Advocacy Forum's Experiences in Prevention of Torture in Nepal

The present article reconstructs Advocacy Forum’s trajectory in combating torture in Nepal as an example of the human rights language’s capability to produce social change. As the article shows, Advocacy Forum’s strategy, called “Integrated Intervention Strategy” (IIS) and developed during the conflict and in the post-conflict period, has been effective in reducing the practice of torture in Nepal. The organization’s approach is holistic, based on a three tier-intervention – local, national and international. Furthermore, in addition to promoting legislative change as well as filing writs of habeas corpus and torture compensation cases, AF’s strategy encompasses attitudinal and practical transformations as well as institutional reforms in order to promote change on the ground. Advocacy Forum, the article argues, believes that the strategy developed by the organization can be applied in other contexts as well, because of its holistic nature and effectiveness.

The question of whether human rights are an effective language for producing social change is a critical and contemporary one. The present article uses the experience of the Advocacy Forum (AF) in combating torture in Nepal as an example of the human rights language’s capability to produce social change. AF’s experience also provides significant evidence that, to uphold this capability, the human rights movement should determinedly seek for holistic ways of realising human rights, such as constructively engaging with stakeholders and struggling for attitudinal and practical changes as well as institutional reforms.

Advocacy Forum (AF), set up by a group of lawyers in 2001, has since then been championing prevention of torture and of other human rights violations in Nepal. Considering the problem of routine and widespread practice of torture in pre-trial detention facilities, it started paying systematic visits to government detention facilities and monitoring and documenting the status of the detainees. The findings of the detention visits were shared and discussed with the stakeholders of criminal justice system to seek out ways to end the practice of torture in detention and provide justice and redress to victims. Also, these findings were reported to various national and international human rights organisations and bodies to garner support for the torture prevention work in Nepal and make people aware of the extent of the problem.

Nepal lived a decade of armed conflict between 1996 and 2006, initiated by the ultra-left party known as the Communist Party of Nepal (CPNM). In this period, Nepal experienced extra-judicial killings, enforced disappearances, torture, sexual abuse, abduction, extortion etc. perpetrated by both sides of the conflict. The warring parties (the government and the Maoists) both used torture for various purposes. The conflict reached a peak in 2001, when the government declared state of emergency, branded the Maoists as terrorists, and introduced the Terrorist and Disruptive Activities Ordinance (TADO). The ordinance provided sweeping powers to security forces to keep suspected members of rebel groups under preventive detention for up to 6 months without judicial scrutiny.1 It was then that AF started its work. Though AF focuses on monitoring and documenting five categories of violations — torture, extra-judicial killings, enforced disappearances, sexual violence, use of children in armed forces —, this article focuses on AF experiences in dealing with the cases of torture.

Amid a situation where arbitrary arrests and detentions were considered normal, state of emergency was imposed, access to government detention facilities was almost impossible. Generally pre-trial detentions were closed for outside world in Nepal. Determined to prevent torture, ill-treatment and illegal detention and to put constitutional rights of detainees into practice, AF was able to negotiate the access to police detention centres, using the law.

Torture in Nepal has been used as a criminal investigation tool to coerce detainees into confessing the crime, to destroy the personality of individuals and to impose authority on the victims, among others. Historically, it has also been used as a form of punishment. Despite having signed international commitments for absolute prohibition of torture in its territory by ratifying international instruments such as the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment of Punishment (CAT), and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), Nepal’s domestic implementation of this promise has been either inchoate or poor. The domestic laws are not on a par with the international prohibitions of torture. This discrepancy is further aggravated by the non-existence of independent monitoring mechanisms in the realm of preventive detention and by the virtual lack of impartial investigations into allegations of torture. Moreover, the existing legal system in Nepal is inadequate to provide justice and reparation to the victims and hold the perpetrators accountable for torture and other human rights violations (Advocacy Forum; Redress, 2001). Although the 2007 Interim Constitution of Nepal2 establishes torture as a criminal offence and the Supreme Court of Nepal (NEPAL, Ghimire & Dahal v. the Government of Nepal, 2007) has issued directives to pass a legislation criminalising torture, no legislation has been passed that specifically recognizes torture as a criminal offense and provides legal framework to bring those perpetrators to justice. This culture of impunity and lack of an accountability system is severely affecting the rule of law, respect for human rights, sustainable peace and development and efforts to strengthen democracy.

Against this backdrop, AF is doing its best to reduce and prevent the practice of torture, illegal detention and ill-treatment in places of detention by developing an innovative strategy called “Integrated Intervention Strategy” that focuses on holistic action addressing various gaps and inadequacies that overtly or subtly contribute to the institutionalisation of torture. The present article discusses AF’s experience in combating torture in Nepal, by describing the evolution of the aforesaid strategy, the challenges AF encountered and how law and advocacy measures can be coordinated and strategically used to achieve concrete and positive results in reducing the practice of torture in detention.

As mentioned above, the experience of AF in combating torture during the conflict and in the post-conflict era led to a gradual development of a strategy, which has been named as “Integrated Intervention Strategy” (IIS). ISS is a pragmatic framework that is built upon and reinforced by the lessons learnt during regular interventions to prevent torture. It includes all possible means of sensitising and collaborating with allies and potential allies, as well as strategies to co-opt and neutralise adversarial stakeholders, guided by evidence-based advocacy. It focuses on documentation and advocacy, filing suits for medical intervention, legal challenges to illegal detention, and collecting evidence for wider policy reform.

The strategy is a synthesis of previously defined conceptual paradigms and best practices internationally employed to prevent torture, on the one hand, and direct first-hand experience of AF attorneys in their daily engagement with torture survivors and dealings with Nepal’s criminal justice system. AF’s experience has shown that influencing justice system stakeholders, through evidence-based advocacy and daily responsible participation in the justice system, is the basis for sustainable change. Legislative change without practical implementation is of little comfort to those suffering injustices within the Nepal criminal justice system, thus the need of an integrated approach that brings out necessary attitudinal and practical changes as well as institutional reforms.

The strategy is implemented in three levels – local, national and international. Implementation is basically guided by four principles: 1) indivisibility (all strategic interventions must be harmonised and implemented simultaneously); 2) prevention (torture prevention is key to all strategic interventions); 3) immediacy (rapid response and proactive action); 4) legitimacy (interventions are carried out within the parameters of existing national and international laws, keeping the consistency and accuracy of the information collected).

Since torture and ill-treatment usually occur in places of detention that are inaccessible to any form of public scrutiny, monitoring detention centres is an integral part of any strategy aimed at protecting persons who are deprived of their liberty. This monitoring must be more rigorous than occasional visits by independent bodies to places of detention, followed by reports and recommendations. Visits must be regular and unannounced. Based on the very idea that such visits are one of the most effective ways to prevent torture, AF has been visiting detention centres on a daily basis in the districts in which it operates. Currently, AF visits 57 detention centres in 20 different districts across the country, though the organization’s reach was limited during the conflict era. AF lawyers visit custody centres every day to observe the situation of detainees, interview them and document their cases. Moreover, AF has developed a detailed questionnaire to record important information on a person’s detention, to support and defend the individual’s case as well as to challenge any illegal practices by the authorities. However, as AF lawyers face serious limitations (such as lack of separate and confidential place for the interview, denial of access to some cells, only one third of the detention being monitored) the organization’s current data can only provide a glimpse into the full extent of the practice of torture and ill-treatment in places of detention in Nepal. The data, however, provides consistent and clear evidence as to its existence.

Furthermore, AF, recognizing the importance and positive consequences of transnational advocacy networks in fighting impunity, has been continuously seeking to establish effective working partnerships with the international and domestic human rights community. As detailed later below, AF has contributed to increased involvement with the UN treaty and charter-based mechanisms on Nepal, which has helped to reduce the practices of torture in detention facilities.

Political interference in policing practices by powerful individuals and groups means that the most socially, politically and economically weak members of society are most vulnerable to abuses, including torture and ill-treatment. As presented later below, one way AF has fought against it is by pressuring the UN in its peacekeeping operations,3 as well as the US in its training activities, to take into consideration the record of alleged perpetrators. Moreover, in line with AF’s experience that, unless represented by a strong legal aid service, the courts, public prosecutors and police frequently fail to adequately ensure that detainees’ rights are respected, the organisation provides legal assistance to all victims of torture wanting to claim compensation through the courts. It also helps victims to file petitions for medical examination and medico-legal documentation, or habeas corpus if the detention is illegal. By providing free legal aid, from prosecution to adjudication, to the detainees and torture victims who are unable to afford an attorney due to poverty, illiteracy and other disadvantages, AF finds victims to be more encouraged to fight for their rights.

Past experiences of AF have shown that health professionals also take part in torture either by act or by omission, falsifying medical reports of failing to give appropriate treatment or medical report. As the Nepalese courts give greater weight to medical evidence, it is crucial to have proper medical examination and medical documents in allegations of torture or ill-treatment. While increasingly torture is carried out without leaving signs or with signs resolving within days, leaving no permanent traces, experienced doctors can nevertheless evaluate testimony, accounts of post-trauma symptoms and physical and mental sequelae and draw conclusions from these. It is vital that health professionals are able to promptly and impartially document and assess injuries. In some instances, medical health professionals are unable to do this due to fear, threats and intimidation by law enforcement officials. In other cases, doctors might have a vested interest in hiding evidence of torture and ill-treatment. Medical officers who carry out examinations of detainees are effectively subordinate to the police and subject to influence exerted by the police, especially within the precinct. Often police are present during medical examinations or post-mortems.

To address the problem of medical evidence and effective medico-legal documentation, AF has contributed to develop expertise at the national level in providing training for medico-legal professionals. It has been regularly providing training for doctors at the national and regional levels in line with the 1999 Istanbul Protocol (UNITED NATIONS, 2004), which provides detailed medical and legal guidelines for the assessment of individual complaints of torture and ill-treatment as well as for the reporting of such investigations to the judiciary and other bodies.

Moreover, AF has felt the need to constructively engage with stakeholders of criminal justice system such as police, public prosecutors, judges and defence lawyers. AF’s experience shows that the practice of torture in custody can be reduced if the actors such as the courts, prosecutors and defence lawyers start scrutinizing the treatment of detainees in places of detention. Capacity-building, training and technical support to relevant stakeholders is crucial to sensitise them. By organising a regular stakeholders’ forum, AF provides opportunities for these to discuss the challenges, and to find ways in a collective manner to address them.

In addition, AF believes that sustained advocacy initiatives around key laws and regulations relating to torture can result in tangible changes in law and practices. The relevant laws and policies need to be reviewed and the organisation intends to persistently advocate for amendments that ensure that the legislation complies with international human rights standards. For the purpose of advocacy and lobbying, it is of utmost importance to work in tandem with local media.

Advocacy Forum (AF) has seen encouraging results in preventing torture in Nepal with the implementation of the above strategy. At the local level, there are clear indicators that the existing laws are being implemented and there have been promising results in their compliance by stakeholders within the criminal justice system.

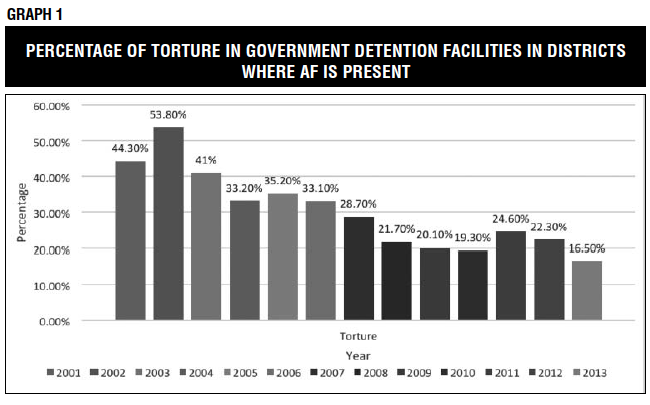

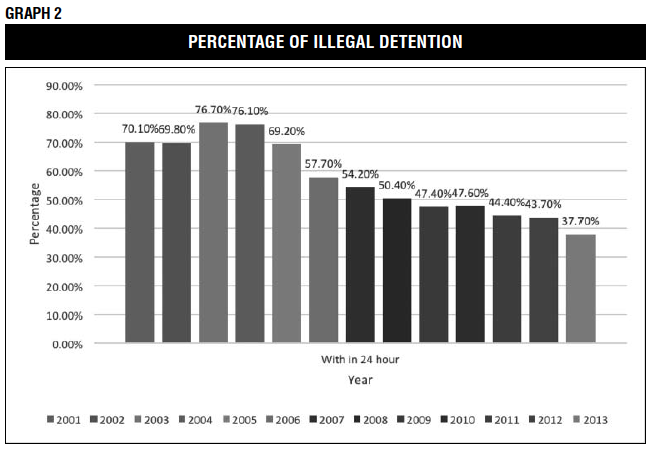

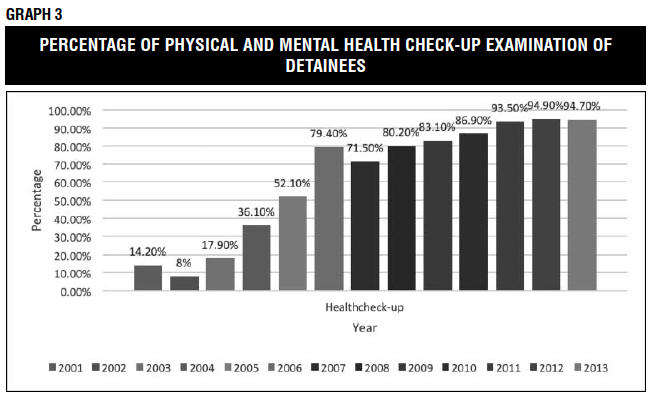

AF efforts have contributed significantly to reduce the frequency of torture and ill-treatment in government detention facilities. According to Advocacy Forum (2004), in the last 13 years, torture was reduced from 44.5 % (2001) to 16.7 % (2013) in government detention facilities in districts where AF is present (Graph 1). In 13 years, AF has visited 34,421 detainees. There have also been clear improvements in some crucial trends, such as illegal detention (Graph 2) and physical and mental check-up examination of detainees (Graph 3), which have contributed to a gradual reduction of torture and ill-treatment.

In addition, stakeholders in the criminal justice system are more sensitised about their legal obligations, which is reflected in their everyday work. During consultations, they have come forward, chaired the proceedings and even presented papers discussing different ideas to prevent torture. They have also asked AF lawyers for materials and other deliverables relating to international practices on prevention of torture. Our pressure to include human rights in general and prohibition of torture in particular as part of the curriculum in the training of the different actors in the criminal judicial system has led to the inclusion, in the training courses for judges provided by the National Judicial Academy, of issues such as the international standards against torture and the role of judges in the prevention of torture. This has resulted in judges not allowing hearings of criminal cases in the absence of defence lawyers, not extending the remand of detainees if medical reports are not incorporated and so on.

A general consensus on the need to pass comprehensive legislation criminalising torture has been built up, and the government has unveiled a draft bill in this regard. Engagement with local media and awareness-raising efforts (including placing billboards in the premises of the police stations outlining the rights of detainees) also have had positive implications in sensitising both police and civilians about detainees’ rights. The police have started to feel the pressure and to realise that they are not above the law and can be held responsible for the crime of torture they commit.

One of the outstanding transformations brought by AF efforts at the national level is the successful challenge of unconstitutional legal provisions that granted judicial powers to quasi-judicial authorities, including the Chief District Officer (CDO). On September 22, 2011 the Supreme Court issued a directive in order to review the quasi-judicial power granted to the CDO by various laws including the Public Security Act 1970, Arms and Ammunition Act 1962, and many more acts that gave CDO immense power; under such laws, the CDO was authorized to hear criminal cases. Challenging this jurisdiction of the CDO, Advocacy Forum (AF) had filed a writ on December 31st, 2009. In its ruling, the special Bench issued an order to review the provision and also issued a mandamus order for its immediate implementation. We had challenged the jurisdiction of CDO for sentencing people without a fair trial. We were concerned with the immense power vested in administrative authorities like the CDO, who could sentence a convicted detainee to up to seven years of imprisonment in certain cases, while a judicial authority gives punishments of up to six months of imprisonment in petty theft cases. This is in clear violation of right to equality of the accused. Furthermore, the CDOs do not possess theoretical or practical knowledge of the law, yet they were arbiters of justice.

After hearing AF’s arguments, the Apex Court found that granting powers to the CDOs had indeed violated the right to fair trial. The Court, however, refrained from declaring such provisions unconstitutional as requested by AF, stating that it would create a legal vacuum in the absence of other alternative bodies to undertake the said jurisdiction. In its directives the SC has ordered the government to form a research committee comprising legal and administrative experts to amend the existing laws providing the aforesaid power, and submit its report within six months. Following the order of the Supreme Court, the government of Nepal has initiated its task. It has formed a committee under the Office of the Prime Minister and has held consultation meetings for reviewing the powers of the CDO in 2012. This has resulted in the proposal of the government to amend a number of pieces of legislation and to provide three months of intensive legal training to administrative authorities, including the CDO.

AF also took the initiative to draft model anti-torture laws, leading a coalition of a number of civil society organisations. This draft was prepared after a series of reviews and consultations with victims, as well as national and international experts; the model legislation was made public on June 26, 2009, along with a report on torture titled “Criminalize Torture” (Advocacy Forum, 2009). Besides, this initiative has played a significant role in triggering a debate on the urgent need to adopt anti-torture legislation and other legislation on transitional justice mechanisms. The annual analysis of the information gathered from detention centres and its presentation provides basic knowledge on the issue of torture in Nepal.

Involvement with the UN treaty and charter-based mechanisms has increased in Nepal. Even after a decade of ratification of the first Optional Protocol to the ICCPR, there was no skill and know-how to bring communications before the Human Rights Committee. AF has therefore been assisting torture survivors to submit individual communications to the United Nations Human Rights Committee (UNHRC).4 Furthermore, AF has played a significant role in the recent confidential inquiry of the CAT Committee (UNITED NATIONS, 2012); it makes regular submissions to the CAT Committee5 and the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture.6 Also, AF has been successful in lobbying the diplomatic missions for implementing visa vetting – in which the host country denies giving visa to perpetrators of human rights violations (including torture) who intend to attend training, conferences, meetings or for personal visits (Advocacy Forum; Human Rights Watch, 2010, p. 10). Likewise, AF has been able to repatriate Nepali security officers implicated in human rights abuses from the UN Peacekeeping Mission. Leveraged by such international interventions, AF’s initiative has been able to lay ground for and open new possibilities in reducing the practice of torture in detention facilities.

AF has faced numerous hurdles and obstacles in its crusade against torture in Nepal. Both practical and institutional challenges have caused repeated interferences in its work. Foremost, the challenge AF is currently facing is the security of its lawyers/defenders. With the political transition still intact and continual deterioration of law and order situation amid the prevailing state of impunity, there is an emerging pattern of threats to lawyers. Regularly subjected to intimidation, AF lawyers are taking up cases of torture against police officers and advocating against impunity by building case dossiers against individual perpetrators. AF faced instances of infiltration in the organisation and stealing of case files, of a staff member being lured to spread dirt against leadership of the organisation and to make complains of irregularities in the organisation so the government might intimidate and harass it.

AF believes that detainees’ access to legal representation in the pre-trial phase is important to ensure fair trials and prevent human rights violations in detention, since police personnel may coerce detainees into signing doctored confessions by employing various methods of torture as well as threats of reprisal. Furthermore, the right to consult an attorney is also enshrined as a fundamental right in the Interim Constitution. But as AF lawyers provide legal aid to detainees from the pre-trial stage, they are more vulnerable to physical assaults and intimidation. AF constantly receives reports of our lawyers being denied access to detention centres. This happens mostly when cases of torture and illegal detentions are challenged. Regular attempts by police authorities to deny AF attorneys’ access to detention centres constitute a persisting problem. In other instances, AF lawyers and torture survivors have been threatened to refrain from registering the First Information Report (FIR) that demands criminal investigation in the cases of human rights violations and the writ of mandamuses that victims file in challenging lack of investigation in their cases. Also the victims withdraw cases because of intimidations and threats of reprisal.

Another challenge that AF has been facing is the overwhelming nature of the work performed by its staff – such as representing victims in courts, listening to their scary stories, being constantly involved in advocacy and lobbying and facing regular threats from state agents and other groups – and the detrimental impact that this has on their mental health. AF provides lawyers and other staff regular psychosocial counselling.

Political instability has also been an issue of concern. There is increasing frustration among victims and defenders alike, as impunity remains unfettered and unchallenged in relation to the crimes, including torture, committed during Nepal’s conflict. Despite concerted attempts by victims and civil society, the proposed transitional justice mechanisms have yet to materialize.

Most importantly, AF has been regularly harassed by the Social Welfare Council (SWC), a government body responsible for regulating non-governmental organisations. This Council has harassed AF either by not approving AF projects or by creating obstacles in the yearly renewal of the organisation’s legal status, which is a mandatory legal requirement for all NGOs in Nepal.

But the most serious challenge faced by AF is to keep up the momentum of its work on torture. To carry out such holistic work, AF needs to have adequate resources and receive continuous support, on a long-term, strategic basis. Vagaries in donor funding have negatively impacted AF’s work. A project-based approach can sometimes cause harm, by losing the momentum in projects like the one on prevention of torture. As our efforts are intended to bring systemic changes, they will necessarily take years to produce concrete results.

The lack of understanding of the political nature of human rights work and the risks involved in it among some funding partners also create problems. When funding partners change their priorities, they often force NGOs to shift their priority too. Funding partners often forget that their funding is for addressing the human rights deficit in Nepal through us and that NGOs are drivers of change. Non-recognition of the years of experiences and knowledge of activism in this field and giving too much weight to ‘expert’ ‘consultants’ can undermine the sustained impact of the NGOs’ work. Funding partners also have to be mindful that dragging activists and movements into the bureaucratic framework that have been created in developed countries and trying to impose it on local organisations impact negatively on preventing torture and other human rights violations.

When AF started its work, the country was immersed in the maelstrom of conflict, and torture by the security forces was widespread. Though the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) had been established then, it lacked teeth and was practically and resource-wise not ready to deal with the overwhelming frequency of human rights violations. Other civil society organisations were busy reporting violations, but the issue of torture was left on the back burner. In such a scenario, AF took the responsibility of monitoring detention facilities to prevent torture. Overcoming the fear of being branded as rebels by the security forces for helping suspected Maoist terrorists, AF attorneys continued to challenge illegal detention and torture by filing writs of habeas corpus and torture compensation cases.

AF’s strategy, developed during the conflict and in the post-conflict period, played a significant role in reducing the practice of torture. Further, AF’s three tier-intervention – local, national and international – has widened the scope of human rights work in Nepal. AF believes that the strategy developed by the organisation can be applied in other contexts as well, due to the holistic nature of its interventions and to its effectiveness.

1. Section 9 of TADO read:

If there is reasonable ground for believing that any person has to be prevented from committing any acts that could result in terrorist and disruptive acts, the Security official may issue an order to detain such a person in any particular place for a period not exceeding ninety days.

If it appears to detain any person for a period of time in excess of the period referred to in sub-section (1), the Security Official may, with the approval of His Majesty’s Government, Ministry of Home Affairs, detain such person for another period of time not exceeding ninety days.

2. Article 27 of the 2007 Interim Constitution of Nepal provides:

Right against Torture: (1) No person who is detained during investigation, or for trial or for any other reason shall be subject to physical or mental torture, nor shall be given any cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment. (2) Any such an action pursuant to clause (1) shall be punishable by law, and any person so treated shall be compensated in a manner as determined by law.

3. Quantitatively, “Nepal is the sixth in rank among the highly contributing nations to UN peace missions in the world”, according to The Himalayan, 19 March 2013. Available at http://www.thehimalayantimes.com/fullNews.php?headline=Nepal+Police+in+UN+Peace+Keeping+Operations&NewsID=369951. Last accessed on: 25 July 2014.

4. Available at http://advocacyforum.org/hrc-cases/index.php. Last accessed on: June 2014.

5. Available at http://advocacyforum.org/publications/un-submissions.php. Last accessed on: June 2014.

6. Ibid.

Bibliography and other sources

ADVOCACY FORUM. 2009. Criminalize Torture. 26 June. Available at: http://advocacyforum.org/downloads/pdf/publications/criminalize-torture-june26-report-english-final.pdf. Last accessed on 28 May 2014.

________. 2014. Promising Development – Persistent Problems: Trends and Patterns in Torture in Nepal During 2013. June 2014. Available at: http://advocacyforum.org/downloads/pdf/publications/torture/promising-development-persistent-problems.pdf. Last accessed on: July 2014.

ADVOCACY FORUM; Human Rights Watch. 2010. Indifference to Duty: Impunity for Crimes Committed in Nepal. December, p. 10. Available at: http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/nepal1210webwcover.pdf. Last accessed on: 28 May 2014.

ADVOCACY FORUM; Redress;. 2001. Held to Account: Making the Law Work to Fight Impunity in Nepal. Available at: http://www.redress.org/downloads/Nepal%20Impunity%20Report%20-%20English.pdf. Last accessed on: 28 May 2014.

UNITED NATIONS. 2004. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Manual on Effective Investigation and Documentation of Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. Available at: http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/training8Rev1en.pdf. Last accessed on: 28 May 2014.

________. 2012. General Assembly. Report of the Committee Against Torture. UN Doc. A/67/44. Available at: http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=A%2f67%2f44&Lang=en. Last accessed on: 28 May 2014.

Jurisprudence

NEPAL. 2007. Supreme Court. Ghimire & Dahal v. the Government of Nepal, 17 December.