How mining activities in Afghanistan negatively impact local communities

Despite possessing a wealth of mineral resources, Afghanistan is one of the poorest countries in the world. Although the country has a relatively well-structured legal framework in relation to mining, rarely is it properly implemented. Consequently, the sector is plundered by corrupt politicians and local warlords. Here Javed Noorani provides an overview of the existing legal framework. He then offers three examples where this framework has failed to protect the local population from human rights abuses. Finally, he suggests how the situation might be improved including, for example, by revising existing legal provisions to include greater emphasis on anti-corruption measures and working to guarantee that community consultations are properly undertaken.

Afghanistan has some of the most complex and varied geology in the world. The country is home to lead, zinc, iron, chromium, tin-tungsten, mercury and uranium as well as several kinds of rare earth elements. The copper belt in Afghanistan stretches for 600 km.11. “Geology of Afghanistan,” British Geological Survey, accessed May 25, 2017, https://www.bgs.ac.uk/AfghanMinerals/geology.htm; “Ferrous metal,” BGS, accessed May 25, 2017, https://www.bgs.ac.uk/afghanMinerals/femetals.htm.22. “Other Metals,” BGS, accessed May 25, 2017, https://www.bgs.ac.uk/afghanMinerals/othermetals.htm. Among the 93 types of precious metals found in the country are gold, silver and platinum.33. “Geology of Afghanistan,” accessed May 25, 2017. Furthermore, Afghanistan also has several kinds of precious and semi-precious stones including emeralds, rubies, aquamarine, kunzite and lapis lazuli.44. “Minerals in Afghanistan,” BGS, accessed May 25, 2017, https://www.bgs.ac.uk/afghanminerals/docs/Gemstones_A4.pdf. Despite such riches being an enormous potential source of revenue for the country, Afghanistan is still struggling to implement an effective legal framework. The mining process – tendering, contracting, extraction and monitoring – is shrouded in secrecy. This enables political influence and the personal enrichment of the principals and agents involved. Consequently, despite the riches that Afghanistan possesses, the majority of the population lives below the poverty line and Afghanistan ranks as the 167th poorest country in the world and is highly dependent on international aid.55. Jonathan Gregson, “The World’s Richest and Poorest Countries.” Global Finance, February 13, 2017, https://www.gfmag.com/global-data/economic-data/worlds-richest-and-poorest-countries.

While natural resources may be a tempting resource for cash-strapped developing countries to look to in order to quickly raise capital, it is of critical importance to have an inclusive and comprehensive national strategy, a clear legal framework and competent institutions to manage and oversee the process.

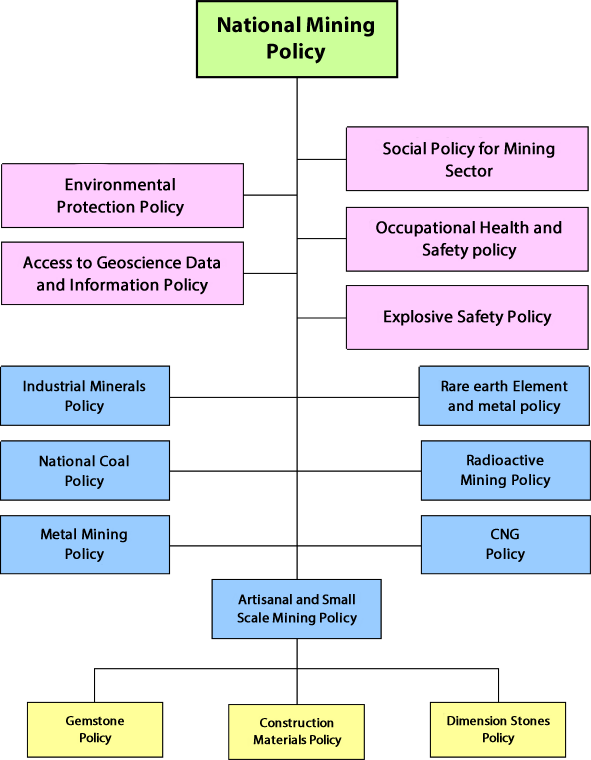

Afghanistan has a structured legal framework in relation to its extractive sector. There is both a Minerals Law and a Hydrocarbon Law,66. See “Minerals Law,” Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, Ministry of Justice, August 16, 2014, accessed May 25, 2017, http://mom.gov.af/Content/files/Afghanistan-%20Minerals%20Law-19-May-2015%20English.pdf; and “Hydrocarbons Law,” Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, March 2014, accessed May 25, 2017, http://mom.gov.af/Content/files/Hydrocarbons_Law_2009-(Unofficial_English_Translation_dated_March_2014)-Final.pdf. each of which is complimented by a set of accompanying regulations.77. “Mining Regulations,” Ministry of Mines and Petroleum, February 14, 2010, accessed May 25, 2017, http://mom.gov.af/Content/files/Mining_Regulations.pdf; and “Hydrocarbons Regulations,” MoMP, April 13, 2014, accessed May 25, 2017, http://mom.gov.af/Content/files/Hydrocarbons_Regulations_2009-(Unofficial_English_Translation_dated-April-13_2014).pdf. Added to this is a range of policy documents addressing various elements of the extractive industry, the organisation of which is set out below.

Source: National Mining Policy, Ministry of Mines and Petroleum, http://mom.gov.af/en/page/3993/7664.

This suite of legislation, regulations and policy contains admirable language in terms of rights protection and development goals. The Minerals Law, for example, has as its objective inter alia:

Despite these protections on paper, the reality on the ground is very different.

A recent report by Integrity Watch Afghanistan – based on a case study of five mines in the country – found a catalogue of errors throughout the mining process. Tender documents were often prepared in a way that favoured the winning bidder and contracts were eventually awarded to enterprises in which politicians or other Afghani government officials hold an interest, in violation of the Minerals Law that prohibits certain officials being granted licences.99. Ibid, article 16(2). The same report detailed how despite certain legislative and contractual requirements for companies to conduct social and environmental impact studies prior to extraction, none of the mines investigated had done so. In fact, they had all begun extraction before obtaining the necessary permits or paying the required royalties and taxes. Finally, the investigation found that the Ministry of Mining and Petroleum’s implementation of monitoring and accountability mechanisms was severely lacking.1010. J. Noorani, “The Plunderers of Hope? Political Economy of Five Major Mines in Afghanistan.” Integrity Watch Afghanistan, 2015, accessed May 25, 2017, https://iwaweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/The-Plunderers-of-Hope.pdf, 2-3.

This inability to translate theory into practice means that Afghanistan is being looted of its natural resources. Despite the government having an enormous amount of information about these abuses it continues to protect the interests of the mining companies. This reality means that Afghanistan scores very low on governance structures for the mining sector. In 2013 for example, it was ranked 49 among 56 countries by the Natural Resource Governance Institute.1111. “The 2013 Resource Governance Index,” Natural Resource Governance Institute, May 5, 2013, accessed May 25, 2017, http://www.resourcegovernance.org/resource-governance-index/report.

The remainder of this paper looks at several different cases of mineral extraction in Afghanistan that highlight the kinds of rights violations faced by local communities in relation to the extractive industry in Afghanistan. It concludes by examining what action could be taken to improve the situation.

The world class Aynak Copper mine is one of the many mines in Afghanistan for which private companies have been granted extraction rights. This contract was signed with a Chinese joint venture, China Metallurgical Group Corporation and Jiangxi Copper called MCC‐JCL‐JCL Aynak Minerals in May 2008.1212. “Aynak Mining Contract,” MoMP, April 8, 2008, accessed May 25, 2017, http://mom.gov.af/Content/files/MCC%20Afghan%20Gover%20Aynak%20Copper%20Contract%20English.pdf. Contrary to National Mining Policy Guidelines,1313. See for example “National Mining Policy,” Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, Ministry of Mines, Guidelines 13.3, 2012, accessed May 25, 2017, http://mom.gov.af/Content/files/Policies/English/English_National_Mining_Policy.pdf. the government tendered the copper mine without conducting even a preliminary enquiry about the communities living there, their means of livelihood, their land ownership, social structures or the local economy and environment. Although the then Minister of Mines and Petroleum Ibrahim Adel visited the local communities and made numerous promises to them, the engagement was more misleading than any well-intentioned consultation with local people.1414. “Aynak – A Concession for Change,” IWA, 2013, accessed May 25, 2017, https://iwaweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/aynak_a_concession_for_change_english.pdf.

Women are specifically affected by the mining activities due to the presence of the Aynak Protection Police, a unit of the Ministry of Interior that provides security to the company. Women already had limited access to public spaces before the extraction began. However, the new developments at the mining site further constrained women’s movement since security forces, deployed to protect the mining site, harass them. Consequently, they are forced to stay within precincts of their homes.1515. Interview with a local elder at Davo Village, which borders the Aynak Copper site, February 8, 2013.

Some communities in Aynak claim that they inherited the land from their ancestors, and the nomadic Kuchi claim pastoral land entitlement to the surrounding area. There are various claims of a community land title. For example, one of the Aynak community representatives explained that “the main village that now falls in the area reserved for mining operations is named after my great grandfather, Adam.”1616. “Aynak – A Concession for Change,” 2013. Various locals have confirmed this, stating “the land at Aynak belongs to the great grandchildren of Adam.” However, people’s properties were seized without compensation and, with exception of two people, the community has been displaced against their will and lost their livelihood.1717. Ibid. The state has comprehensively played on the side of the private company, protecting private interests and in turn depriving its own citizens of their livelihood making them ever more vulnerable.

The government awarded the chromite contract of Kohi Safi in Parwan to an Afghan company named Hewad Brothers’ Company.1818. Interview with a senior policy official of ministry of mines and petroleum, February 10, 2012. The company had no prior experience in mining. 50 per cent of the company belongs to a powerful warlord, infamous for kidnaping, land grabbing and murdering innocent people.1919. Interview with a close mineral trader who closely worked with Haji Almas, November 12, 2016. Once again, the government did not consult any communities, nor did it conduct any study before opening the contract to tender. The contract had clear exploration and extraction phases defined. However, the company’s armed men and employees moved into the area two days after the contract was signed and started extracting chromite in complete violation of the terms of the contract.2020. Noorani, “The Plunderers of Hope?,” 2015.

The district in which the chromite is being extracted is home to 42,000 people.2121. Interview with a local activist who sought to remain anonymous. The mining operation happened only 20 meters from the villages of Gahah Khile and Nouman Khile in Kohi Safi. Once again, the arrival of outsiders – including armed militia – disproportionately affected women’s movement in the community. It has become harder for them to carry out traditional work, attend social events, go to the health clinic and girls no longer go to school – all for fear of violence.2222. Interview with Molem Gul Nabi a local elder, December 10, 2016.

In addition, the people around the mine have also experienced violent conflict due to the irresponsible behaviour of the company, which led to the deaths of dozens of local people. For example, in 2012 the company recruited guards from a village named Naza Dara. However, the extraction was happening in another village, Jala Qala.2323. Ibid. People from Jala Qala felt discriminated against. The elders of Jala Qala told the company that they should be employed as guards because they are the ones being impacted by the mining.2424. Interview with Malik, December 10, 2014. Hewad Brothers’ Company eventually handed over the security to people from Jala Qala. Two months later, six former guards from Naza Dara were killed in a targeted act of violence.2525. Interview with a local elder who sought not to be named, January 10, 2015. The elders of Naza Dara suspected that these six individuals were killed by people from Jala Qala who had earlier protested against the company and asked for employment as guards. Two months later, two clergymen from Jala Qala were assassinated, Mullah Salam and Mullah Kabir.2626. Interview with Molem Gul Nabi, December 10, 2016. Following these events, Hewad Brothers’ Company disarmed the local people with the help of local police and brought in 40 armed men to protect the mine.2727. Noorani, “The Plunderers of Hope?,” 2015. However, the company kept some elders from the community on its payroll to “manage” the community and to discourage people from protesting against the company. This has led to further suspicion and seeded even more fragmentation amongst the local communities.2828. Interview with a local elder who did not want to be named, November 23, 2015.

The company’s private guards have threatened local people against speaking publically about the company. The local people felt vulnerable and resorted to insurgents, including the Taliban, to seek justice and protection, eventually forcing the company out of the region. The two communities are now locked in a violent conflict, a direct consequence of irresponsible mining in the area.

Until 1979 the government extracted about four tons of lapis lazuli every year from the mine in Keran-wa-Menjan district of Badakhshan and received good revenues, keeping control over the supply and price. The lapis lazuli extraction was estimated to be worth about US$ 50 million in annual revenues until Chinese traders started purchasing the stone.2929. Interview with a local trader, October 7, 2015. Lapis lazuli extraction then increased tenfold and the trade reached US$ 500 million annually.3030. Author’s unpublished report on the lapis lazuli mines 2016. However, during the communist regimes in the 1980s, when there was a widespread conflict in Afghanistan and Keran-wa-Menjan was insecure, Ahmad Shah Masood, a jihadi commander, extracted lapis lazuli to generate cash to continue the war against the state.3131. Interview with a Hadyatullah Hakimi a lapis lazuli trader In Badakhshan, August 10, 2014.

Since his death, militia commanders loyal to the Northern Alliance Jihadi group, with a strong base in the north of the country, have continued to extract lapis lazuli and pocket the cash. Jihadi Commander Abdul Malik is one the men who has continuously been in control of the lapis lazuli mines, except for a brief period when the contract for lapis lazuli extraction was awarded to the Lajwardin Company, backed by Zalmay Mojadaddi a former governor of Badakhshan.3232. “Kuran Wa Munjan District Badakshan Province,” Afghan Bios, 2011, accessed May 25, 2017, http://www.afghan-bios.info/index.php?option=com_afghanbios&id=2454&task=view&total=3351&start=1670&Itemid=2. Lajwardin Company promised to legally extract and generate revenues for the state and control illegal mining. This contract threatened the monetary interests of the lapis lazuli-mafia both in Kabul as well as in Badakhshan province. Consequently, a conflict ensued over control of the lapis lazuli mine between Zalmay Mojadaddi and Commander Malik, who is backed by both senior officials of government in Kabul and the local insurgent groups and to whom he paid millions of dollars annually in return for protection.3333. Interview with lapis lazuli trader from Badakhshan, January 10, 2016.

The conflict between Malik and Mojadadi has led to deaths of two dozen armed men from both sides. Abdul Malik has now taken complete control of the mine.3434. Op-cit interview with a local trader who refused to be named, December 11, 2015. After many attempts to resolve the conflict, local elders, government officials and warlords have managed to agree on some kind of sharing formula where seven people split the rent among themselves.3535. Interview with a lapis lazuli trader based in Kabul, March 15, 2015. Today, the revenue generated from the lapis lazuli mines evaporates into the black economy with some being collected by insurgents to continue their war against the government. The Keran-wa-Menjan area, where the lapis lazuli mines are located, has a population of over 8,000 people and it remains one of the most poverty-stricken districts of the country.3636. “Badakhshan – A Socio-Economic and Demographic Profile,” UNFPA, 2003, accessed May 25, 2007, http://afghanag.ucdavis.edu/country-info/Province-agriculture-profiles/unfr-reports/All-Badakhshan.pdf.

Afghanistan has widespread deposits of coal across the country.3737. Interview with Engineer Ghafar of Afghanistan Geological Survey, December 14, 2016. Coal deposits in the north and west of Afghanistan have long been extracted, sometimes under licence but also often illegally by powerful warlords, members of parliament, and other politically connected people. According to a list of illegal mining sites across the country, there are over 350 illegal coal extraction sites in two districts of Samangan.3838. List of illegal mining sites published by MoMP in 2013. The author personally visited the Dan-e-Toor region of Samangan province, where he found about one hundred illegally operated coal tunnels. A senior official from the Ministry of Mines and Petroleum also admitted that five members of parliament were operating 892 coal tunnels and illegally extracting thousands of tons of coal daily but paying very little to the government.3939. Interview with a senior official of MoMP, September 15, 2016. There are also coal deposits in Sar-i-pul, Takhar, and Bamiyan provinces that are being illegally extracted and supplied to brick-kilns or exported.

Another member of parliament, elected from Herat province, is operating two coalmines through his company, one in Herat and the other in the Western Garmak district of Samangan. He has reportedly been extracting over a million tons annually, exporting most of it to neighbouring countries.4040. Interview with the senior manager in the Khoshak brother’s company, December 22, 2015. This member of parliament allegedly does not pay royalties or taxes.4141. Noorani, “The Plunderers of Hope?,” 2015. Local people complained to local elders, the district government and the police but, instead of assisting, these institutions protected the company and pressured the local communities into allowing a smooth mining operation.4242. Interview with local people, May 12, 2015.

Despite this somewhat bleak reality, there are several steps that could drastically improve the extraction sector in Afghanistan.

The Ministry of Mines and Petroleum must spearhead these changes, ensuring a long-term vision that does not focus on short-term financial gain. Critically, the Minerals Law must be revised and have greater focus on both anti-corruption measures, in particular by recentralising the licensing system, the decentralisation of which has been a major contributor to increased corruption. In addition, stricter penalties need to be specified and more actively enforced to discourage operators from breaking the law. The tendering process must also be improved – it must be run by a team of experts according to more stringent transparency and accountability standards.

The Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Mines and Petroleum should devise a mechanism between them to guarantee that revenues owed by mining companies are collected in a regular, effective and transparent manner.

On social and environmental issues, the Community Development Agreement must be undertaken by the mining company without fail – as is required by law. This type of consultation is the only way to ensure that a community is empowered and informed. Similarly, the National Environment Protection Agency must independently manage the Environmental and Social Impact Report process and insist that companies produce the report before any mining permits are issued.

As seen above, mining operations have a disproportionate impact on women. Consequently, the Ministry of Women’s Affairs must conduct an independent assessment to better understand how to mitigate the negative impact of mining on women and ensure that a gender based approach is mainstreamed into all mining policies and legislation.

Afghan civil society needs to continue to develop its knowledge on natural resource governance in order to better equip itself for advocacy, both nationally and internationally.

Finally, the international donor community needs to work with the Afghan government to ensure that improvements are made in the sector – for example, by providing financial support to develop improved governance strategies and also for capacity building activities to guarantee proper implementation of such revised strategies.