In the past several years, the world has been shaken by protests, peaceful and otherwise. Findings of recent research indicate that the leading cause of protests around the world is a broad set of grievances related to economic needs. However, the single demand that exceeds all others is what prevents progress toward economic justice: a lack of what protesters increasingly frame as “real” democracy. This holds true in political systems of all types, from the authoritarian to representative democracies old and new. Rights-based grievances are the driving force behind significantly fewer protests than those related to economic need, and the demands for economic justice that have dominated world protests in recent years have not been formulated in the language of rights. This article explores both why this might be so and how human rights practitioners might better understand the drivers of social unrest and the importance this holds for their work.

In recent years, the world has been shaken by protests, peaceful and otherwise. The Arab Spring, the anti-austerity protests throughout Europe, Occupy and the movement of the Squares around the world are well known to us because of the extensive international media coverage they have received. These protests were largely non-violent, but recent years have seen violent protests as well, with a particular spike in 2007–08 due to riots over food prices; these protests are less well covered in international news. Compounding recent years of unrest, in which hot spots of civil war and armed conflict have also continued, there has been an increasing failure of existing political arrangements at the local, national and global levels to address grievances raised by protesters in a peaceful, just and orderly way. It is therefore of the utmost importance to understand what is driving recent protests, and in particular to do so on a global level.

This was the contention behind research contributing to “World Protests 2006-2013”1, which queried over 500 local and international news sources available on the Internet to analyse 843 protest events (both non-violent and violent, organized and spontaneous), occurring between January 2006 and July 2013 in 84 countries covering over 90% of world population. Researchers looked for evidence of main grievances and demands, who is protesting, what methods they use, who their opponents or targets are and what results from protests, including achievements and repression. The objective of the study was to document and characterize manifestations of protest from just before the onset of the recent world economic crisis to the present, to examine protest trends globally, regionally and according to country income levels, and to present the main grievances and demands of protesters in order to better understand the drivers of social unrest. The objective of the present article is to ask what light the findings of this study may shed upon one of the existential questions for human rights as posed by the editors of this 10th Anniversary issue of SUR: Is human rights (still) an effective language for producing social change?

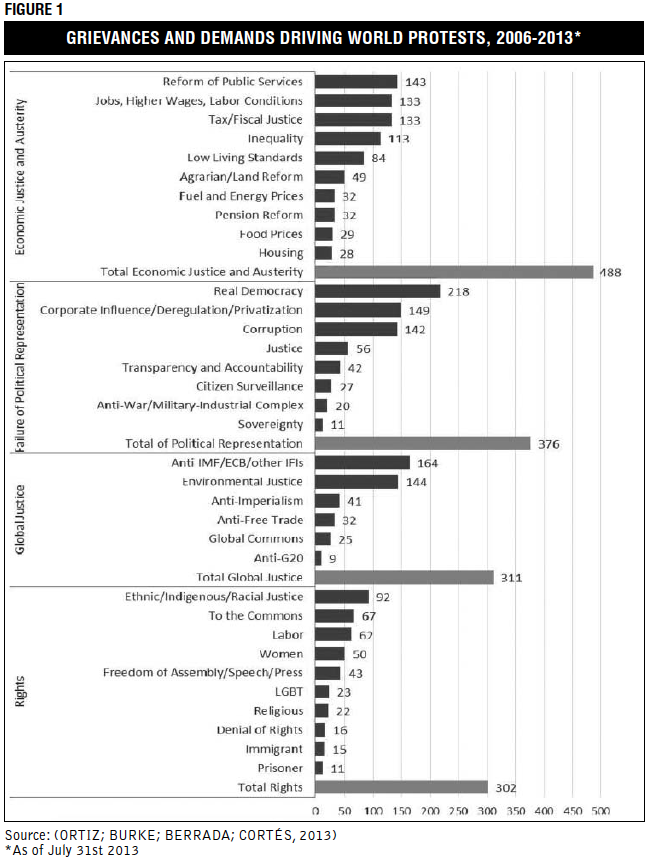

“World Protests 2006-2013” finds that the trend of outrage and discontent expressed in protests may be increasing worldwide. The leading cause of all protests is a cluster of grievances related to economic justice and against austerity policies that includes demands to reform public services and pensions; to create good jobs and better labour conditions; make tax collection and fiscal spending progressive; reduce or eliminate inequality; alleviate low-living standards; enact land reform; and ensure affordable food, energy and housing. Although broad demands for economic justice are numerous and widespread, the single demand that exceeds all others is found in a cluster of grievances pointing to a failure of political representation. It points to the very issue that prevents progress toward economic justice: a lack of real democracy (See Figure 1 for detailed list of grievances and demands found in the study).

As the key grievance in a widespread crisis of political systems, the demand for real democracy is counter-posed by many protesters to formal, representative democracy, which is increasingly faulted around the world for serving elites and private interests. The study found demands not just for better governance and wider representation, but also for universal direct participation and a society in which democratic principles—liberty, equality, justice and solidarity—are found not only in the laws and institutions but in everyday life (ERREJÓN, 2013; HARDT; NEGRI, 2004; RANCIÈRE, 2006). This demand comes from protesters in a variety of political systems, and protest patterns indicate that not only authoritarian governments, but also representative democracies, both old and new, are failing to hear and respond to the needs of a majority of citizens.

Grievances expressed as rights-based by protesters are one of the main groups identified in the study, but they are significantly fewer in number than those related to economic justice. Rights-based grievances and demands are also behind fewer protests than grievances related to failure of political representation or global justice. In the study, rights-based grievances are identified for human rights, civil and political rights such as freedom of assembly, speech and the press, and also for the social and cultural rights of ethnic groups, immigrant groups, indigenous, LGBT, prisoners, racial, religious and women’s groups (including protests for the revocation of existing rights). The study also notes some protests for rights that are both economic and civil/political, namely labour rights and the right to the Commons (digital, land, cultural, atmospheric). However, the economic justice demands that have dominated world protests since 2006 have not formulated themselves primarily in the language of rights or sought their realization primarily through national legislation of international norms, according to the findings of the study. Why might this be? Both a realpolitik examination of the powers and interests on both sides and a critical examination of the framing of economic rights, as compared to civil and political rights, offer some insight.

With regard to the realpolitik issue of power dynamics, the study finds that middle-class protesters of all ages, from students to retired pensioners, are increasingly joining activists from various movements. Not only in sanctioned marches and rallies, but in a new framework of protest that includes acts with greater potential consequences, including civil disobedience and direct actions such as road blockages, occupations of city streets and squares, and mass educational events and “happenings” to raise awareness about issues like debt, fair taxation for public services and inequality. The impact of people’s feeling about inequalities should not be underestimated in understanding what has driven many protests, particularly of the middle classes, in recent years. Even in a country which has seen policy-driven success in combating high inequality, such as Brazil, it has not proven enough to satisfy people’s demands, as seen during the summer of 2013 with the evolution of protests from localized demands for affordable public transportation to national demands for sweeping changes in social protection, distribution of wealth and government corruption.

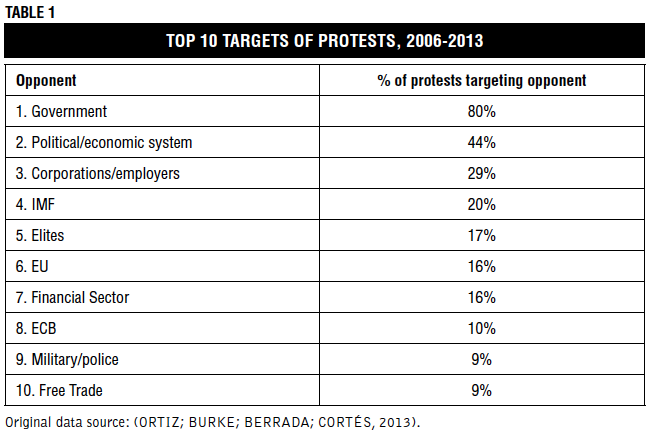

The other side of the power dynamic concerns the opponents of these protesters (Table 1 “Top 10 Targets”). The study finds, not surprisingly, that the target of most protests is the national government in the country where the protest occurs.2 Many protests also explicitly denounce the international political and economic system, the influence of corporations and the privilege of elites, including the financial sector. A large number of protests against austerity implicate the International Monetary Fund and European Central Bank, which are widely perceived as the chief architects and advocates of austerity. The challenge faced by protesters, concisely captured by Table 1, is achieving not just social change, but social justice. And doing it against the interests of a powerful nexus of poorly-representative governments and captured international financial institutions dominated by private corporate and financial elites, all of which are complicit in upholding an economic system that produces and reproduces inequality (of great concern to the middle classes) and privation (of ongoing concern to the world’s poorest). The repression experienced by protesters seeking economic justice offers further insight into the challenges they face and therefore the modes and methods of protest they have adopted. Not only riots, but more than half of all protests, experience some sort of repression in terms of arrests, injuries or deaths at the hands of authorities, or subsequent surveillance of suspected protesters and groups–surveillance that is carried out by both governments and private corporations.

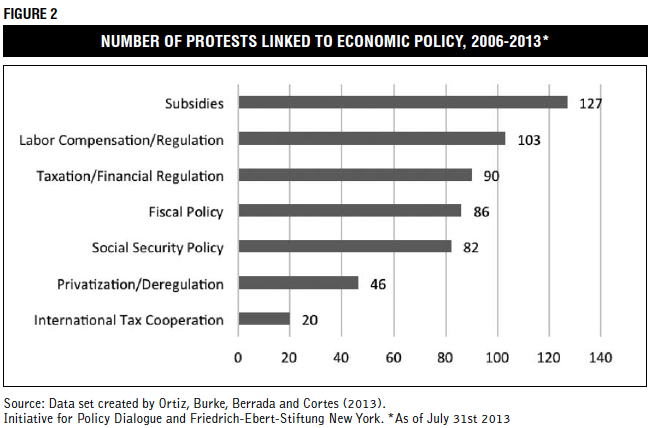

This state of affairs has been long in the making. Falling wages and shrinking pensions led to decades of rising inequalities and decreasing opportunities for decent work and full engagement in society, especially for youth, which has paved the way for the joining of middle class protesters with unemployed and precarious workers over this period. Of the protests linked to economic policy—either arising in response to a policy implementation or law or demanding policy changes—the greatest number are in relation to subsidies, typically a threat to remove a subsidy for fuel or food (Figure 2). A great number also relate to labor compensation and regulation of safety in the workplace, taxes and financial regulation, and fiscal and social security policies. A smaller number pertain to attempts at non-financial regulation and international tax cooperation. These protests are largely a response to the unravelling of the social contract that formerly bound the world’s middle classes more tightly to the policies of elites, including remnants of the welfare state. This unravelling contributes to a mounting failure of existing political arrangements at the local, national and global levels to deal with problems and protests peacefully and justly. The world’s people are roiled by economic needs that go unaddressed because they are, in ever greater numbers, shut out of the political processes in which decisions about the economy are made. Furthermore, they are shut out by the very elites who benefit directly from those decisions.

Can human rights norms and agreements be an effective weapon against such an adversary when its economic interests are at stake? Inequality, to a degree world protests indicate is unacceptable, is this adversary’s stated intention. This adversary counters all objections with imperatives: to prioritize growth and deregulation, low debt-to-GDP ratios, the rights of creditors and the privileged role owed to private interests in the economy and government. Could it be that the success of the Occupy and Indignants movements in changing the discourse around inequality lies in their resistance to formulating demands as a list of policies to be put to such authorities?

This was philosopher Judith Butler’s contention in a 2012 essay entitled, “So What Are the Demands?”, referring to the question repeatedly directed to the Occupy movement, which resisted giving a straight answer. Butler points out that even the most comprehensive list of demands—including for example, jobs for all, an end to foreclosures and forgiveness of student debt and so on—cannot but fail to express the movement’s ultimate ambition to resist inequality. This is so, she argues, because such a list can never communicate how those demands are related, and an end to inequality cannot be seen as simply one demand among many, but as the overarching frame. The problem requires instead a unifying and systemic approach (BUTLER, 2012).

Ironically, in spite of the principle that all human rights are indivisible and interdependent, the human rights field lacks a unified approach to economic, social and cultural rights, on the one hand, and civil and political rights, on the other. Progress in civil and political rights, the so-called “first-generation” human rights, such as the right to assembly, speech and religion, is largely based upon monitoring the relatively unambiguous presence or absence of negative outcomes (e.g. incidences of wrongful incarceration or censorship), whereas progress in economic, social and cultural rights, the “second-generation” of human rights, monitors their progressive realization over time (United Nations, 2012). In the case of economic rights, this is done via economic indicators that many protesters would find inaccessible because of their technical nature.

Excellent work has been done by a number of economists to rethink macroeconomics from a human rights perspective, including the model audits of US and Mexican economic policies conducted by Radhika Balakrishnan, Diane Elson and Raj Patel in 2009 for compliance with human rights obligations (BALAKRISHNAN; ELSON; PATEL, 2009), and the Outcomes, Policy Efforts and Resources to make an overall Assessment (OPERA) Framework developed in 2012 by the Center for Economic and Social Rights and their partners to create an overarching way for advocates and activists to build a well-evidenced argument about a state’s level of compliance (CORKERY; WAY; WISNIEWSKI, 2012). Despite this work, doubts remain about the usefulness of using human rights to fight economic injustice precisely because these are legal and policy-based goals that require responsive democracies with meaningful citizen participation, which is the very problem blocking progress toward more equitable economic systems. Perhaps this is why these path-breaking human rights economists are also modest in their goals, aiming less for radical change than to “move economic policy in a better direction by identifying which policies are at least likely to be inconsistent with human rights obligations” (BALAKRISHNAN; ELSON; PATEL, 2009). While their work remains an excellent guide for economic policy in real democracies, as a tool for the kind of system change that would actually fight further inequality, its value is sharply limited by political will.

The findings of the “World Protests 2006-2013” research and other efforts to map and understand the components of global protest—who is protesting and where, against which entities and with which methods, enduring what sort of repression and with what end results—should be of keen interest to those in the human rights field. They show that many protests that have shaken the world in recent years have framed their grievances as rights-based, but that the majority of protests, and those aiming specifically at changing the economic system—in particular its production and reproduction of inequality—have not pursued their aims in terms of rights, but instead in terms of economic justice and the need for real democracy. In conclusion, it is hoped that far-reaching and strategic thinkers within these protest movements, particularly those with the capacity to strategize on both a national and international level, will realize nonetheless that the advancement of human rights is necessary (if not sufficient) for the ultimate attainment of their goals.

1. September 2013 working paper by Isabel Ortiz, Director of Global Social Justice Program at Initiative for Policy Dialogue (IPD), Columbia University; Sara Burke, Senior Policy Analyst at Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung New York (FES-NY); and research assistants Mohamed Berrada and Hernán Cortés, Ph.D. candidates in economics and international relations, respectively. Research was funded jointly by FES-NY and IPD. The paper can be downloaded at http://policydialogue.org/files/publications/World_Protests_2006-2013-Complete_and_Final_4282014.pdf. Last accessed on: 15 Aug. 2014.

2. Note: many protests have more than one target.

Bibliography and other sources

BALAKRISHNAN, Radhika; ELSON, Diane; PATEL, Raj. 2009. Rethinking Macro Economic Strategies from a Human Rights Perspective. US Human Rights Network.

BUTLER, Judith. 2012. So, What Are the Demands?. Tidal: Occupy Theory, Occupy Strategy. March. Available at: https://docs.google.com/file/d/0B8k8g5Bb3BxdbTNjZVJGa1NTXy1pTk4ycE1vTkswQQ/edit?pli=1. Last accessed on: 15 Aug. 2014.

CORKERY, Allison; WAY, Sally-Anne; WISNIEWSKI O., Victoria. 2012. The Opera Framework: Assessing compliance with the obligation to fulfill economic, social and cultural rights. Center for Economic and Social Rights, Brooklyn, USA.

ERREJÓN G., Íñigo. 2013. The People United Will Never Be Defeated: The M15 movement and the political crisis in Spain. In: PUSCHRA W.; BURKE, S. (Orgs.). The Future We the People Need: Voices from New Social Movements in North Africa, Middle East, Europe & North America. New York: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. Available at: http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/iez/global/09610-20130215.pdf. Last accessed on: 15 Aug. 2014.

HARDT, Michael; NEGRI, Antonio. 2004. Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire. New York: Penguin Books.

RANCIÈRE, Jacques. 2006. Hatred of Democracy. Translation: Corcoran, Steve. 2006. London: Verso.

UNITED NATIONS. 2012. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Human Rights Indicators: Measurement and Implementation. UN Doc. HR/PUB/12/5/. Available at: http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/Human_rights_indicators_en.pdf. Last accessed on: 15 Aug. 2014.

ORTIZ, Isabel; BURKE, Sara; BERRADA, Mohamed; CORTÉS, Hernán. 2013. World Protest 2006-2013. IPD/FES Working Paper, New York. September. Available at: http://www.fes-globalization.org/new_york/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/World-Protests-2006-2013-Complete-and-Final.pdf. Last accessed in: Jul. 2014.