSOs are acting alone to increase individual donations from ordinary citizens. However, underlying the diversity of these approaches are three shared elements: developing local assets, strengthening local capacities, and building local trust.1212. Mona Younis, “Community Philanthropy: A Way Forward for Human Rights?.” Global Fund for Community Foundations, February 2017, accessed November 20, 2017, http://www.globalfundcommunityfoundations.org/information/community-philanthropy-a-way-forward-for-human-rights.html.

With the expansion of the middle class in developed and developing countries, there is a broader pool of domestic resources for CSOs to tap into. Local philanthropic sectors are emerging in many parts of the world that were traditionally considered purely “aid recipient” countries, such as Serbia and South Africa.1313. Jenny Hodgson, “Local Funding Is Not Just an Option Anymore - It’s an Imperative.” OpenDemocracy, May 10, 2016, accessed November 20, 2017, https://www.opendemocracy.net/openglobalrights/jenny-hodgson/local-funding-is-not-just-option-anymore-it-s-imperative. This evolution has prompted a movement to grow domestic philanthropy, both as a strategy to shift grantmaking closer to the ground and as a way to encourage local giving.

One notable indicator of this mindset is the expansion of community foundations. These are grantmaking public charities that aim to solve discrete challenges within a defined local geographic area, pool financial contributions from individuals, families, businesses, and traditional donors to support effective nonprofits in their communities.1414. “Community Foundations,” Council on Foundations, 2017, accessed November 20, 2017, https://www.cof.org/foundation-type/community-foundations-taxonomy. Over the past decade, the number of community foundations has grown to 1,500 in more than 50 countries.1515. “Who We Are - The distinctive features of the Fund,” Global Fund for Community Foundations, February 23, 2011, accessed November 20, 2017, http://www.globalfundcommunityfoundations.org/distinctive-features/. While each foundation might look different depending on the local context, what unifies this model is the core belief that development will be stronger and more lasting when community members themselves are driving and investing their own resources in solutions.

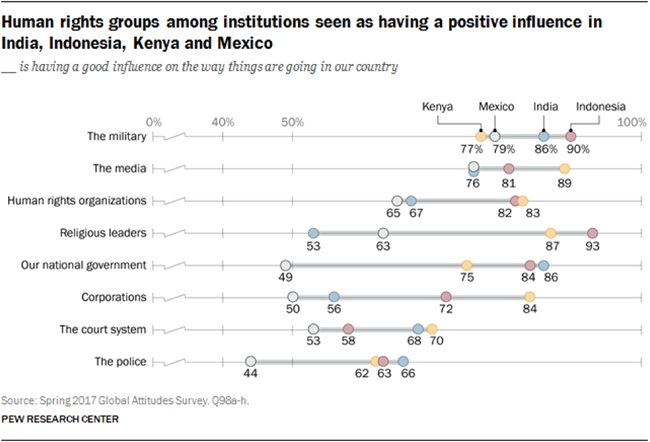

Another approach is to generate revenue from small, individual donations. Several cross-national surveys have shown the potential for CSOs to tap into broad public support and trust in local human rights organisations.1616. James Ron, Archana Pandya, and David Crow, “Can Human Rights Organizations in the Global South Attract More Domestic Funding?,” Journal of Human Rights Practice 8 (2016): 393-405, accessed November 20, 2017, https://jamesron.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Ron-Pandya-Crow-2016-Can-Human-Rights-Organizations-in-the-Global-South-Attract-More-Domestic-Funding.pdf. In a survey conducted by the Pew Research Center, a majority of citizens in India, Indonesia, Kenya, and Mexico said that human rights organisations have “very good” or “somewhat good” influence on the way things are going in their country.1717. Richard Wike and Caldwell Bishop, “Public Attitudes Towards Human Rights Organizations: The Case of India, Indonesia, Kenya and Mexico.” Pew Research Center, October 3, 2017, accessed November 20, 2017, http://www.pewglobal.org/2017/10/03/attitudes-toward-human-rights-organizations-india-indonesia-kenya-mexico/. This sentiment puts favourability for human rights organisations below the military and religious leaders but above or on par with corporations and police. Survey experiments conducted by James Ron, José Kaire, and David Crow also prove that “many people are in fact willing, if asked in the right way, to make small donations” to human rights organisations.1818. James Ron, José Kaire, and David Crow, “Ordinary People Will Pay for Rights. We Asked Them.” OpenGlobalRights, February 15, 2017, accessed November 20, 2017, https://www.openglobalrights.org/ordinary-people-will-pay-for-rights-we-asked-them/. These findings indicate that there is untapped potential for CSOs to replace or supplement their funding with contributions from individual donors.

Despite these promising signs, local funding is unlikely to replace foreign funding entirely. Substantial funding, primarily from northern sources, remains necessary to carry out much of civil society’s work.1919. Younis, “Community Philanthropy: A Way Forward for Human Rights?.” The Arab Human Rights Fund, for instance, was created with the intention of fostering local giving for rights work. More than a decade later, external funding remains the principal source of support for the fund and community foundations like it.2020. Ibid.

There are other constraints to applying this model across the board. Citizens may fear retribution from repressive governments for making contributions to CSOs, or legal constraints to local fundraising may make this strategy impossible. In Morocco and Oman, for example, soliciting for funding is illegal and could lead to charges of terrorism. Moreover, in these environments, wealthy individuals voluntarily avoid links with CSOs either “due to a mutually beneficial relationship between them and the dictatorship, or out of fear of repercussions against their economic interests.”2121. Hussein Baoumi, “Local Funding Is Not Always the Answer.” OpenDemocracy, June 27, 2016, accessed November 20, 2017, https://www.opendemocracy.net/openglobalrights/hussein-baoumi/local-funding-is-not-always-answer. Organisations that want to attract funding from local elites may have to bend to their priorities and preferences, giving them even less autonomy than if they received funding from a distant foreign donor.

CSOs – especially those working on sensitive issues like human rights – will have a hard time overcoming the structural and legal barriers in these highly repressive settings. Yet, overall, the rapid growth of community philanthropy and enduring public support for human rights ideas and organisations show that the potential for domestic fundraising has not even begun to be realised.

Given challenges with funding and sustainability, and a desire to end their reliance on donors, some organisations are experimenting with self-sustaining models based on a private sector mentality and approach. The essential attribute of these market-driven organisations is that they generate all or part of the resources they need to operate and contribute to social change out of their own activities.2222. Burkhard Gnarig, The Hedgehog and the Beetle: Disruption and Innovation in the Civil Society Sector (International Civil Society Centre: Berlin, 2015): 1-256.

There are many permutations of market-driven organisations, including those that are set up as commercial ventures but advance a social good (i.e., social enterprises), those that are registered as non-profit organisations but have income-generating activities, and everything in between. Social enterprises have grown in number and scale as a response to basic unmet needs or social problems that public sector or civil society strategies have failed to resolve. These ventures seek to apply business concepts – market analysis, business planning, raising capital, scaling up, and return on investment – to complex social challenges.

One of the best-known examples of the investment model – Grameen Bank – provides microcredit to the poorest of the poor to start their own small, income-generating ventures, with no requirement for collateral. With a total disbursal of US$18 billion in loans to 9 million borrowers, and a 95 per cent rate of repayment, Grameen is able to use the interest on loans to continue investing in lifting people out of poverty.

Pioneering CSOs are also creating business arms or offering fee-based services to subsidise or replace other revenue streams. Business activities can either be separate or integrated into the CSO. For example, Oxfam’s shops generate proceeds that are then funneled into the organisation’s poverty eradication efforts. Other CSOs leverage their expertise – in legal matters, organisational development and management, monitoring and evaluation, survey design and implementation, social media campaigning, etc. – and offer for-profit services to government agencies, corporations, and non-governmental organisations to subsidise their non-profit activity.

Finally, commission-based organisations collect nominal fees to link donors or service providers to beneficiaries. World Vision has long used this model – appealing to donors to sponsor a child for a fixed amount every month – to support its poverty alleviation efforts.2323. “Sponsor a Child With World Vision,” World Vision, 2017, accessed November 20, 2017, https://www.worldvision.org/sponsor-a-child. Donations are pooled with other sponsors to fund programmes that benefit the sponsored child and his or her community. In return, donors get to build a relationship with their sponsored child and the broader community. GlobalGiving has taken this approach into the 21st century, using an online platform to directly connect donors to vetted local organisations in 165 countries.2424. “How It Works,” GlobalGiving, 2017, accessed November 20, 2017, https://www.globalgiving.org/aboutus/how-it-works/. For a 15 per cent fee on donations, GlobalGiving sustains its operations and helps grow philanthropy around the world.

These models possess several attributes that make them more resilient to closing space. For one, all or part of their revenue is generated from customers or clients for whom they are providing a desired product or service. It is far more difficult to jeopardise this source of funding than it is for governments to cut off foreign grants. Market-driven organisations are also less vulnerable to fluctuations in foreign policy and donors’ preferences. Because they do not primarily rely on external support, they are not subject to the whims of changing administrations.

Despite these strengths, a market-driven model is not suitable for every organisation in every environment. Human rights and social justice organisations have missions and expertise that do not always lend themselves to marketable products or revenue-generating services. Furthermore, such a model does not help organisations cultivate domestic trust and support. Market-driven organisations do not have incentives to create broad-based constituencies, as the model is dependent on having customers and clients, not partners and champions. Without a strong and vocal constituency for their work, civil society is unlikely to be able to withstand the deluge of government restrictions and repression in this era of closed, closing, and shifting space.

Governments will find a way to shut down activity that they do not like, regardless of what form the sponsoring organisation takes. Registering and operating as a commercial enterprise does not provide full protection against government interference and intimidation. Egyptian organisations tried to avoid restrictions on civil society during the Mubarak era by registering as civil companies under commercial law. For a time, this allowed these organisations to circumvent stringent reporting requirements that traditional CSOs were subjected to. However, the Sisi government has sought to close this loophole and require all public benefit organisations to register as NGOs or risk closure or prosecution.2525. Saskia Brechenmacher, “Civil Society under Assault.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, May 18, 2017, accessed November, 20, 2017, http://carnegieendowment.org/2017/05/18/institutionalized-repression-in-egypt-pub-69959.

Market-driven models are also not proven vehicles for meaningful social change. They can effectively address service gaps, but their ability to transform the legal, regulatory, and enabling environment for civil society is unclear. These approaches, by their very nature, may not equipped to tackle deep social problems like inequality, discrimination, and injustice that CSOs exist to address.

As this paper illustrates, there are different models available for CSOs to test in order to build their resilience to government repression and position the sector for the future. MBOs have intrinsic features that allow them to adapt to shifting circumstances, continue to generate revenue, and survive even as foreign donors’ priorities shift and the legal and regulatory environment deteriorates. With broad and committed constituencies, MBOs can influence policy and engage in collective action to keep civic space open. Likewise, community-funded organisations have greater legitimacy and ability to advance structural reform given their deep community roots. Research and public opinion polls show the unrealised potential for CSOs to solicit donations from the population, thus making up for the loss of revenue from foreign donors. Finally, CSOs could look to the market for answers to the challenge of closing space. Market-oriented approaches provide opportunities to diversify revenue, tap into new sources of funding, think strategically about the demand for civil society services and products, and demonstrate impact with quantifiable measures. These traits are all beneficial for enhancing civil society’s sustainability and resilience.

In spite of these advantages, each model has limitations and downsides. There is no ideal organisational model that will allow civil society to persist in the face of closed, closing, and shifting space – and in many cases, organisations will continue to require external support. To withstand the onslaught of restrictions and survive a period of significant disruption, civil society and their funders will have to experiment with different models and pick and choose the attributes most relevant to their particular circumstances.

We are living through a perilous time for civil society. However, if CSOs and their partners are willing to take risks and exercise foresight, the global crackdown on civil society could engender much-needed innovation and renewal for the sector.