Interview with Mexican activists Gerardo Torres Pérez & María Luisa Aguilar on forced disappearances in the country and the case of the 43 students from Ayotzinapa

More than 26,000 people are – according to official data – missing in Mexico today. This number is 600 times greater than the 43 students from Ayotzinapa. This group of youths became the symbol of human rights violations after they were ambushed by security forces on 26 September 2014 and forcibly disappeared at the hands of state agents associated with organised crime. The circumstances of the crime have still not been entirely clarified, nor are their whereabouts known. For the government, the investigation was closed following the claim that the students had been incinerated in a rubbish dump in the municipality of Cocula.

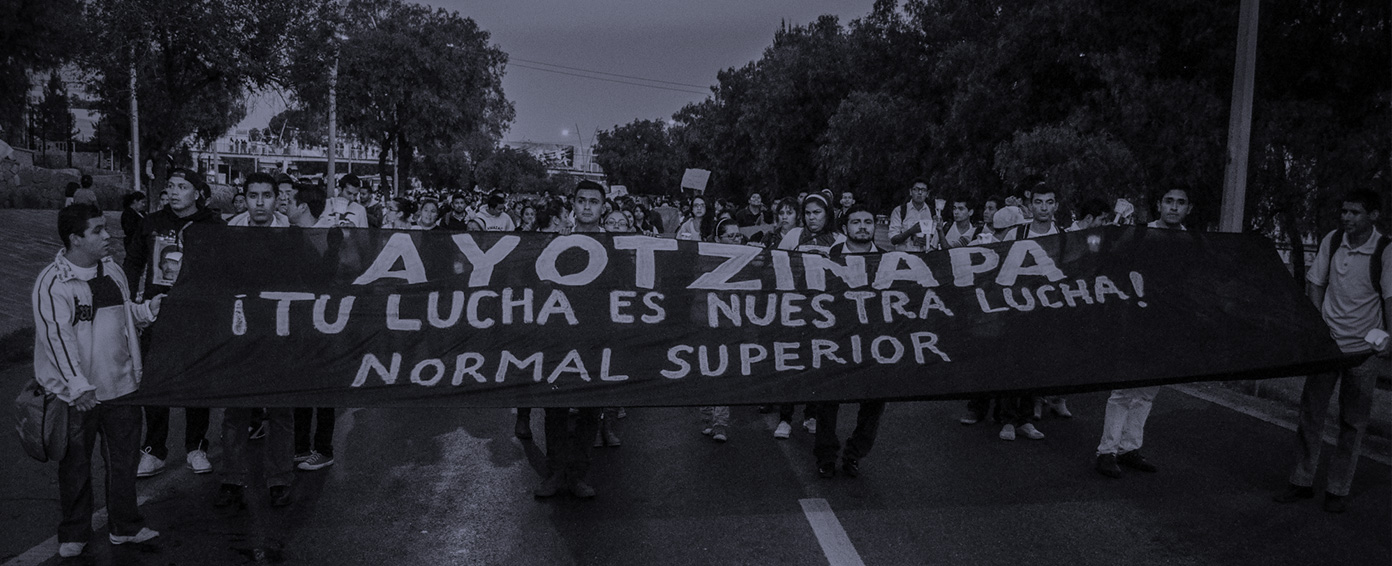

The disappearance of the young students from a rural teacher training school in the state of Guerrero, in south-west Mexico immediately triggered massive solidarity campaigns all over the world. For months, a search for the students from the “Raúl Isidro Burgos” Rural Normal School in Ayotzinapa was conducted while relatives, press and citizens, shocked by the brutality of the crime, watched in distress. Thousands of people took to the streets in various protests to demand justice and to express solidarity. On social media, numerous posts that expressed outrage maintained the hope, for a long time, of one day finding the group alive.

But now, the public spotlight has been switched off and darkness has descended on not only the destiny of the 43 young students from Ayotzinapa, but also on the fate of thousands of other Mexicans like them, whose whereabouts are still unknown.

What appeared at first to be an isolated tragedy in a small municipality in the state of Guerrero slowly turned out to be the tip of the iceberg connecting the Mexican state to organised crime in a web of various interests, the full extent of which remains unknown. Throughout Mexico there is an increasing number of cases about people who vanished forever under a dark cloak of violence and silence. They are people who, contrary to the students from the small rural school, do not arouse the interest of international solidarity campaigns.

Gerardo Torres Pérez, 22, was a classmate of the 43 disappeared persons. His younger brother was with the group that was ambushed that night, but was able to escape. IIn 2011, three years prior to the Ayotzinapa tragedy, Gerardo explained how he was involved in a similar case. Police officers captured, tortured and forced him to shoot a firearm in an attempt to get him to produce evidence against himself. The police wanted to make the Mexican justice system believe that Gerardo had fired a weapon during a peaceful student protest, where state agents executed two of his colleagues.

With the support of local and international human rights organizations, stories such as Gerardo’s and the 43 missing students from state of Guerrero are beginning to surface. The activist and coordinator of the international area of the NGO Tlachinollan, María Luisa Aguilar, says she expects that the Ayotzinapa case “will be a turning point” in the disappearances in Mexico. She has closely followed the work of the group of forensic anthropologists from Argentina who, as independent experts of families, are helping to shed light on the case.

At the same time, Aguilar tries to make sure that the precautionary measures and recommendations made by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), are accepted by the Mexican state. One of these recommendations resulted in the appointment of an Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts. Since March this year it has prepared reports11. More information about the latest report released by GIEI, – dated June 29, 2015 – is available at: http://www.tlachinollan.org/comunicado-giei-ayotzinapa-avances-y-pendientes/ with recommendations for the state focusing on four fronts: the search process, research to determine criminal responsibility, attention to victims and public policies against forced disappearance.

Aguilar and Pérez were both in São Paulo in May 2015 to take part in the International Human Rights Colloquium organised by Conectas, in which more than 130 activists from 40 countries participated. During the meeting, Gerardo and María Luisa spoke with Sur Journal about the Ayotzinapa case, the overall situation of missing people in Mexico and the connection between state forces and organised crime.

Various efforts – from protests to international campaigns – are aiming to keep the cry of resistance of the victims of violence and forced disappearances in Mexico alive. Between March and June this year, a “caravan” of the 43 students’ mothers and fathers, along with other students, travelled across the US, Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay. Its goal was to expose the situation at the teacher training college, advance the investigation and to ask the people of South America not to forget the struggle in Ayotzinapa.

Conectas Human Rights • What has been done to clarify what happened to the 43 students from Ayotzinapa?

Gerardo Torres Pérez • From the time of the students’ disappearance on 26 September 2014 until now, we have not received a clear and satisfactory response from the Mexican authorities. What they did eventually was to conduct investigations and apprehend several people who, according to them, are members of organised crime. They made these people declare that our comrades were dead. However, according to the forensic specialists who went there to carry out investigations, our friends cannot be considered dead merely based on the declarations of some arrested individuals. We, as students of Ayotzinapa, continue to say that they have to give us back our comrades alive. It was the state that tore them from us and who took charge of their disappearance, and that is why we continue to defend the same position. They have to give us back our comrades.

Conectas • Who committed this crime?

G.T.P. • According to the statements that our friends have given several times, it was mainly the municipal police that detained the students and put all of them in the vehicles that transported them. We do not know where they were taken. Some police officers who were arrested said that they handed the students over to organised crime. In other words, they work together with organised crime. That is why we say that it was a joint effort between the state and organised crime. In Mexico, there is a very clear notion of how organised crime works. It simply does the state’s dirty work – it takes care of making people disappear, killing people, violating human rights, etc. Thus, by attributing violations to organised crime, the state itself remains free from all blame.

“Officially, there are more than 26,000 missing persons in Mexico. No one knows where they are and the state does not have the capacity to search to find them alive”

Conectas • How much of this have you experienced personally?

G.T.P. • I am a student from Ayotzinapa. I was not there when the events happened on 26 September, but my younger brother witnessed everything. Luckily, he escaped from the massacre unharmed.

Conectas • Have you had similar experiences with violence perpetrated by the State or organised crime?

G.T.P. • In 2011, there was another case of state repression in the college, in which two comrades were killed by state agents. Since then, no physical or intellectual perpetrator of the crime has been arrested. It is something that has gone unpunished. They tried accusing me, saying that I had killed my own friends. They forced me to fire a gun, took me away and tortured me, as they wanted to force a false declaration saying that I had shot them. They were not able to incriminate me this way, but I was a victim of acts like this one committed by the state.

“As long as there is no certainty on the youths’ whereabouts, the search must continue. And it must seek to find them alive”

Conectas • We are talking about specific cases, but these are far from being isolated incidents in Mexico, right?

María Luisa Aguilar • The Ayotzinapa case is very symbolic because it involves a large group of very active students who succeeded in drawing public attention both in Mexico and abroad. The students’ parents mobilised themselves and civil society accompanied the process, but this is not an isolated case. Situations like this, involving security forces and their connection with organised crime, are something that happen all over the country. Officially, there are more than 26,000 missing persons in Mexico. No one knows where they are and the state does not have the capacity to search to find them alive, nor to say if they are forced disappearances, disappearances committed by organised crime or if they are people who are simply not in their homes. Obviously, organisations register much higher and alarming numbers of missing persons. Within this context, there are also disappearances of immigrants from Central America. This whole situation is set in a context of poverty: the population of the state of Guerrero is very poor. This is also the state with the highest proportional homicide rate. There is also a lot of violence and militarisation.

Conectas • How do human rights organisations deal with a context as difficult as the one you describe?

M.L.A • The first step that organisations like ours, which are assisting the students in Guerrero, took was to talk with an Argentine team of forensic anthropologists, in coordination with other organisations operating in Mexico so that we could address the different levels of authorities involved. The Argentine team of experts came to help the families because more than three weeks after the incident, authorities tried to tell the families that they had found clandestine graves that contained their family members. What is more, due to the families’ lack of trust, we brought in this group of specialists to work together on different parts of the investigation. We also took the case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Precautionary measures were requested for the missing students and the students who were injured – one of them is still in a vegetative state, while another two are in recovery. The process relating to precautionary measures also requested that the state provide technical assistance, which led to the Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts being brought over. This is an independent group that is reviewing the investigation and proposing recommendations on what the state needs to do and what is not being done. The initial recommendation, made since day one, is that as long as there is no certainty on the youths’ whereabouts, the search must continue. And it must seek to find them alive. Furthermore, this group will make recommendations on the relations between the state and organised crime, criminal investigations and, in a broader framework, how the state can confront a crisis of disappearances such as the one that Mexico is currently facing.

Photo by Antonio Garamendi / CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Conectas Human Rights • In crises such as this one, the attention of the press and public opinion lasts for a certain amount of time and then fades away, while the local reality continues to be terrible. Now that many people have stopped talking about the case, what is life for you and your comrades like?

G.T.P. • It continues to be the same, the way it was before all of this began. Assassinations and other human rights violations are still occurring. The state has taken it upon itself not to provide security. Even with police presence, people continue to be assassinated left and right. Lifeless bodies appear at dawn. We are very worried because we are the main ones involved in this situation. We feel that we could be arrested or even disappear at any moment.

“It is a school that will never surrender. And that is precisely why the state wants it to disappear”

Conectas • Why is this violence directed at you? Is it politically motivated?

G.T.P. • Our school has always been our struggle. We always support peasants and the poor – people without resources. The simple fact of providing education to people who have scarce resources is what gives us our political awareness. The state is the one who takes care of ensuring that we are increasingly submissive, increasingly poor. That is why they want the school to disappear. Luckily, we have a lot of support from the people of Mexico because they see our school as an incubator of professors, teachers and activists; it is a school that will never surrender. And that is precisely why the state wants it to disappear.

Conectas • What do you hope to happen going forward?

M.L.A. • That the international community will stop seeing Mexico as a reformed and progressive country in the area of international human rights and grasps the scale of what is happening there. The international community should continue to demand accountability from Mexico. We also expect something from Mexican society. This case has created a lot of awareness. We saw this in the streets and the different protests that took place. We hope that this will help to bring changes within Mexico – a country that has been so strongly marked by impunity in relation to human rights issues.

• • •

Interview conducted in May 2015 by Conectas Human Rights. Luz González and Josefina Cicconetti, from Conectas, assisted with research.