Putting Theories of Change into Practice

Creating lasting and effective cultural, behavioral, individual, and societal change entails choices and decisions. Without proper understanding of what generates, inhibits, or disrupts change however we remain ill-equipped to support individuals, organizations, or societies in their developmental process. The Minnesota Method for Human Rights change proposes a series of steps and tools to help human rights practitioners develop focus and strategy. Based on academic and practical knowledge this method will help you better understand the issues and actors in your community of interest; develop strategic plans and continue to adapt those plans as circumstances change.

Creating lasting and effective cultural, behavioral, individual and societal change entails choices and decisions. Without proper understanding of what generates, inhibits or disrupts change, however, we remain ill-equipped to support individuals, organisations or societies in their developmental process. At present, we possess very few tools that can help human rights workers gain the type of multi-dimensional information required to devise a strategy for change which stands a good chance of success. The Minnesota Method for Human Rights Change (MMHRC) begins to fill this gap.

The academic study of human rights has gained momentum in recent decades. While recent literature exists on theories of human rights change, there is limited academic work on the role and work of human rights field work.11. For example, the research team found only two works that recognize the role played by human rights advisors, though without delving into in-depth analysis: Daniel Moeckli and Manfred Nowak, “The Deployment of Human Rights Field Operations: Policy, Politics and Practice,” in The Human Rights Field Operation: Law, Theory and Practice, ed. Michael O’Flaherty (Farnham: Ashgate, 2007): 87–104; and Michael O’Flaherty and George Ulrich, “The Professionalization of Human Rights Field Work,” Journal of Human Rights Practice 2, no. 1 (2010): 1-27.

While human rights workers may have the appropriate backgrounds and understand the challenging reality of facilitating human rights change, there are few methods or guides that can help them to determine where to focus their efforts to maximise their contribution to positive human rights change. Clearly human rights are interrelated and interdependent, but trying to facilitate change in all areas at once may be ineffective. Facilitating positive change requires the strategic use of limited resources. Human rights workers need to know what change they will invest in and the lay of the land in terms of how difficult or easy facilitating change will be. They must also have a clear analysis of the possible obstacles and allies in facilitating change and a plan on how to facilitate the needed change, which much include measures for evaluating and revising the plan if the change is not achieved or the contribution toward the change sought was not as expected. MMHRC helps the human rights field worker maximise their contribution to human rights change by helping them answer the above questions and develop a focus and strategy.

Facilitating human rights change is an extremely challenging and long process involving many moving parts. Often, when human rights workers come up with an idea or strategy to effect change, a turn of events obliges them to continue to learn and to re-evaluate their strategy. Human rights change can therefore be described as a process of strategic incrementalism. When assessing particular situations, they encounter a number of stumbling blocks to progress in most, or even all, areas of their work. Financial constraints, politicians’ short term in office and desire to show change in that timeframe and the potential ambivalence of the population towards certain issues render the realisation of human rights aspirations highly challenging.

The goal of MMHRC is to enable human rights workers to use their time as efficiently and effectively as possible. By helping human rights workers to align the priorities of their potential allies with the strategic priorities that they have identified, MMHRC can be used by any type of organisation wanting to facilitate human rights change.

Societies are complex and creating change within a society is even more complex. Understanding and employing tools that create change is essential. In this article, we briefly discuss power analysis and advocacy networks. These tools for change can be more deeply understood by reading the cited authors.

Understanding who holds power in a community will help human rights workers know how and where to target their efforts. They should conduct a power analysis to map, observe and listen to the existing institutional system in order to identify the spheres where change is already occurring. Once these spheres are identified, we can invest our efforts in encouraging and nurturing change. Given that the change we seek is complex and will therefore undergo a non-linear evolution, a multifaceted strategy is called for. This strategy will have to be regularly evaluated and modified.

We must take into consideration factors such as social norms, evolution of the State, legislation, political parties and the media, among others. Using the steps outlined in MMHRC, we can gain a clear understanding of the role each constantly evolving system plays relative to the change we seek. This is a daunting task, but achieving such insight will help define our strategy.22. Duncan Green, How Change Happens (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016): 29-30.

The questions we ask (and must keep asking) are:33. Ibid., 8.

As we begin to identify and understand the roles of power in the communities we are working in, we may identify already existing advocacy networks or alternatively, a lack of such networks. Advocacy networks are an important tool for human rights work and can assist in the launching of systematic and coordinated activism campaigns that engage numerous organisations across broad swathes of society. Keck and Sikkink note that a crucial function of these networks is the development of a mechanism by which smaller and more marginalised actors can strategically pool resources “to help create new issues and categories and to persuade, pressure” and, perhaps most importantly, “gain leverage over much more powerful organisations and governments.”44. Margaret Keck and Kathryn Sikkink, Activists Beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks in International Politics (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1998): 1.

Creating advocacy networks should be an integral part of human rights workers’ mission given that they can offset/remove many of the time and financial constraints which stifle human rights workers. These cross-sector networks have the advantage of bringing multiple perspectives offering a higher vantage point, a feature which should prompt human rights workers to develop such networks or explore existing ones. Such interconnected webs will help bridge prospective gaps between the human rights workers’ strategy and the actual situation on the ground, and enable human rights workers to gain access to politicians and business leaders to enlist their support for the intended change.

In sum, partnerships in advocacy networks can play an important role in addressing human rights issues and accelerate change. Moreover, they enable human rights workers to bring together different aspects of the system in order to understand what is feasible.

Human rights workers work in countries facing multiple ongoing violations. Instead of trying to proactively address all these at once, human rights workers should instead focus on a few strategically chosen violations or issues where they believe that a meaningful and lasting impact can be made. MMHRC recommends first disaggregating the various human rights violations committed in a country, then prioritising which should receive the most effort on the part of that specific human rights worker. This process of prioritising is designed to gain support, clarity and buy-in from the diverse stakeholders so as to further coordinate efforts and establish shared expectations and priorities.

Prioritising a select few areas does not necessarily mean focusing on violations whose solution is the most obvious one. A human rights worker’s choice of violations to concentrate on must also consider the areas deemed most crucial by local communities. Ignoring pervasive human right violations would damage their credibility and consequently reduce the chances of achieving a positive impact. MMHRC is designed to offer strategic pathways to facilitate human rights change.

While some human rights workers may find that MMHRC reflects what they are already doing, others may be reluctant to adopt it on the grounds that it would entail too much additional work. Compared to assessments carried out by international organisations such as the World Bank and UNDP and by UN political and development advisors, the proposed method requires little time and resources to implement, helps to create the networks and constituencies needed to facilitate change and therefore increases the effectiveness of human rights workers. We hope that MMHRC will become an integral part of the planning and reporting processes of human rights workers.

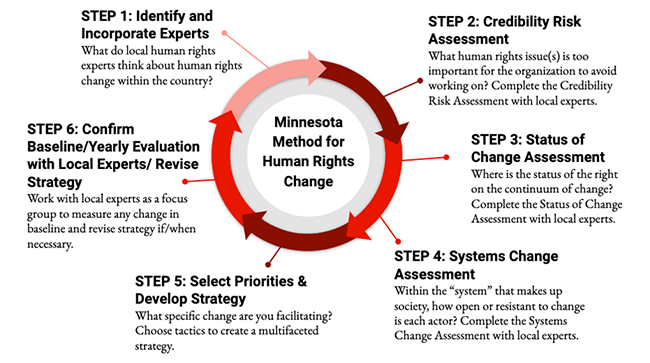

MMHRC is a cyclical six-step process. Each step is described in detail below.

Figure 1: Minnesota Method for Human Rights Change

The human rights worker should identify a group of five to ten experts from a varied range of local stakeholders with the objective of setting up an informal advisory council. Human rights experts are employed in ministries, national human rights institutions (NHRIs), non-governmental organisations (NGOs), religious institutions, the legal system, the media, academic institutions or other civil society organisations. In certain contexts, international experts could also be included, such as those at the UN, international financial institutions (IFIs), Member States, international NGOs and humanitarian organisations or academics. These experts have the knowledge, information and contacts that human rights workers may otherwise lack. It is therefore in the interest of human rights workers to be part of a large network of government, NGOs, religious institutions, academic institutions, think-tanks and any other relevant stakeholders. Local experts are an integral part of the process for setting priorities and assessing the pace of change. They may put human rights workers in touch with other engaged stakeholders or prospective partners and help them complete the remaining steps of MMHRC.

Ideally, human rights workers should be able to solicit local experts’ advice and input several times a year, or at least secure their commitment to completing the assessments once a year to provide the human rights worker with feedback on the impact of their actions.

Ask each expert to develop a list of the five to 10 human rights violations most present in their community. Ask the experts to be specific: for example, not just “access to quality education”, but “access to quality education of the rural and/or indigenous population.”

The human rights worker should then compile a list of the most pressing human rights violations based on the frequency with which the rights violation appears in the experts’ lists. For example, if there are 10 experts and all 10 identify a given violation, then this violation tops the list of compiled answers. This list should not be longer than the five to 10 human rights violations identified by the group as a whole.

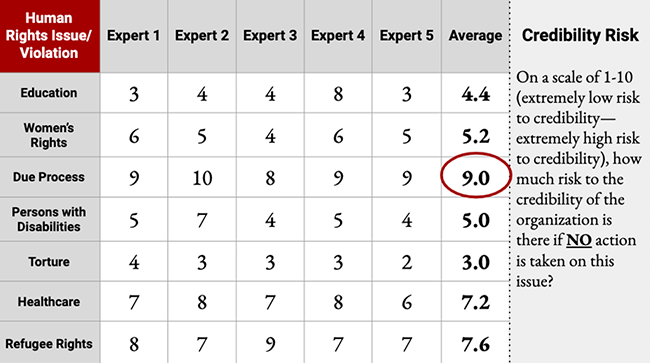

To conduct the Credibility Risk Assessment, the human rights worker, in collaboration with the previously established advisory council, should rate each human rights issue identified in Step 1 according to the level of risk to the organisation’s credibility in case it fails to actively address the issue. The human rights worker should work separately with each of the experts to complete a matrix for each of the rights identified.

Figure 2 provides a hypothetical assessment where seven human rights issues, taken from a hypothetical situation, are rated on a scale from 1 to 10, 1 being the lowest risk to organisational credibility.

Notice that in figure 2, due process rights has an average rating of 9, meaning there will be a wide credibility gap if the organisation fails to address this issue.

Figure 2: Credibility Assessment

As human rights workers promote common values embedded in the human rights treaties, the risk to the organisation’s credibility due to failure to address an issue that local experts deem important is real. Human rights workers must be aware that while picking only the low hanging fruit may be tempting, the main strengths of human rights law lie in its principles and that failing to uphold them will erode their credibility.

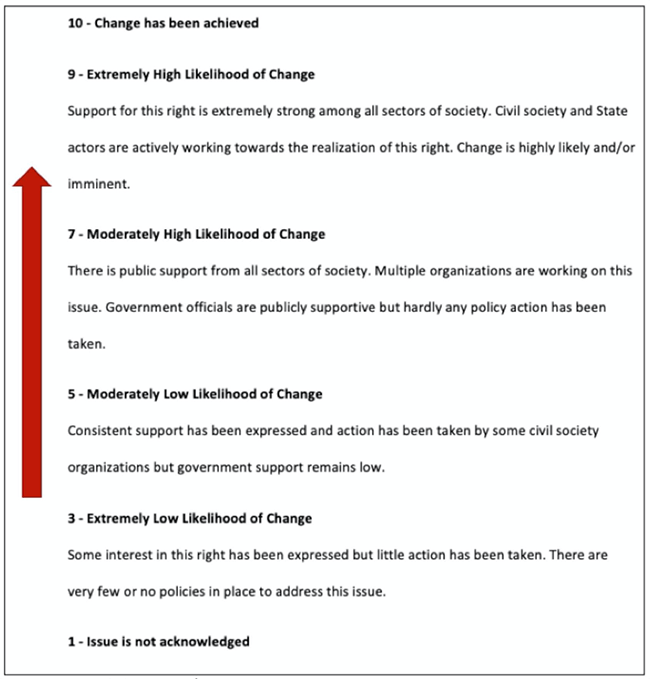

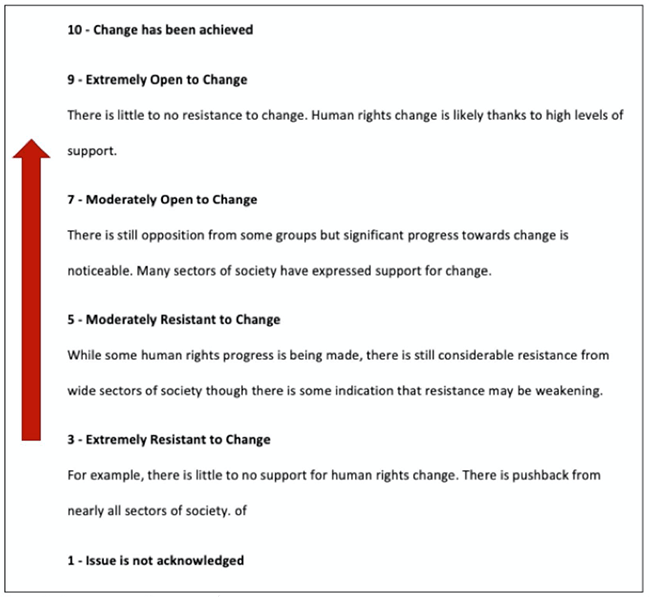

To conduct the Status of Change Assessment, the human rights worker should again work with the advisory council to rate each human rights issue and determine the position of the right on the continuum of change illustrated in figure 3 below. Again, the human rights worker should work with each of the experts individually to complete a matrix for each of the rights identified in Step 1.

Figure 3 provides guidance on how to determine the position of each human rights issue on the continuum of change using a scale of 1-10.

Figure 3: Status of Change scale

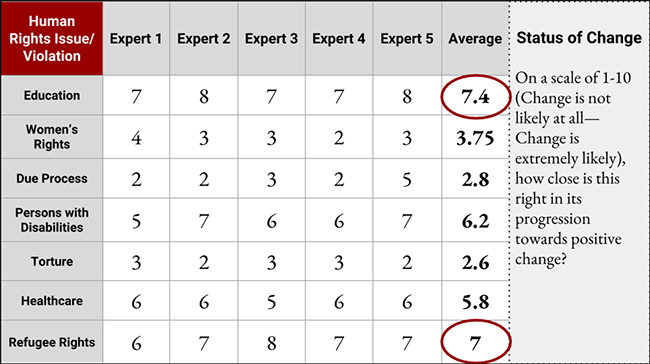

Once each expert has individually completed a status of change assessment, the human rights worker should create an aggregate table similar to the example seen in figure 4.

Figure 4: Status of Change Assessment

Notice that in figure 4, education received an average status of change rating of 7.4, indicating that this particular right is much closer to/more likely to be realised than the right to be free from torture, for example, which has an average rating of 2.6. These ratings suggest that a positive change towards the eradication of torture is unlikely or difficult to facilitate. Under this scenario, the right to education or refugee rights may be considered to be low hanging fruit, given the existence of significant momentum for positive change in these areas.

The reality of human rights change is extremely complex. While completing the Credibility Assessment and Status of Change Assessment, it is likely that the human rights worker may find that a particular right poses high risk to the credibility of the organisation if not addressed, but that achieving change in the level of respect for this right may be very difficult. We argue that human rights workers should consider working on these difficult-to-achieve changes if they pose a high risk to the credibility of their organisations, as avoiding the difficult issues can make it difficult to make inroads on other issues.

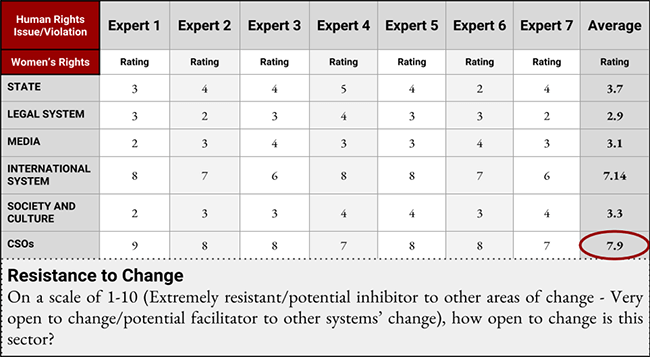

To conduct the Systems Change Assessment, human rights workers should continue working with local experts to determine whether various sectors of society would support the desired change. This assessment differs from the two previous ones insofar as the experts will be requested to analyse the role that relevant actors play relative to a specific right. Actors exerting influence over the change process may include the State, the legal system, the media, the international community, society and culture, civil society organisations, political parties, transnational corporations, activists and leaders. These actors will vary depending on the specific context of the community the human rights worker is working in.

Figure 5 illustrates a System Change Assessment based on a hypothetical study assessing women’s rights in a given location.

Figure 5: Systems Change Assessment55. Depending on the country context, human rights workers may wish to include additional entities or institutions in the Systems Change Assessment.

Note: Refer to Figure 6 (below) for guidance on how to determine where each entity is situated on a scale of 1-10 for openness.

Figure 6: Openness to Change scale

Using the scores from the above assessments and considering the priorities, available tools and resources of their organisations, human rights workers should identify a limited number of rights to prioritise.

Human rights violations are extremely complex and almost always wide-ranging in scope. This requires human rights workers to be specific when defining the themes related to the right they will be working on. The right to education, for instance, is a broad issue involving many stakeholders and might be narrowed down to one aspect such as, for example, classroom accessibility for learners with disabilities.66. “Strategy Toolkit,” New Tactics in Human Rights, The Center for Victims of Torture, 2014, accessed May 12, 2020, https://www.newtactics.org/toolkit/strategy-toolkit.

The “missing” link to change may be legislation and policies, lack of political will, weak or non-existent institutions or entrenched social norms that are resistant to change (though potentially, they could evolve and embrace change). Human rights workers must discern these missing components in order to devise a strategy. The missing elements may emerge at any time, for example, during discussions with the experts. Most often, knowledge of the challenge will emerge over time, necessitating further research related to how to foster change, along with further consultation with experts, desk review and engagement with organisations working on the same issue. MMHRC is designed to help human rights workers be as specific as possible about which aspect of the targeted rights will be addressed strategically within the community that they are working with. When developing a strategy, they should ask themselves the following:

Once goals are identified, human rights workers, in collaboration with relevant stakeholders, should select appropriate targets and tactics to create a multifaceted strategy to deliver the desired results.

Targets are the groups or individuals that can contribute to change, many of whom the human rights worker will have already contacted (see Step 1, local experts). These stakeholders, whose connections and expertise the human rights worker will leverage throughout the change process, are potential allies for building an effective plan of action and can play a pivotal role in helping human rights workers map out who is working for and against the priority issues identified. When thinking about targets, human rights workers should reflect on the following questions:

When setting targets, it is important to identify specific individuals within specific organisations. When considering who to target, human rights workers should ask themselves the following questions:77. “Map the Terrain,” New Tactics in Human Rights, The Center for Victims of Torture, n.d., accessed May 12, 2020, https://www.newtactics.org/sites/default/files/resources/Map%20the%20Terrain%20-%20Method%20Overview.pdf.

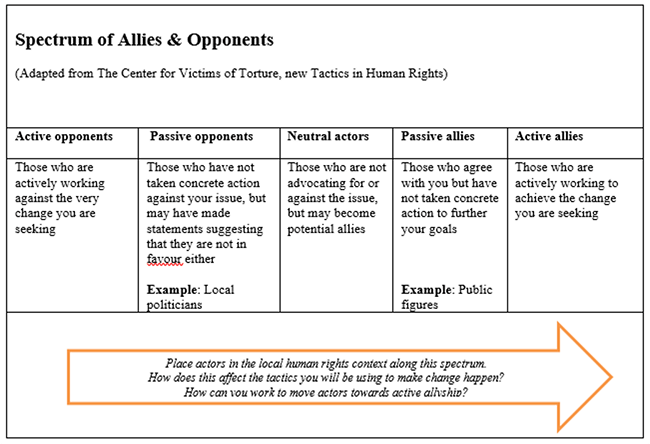

Using tools such as the Spectrum of Allies & Opponents, developed by the New Tactics programme at the Center for Victims of Torture, may prove useful in identifying potential targets88. “Map the Terrain: Identifying Allies & Opponents Using the Spectrum of Allies Tool,” New Tactics in Human Rights, The Center for Victims of Torture, n.d., accessed May 12, 2020, https://www.newtactics.org/sites/default/files/resources/Map%20the%20Terrain_Exercise_Identifying%20Allies%20%26%20Opponents.pdf. (see figure 7). The purpose of this tool99. Ibid. is to help advocates visualise who specifically is working to further their goals, who is actively working against the desired change and who is positioned in the middle of those two extremes. Ultimately, the aim is to have stakeholders move along the spectrum and become allies. For example, if a certain politician falls into the “passive allies” segment, the hope is that by the end of the advocacy efforts, he/she will have crossed to the “active allies” segment: after simply expressing support for the cause, he/she takes concrete steps towards the hoped-for progress. Having “passive opponents” move into the “neutral actor” segment, where their actions can no longer harm the cause, is also an effective tactic.

Figure 7: Spectrum of Allies

Tactics1010. “Map the Terrain,” New Tactics in Human Rights, The Center for Victims of Torture, n.d. are strategic actions taken in order to meet set goals. Most successful advocacy campaigns deploy multiple tactics including raising awareness, mobilising allies, seeking justice, reducing fear, offering incentives, changing mindsets, facilitating collaborations, building capacity, etc. As people and situations change, tactics should remain flexible.

While the ultimate goal is to achieve progress in the protection of human rights, it is crucial to determine immediate, mid-range and long-term steps that will help pave the way for change.

The three assessments above are useful tools not only because they can help human rights workers choose which issues to focus on, but also because they provide a “baseline” enabling human rights workers to return to the same group of local experts every year in order to gauge how much progress has been made, if any. The feedback they receive can also help them assess their annual strategy and revise it, if necessary.

As the human rights worker goes through this process, it is important to maintain communication with stakeholders and an orientation towards community engagement. If stakeholders and community members do not feel engaged in this process, change is unlikely. In addition, the human rights worker should work to maintain open lines of communication with other organisations who are working on similar issues. It should be remembered that one of MMHRC’s principal goals is to enable stakeholders to strategically align priorities and create common expectations.

MMHRC is a cyclical process designed to respond to shifts and obstacles encountered along the way. Strategies will regularly need to be reviewed based on new developments and an evolving understanding of a given situation. The process can be restarted at any time and be replicated for any issue.

With the weight of human rights law behind them, and provided that they have a strong network of connections and extensive human rights knowledge and choose the right tactics to accomplish their mission, human rights workers will find the task of bringing about human rights change, as daunting as it may be, more manageable.