By Renato Barreto

For Mônica Nador, art, life and emancipation are inseparable. The visual artist, whose earliest works date from the 1980s, studied Fine Arts at the Armando Alvares Penteado Foundation (FAAP) in São Paulo and has a masters from the School of Communication and Arts of the University of São Paulo (ECA/USP) for her work “Wall Paintings”. In 2003, Mônica founded the Jardim Miriam Art Club (JAMAC), located in the neighborhood of Jardim Miriam in southern São Paulo, a cultural center whose primary goal is to develop training processes that encourage encounters between art and life, aesthetics and politics, by hosting activities such as workshops, exhibitions, round table conversations and drop-in classes, always with a focus on diversity, civic awareness and the right to the city and to memory.

Addressing the right to culture as a human right, in this interview the artist discusses, among other topics, awareness and appreciation of each person’s culture and the importance of art in political and civic awareness. The images that illustrate the projects mentioned over the course of the interview are part of the gallery of artwork selected for this edition of Sur.

Sur Journal • Do you consider your occupation as an artist to be part of what is understood as defense of human rights? Based on this, what meaning do you assign culture these days as an artist?

Mônica Nador • I’ve always thought that everyone should work to improve society as a whole. I know that I have a somewhat religious mentality, even though I’m not religious, which is why I identified with a text I read once by Meister Eckhart,11. Eckhart von Hochheim, O.P. (Tambach, Thuringia, 1260 - Cologne, 1328), commonly known as Meister Eckhart, a German theologian, philosopher and mystic. who was a theologian from the Middle Ages, in which he states that knowledge should not be used for anything else but achieving a situation of equality for all humans and animals on the face of the Earth. This is what has value. We need to work for everyone, and not let anyone suffer. We should do as much as we can to alleviate people’s suffering on this planet.

When I was studying architecture, in 1974, it was the height of the dictatorship. We were advised to work on low-income housing, to see how these people live and work. But my school ended up being shut down and I was forced out too. So I ended up doing art. And in art education, we have a very conventional vision of culture – culture is separated from other activities, from society.

Even though I had a good reputation and people liked my work, I never felt right in that environment. That life really wasn’t for me, because you have to be extremely competitive. You have to go out and sell your work. You have to be forceful, and I’m just not at all like that, you know? In fact I’m quite the opposite.

I even thought about quitting. I nearly gave up making art at one point, about 10 years into my career when I was working the circuit. But after I started my Masters, I began to understand this concept of the circuit, and how it happens.

This opened my mind and I decided to make art in another way, the way I thought it should be made. That was a really great time because I did this project, Wall Paintings, which removed art from this extremely conventional, bourgeois vision that art is an adornment in your life, and never a structural axis of your life. I fought for this place, for me and for my art. I didn’t want my life to be that – an adornment in the life of a collector.

Having said that, the meaning of culture I work with these days is more connected to all other areas, of knowledge and of life, everyday life. Art is not at all separate from life. It’s not, like, “oh, art!”. I know things have changed a lot, but when I started working 40 years ago, it was all “oh, art!”, you know what I mean? Even in my case, ditching this concept took some time. It took a long time.

Sur • How did you come to decide to move to southern São Paulo and found the Jardim Miriam Art Club (JAMAC)?

M.N. • First of all, it had a lot to do with my project, which involved painting houses with the people who lived in them, with the designs done by them. And so the concept of shared authorship was born, because I offer an opportunity for these people to contribute and participate in making a work of art. Not only do they learn, but they also make a real contribution.

This came about by studying. In graduate school, I began to understand that what matters the most is choosing your audience. Choose your audience and see who you want to speak to. Myself, for example, because I wanted to speak to the excluded, so to speak, I decided to go to Jardim Miriam to be close to the people who could benefit from my work.

I didn’t want to do my work and then pose in exhibitions with photographs of my pieces. I could have done that – and I did for a while – but that isn’t what interested me. What I really wanted to do was to contaminate people with this life that we lead, and they have no idea what could happen.

That’s how I went looking for my audience. I am from a generation that was forbidden to make socially engaged art. It was considered a bit tacky. One thing I learned is that there is no point doing socially engaged art in a gallery, for example. The talk is always among our peers, and I wasn’t the least bit interested in that. What I really wanted to do was intervene in reality.

Sur • What changes and impacts did you observe in the territory from your work and the interaction with the local population, including residents, artists and activists from the region?

M.N. • Other than the fact that it’s very good for your health, that this work lifted people out of depression… Other than this, which I wasn’t really expecting, this work had an incredible effect on people’s mental health.

But irrespective of this, I’d say that I was lucky to have met Mauro [Mauro Castro, who collaborates with JAMAC since its foundation]. Mauro was a true activist. He was a metalworker for 30 years. Then, when the layoffs started in the early 1990s, he was one of the first to go because he was a nuisance, political, very articulate and a good speaker. He was never interested in a political career, but he plays a very important role in the community – he keeps everyone in line. He gets everyone to do various things.

But when I arrived at JAMAC, I said: “Look, I want to set up this cultural center, but I don’t want to do it just for me. If you don’t want it, I won’t come here and impose myself”. Then he said: “Actually, I have no idea what culture is for”. You see: he studied social sciences in the evening for 20 years and also had a degree in geography. He had studied a great deal. And yet, he didn’t understand my role there. I asked him: “So, what do you like doing?” And he said he liked having classes. So we set up a continuing education project. It was eight to ten years of hard work, bringing people to speak and teach. It was wonderful.

So, Mauro began to understand the role of culture, until he came up with the Rádio Poste radio project, which is entirely a part of JAMAC. Rádio Poste basically involved going down to Miriam Plaza once a month with a microphone and talking to people. He would talk about all sorts of things and people would go there to listen. To begin with it was funny, even drunks would be there. Now it’s more organized, but it’s okay for drunks to go. I think it’s great.

He would lay a sheet of fabric that I gave him on the ground and put some books on it. They still do that today. Then people can take these books, steal them, return them the following week… all for free. And so a network of people who do culture, people who do politics and education ended up being organized in the neighborhood.

Sur • Tell us a little about the Wall Paintings project and the involvement of the public who participate in JAMAC’s activities in the process of representing their life stories and other subjectivities.

M.N. • When I started, I wanted to make art for Brazil, you know? So, thinking of the language based on local needs. Using art as a tool and being a platform for social work based on this language. That was the work we did with Wall Paintings, which was to paint the houses of low-income people. Make the art with them. That was a very original idea when I started doing it.

It happened like this: I used to go to the favelas a lot to do this work. At the beginning I noticed something, out in Amazonas, the first time I went to paint houses. I went there, I wanted to paint a house and I asked people to draw things. There was a boy who lived in a house on the banks of the Purus River, 17 hours by boat from Manaus – they didn’t even have cars in that village, just one tiny business. That amazing sunset, that red sky, that beauty of the Amazon. And the boy drew the Nike symbol. I felt completely sad and frustrated.

I began to understand that, as I saw it, they had no self-love. The most colorful thing that happened there was television. All the houses were completely rustic, but they all had a damn antenna. Dirt poor, but with an antenna. I also started to realize something else: most of those people have their origin in the countryside, although some were forced to leave the urban centers. It’s the people who are driven out of the countryside who go live in the favelas. There, they just don’t know how to be urban. They don’t know what it is. For them, being urban means consuming.

So, I went there on a rescue mission, for them to rescue their original culture. I started to ask, and I still ask today: “Do you remember anything about your grandmother’s house? Do you remember something you liked to do when you were a child?”. And things start to flow.

Later, when I went to Gwangju, for an art biennale in Korea, I asked the participants to think about the first image that came to mind when they thought about Brazil. That’s the idea, but you can adjust it depending on the circumstances. I can adjust the subject of the question.

But, in principle, it was this: to recover people’s culture so they can learn to be a new type of urban. An urban that only they can be, because they just came from the countryside. And it was great because they came up with ox carts, for example, that kind of thing. Really lovely.

Sur • In the case of the Raising Flags project, carried out in partnership with the artist Bruno O., what was the purpose of remembering and portraying women of historical relevance in the defense of human rights in Latin America, whether alive or deceased?

M.N. • Raising Flags is a project22. “(...) The installation is an exercise in visibility and memory of those women and it aims to acknowledge presences excluded from a colonial grammar composed of supposedly neutral and universalizing images of the world, but which is exclusively linked to the construction of monuments that are white, male, cisgender, heterosexual and hegemonic.” “Mônica Nador”, 21st Contemporary Art Biennale Sesc_Videobrasil, 2019, accessed on July 31, 2020, http://bienalsescvideobrasil.org.br/artista/monica-nador. that we did, but the idea for it was much more Bruno’s [Bruno O., a visual artist and collaborator of JAMAC]. It’s this: we can’t let our memories get hollowed out and full of gaps. We need to keep reaffirming all these women. The purpose of remembering is this, to never forget that these people were assaulted, or are assaulted, all the time, and that these people are us.

As a result, I have taken a step further on this issue of human rights, because I included figures with more visibility, so to speak. Although I have also worked with the figure of Che Guevara. But the size was Bruno’s idea.33. Each flag was 6 meters high and 1.33 meters wide. They were displayed on the internal ramps of the Sesc 24 de Maio building in downtown São Paulo. He decided to work with women and we already have a lot of them there.44. Débora Silva Maria (activist and founder of the Mothers of May movement); Marielle Franco (sociologist and city councilor; murdered in 2018); Renata Carvalho (actress and transpologist, in her own words); Cláudia Celeste (actress and the first transvestite to act in a soap opera; died in 2018); Conceição Evaristo (writer); Carolina Maria de Jesus (writer, died in 1977); Zuca Fonseca (psychologist and collaborator of JAMAC); Margarida Alves (unionist); Maria da Penha (pharmacist and activist for women’s rights); Nise da Silveira (psychiatric doctor; died in 1999); Joênia Wapichana (indigenous lawyer and federal congresswoman); and Nilce de Souza Magalhães (activist of the Movement of People Affected by Dams; murdered in 2016).

Sur • You and JAMAC participated, in 2019, in the Somos Muit+s (We are Many) exhibition, at the Pinacoteca Museum in São Paulo, in partnership with the Extramuros educational project, which works with homeless people and the trans population. How important is it to engage and work together with other institutions, whether artists or cultural centers, both inside and outside Brazil?

M.N. • I think it’s very important, because we need to draw attention to the network of spaces available for this type of subject. I think it’s great that, in my case, I can take over the Pinacoteca Museum with that mass of homeless people, for example. I think it’s very important, because we don’t want people living on the streets anymore. It’s important for us to occupy these spaces. I think it’s great that I’m in these places because I put all this into it. It’s good to make this mark there. It’s all about giving visibility. Giving visibility to these institutions that are more on the sidelines – but I put “sidelines” in inverted commas.

And I don’t only work in the third world; I also work in third world enclaves within the first world. In the first project I did on the border between Mexico and the United States, I was working there with a community of maquiladora factory workers, directly with these people.55. Insite 2000, San Diego (United States) and Tijuana (Mexico). And now, in the work we are doing in Oslo, Norway,66. “Another Grammar for Oslo,” osloBIENNALEN, 2019, accessed on July 31, 2020, https://oslobiennalen.no/participant/monica-nador/. our intention is to work with immigrants and rescue memories. So, we strive towards people’s emancipation, by trying to promote this.

Sur • What challenges do you see for universal access to the right to culture and the right to the city, so there can be, in your own words, “spaces of liberty on every corner”?

M.N. • First of all, I went to the urban outskirts because I thought it didn’t exist there – that they needed much more than a cultural center. In fact, things have changed a lot now. The “spaces of liberty” in the urban outskirts are the Umbanda religious sites. They are different – not the sort that us whites from the city would recognize.

After all, the official culture exists, among other things, to defend white supremacy. But this is what I think: we are facing a hell of a setback now with Bolsonaro, we are really under threat. I firmly believe that a fight, an expenditure of energy in this cause is really worth it. I have done this my whole life. This is what it’s about: the right to culture is the right for you to be who you are. You don’t need to strive to be something else. It’s you being. That’s all.

Mauro, who was an activist in the health sector, started to distribute flyers that read: “We have to hold a meeting to discuss the hospital that we need here, and the cultural center”. So he then became a cultural activist. At one event we attended together, he said: “I want to tell you something: my cultural development took place in the Candomblé environment”. When he said that, I almost kissed his feet and I thought to myself: “mission accomplished”.

Interview conducted by Renato Barreto in July 2020.

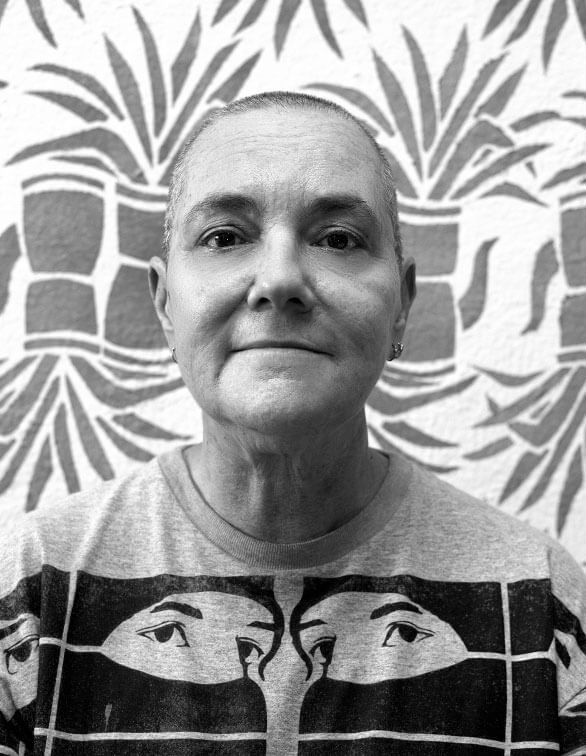

Mônica Nador and two of JAMAC’s creations, on the wall and t-shirt, made using the stencil technique. Credit: Gustavo Malheiros.