A Developing Field

The human rights discourse is accepted by practically every government. A state can hardly portray itself openly as a violator of human rights. But how do we turn this discourse into public policy? We propose using the tools developed by New Public Management and applying them to the public policy cycle, which can be given additional substance by unpacking the obligations, essential elements, and cross-cutting principles of human rights.

The study and formulation of public policy is a recent discipline.1 It began with the well-known piece by Harold D. Lasswell, La orientación hacia las políticas, published in 1951 (Lasswell, 1992). The date is important for understanding the objective of public policy, given that World War II had ended, the socialist bloc in the middle of Europe had been consolidated, and 1950 marked the first military conflict that initiated the Cold War: the Korean War. The challenge that emerged was far from trivial; there was a new military and economic power that presented various challenges to the democratic capitalism of the United States, one of which was the efficiency of public administration through a centralized state model that controlled all means of production and then distributed goods to the population. In the face of this challenge arose the question: What is the best and most efficient system of government? For American analysts, it was imperative to develop new and efficient public policies that were built on scientific/causal theory and complemented by creativity. This was the challenge that Harold Lasswell took on to create what he called the “policy sciences of democracy”.2 It is no coincidence to read in his text:

The dominant American tradition defends the dignity of man, not the superiority of a class of man. Hence it is to be foreseen that the emphasis will be upon the development of knowledge pertinent to the fuller realization of human rights. Let us for convenience call this the evolution of the policy sciences of democracy.

(Lasswell, 1992, p. 93).

Beyond the ideological dispute that gave rise to the discipline of public policy, the important point to highlight is the final objective: to rationalize government actions. This is the main goal of analyzing public policy. One might ask oneself, “Why should I be concerned with the rationality of government action?” The answer at the time was political: capitalist democracies should surpass socialist means of production. Today, the answer is found elsewhere: state action should be guided by public welfare. When dealing with a public action that uses public resources, the objectives and the mechanisms or procedures used to determine government action should garner the greatest possible increase in welfare in the most efficient way. Thus, public policy aims to rationally address a public problem through a process of government action.

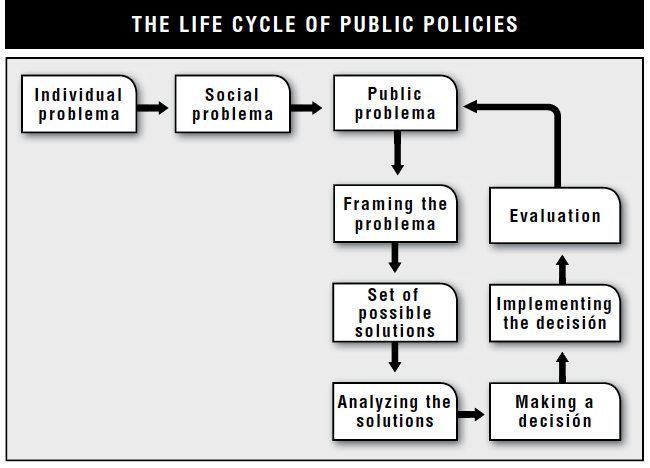

As part of this process of rationalization and analysis, the life cycle of public policy was created. From the outset, it must be emphasized that this is a process that never ends; it is a cycle that is constant and systematic. The cycle is comprised of seven processes: the entry of the problem into the public agenda, framing of the problem, designing possible solutions, analysis of the pros and cons, decision-making, implementation, and evaluation.

This figure illustrates the stages that connect the governmental decision-making process. It is not meant to be descriptive, although it does aspire to have regulatory impact. Today we know that the public policy process can follow these steps, but that it is not always and not necessarily the case. Not uncommonly, the links can merge together and the step-by-step process can become less clear.

It all begins with the appearance of a problem – but not just any problem, rather one considered to be a “public” problem. This is an essential point because social problems, or those that may affect many people, cannot always be considered public problems. For example, for a long time, the subordinate status of women was not considered a public problem. Violence against women was not considered a public problem either, but rather one that had to be resolved in the private sphere, where the state would not intervene. What is considered a public problem today was probably not considered as such before and possibly may not be considered as such later: the public agenda is always changing. When is a problem a public problem? This occurs when it is addressed by one of the many3 governmental institutions.4

Once the problem has been established, the next steps are to frame the problem and put forth various possible solutions. Framing the problem involves diagnosing the causes of the problem and identifying possible solutions. The set of solutions will depend on how the problem is framed: there is no single solution to a given problem. The framing of the problem and the design of multiple solutions, together with the decision-making phase, are the most “political” parts of the public policy cycle. This is where conflicting or competing ideologies, interests, and knowledge meet. Finally, at the decision-making stage, it is determined which of the possible solutions presents the greatest degree of technical certainty based on the available evidence. However, the political backing enjoyed by the winner of an election can be as important as technical evidence.

Once the problem has been framed and a decision has been made on how to resolve it, the public policy is implemented. This stage in the cycle is just as significant as the previous ones; there is no hierarchy of importance between the stages. Frequently, the public problem that is framed and the decision made by the government is not only the most politically viable option, but also the most appropriate to resolve the problem. However, the desired results may not be achieved. This may be largely due to the fact that reality is complex and it is difficult to anticipate all of the factors that will affect a public policy. It can also be a case of poor implementation; for example, the implementers may have disagreed with the objectives of the public policy. This can happen particularly with controversial policies, like the legalization of abortion in places with a high number of religious doctors who refuse to perform the procedure. Alternatively, while there may be agreement with the objective and goals of the public policy, the public administration may be so complex in its operations that it creates serious information problems, whereby the goals and procedures are not clearly communicated between upper-level management and the implementers.

Finally, once the public policy has been implemented, we move to evaluation. This stage may be the most technical and the one that has undergone the most development in the last 20 years. Previously, it was thought that evaluation should be done once the public policy was complete. Today, there are different kinds of evaluation for each of the stages in the cycle: evaluation of policy design; evaluation of management to analyze the implementation process; evaluation of results to verify fulfillment of the objectives; and, finally, an evaluation of impact that analyzes the achievement of the goals – in other words, whether or not the public policy had any impact on the original problem.

We now turn to a human rights perspective on public policy. A key date to remember is 1989: the fall of the Berlin Wall. At that moment, there was a significant development in international human rights law, the fall of the Wall was followed by the spectacular fall of the socialist bloc and economic conversion, social democrats replaced the parties of the right in various countries (particularly Margaret Thatcher in England from 1979 to 1990, and Ronald Reagan and George Bush between 1981 and 1992), and, by that time, various Latin American military dictatorships had ceded power to representative governments. The decade of the 1990s seemed promising due to a triumvirate of neoliberal capitalism, representative government, and human rights.5 In this process, human rights took on two discursive possibilities: they continued to be used as a discourse of protest against governments, but also, due to the success of this triumvirate, governments could not easily oppose them publically. On the contrary, governments often present their platforms in terms of rights. The new question is, “How can we implement them from within the government?” It was in this context that the World Conference on Human Rights was held in Vienna from June 14-25, 1993.

One of the central elements of the conference’s Declaration and Program of Action was the need to establish public policies that address human rights. For example, paragraph 69 recommends the establishment of a global program within the United Nations that provides technical and financial assistance to States to reinforce their national structures, enabling them to be in observance of human rights. Similarly, paragraph 71 recommends that States develop national action plans to improve the promotion and protection of human rights. Finally, paragraph 98 establishes the need to create a system of indicators to measure progress in the realization of economic, social, and cultural rights (ESCR). The mandate to carry out these three actions was given to an institution that was also proposed in this conference: the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR).

A critical juncture in the development of public policy analysis in the last quarter of the 20th century was the creation of the concept of New Public Management (NPM). The birth and development of NPM coincided with the neoconservative process of the 1970s and 1980s. NPM is concerned with improving the efficiency of public administration, evaluating processes and results, and providing high quality public services, but its ideology asserts that all of this is best achieved with less state intervention and a greater role for markets. Some of the measures that have been applied globally since the late 1970s and early 1980s to reduce the role of the state include the elimination of government programs, the privatization of companies and public institutions, cuts to public expenditures, the opening of markets through deregulation and reduced tariffs, the creation of new autonomous institutions, innovative ways to allocate public resources, decentralization, and shared responsibility in the provision of public services.

To achieve greater efficiency, the state should increasingly resemble a private firm. The key to understanding this model rests in the well-known book by David Osborne and Ted Gaebler, Reinventing Government: How the Entrepreneurial Spirit Is Transforming the Public Sector, (OSBORNE; GAEBLER, 1994), which traces the trend of public policy throughout the 1990s to apply business and economics principles of efficiency through competition. The suggestion to make private schools compete with public schools, or private clinics with public clinics, through vouchers that the state would provide to citizens to use with the service provider of their choice, was first made by Milton Friedman in Capitalism and Freedom and Free to Choose (FRIEDMAN, 1966), and it established the principles for this new kind of management.

One of the key phrases for understanding this stance is “steering, not rowing.” The state can privatize all public services deemed unnecessary to be provided by government entities. Furthermore, transferring these services to the market guarantees a greater level of efficiency and a better cost-benefit ratio. The critical point is that the state must have the capacity to steer the boat, establish criteria, and regulate companies in order to ensure the quality of services provided.

While there had been serious criticism made of the neoliberal model since its early implementation, the outcomes at the end of the 20th century brought into question many of the premises that bound NPM to the neoliberal revolution. For example, the disastrous consequences of the rapid mobilization of capital on the quality of life of the population were evident in the Tequila Crisis of 1995, the Asian financial crisis in 1997, the Russian financial crisis in 1998, the Samba effect in 1999, and the Tango effect in 2001. However, the most serious questions were raised during the global economic crisis that began on Wall Street in December 2008.6 During that time, specialists on ESCR found it more and more difficult to reconcile the neoliberal model with the ability to plan and implement ESCR. This was evident in the reports of the Special Rapporteurs of the United Nations on the rights to life and health and the impact of extreme poverty on human rights.

The question is, can we separate the neoliberal reforms from NPM now that they have been fused? We should at least try because one of the primary objectives of NPM is worthwhile: to make public administration function efficiently and put in place mechanisms to determine if that is the case. NPM:

sets itself up as a new way to understand government action and legitimacy, not based on a vision of strictly following legal procedures, or maintaining a bureaucracy guided by an ethic of responsibility, but rather based on creating systems of incentives and measurement that make a positive impact on the behavior of public servants, so that efficient and worthwhile results can be obtained for the population.

(GESOC, 2009, p. 4).

The primary objective of public policy is to rationalize the use of scarce resources in the state’s fulfillment of activities in each of the stages of the cycle. It does not seem to matter what the state has to do; rather, what matters is that the state does it well and efficiently. These principles are about form more than substance: they do not tell us anything about which activities correspond to the state, which activities should be left to the market, or which are fundamental values that should be realized through state action. In contrast, a human rights perspective emphasizes that the international obligations that the state has assumed should be clearly expressed and implemented through its public policy…without concern for exactly how it is done. From this point of view, the relationship is clear: the human rights perspective determines the objectives and NPM determines the means.

Earlier, we stated that public policy is concerned with reviewing the decision-making process used by state actors and analyzing and perfecting the rationality of these processes. By ‘rationality,’ we mean a series of attributes that one would like to see in any public policy: efficiency, efficacy, economy, productivity, and timeliness.7 If the principal objective of public policies is to lend rationality to state action, this means that public administration should be guided by these principles. Thus, public policy is a collection of procedures that includes government allocation of inputs (financial, human, information, etc.), obtained under the principle of economy and processed with an eye to productivity, in order to obtain products that generate certain results in the short term. Between the provision of inputs and the realization of the outcome, we expect to observe an efficient logic. Furthermore, these short-term results should contribute to increased effectiveness in the realization of medium- and long-term impacts. This whole process should also be cost-effective in terms of inputs, processes, and impacts (GESOC, 2010).

Ensuring that the state uses its available resources in the best possible manner should not be seen as contrary to a human rights perspective. All human rights require dos and don’ts by all the various government entities, budgets, and planning processes. Therefore, it is important to have a human rights perspective but also to have mechanisms to evaluate implementation, management, results, and impact. The objectives derive from human rights and the procedures come from NPM.

Two of the main characteristics of a human rights-focused public policy are people’s empowerment and compliance with international human rights standards. Both aspects are guided by the central element of human rights: human dignity. In this sense, freedom—in the form of self-determination—is one of the key aspects in the development of the idea of human dignity. It is the foundation for empowerment. Likewise, international standards carry a set of rights that appeal to superior, higher needs like freedom, equality, peace, etc. (FERRAJOLI, 1999, 2006). This collection of higher needs constitutes universal morality, which supposes, again, that human dignity is the ultimate goal of human rights (SERRANO; VÁZQUEZ, 2011). We will start with the first characteristic, people’s empowerment.

One of the main elements in the recognition of human rights is the construction of a rights-holder. This is linked to the liberal roots of human rights. It is taken as given that the creator of public power is the subject: the subject is the beginning and the end of the political system.8

Most of the discussion around the construction of the rights-holder has centered on the right to development and the right not to be poor. This seems fitting if we consider that poverty implies being deprived of multiple things and various rights, that together limit the right-holder’s capacity for self-determination and the ability to exercise power. It is important to clarify that this capacity for self-determination depends on economic factors, but also on cultural, social, and political factors. Thus, limitations on self-determination are not just economic; there are multiple deprivations that arise from cultural, social, and political contexts. A lack of self-determination has multiple causes. Part of the strategy of human rights is to weaken that cycle of powerlessness and promote enhanced skills (NACIONES UNIDAS, 2004). This is where empowerment of the individual is linked to rights to equality and freedom from discrimination, to affirmative action and gender, to the identification of both vulnerable groups and the elements that generate conditions of structural oppression and the modification of those structures (not just through affirmative action but also through transformative action). It is clear that human rights are interdependent, comprehensive, and therefore indivisible.

We can think about empowerment by considering an essential question: How can a channel of communication be built between the government and the people? If the population continues to be treated as subjects—in other words, a right is granted as a favor through the magnanimity of the monarch using policies of patronage—then there is no empowerment; there is no public policy based on human rights.9 One could ask, “How does the human rights perspective propose to create rights-holders?” The primary and most well known way, though not the only way, is through recognition of the right. That implies identifying the core and the extremes of the right, to determine, through public policy and with evaluation indicators, how to progressively fulfill the right; it assumes that there are information campaigns to make people aware of their rights; it also assumes that there are enforcement mechanisms (jurisdictional and non-jurisdictional) to implement the rights, both in general and within specific public policy programs. Here, the language of rights is extremely important, because it creates a logic of responsibility through accounting mechanisms and legally binding obligations. Seen through this lens, the objective and the essence of public policy is not to solve specific problems or to respond to unsatisfied demands but, rather, to fulfill rights.

Finally, the concept of empowerment as a basic element in the creation of a human rights perspective will have a major impact in the course of public policy planning because it will lead to the consideration of two criteria: acceptability, and the overarching principle of participation. Both of these will be reviewed in the next section.

Since the release of the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man under the Inter-American human rights system and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights under the United Nations in 1948, we have experienced a “boom” in international legislation10 that has been complemented by the general observations and resolutions of United Nations committees,11 and by the resolutions issued by different courts of human rights,12 as well as by UN rapporteurs who have different thematic or country mandates.

The development of international human rights law in the second half of the 20th century generated diverse international obligations for States at all levels (federal, local, and municipal) and relative to all of their functions (executive, legislative, and judicial), which can be grouped into four categories:13

• The obligation to respect: No State entity may violate human rights, through either action or omission.

• The obligation to protect: State entities should prevent private entities (companies, unions, individuals, religious groups, associations, or any other non-state institution) from violating human rights.

• The obligation to guarantee: States are required to organize the government in a way that allows people to exercise their rights. It can be sub-divided into four obligations: the obligation to prevent human rights violations, the obligation to investigate human rights violations, the obligation to punish the intellectual and material authors of human rights violations, and the obligation to make amends for infringement on victims’ rights.14

• The obligation to fulfill: State entities should take action to facilitate compliance with international human rights obligations.

In addition to human rights obligations, international standards also require adherence to a basic standard for each right, which are detailed by the United Nations Committees in their general observations. For example, compliance with obligations regarding primary education are not satisfied by establishing a certain number of schools, rather, the State is required to take action to fulfill certain standards guided by these basic principles:

• Availability: The means to guarantee sufficient services, facilities, mechanisms, procedures, or anything else needed to bring a right to fruition for the entire population.

• Accessibility: The means through which a right is realized should be accessible (physically and financially) to all persons, without discrimination.

• Quality: The means and content that bring a right to fruition must have the necessary requirements and properties to be able to fulfill that function.

• Adaptability: The means and the content chosen to bring a right to fruition should have the necessary flexibility so that they can be modified and adapted to the needs of changing societies and communities and respond to different social and cultural contexts.

• Acceptability: The means and the content chosen to bring a right to fruition should be accepted by the target beneficiaries. This is closely linked to adaptability, and to criteria like ownership and cultural adaptation, as well as citizen participation in the formulation of the policy in question.

The last set of principles that should be taken into account when “unpacking” how a right relates to application: identifying the core of the obligation, progressiveness, a prohibition on regression, and maximizing the use of available resources.

Identifying the core element of a right implies establishing the minimum requirements that the state should provide immediately, to anyone, without arguing that it cannot be done due to scarcity of resources or similar issues. The fact that the core of the obligation has been identified does not mean that the right cannot be expanded—one must remember that human rights establish a floor, not a ceiling on each right. Expansion happens based on the principle of progressivity and a prohibition on regression. Once progress has been made in the enjoyment of certain rights, the state cannot, except in certain circumstances, scale back what has been achieved. Now, one might ask, how can we observe and guarantee that? One useful tool is to look at the maximization of available resources. A budget analysis can reveal, first, what quantities were available, and second, how they were used. For example, if a good year leads to greater income than was anticipated, and that extra amount is spent on ordinary expenditures—cell phones, vehicles, etc.—then we can legitimately argue that the principle of maximizing available resources was violated.

The specific content of each of these obligations, essential elements, and principles of application will vary depending on the right to which they are applied. For example, for obligations relating to respect for, protection, guarantee, and fulfillment of the right to health–taking into account the criteria of availability, accessibility, quality, adaptability and acceptability–their content will be different than that used to realize the right to education, the right to water, or the right to vote and be elected (although the categories of obligations would remain the same). Thus, when using a human rights perspective, the first course of action before doing a diagnosis and planning a public policy is to generate a “map” of the right, or to “unpack” the right. This map, likely comprised of a number of obligations, will provide the content for the public policy.

When thinking about international standards, it is important to identify the central element that will provide a foundation for public policies that have a human rights perspective. We are referring to the need to turn to the treaties and declarations that generate obligations, to the jus cogens, to international custom—in other words, to all of the sources of international human rights law, including general observations, rulings, rapporteurs’ reports, programs and plans of action resulting from human rights conferences, and other documents that help establish the content and extremes of international human rights obligations. In this way, if we were, for example, doing an analysis of a public policy related to health, we would need to review all of the aforementioned documents in order to establish the obligations to respect, protect, guarantee, and fulfill the responsibility by the state in the area of health. With these elements in place, we will have created the international normative standards with which we would expect the State to comply for the topic in question.

International treaties, general observations of UN committees, and reports and case law from regional and international human rights courts establish other fundamental principles that decision-makers should observe in a cross-cutting manner when formulating and implementing public policies. Among these minimum standards, we find rights and principles like equality, non-discrimination, participation, coordination between different levels of government, a culture of human rights, access to information, transparency and accounting, and access to enforcement mechanisms. We elaborate on these themes below.15

Equality and non-discrimination are two principles that are established in numerous international instruments16 emphasizing equality in the enjoyment of all human rights. These instruments require that States Parties guarantee the exercise of rights free from any discrimination based on race, color, sex, language, political or other opinion, national or social origin, economic status, birth, physical or mental disability, health status (including HIV/AIDS), sexual orientation, marital status, or any other condition of a political, social, or other nature. This set of norms, as well as the case law relating to them, provides clear concepts and useful parameters to define and evaluate public policies.

The principles of equality and non-discrimination oblige States not to discriminate, in other words, not to implement policies and measures that are discriminatory or that have discriminatory effects, and it also obligates them to protect people from discriminatory practices or behavior by third parties, whether these are public agents or non-state actors. Similarly, it implies that States give attention to the particular circumstances of persons and groups who are excluded or discriminated against in order to ensure that they are treated on the basis of equality and non-discrimination, and that they are not neglected.

The Inter-American human rights system uses the concept of material or structural equality, emphasizing that:

certain sectors of the population require special measures of equality. This implies the need to provide differentiated treatment when the circumstances affecting a disadvantaged group mean that equal treatment can only be achieved by restricting or worsening access to a service or good, or the exercise of a right.

(ABRAMOVICH, 2006, p. 44).

The intended beneficiaries of these kinds of measures are the victims of historical processes of discrimination and exclusion. These include indigenous populations and women, as well as those who are in situations of vulnerability as a result of structural inequalities. The latter include children, undocumented migrants, displaced persons, and persons with HIV/AIDS, among others.

One of the primary obligations of the State is to identify the groups within its territory that need special or priority attention to be able to exercise their rights. It must then approve laws that protect these groups from such discrimination and, within its policies, plans of action, actions, and budget, incorporate concrete measures to protect them, compensate them, or strengthen their access to rights.

One of the central elements related to the construction of the rights-holder and the empowerment of the individual is the belief that that the individual is best placed to make his or her own life decisions. In theories of democracy, there is a moral equality that follows from the categorical principle of equality: people’s desires for goods, their moral demands, and the sorting of their preferences are equally valid despite their differences. At the same time, without evidence to the contrary, each individual is best placed to determine those desires and preferences, to define one’s own good life. Using this logic, the individual not only can but should participate in making political decisions as part of his or her self-determination.

Participation is another element related to the construction of the rights-holder that generally garners agreement. However, problems emerge in determining the various procedural elements: What forms will participation take? How do we get the ruling class to internalize public concerns? What criteria will determine the participation of republicans, communitarians, “deliberativists,” and liberals? To what extent will we maintain a representative democracy—or will we change to a direct democratic system? If we stick with the former, are NGOs good representatives of civil society? If we go with direct democracy, what would be the optimal design of regional or national decisions?

International human rights law documents have established some parameters. The right to participation and consultation in public matters, established in various international instruments,17implies the active, documented participation of all persons who are interested in the formulation, application, and monitoring of public policies. International instruments relating to indigenous populations also establish their right to be consulted and to participate in the formulation, application, and evaluation of national and regional development plans and programs that may directly affect them.18

The capacity of civil society to engage in public policy will depend on the institutional context. This institutional context must be conducive to the creation and institutionalization of effective mechanisms to allow for the participation of social, community, and civil society organizations in the oversight, decision-making, and evaluation processes related to public policies, programs, and actions, ensuring that there are adequate, timely, accessible, and understandable consultation and information mechanisms. It will also depend on “the appropriation by social organizations of monitoring mechanisms, and the existence in civil society of actors with the desire and the resources to use them” (ABRAMOVICH, 2006, p. 47). Advocacy can occur through the filing of legal claims, the organization of campaigns to influence public opinion, or the organization of protests or mobilizations, among others.19

Public policy advocacy, is defined by Canto (2002, p. 264-265) as “a conscious, intentional process by citizens to influence, persuade, or affect the decisions of institutional elites,” which clearly includes the government, “in order to generate a change or transformation in the courses of action aimed at solving particular public problems.” Public policy advocacy requires civil society organizations to have specific capacities and skills, which vary according to the different stages of the public policy cycle. The author highlights organizational capacity, technical skills, political skills, and social tradition.

Human rights are indivisible, comprehensive, and interdependent. This means that there is no hierarchy between them. Fulfillment of a right entails the fulfillment of others, and the violation of one right can lead to the violation of others. Therefore, their realization requires action that is coherent, planned, and coordinated through permanent forums and mechanisms for exchange between all branches and at all levels of government. The direct consequence of this is that when a human rights perspective is applied to public policy, it tends to be holistic.

Human rights policies should include actions, plans, and budgets for different sectors and public entities, which should act in a coordinated way to break the paradigm of departmental competition (inter-departmentalism). Likewise, they should facilitate coordination between the different territorial levels of government: national, provincial, and municipal (inter-governmentalism).

As a result, there is a need for ongoing coordination between public officials at the different levels of government, respecting autonomy and in accordance with the principles of concurrence, coordination, and the subsidiarity of government action. Likewise, de-concentration, delegation, and decentralization should be used within each level of government, together with high levels of social and political responsibility.

(JIMÉNEZ BENÍTEZ, 2007, p. 43).

This is one of the primary differences between traditional public policy and policy that uses a human rights perspective. The former is much more focused on specific problems, whereas the latter is much more holistic, viewing barriers to the exercise of rights as a “public problem.” These differences will be taken up again later.

The 1993 Vienna Declaration and Program of Action establishes that:

(…) education on human rights and the dissemination of proper information, both theoretical and practical, play an important role in the promotion and respect of human rights with regard to all individuals without distinction of any kind such as race, sex, language or religion.

(NACIONES UNIDAS, 1993, Art. 33).

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has made significant progress in promoting strategies and producing information and materials on this topic. In Mexico, education for peace and human rights, promoted by civil society organizations decades ago, has gradually been integrated into the public sector’s regular set of responsibilities, falling first to some autonomous organizations and more recently to public institutions.

The consolidation of a culture of respect for human rights implies, on the one hand, raising the public’s awareness of human rights through campaigns and other dissemination activities and promoting a culture among citizens of the enforceability of rights. On the other hand, it includes training public servants at all levels and in all government entities on human rights in general and on human rights as they relate to public policies and budgets.

To build this human rights culture, we must make use of both formal and informal education, taking into account that we must educate about human rights as well as for human rights. Finally, it is essential that human rights education directed at public servants be accompanied by institutional change that allows for new incentives and disincentives that promote compliance with human rights obligations. Training alone will not change the state of inertia if it is not complemented by adequate institutional incentives. Here we arrive at another point: while education on human rights is important, developing a set of values around human rights is a long-term process, which surely will not be achieved in a first or second generation; hence, institutional design is key.

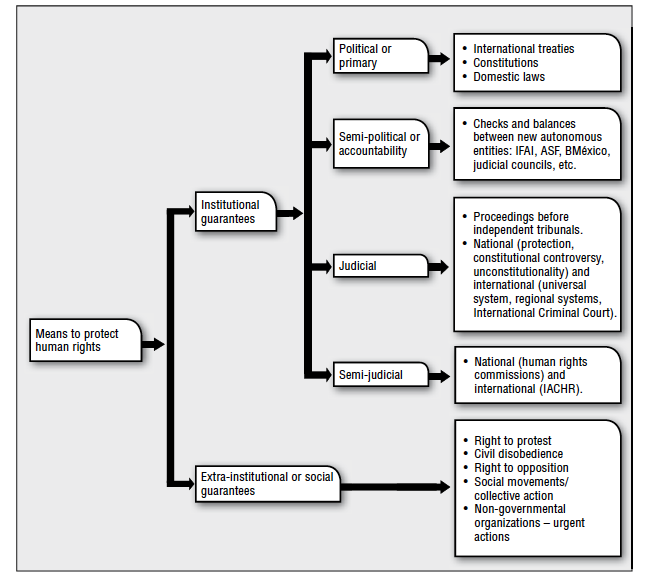

The last of the cross-cutting principles is the establishment of enforcement mechanisms. As with the concept of people’s empowerment, the starting point for formulating a policy is no longer the existence of certain social sectors that should be “helped” through the provision of welfare or discretionary benefits, but rather, as Abramovich emphasizes (2006, p. 40), “the existence of people who have enforceable rights, i.e., entitlements that give rise to legal obligations for others and, consequently, to the establishment of safeguard, guarantee or accountability mechanisms.” According to Gerardo Pisarello (2007) and Luigi Ferrajoli (1999, 2006), a first distinction can be made between institutional and extra-institutional or social guarantees. The former includes what Pisarello calls political guarantees, or what Ferrajoli calls primary guarantees. These guarantees are constituted through processes of positivization of rights, which can happen at the national or international level.

Semi-political mechanisms come from the already classic mechanism of checks and balances, which is now referred to as horizontal accountability, complemented by new autonomous organizations. All of the transparency and accountability mechanisms largely enter here. The right of access to information includes the right of individuals to request and receive public information, allowing them to evaluate and supervise the policies and public decisions that affect them. The State has a corresponding obligation to provide the requested information, and generally to guarantee transparency of public functions and to publicize the actions taken by the government. A human rights perspective helps to formulate policies, laws, regulations, and budgets that are based on the definition of reference points, priorities, goals, indicators, those responsible, and resources. This can ensure that the process of policy formulation is more transparent, and that those who have the duty to act are held accountable (NACIONES UNIDAS, 2006c, p. 17).

Pisarello’s jurisdictional guarantees, and Ferrajoli’s secondary guarantees, are the proceedings in independent courts at the national or international level. Here, it is critical to stress that “it is not impossible either in theory or in practice to also design enforceable rights in the field of ESCR” (ABRAMOVICH, 2006, p. 48). By virtue of international human rights law, all persons have the right of access to justice; that is to say, to be able to count on effective, simple, and quick judicial resources or to appeal to a judge in order to seek protection against any violation of their human rights.

Finally, we have semi-jurisdictional mechanisms, which refer to human rights bodies like commissions or ombudsmen. Extra-institutional guarantees, in turn, refer to the whole set of collective actions used to demand rights.

This summary of cross-cutting human rights principles does not aim to be exhaustive, but rather to detail the principles that we consider most relevant and most developed. As international human rights law continues to develop, the principles become increasingly detailed and are complemented by new rights and principles. In particular, it is worth highlighting the recently developed concept of sustainability, which emphasizes the need to incorporate the concept of sustainability into the design, implementation, and evaluation of public policies and programs in order to ensure that conditions are in place to satisfy the needs and fulfill the human rights of current generations without compromising those of future generations.

We have come halfway. Now that we have clarified what international standards are, and how they are constructed, we turn to the most interesting challenge: How do we turn these international standards into public policy?

We proceed by identifying the international human rights obligations that are applied to existing public policy tools. Various tools were developed as a result of the need to rationalize public policy; these include public policy plans and programs that include both logical frameworks and different evaluations that are done throughout the public policy cycle. The objective is to have the human rights perspective permeate the entire public policy cycle, and therefore each of the processes that make up this cycle should be equipped with a human rights perspective.

The main objective of public policies that utilize a human rights perspective is the fulfillment of the rights of all persons; this is one of the primary characteristics distinguishing them from traditional public policies. When thinking about framing a public problem for a policy, one should keep in mind that the ultimate objective of the policy is the effective exercise of the right that is related to the problem. That is the goal of public policy according to this perspective. For example, if there is a problem with a woman’s personal integrity being violated through domestic violence, the structural logic does not arise solely from the solution to that individual problem, but rather, from respect for the right for all individuals to a life free from violence.

There is a second important difference: to the extent that human rights are comprehensive, interdependent, and indivisible, public policies that use a human rights perspective are necessarily holistic. The human rights perspective does not refer to a specific field, or to the actions assigned to human rights institutions or to some specific right such as personal integrity. Rather, it means givingall state policy a human rights perspective: giving a human rights perspective to the National Development Plan, the environment program, agricultural policy, programs on social policy, water, security, fiscal policy, youth, senior citizens, indigenous populations, migrants, the administration of justice, and so on. In this sense, it is a kind of cross-cutting “umbrella,” leading to a normative standard that looks at all public policy to verify that it complies with a human rights perspective.

These two differences between traditional public policy and that done with a human rights perspective will have a major impact on the whole lifecycle of public policy, including the creation of a committee to facilitate intersectoral coordination and framing of the problem through a diagnostic study. This coordinating committee should be broad and participatory, and should include the multiple branches of government (executive, legislative, and judicial) as well as autonomous organizations, civil society organizations, and academic institutions. The participation of specialized international organizations is also advantageous and enriching. Given that public policy that uses a human rights perspective is openly holistic, many of its objectives entail actions by all three branches at the different levels of government (federal, local, and municipal). Additionally, if power is strongly divided between different parties, it is worth thinking about having those major parties represented on the coordinating committee. As the reader can imagine, this kind of combination is complicated; getting so many actors with different—and even contradictory—agendas and principles to participate could be doomed to failure. While it is true that a participatory process of this nature seems very complicated, it is also true that a committee that is not participatory and that does not represent a country’s main political powers (broadly defined) may be able to come up with a plan but is unlikely to implement it.

The first step to take in applying a human rights perspective to public policy is to unpack the right in question, using the elements analyzed in the previous section. Once the right has been unpacked, a mapping of the institutional design of the entity (national, local, a specific branch or area, etc.) to be analyzed will be done. Who is responsible for which human rights obligation? It is best to map it out up to three levels (secretary, sub-secretary, and department head). This mapping can help to identify which entities are directly responsible for the obligations arising from international human rights law, what they are doing about it, how they are doing it, and what remains to be done. This feeds into the diagnostic study, which ultimately aims to identify the structural causes of a right not being exercised. The study is fundamental for the process of rationalizing public policy, because it allows for the framing of problems and the design of solutions that are based on empirical evidence (evidence-based policy). A key point is that the development of the diagnostic study necessitates the use of official information, but also information from other sources. Furthermore, a common problem is a lack of available information for diagnosing an obligation of a certain right.20

In recent decades, documentation, complaints, and lawsuits (including individual and collective cases of human rights violations before national courts and regional and international protection bodies), and reports and evaluations on compliance with human rights have demonstrated the growing interest of the international community. In processes where States appear before United Nations committees, civil society organizations play an important role by presenting an alternative to the official information on the status of human rights in their respective countries. Examples include the official and “shadow” reports presented to United Nations bodies that supervise the application of international human rights treaties in different countries; national and state surveys are also useful sources of information for the drafting of the diagnostic study. In addition, international non-governmental organizations like Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, the International Federation of Human Rights Leagues, and the World Organization Against Torture publish annual reports on human rights practices around the world, particularly on those countries that have the greatest number of cases of human rights violations and abuses committed against human rights activists.

These research reports are primarily composed of qualitative narratives, which aim to provide a more or less broad and detailed panorama of the empirical reality on human rights in a given country, mobilizing two differentiated but complementary approaches. One approach favors an assessment of the human rights situation of the population in general or of specific groups (women, children, persons with disabilities, indigenous groups, etc.). The other approach seeks to measure the extent to which the State has fulfilled its obligations. In the first case, the intent is to give a broad perspective on the degree to which rights are enforced and satisfied in practice; to accomplish this, statistical information is used to illustrate aspects of the right and identify red flags. The second approach analyzes the legislative, administrative, programmatic, or budgetary efforts that the State has made in order to generate suitable conditions for the fulfillment of human rights in the country.

Planning is a central component of public policy. Regardless of whether we are talking about the short, medium, or long term, citizens’ future aspirations—interpreted by governments—tend to become expressed in public policy plans with objectives that will later be subject to evaluation. This is a critical characteristic of public policy: it is not made up of disjointed events but, rather, by a series of moments and steps that form a continuum. Even public policies formulated with the specific objective of solving a given problem need to have a plan to frame, address, and solve it. In terms of human rights, UNHCHR published a Handbook on National Human Rights Plans of Action that explains the importance of creating national human rights plans and describes the main stages in plan development and some strategies that can help planning processes come to a satisfactory conclusion.

For a time, it was thought that public policies that referred to human rights were constrained to the activities and obligations of human rights institutions, like commissions or ombudsmen. When considering human rights plans or budgets, for example, the discussion was limited to the sums given to those institutions to finance their activities. However, just as women’s rights are not synonymous with a gender perspective, the activities of human rights institutions are not the same as public policy formulated under a human rights perspective. The intent is to incorporate a human rights perspective into all state policies; in other words, to make human rights the end goal of public policy.

The climax of the programmatic structuring of public policy supposes that, once the human rights diagnostic survey has been done, the rights that will inform the plans are identified, a map of the State’s relevant international obligations is drawn, which obligations have not been fulfilled and the structural causes of the lack of enjoyment of the right are analyzed, and the strategic approach and the actions that will be undertaken to remove those causes are discussed and planned. Only then does the most complicated part begin: executing, verifying, and evaluating the plan.

One last notable point: although, according to international human rights law, aspects of the federal organization of a state are not sufficient justification for municipal, provincial, or federal authorities to fail to carry out any of their obligations—though they may claim that doing so is impossible due to their different purviews—it is also true that distribution and coordination by different government entities required to fulfill human rights obligations is far from simple. The UNHCHR office in Mexico has made an interesting shift in their public policy planning with a human rights perspective by moving from national plans to provincial plans or plans to be implemented by federal entities. After a first set of plans was created at the national level, it became clear that some problems had to be resolved through local strategies, hence the importance of these new kinds of planning.

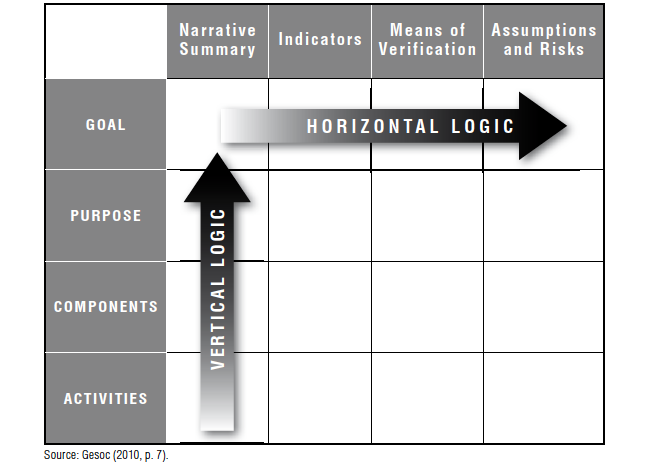

A process of administrative reform and modernization was conceived based on the notions of NPM. From this emerged the use of the Logical Framework Matrix (LFM), promoted by the U.S. Agency for International Development in the early 1970s and taken up in the 1990s by international financial institutions like the Inter-American Development Bank and the World Bank. Domínguez and Zermeño (2008) explain that the logical framework used in project planning, monitoring and evaluation processes tries to synthesize, in a single matrix or table, the key aspects of a project—in other words, the objectives, products, activities, and indicators—as well as the external conditions that affect the project and the realization of its objectives.

GESOC (2010) explains that a logical framework functions by using two logics: vertical and horizontal. The vertical is a narrative summary that presents the causal logic linking the objectives of the program. It is comprised of four elements, which are read from bottom to top:

Activities: The tasks or key actions required to produce each of the components sought by the program.

Components: The program strategies and the outputs of the interventions.

Purpose: The program’s desired result, and how the situation will change based on the program’s outcome.

Goal: The broadest objective to which the program contributes (its impact). This establishes how the program will help solve a given public problem (GESOC, 2010, p. 7).

The horizontal logic is comprised of three columns that describe how achievements will be measured, sources of information, and preconditions for the success of the policy in question. These columns are conceptualized as follows:

Indicators: These measure the performance of the program and are critical for effectively monitoring the fulfillment of objectives at each level.

Means of Verification: These identify the source of information used to measure performance indicator data at each level.

Assumptions and Risks: These are conditions beyond the control of the program, but their presence or absence affects the realization of the program’s objectives (GESOC, 2010, p. 7).

The following is an example of a logical framework matrix:

The key to giving the matrix a human rights perspective is that the end goal, or the desired impact of the public policy, is always the effective exercise of a right. Thus, the rest of the boxes (purpose, components, and activities) will automatically take on a human rights perspective, and human rights indicators will be established.The results-based focus promoted by NPM brings with it a series of problems, including the very definition of the objectives sought with this type of tool. Generally, these reforms are motivated by the government’s own objectives—such as saving and efficiently spending public resources, or strengthening managerial control measures and accountability—which do not necessarily imply the creation of public value that will be appreciated by citizens (GESOC, 2009, p. 23). For example, in Mexico, the federal government has implemented NPM from a managerial perspective with a clear results-oriented vision, using a strategy that integrates indicators to measure and evaluate performance and has a double objective: “to rationalize the resource allocation process, and to modernize public management” (ZABALETA SOLIS, 2008, p. 44).

For its part, in recent years the government of the Federal District of Mexico City has taken initial steps to build an integrated results-oriented strategy. The intent, again, is to improve the efficiency and efficacy of public spending. However, it introduces a new element: a willingness to align the objectives and results of government action with the satisfaction of people’s political, civil, social, cultural and environmental rights, and with a gender focus that seeks to remove inequalities between men and women.21 The Federal District government’s intention is to build a model for planning, programming, budgeting, and evaluation that has a focus on creating public value, beginning with a recognition of the state’s international obligation to respect, protect, guarantee and satisfy human rights, with a gender perspective.22 Still, the Federal District’s efforts are new and have a number of limitations.23

Each of the stages of the public policy cycle can be evaluated. We can evaluate decisions, program design, program management, results, and impact. If international human rights standards are used to inform the goals and objectives of the public policy, using an LFM, then the indicators proposed for those evaluations (perhaps with the exception of an evaluation of program management) automatically refer to the fulfillment of rights.

Developing indicators is key to being able to carry out an evaluation. In recent years, the topic of indicators has been at the center of debates around measuring progress or deterioration in the realization of human rights. The idea is to be able to add a quantitative angle to the evaluation and to define more systematic measurement methodologies and criteria. Among other things, the discussion revolves around the possibility of creating a set of comprehensive and reliable indicators, which, given the indivisible and interdependent nature of human rights, are applicable for the fulfillment of civil and political rights as well as economic, social, and cultural rights.

In its recent report, Using Indicators to Promote and Monitor the Implementation of Human Rights,the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (NACIONES UNIDAS, 2008) identifies three types of indicators:

1. Structural indicators: These reflect the ratification and adoption of legal instruments in accordance with international human rights standards and the existence of basic institutional mechanisms (institutions, strategies, policies, plans, programs, etc.) to facilitate the realization of a given right. They measure the State’s commitment to organizing the legal system and institutional apparatus in a way that allows it to fulfill its obligations.

2. Process indicators: These measure the reach, scope, and content of strategies, policies, plans, programs, or other specific interventions that aim at having an impact on the exercise of one or more human rights. These indicators seek to measure the quality and magnitude of the State’s efforts to implement rights.

3. Result indicators: These reflect the real impact of the State’s interventions on the status of rights. They describe individual and collective achievements that reflect the degree to which a human right has been fulfilled in a given context.

In addition to these three categories of indicators, there are others that relate to cross-cutting norms or principles that may not be connected to the realization of a given human right, but that show the extent to which the process to apply and make human rights effective is, for example, participatory, non-discriminatory, transparent, and so on—that is to say, that it complies with the cross-cutting principles of application.

For an indicator to be useful, it must first be clear and directly linked to something that interests us and is explicitly mentioned in one of the tools to rationalize public policy, ideally the LFM. The creation of a useful indicator should be related to an activity, component, goal, or result of the public policy.

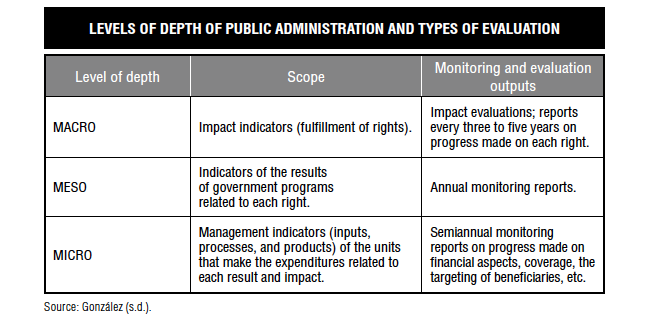

A separate challenge arises from the impact evaluation of the implemented public policy. To address this topic, it is worth distinguishing between the different levels of public administration. We can consider three levels: the macro level, which deals with the long-term impacts of the public policy; the meso level, which includes short- and medium-term results; and the micro level, which refers to particular administrative units and, in some cases, to particular public officials, where administrative management can be analyzed (GONZÁLEZ, s.d.).

The final stage, before the public policy cycle begins anew, is the impact evaluation. Here there is an interesting point to highlight: unlike the indicators established in the logical framework, this evaluation includes a different set of indicators to measure the different obligations and components for each of the rights.

Following the methodology proposed by Anaya Nuñoz (2008), the first step in defining human rights indicators is the development of a clear and detailed definition of the content of each right, identifying its distinct components or attributes; this could be done using the “unpacking” process described above. The next step is to operationalize each component or attribute—that is to say, to select various indicators for each component and define how each indicator will be measured. The set of indicators comes from the “unpacked” right. Each of the obligations and essential elements of a right should have at least one indicator. Just as there can be dozens of obligations, there can also be dozens of indicators. The set of indicators should make up an index, which will show us the situation of the right in question at a given moment prior to program implementation. This index serves as a baseline, and it should be reapplied at least once per year to determine the status of the right in the long term. After the implementation of the public policy, and after an evaluation has been done of the design, management, and results, an impact evaluation should be done. The expectation is that performance on the index in general (or some of the obligations or essential elements in particular) has improved relative to the baseline measurement, as a result of program implementation.

If implementation was done correctly, with acceptable results for the micro- and meso-level indicators, but there is no change at the macro level—meaning that the plan was applied correctly but it did not generate any impact—then the problem lies with the initial diagnostic. Most likely, a poor analysis was done of the different causal relationships that make up the problem, and therefore, despite completion of the program, no improvements were achieved. Alternatively, the problem may not lie with the diagnostic study but, rather, in the fact that some preconditions were not met or the context has changed since the policy was designed.

The indicators are a fundamental tool for monitoring and supervision but they present a series of theoretical and methodological obstacles. The former has to do with the conceptual richness of each right. Operationalization would require too many indicators, so it is necessary to limit the definition of the right to its basic content and select a reasonable number of indicators based on solid theoretical criteria. Along these lines, the UNHCHR (NACIONES UNIDAS, 2008) estimates that an average of four attributes can pull together, with a medium degree of precision, the essence of the normative content of each right. It is also important to build indices of indicators for each right, otherwise there would simply be long lists of indicators that, together, do not manage to tell us anything with respect to a specific object. Returning to the statement of Anaya Nuñoz (2008), defining an index leads to another difficulty: aggregation. Creating an index means adding up indicators defined by each component of each right. This entails determining whether all indicators have the same importance, so that they can be linearly aggregated or whether, in contrast, they should be assigned different weights.

Measuring the status of human rights presents one additional challenge. It requires dealing with subjective aspects, like an evaluation of the propriety of a law in light of international standards, the suitability of a public policy, the relevance of existing judicial resources, the recurrence of violations, etc. Typically, this information is not systematized much less codified. This information calls for special treatment, in order to be able to give it quantitative expression. These cases call for a rating system. By reviewing secondary sources (official reports, reports from autonomous human rights organizations, complaints and urgent actions presented by civil society organizations, etc.), a group of trained and qualified evaluators assesses and assigns points on an ordinal scale, thereby rating a given aspect of the right. The challenge here is to define the rating guidelines in a clear and transparent manner before the exercise begins in order to reduce the opportunities for subjectivity.24

The most relevant work done along these lines are the Freedom House and Terror Scale indices, which emphasize civil and political rights, and the index built by Cingranelli and Richards, which also includes some economic and social rights.

Once we have completed all of the steps above, we will have accomplished our task:

• We will have clearly “unpacked” the right; in other words, we will know the obligations and components that make up international human rights standards.

• Using tools like human rights plans and programs and the LFM, we will have been able to establish those international standards as goals and objectives of the public policy.

• We will have the necessary indicators to be able to evaluate the program in question, based on international human rights standards, at the micro-, meso-, and macro-levels.

• We will have evidence from an impact evaluation that tell us whether the policy is leading to an improvement in compliance with human rights or whether it is necessary to reformulate certain aspects of the structuring of the problem and the design of the policy.

1. It is important to stress that public policy is being studied here as a discipline—a body of theoretical/ analytical knowledge with practical applications whose primary aim is that of rationalizing public functions. In this sense, it is important to differentiate public policy analysis from public administration. The latter has been around longer and has different theoretical objectives.

2. Public policy analysis arrived in Mexico in the 1980s as a result of the serious economic crisis that Latin America suffered in those years, which obligated all countries to establish mechanisms to rationalize the use of increasingly scarce resources.

3. We refer here both to governmental bodies that compose the Executive, Legislative or Judicial branches, and those at the federal, local and municipal levels as well as independent institutions such as the Mexican National Bank, the Federal Institute For Access to Information and the Electoral Federal Institute.

4. It is important to distinguish between the public sphere and the public agenda. These are two different concepts. There may be issues that belong to the public sphere that are not necessarily part of the public agenda. The public sphere is one of social dialogue with multiple discursive nodes: the media, public plazas, collective interest, etc. However, there may be issues discussed in the public sphere that are not necessarily part of the government agenda. For an issue to become a public problem, it must be put on the public agenda and taken up by government offices so that it can motivate the analysis of public policy and jumpstart the public policy cycle.

5. Certainly the triumvirate formed in 1989 never stopped having serious tensions. Contradictions stemmed from the conflicts between ESCR and the neoliberal economic model during the 1990s and, in the first decade of the 21st century, the prioritization of the economic model over human rights. Worse, after the September 2001 attack on the twin towers in New York, democratically elected governments made security one of the key issues on their political agendas. Faced with the tension between many of the mechanisms that arise from security policy and those that stem from human rights, the former was given priority. Thus, the happy triumvirate of 1989 has disintegrated.

6. The political capacity of developing countries to “steer the boat” was also cast into doubt when they had to go up against greater economic powers, like large transnational corporations or other states that were defending the interests of their domestic companies. Furthermore, it is clear today that the market can be just as inefficient (and just as corrupt) as a state in the provision of public services.

7. Timeliness refers to the anticipated products of a public policy arriving at an appropriate time. For example, in the context of the right to health, if the medicine needed to cure an urgent illness arrives at the hospital a week after the patient dies, then the public policy was not timely.

8. The construction of the rights-holder can be seen in the history of constitutional movements. In the formulation of the Magna Carta of 1215, in the Petition of Rights and the Bill of Rights from the English Revolution in the 17th century, in the Declaration of Virginia from the American War for Independence, in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen of 1789, and in the French Constitution of 1791, we can see recognition of rights wrenched from political powers through insurrectionist social movements. The construction of the rightsholder can thus occur in the middle of conflict.

9. In English, the key concept for understanding this process of empowerment is the word rights-holder, which, literally translated into Spanish, would be derechohabiente. However, the word derechohabitante does not have the impact or the power that comes with being a rights-holder—the capacity of selfdetermination, the power to move from being a subject to being a citizen. The word “citizen” is also not the most apt, because it would leave out people who do not fulfill requirements for citizenship but that of course are still entitled to rights; this includes illegal immigrants, legal immigrants or residents, or children and adolescents that are not old enough to be considered full citizens. It seems that the best way to think about empowerment is through the concept of a rights-holder; however, the reader should keep in mind that this is not a legal term, but rather a political term. It not only deals with the legislative provision of a set of rights, but also the possibility and capacity to exercise powers that let one effectively exercise selfdetermination. It is not only about encapsulating rights within a law; it is also about establishing conditions for those rights to be exercised and for the individual to be empowered. On that point, the debates between Rawls, Dworkin and Amartya Sen on the theory of justice are fundamental to understanding the idea of primary goods, resources or capacities.

10. In the Inter-American human rights system, besides the Declaration there is also the American Convention on Human Rights (OAS, 1969) and its protocol on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, also known as the “Protocol of San Salvador” (OAS, 1988), the Inter-American Convention to Prevent and Punish Torture (OAS, 1985), the Inter-American Convention on the Forced Disappearance of Persons (OAS, 1994a), the Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment, and Eradication of Violence Against Women (OAS, 1994b), the Inter-American Convention for the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities (OAS, 1999), the Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights to Abolish the Death Penalty, the Inter- American Democratic Charter, and the Declaration of Principles on Freedom of Expression. In the United Nations human rights system, besides the Declaration there are various international human rights treaties, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (NACIONES UNIDAS, 2006a), the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (NACIONES UNIDAS, 1966); the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (NACIONES UNIDAS, 2005), the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (NACIONES UNIDAS, 1979), and the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families.

11. Many international human rights treaties under the United Nations have a committee that is in charge of monitoring compliance with the international obligations established in these treaties. Most do so through two mechanisms: reviewing reports presented by countries and reviewing the resolution of individual complaints presented by presumed victims of human rights violations in a particular country. In carrying out their responsibilities, these bodies issue resolutions that serve as inputs to identify the bounds of international human rights obligations.

12. There are three international, jurisdictional entities that cover human rights issues: the European Court of Human Rights, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, and the African Court of Human Rights. These bodies issue rulings as observations when there are requests from countries to clarify the interpretation and the scope of human rights obligations.

13. It should be noted that the theory of obligations under international human rights law is not only recent, but it is also still under construction. It is largely developed by human rights courts and tribunals and by United Nations Committees through their general observations. To the extent that the conceptualization and specification of international human rights obligations is done simultaneously by different entities, they are not given a single definition; rather, different conceptual advancements are made that have points of convergence and divergence. For example, in its General Observations, the ESCR Committee addresses the obligation to comply, which requires the State to adopt appropriate legislative, administrative, budgetary, judicial, or other measures with an eye to achieving full realization of rights. This obligation is subdivided into the obligations to facilitate, to guarantee, and to promote. The obligation to facilitate means that the State should adopt proactive measures to permit and help individuals and communities to enjoy their rights. The State is also obliged to guarantee a right whenever an individual or a group can not—for reasons other than their own willingness—put into practice a right for themselves using the resources at their disposition. The obligation to promote requires that the State must adopt measures to disseminate adequate information about the rights. The concepts laid out on the table are those determined to be most helpful for the purposes of this section.

14. Making amends implies restitution of the right where possible; for example, if the violation consisted of the illegal privation of someone’s liberty, restitution would mean setting the person free. Making amends also entails trying to compensate for both material and moral damages. Making amends often also means taking steps to guarantee that the violation will not happen again, building collective historical memory through the constructions of parks or commemorative monuments, or governments offering public recognition of the human rights violations along with an apology.

15. These cross-cutting principles were identified by the working group on methodology of the Coordinating Committee for the Development of a Human Rights Program in the Federal District of Mexico City; both authors participated actively in this working group.

16. The principles of equality and non-discrimination are included in almost all international human rights instruments. They are established in Articles 1 and 2 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (NACIONES UNIDAS, 1948); in Articles 1, 2, and 26 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (NACIONES UNIDAS, 2006a); in Articles 1 and 2 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights NACIONES UNIDAS, 1966); in Article 2 of the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man (OAS, 1948) and in Articles 1 and 24 of the American Convention on Human Rights (OAS, 1969). Two international conventions establish these principles even more specifically, namely the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (NACIONES UNIDAS, 2005) and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women NACIONES UNIDAS, 1979).

17. See, for example, Article 21 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (NACIONES UNIDAS, 1948), Article 25 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (NACIONES UNIDAS, 2006a) and Article 13.1 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (NACIONES UNIDAS, 1966).

18. See, for example, Articles 2, 5, 6, and 7 of International Labor Organization (ILO) Convention 169 concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries (OIT, 1989) and Articles 5, 18, 23, 27 and 43 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (NACIONES UNIDAS, 2007).

19. Abramovich (2006) alerts us to the practice of some countries in imposing limits on public demonstrations, thereby infringing on the rights to assembly and freedom of expression; he also recalls that the Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights affirmed that criminalization— understood to mean categorizing actions of social protest as criminal offenses—should only be used as a last resort, and only if a compelling public interest has been demonstrated.

20. For example, in the drafting of the Diagnóstico de Derechos Humanos del Distrito Federal (2007- 2008) (MÉXICO, 2008a) one of the rights under analysis was that of due process. One of the basic components of this right is that the person being subjected to a judicial process must have an interpreter. When trying to answer the question, “How many people need an interpreter in their legal cases and how many of them have had one?”, there was no data—official or unofficial—available, and so the status of this obligation could not even be studied.

21. The integration of a human rights perspective into the budget constitutes one of 16 recommendations in the Diagnóstico de Derechos Humanos del Distrito Federal (MÉXICO, 2008a). It is worth mentioning that the Coordinating Committee for the Development of the Diagnostic and Program in the Federal District of Mexico City, through its budgetary working group, played an important role in the promotion of and attention to this recommendation, by accompanying and advising the Federal District government, and especially the Finance Secretariat, in the first phase of this process, and by implementing a pilot project in 2008 and 2009 with the Federal District Health Secretariat, the Federal District Attorney General for Environment and Land Use Planning, and the Mexico City Water System.