The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities includes several sexuality-related rights. However, the sexuality-related rights in the Convention that was adopted are far less explicit and affirmative than those included in the initial draft text. This paper explores the reasons for these differences. First, the paper outlines the evolution of sexuality in disability theory and sexuality in international human rights debates. It then critically examines the discussions at the Ad Hoc Committee sessions where the Convention was elaborated. These discussions were marked by tensions between efforts to promote sexual rights and efforts to protect PWDs from unwanted sterilization and other forms of sexual abuse. Finally, the paper proposes ways of enhancing sexual rights claims for people with disabilities.

On May 3, 2008, the U.N. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities entered into force (UNITED NATIONS, 2011a). The first binding international instrument specific to people with disabilities (PWDs), the Convention elaborates how rights already enshrined in international rights law apply to PWDs, outlining domains where particular efforts are required.

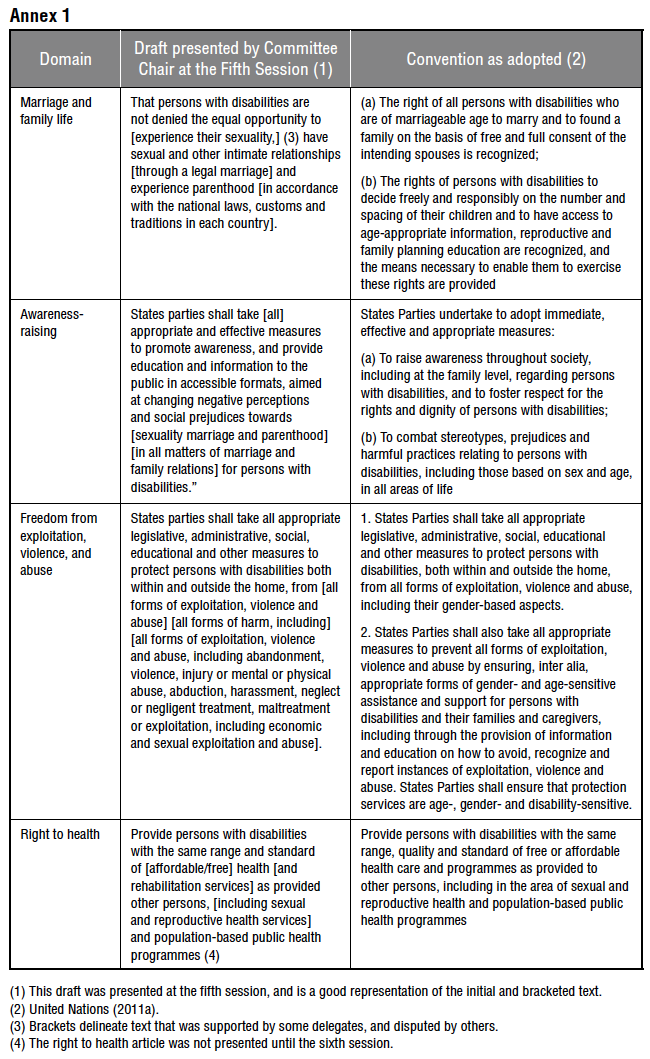

The Convention enumerates several rights that relate directly to sexuality, including the right to health; the right to liberty and security of person; freedom from exploitation, violence, and abuse; and respect for home and the family. It also contains an article specific to women with disabilities and an article mandating awareness-raising to combat stigma (UNITED NATIONS, 2006a). However, the sexuality-related rights in the Convention that was adopted are far less explicit and affirmative than those included in the initial draft, as shown in Annex 1.

What happened? As an example of what Michel Foucault called “put[ting] into discourse” (mise en discours) (FOUCAULT, 1984, p. 299) the Ad Hoc Committee negotiations illuminate prevailing views about disabled sexuality, as well as sexuality more broadly. While disability theorists and advocates increasingly proclaim the import of acknowledging and supporting disabled sexuality, the discourse produced by the Ad Hoc Committee reflects the ongoing salience of Foucault’s assertions that “abnormality” and sexuality are both subject to “governmentality” (FOUCAULT, 1984, p. 338).

Foucault described discourses as “polymorphous techniques of power” that “produce” effects of truth (FOUCAULT, 1984, p. 60, 298). In other words, the workings of power shape paradigms and social rules that frame the limits of human behavior and even reality. Such discourses need not be explicit; silences too hold power. “Silence itself – the things one declines to say or is forbidden to name…is less the absolute limit of discourse…than…an integral part of the strategies that underlie and permeate discourses” (FOUCAULT, 1984, p. 300). Thus, not acknowledging disabled sexuality is a way of regulating it.

As an attribute of the body that intersects with the control of the population, sexuality came to be a particular subject of governmentality in 19th century Western Europe. Sex “called for management procedures; it had to be taken charge of by analytical discourses” (FOUCAULT, 1984, p. 316, 307). The Church plays a particularly prominent role in Foucault’s analysis of discourse and sexuality; the “Christian pastoral also sought to produce specific effects on desire, by the mere fact of transforming it – fully and deliberately – into discourse: effects of mastery and detachment, to be sure, but also an effect of spiritual reconversion” (FOUCAULT, 1984, p. 306). Similarly, his concept of “bio-power” explains how the state, buttressed by scientific discourses, “brought life and its mechanisms into the realm of explicit calculations and made knowledge-power an agent of the transformation of human life” (FOUCAULT, 1984, p. 17).

Foucault’s insights regarding discourses, bio-power, and the role of the Church, shed light on evolutions in disability theory, as well as the negotiations regarding sexuality in the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

The broad term “disability” is employed throughout this paper. Although this term obscures heterogeneity, it reflects usage in many of the discourses this paper will examine. Where relevant, distinctions are made. The terms “disability studies” and “disability theory” refer to a self-described area of theoretical inquiry that is peopled by academics and advocates, many of whom have disabilities themselves. Much of their work expressly relates to both physical and mental disabilities. However, most of those theorists with disabilities have physical, as opposed to mental disabilities, and they thus focus much of their work on embodiment. Moreover, it is important to note that while the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities is a global treaty, much of the disability theory that is visible in the academy or on the internet was written by persons from the Global North. Voices from the South are rarely in evidence, particularly in the context of sexuality.

Sexuality was a peripheral topic in disability studies until about twenty years ago, and it continues to be under-addressed outside of disability studies, as well in social policies and programs (SHILDRICK, 2007; RICHARDSON, 2000; TEPPER, 2000). Historically and presently, there are two notable exceptions. Outside of the field of disability studies, sexuality is most frequently invoked: 1) When disabled sexuality is perceived as a threat to others through the purported expression of hyper-sexuality or aggression, or at least as a troubling attribute of individuals perceived (or forced) to be asexual (SHILDRICK, 2007; TEPPER, 2000; LEYDEN, 2007). 2) When PWDs, particularly women and children, are described as requiring special protection form sexual abuse or exploitation.

The perceived threat of disabled sexuality relates in part to its possible challenge of the monogamous, heterosexual, reproduction-oriented norm (TEPPER, 2000). Certain individuals are unable to experience “normal” sexuality, because of embodied difference, such as lack of genital sensation, infertility, or requiring a third person to facilitate intimate contact (SHILDRICK, 2009). Physically disabled male sexuality especially challenges normative discourses, as male sexuality is traditionally understood as a dominant, phallocentric experience (SHAKESPEARE, 1999). A man with a physical disability having sex is inconsistent with the gendered discourse of male virility (HAHN, 1994).

References to disabled women’s and children’s need for special protections from sexual abuse are certainly merited (FIDUCCIA; WOLFE, 1999; SHUTTLEWORTH, 2007). However, as one of the few visible discourses of disabled female sexuality, these references reinforce norms of both femininity and disability that describe women with disabilities (WWDs) as vulnerable, sexually passive or asexual, and dependent (SHAKESPEARE, 1999; LYDEN, 2007). Moreover, the sexual protection discourse is gendered; male vulnerability to sexual abuse is much less frequently invoked.

Concern about abuse and fear of disabled sexuality intersect in the control of reproduction. WWDs’ fertility is often proscribed through forced or coerced sterilization or abortion (GIAMI, 1998; EUROPEAN DISABILITY FORUM, 2009; UNITED NATIONS, 2009). This long-standing and widespread practice is frequently ostensibly performed to protect women from the pregnancy that may follow sexual abuse, or from the honor killing that could possibly follow pregnancy. In many countries, the law allows parents to subject a minor to this procedure without his/her consent (UNITED NATIONS, 1999, para. 447; NSW DISABILITY DISCRIMINATION LEGAL CENTRE, 2009; FIDUCCIA; WOLFE, 1999).

Disability theory (which is a fairly young field) has historically not addressed sexuality, except to selectively engage the issues noted above. Theorists and advocates countered the hegemonic discourse of hyper-sexuality, though they rarely engaged the canard of asexuality. They also sought to protect PWDs, particularly women, from forced or coerced sterilization or abortion (FIDUCCIA; WOLFE, 1999). Affirmative sexuality or sexual rights, however, were not in evidence. Silence may have persisted because sexuality was perceived as a desire, not a real need. Other advocacy priorities were more pressing (SHUTTLEWORTH, 2007; SHAKESPEARE, 2000). Moreover, sexuality had been an area of “distress, and exclusion, and self-doubt for so long, that it was sometimes easier not to consider it, than to engage with everything from which so many were excluded” (SHAKESPEARE, 2000, p. 160).

Over the past 20 years, this silence has been increasingly broken; theorists and activists make conscious efforts to undermine the power of discursive silence (TEPPER, 2000; SHUTTLEWORTH; MONA, 2000). Sexuality is more and more addressed in different theoretical strands of disability studies (RICHARDSON, 2000; TEPPER, 2000; SHUTTLEWORTH, 2007; FIDUCCIA; WOLFE, 1999). This change reflects broader trends in the emerging field of sexual rights, as well as growing recognition of the centrality of sexuality in the struggle for equality:

I’ve always assumed that the most urgent Disability civil rights campaigns are the ones we’re currently fighting for – employment, education, housing, transport, etc…For the first time now I’m beginning to believe that sexuality, the one area above all others to have been ignored, is at the absolute core of what we’re working for…. You can’t get closer to the essence of self or more ‘people-living-alongside-people’ than sexuality, can you?.

(as cited in: SHAKESPEARE, 2000, p. 165).

Informed in part by Foucault’s bio-power critique, disability theorists criticize what they refer to as the medical or individual model – a paradigm of disability that focuses on the individual body and the limitations imposed by physical or mental impairment. Social and programmatic manifestations of the medical model include physical rehabilitation and the primacy of professional (medical) power (SODER, 2009, p. 68). Locating harm in the discursive representations of disability as opposed to impairment itself, activists and theorists have sought to replace the medical model with the social model. The social model distinguishes between impairment and disability. Impairment is physical or mental dysfunction, whereas disability is the socially constructed assumption of incapacity that stems from an oppressive and discriminatory society (SHILDRICK, 2009; SODER, 2009; SHAKESPEARE, 1999; HAHN, 1994). In this conception, the social construction of disability underlies the stigma and harm that affects PWDs, not the impairments themselves.

However, in the past several years, some theorists have challenged the social model, arguing that it is hidebound and unduly dismissive of the importance of embodiment. These critiques are driven in part by the increasing attention to sexuality as well as to theoretical insights from feminism and queer theory. Some argue that the body should be ‘brought back’ into thinking about disability; impairment can restrict sexual engagement in a profound manner and this should be acknowledged and discussed (SODER, 2009; SHILDRICK, 2009). Dismissing the body at the expense of social analysis was, in the language of feminism, neglecting the relationship between the public and the private spheres (SHAKESPEARE, 1999).

This conceptual shift relates to the parallel development of notions of sexual citizenship, and its direct application to PWDs. Claims to sexual citizenship can crudely be grouped into two categories: 1) claims “for tolerance of diverse identities,” and, 2) “active cultivation and integration of these identities” (RICHARDSON, 2000, p. 122). This first category describes campaigns for self-definition and the right to exist as a minority. The second is broader, demanding the enabling conditions for sexual diversity and ‘sexual participation’ for previously stigmatized individuals and groups. Disability theorists and activists make such claims, with some asserting that the experience of pleasure is an accessibility issue (TEPPER, 2000; SHUTTLEWORTH, 2007). Sexual participation for PWDs may require moving beyond current prevailing conceptions of sexuality. Reflecting queer theory’s questioning of taxonomic understandings of sexuality, Tom Shakespeare, one of the most prolific theorists of disabled sexuality, asks: “Are we trying to win access for disabled people to mainstream sexuality or to change way sexuality is conceived?” (SHAKESPEARE, 2000, p. 163). Recognizing the importance of the body and making it the subject of sexual citizenship claims does not reinforce the medical approach to disability; it instead pushes current understandings of sexuality and sexual citizenship beyond current categories.

These theoretical evolutions are reflected in advocacy by organizations focused on disability rights as well as those concerned with sexual rights. For example, both the Irish Family Planning Association (IFPA) and the U.S.-based Center for Reproductive Rights (CRR) have recently issued relevant briefing papers: the IFPA’s on sexuality and disability and CRR’s on reproductive rights for women with disabilities (Irish Family Planning Association, no date; Center for Reproductive Rights, 2002). These efforts encompass physical and mental disabilities. The American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities recently stated that “people with mental retardation and related developmental disabilities, like all people, have inherent sexual rights and basic human needs” (as cited in: LYDEN, 2007, p. 4).

Advocacy has resulted in some policy changes. For example, in the Netherlands, Denmark, and parts of Australia, the use of trained sex workers and sexual surrogates is subsidized by the state (SHILDRICK, 2009, p. 61).

Conventions and declarations2are negotiated by member states of the United Nations, and individuals and NGOs may have the right to make proposals and express their opinion. The first UN human rights declaration, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and subsequent human rights treaties address several domains directly related to sexuality, including the role of the family, marriage, bodily integrity, and equality between the sexes (GIRARD, 2008). However, before 1993, the words “sexual” or “sexuality” had never appeared in an international intergovernmental document, except for an article in the Convention on the Rights of the Child providing for protection from sexual exploitation and abuse (PETCHESKY, 2000).

Sexuality was initially discussed in the context of reproductive health. Reproductive rights as such were not mentioned explicitly in a UN document until the 1968 International Human Rights Conference in Teheran (FREEDMAN; ISSACS, 1993), whose final act included a provision stating: “Parents have basic human rights to decide freely and responsibly on the number and spacing of their children” (UNITED NATIONS, 1968). The right of individual women (as opposed to parents) to decide on the number and spacing of their children was enshrined in the 1979 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (FREEDMAN; ISSACS, 1993). Advocates tried to broaden definitions of reproductive rights to include sexuality-related rights at the International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo in 1994, and the International Conference on Women in Beijing in 1995 (GIRARD, 2008). As a result of transnational advocacy and changing perceptions regarding women’s roles, among other factors, the final declarations of these two conferences represented a paradigm shift. Reproductive autonomy was recast as an objective, in contrast to earlier population control or pro-natalist orientations (GRUSKIN, 2008; GREER et al., 2009; GIRARD, 2008). The final declaration from the International Conference on Women stated:

the human rights of women include their right to have control over and decide freely and responsibly on matters related to their sexuality, including sexual and reproductive health, free of coercion, discrimination and violence. Equal relationships between women and men in matters of sexual relationships…require mutual respect, consent, and shared responsibility for sexual behavior and its consequences.

(UNITED NATIONS, 1995, para. 96)

Discussions about freedom from discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity have also begun in UN fora, although to date, there has been little mention of this in final documents.

Sexual and reproductive rights and non-discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation are increasingly included by advocates into the concept of sexual rights, which parallels the development of concepts of sexual citizenship. Sexual rights unites advocacy related to sexual violence against women; reproductive rights; lesbian, bisexual, gay, and transgender rights; and HIV/AIDS, among other areas (MILLER, 2009). However, the overriding concept of sexual rights remains insufficiently developed, with “predictable disjunctures” “constrain[ing] the evolution of coherent and progressive policy positions in this area” (MILLER, 2009, p. 1). Lack of coherence makes sexual rights–as well as the constituent elements that are grouped under this term – more vulnerable to powerful opposition.

Indeed, conservative forces pose many obstacles to the inclusion of sexual rights in UN documents. During negotiations, the Holy See has consistently proposed conservative definitions of family, and has sought to limit the de-coupling of women’s reproduction from the family unit (GIRARD, 2008). The Holy See and conservative allies (generally several Latin American and Islamic countries and allied NGOs) assert that sexual rights would undermine family relations and national, ethnic, or religious identities (KLUGMAN, 2000; FREEDMAN, 1995). In heated moments, delegates have declared that the term “sexual rights” implies promiscuity, and the right to have sex with whomever one wants to, including children and animals (KLUGMAN, 2000). The Holy See and others also claim that affirming sexual rights would represent the creation of new rights, as opposed to the application of human rights norms to the domain of sexuality. This argument is fairly weak, as one of the explicit objectives of Cairo, for example, was to apply human rights principles to reproduction – not to create ‘new rights’ (KLUGMAN, 2000).

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities was negotiated between 2002 and 2006. The Holy See and others demanded the same limitations on sexual rights as they had at earlier negotiations. However, these debates were at times qualitatively different than discussions in Cairo and Beijing. Widespread concern about eugenic measures and the centrality of the body in conceptions of disability shaped the debate.

President Vincente Fox of Mexico proposed a comprehensive treaty on the rights of people with disabilities at the 56th Session of the General Assembly in 2001 (UNITED NATIONS, 2003a). The treaty would be a binding follow-up to the Standard Rules on the Equalization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities, a resolution adopted by the General Assembly in 1993 (UNITED NATIONS, 1993). The treaty was negotiated in 7 sessions of an Ad Hoc Committee that was comprised of delegates from governments and NGOs holding consultative status with the UN’s Economic and Social Council. The initial draft texts were prepared by a Working Group, which was made up of 27 governments, 12 NGOs, and 1 national human rights institution representative.

The following discussion is based on a close reading of Ad Hoc Committee session summaries, country and NGO position papers, and draft text emerging from regional intergovernmental consultations. However, given the volume of documentation, a text search was employed to identify relevant text. The words “sex,” “repro,” “intimate,” “personal,” and “fertility” were searched. In addition, summaries of discussions around pertinent articles were read in their entirety, including the articles relating to marriage and family life; privacy; awareness-raising; health; and freedom from exploitation, violence, and abuse. Proposals regarding how to mainstream gender concerns were also read. Further underlining the point that disabled sexuality remains an under-addressed topic, no peer-reviewed or other papers relating to sexuality in the Convention were identified.

The discussion below is not an exhaustive analysis of the sexuality-related negotiations; abbreviated discussions about non-discrimination based on sexual orientation and other matters are not discussed. However, the discussion does speak to the most debated sexual rights issues.

Sexuality was mentioned in documents emanating from initial regional consultations almost exclusively in the context of sexual abuse and forced sterilization; indeed, sexual vulnerability was presented as a principal area for increased protections. For example, the introductory paragraph of a summary emerging from an expert meeting in Bangkok stated that “people with disabilities throughout the world are subjected to widespread violations of their human rights. These violations include malnutrition, forced sterilization, sexual exploitation…” (UNITED NATIONS, 2003b). NGO input had a similar focus. The first contribution from the World Network of Users and Survivors of Psychiatry regarding the article related to family life mentioned only the right to be free from sexual assault (in the realm of sexuality) (UNITED NATIONS, 2004d). Thirty-five participants from both governmental and non-governmental delegations presented a joint proposal in the first session regarding how to integrate “gender sensitive areas of concern.” Again, in relation to sexuality, they focused entirely on vulnerability to sexual assault. Indeed, other discussions regarding sexuality were rare in the first committee sessions. It did not emerge as a controversial issue until later in the negotiations.

References to sexual abuse in the Convention were uncontroversial, although they were not ultimately maintained in those terms. This was likely due in part to the semi-parallel discussions about the development of an article specific to women and children. Many of the same issues were covered in that draft text, though in somewhat different language. Moreover, forced sterilization, a widely shared priority, was addressed in the article relating to respect for home and the family. In any case, as will be shown, the concept of protection was a leitmotif of the sexuality-related negotiations; some delegates invoked the need for protection in their opposition to any mention of sexuality.

The initial draft text developed by the Working Group included a “right to sexual and reproductive health services.” This language derived in part from the Standard Rules, which stipulated that “Persons with disabilities must have the same access as others to family-planning methods, as well as to information in accessible form on the sexual functioning of their bodies (UNITED NATIONS, 2003a).

The Holy See objected to the term “sexual and reproductive health services” from the moment it was introduced (UNITED NATIONS, 2004b). NGO responses were slower. The Committee Chair solicited NGO input on the day the draft text was introduced. Several agencies commented, including Rehabilitation International, the World Network of Users and Survivors of Psychiatry, Handicap International, Save the Children, WHO, and a consortium of national human rights institutions. They did not mention sexual and reproductive health services. Only one NGO commented on this aspect – National Right to Life. They stated that explicitly mentioning sexual and reproductive health would necessarily limit the scope of the right to health, and would “promote the use of genetic testing to abort unborn babies with disabilities.” In its place, they proposed text proscribing the “denial of medical treatment, foods or fluids” (UNITED NATIONS, 2004b).

NGOs that were not part of the pro-life alliance were evidently ill-prepared to engage the debate. They did advocate for maintaining the text in later sessions, although not extensively, and they clearly lacked the organization of the right to life coalition. Indeed, the right to life message coalesced in later sessions, with numerous NGOs opining that the phrase might codify “abortion and euthanasia,” including of newborn babies, and several linking the discussion to denial of food and water for PWDs (UNITED NATIONS, 2005d). Governmental delegations also made this argument, though they discussed only abortion, not euthanasia. Qatar, Iran, Kenya, Jamaica, Yemen, Syria, Pakistan, Sudan, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates all urged cutting the text, alleging that it would create a new right, including potentially a right to abortion. The word “services,” in particular was alleged to be code for including abortion (UNITED NATIONS, 2005b, 2005d, 2006c). The U.S. too supported the deletion of the text on the grounds that including it would somehow endanger PWDs, explaining that it supported deletion of the text because of the history of forced sterilization of PWDs in the United States (UNITED NATIONS, 2006d).

Several NGOs that were not physically present at the negotiations submitted comments stating that maintaining the text was important. They argued primarily that specifically mentioning sexual and reproductive health was important because PWDs often lacked access due to persistent perceptions that they were asexual (UNITED NATIONS, 2005a, 2006c). Several country delegations came out in favor of the text at the seventh session, including Brazil, Canada, Croatia, Ethiopia, Mali, Norway, Uganda, and the European Union (EU) (UNITED NATIONS, 2006d). The EU stated that sexual and reproductive health services do not include abortion, an assertion that the Council of Europe, WHO, and the Special Rapporteur on the Right to Health supported in written submissions (UNITED NATIONS, 2006d, 2006e). Delegates grew frustrated with the stagnant debate, and the Chair atypically intervened to state that sexual and reproductive health services do not include abortion, and that the phrase “health services” appears in both the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families and CEDAW (UNITED NATIONS, 2006e).

Uruguay and Costa Rica and later several other countries eventually united around a proposal to maintain the phrase “sexual and reproductive” but to cut the term “services.” This is the language that was ultimately adopted (UNITED NATIONS, 2006d). Despite this compromise, several countries signed the treaty with relevant reservations. El Salvador stipulated that it signed the convention insofar as it did not violate the constitution of El Salvador (UNITED NATIONS, 2011b), which stipulates that life begins at conception (CENTER FOR REPRODUCTIVE RIGHTS, 2003). Several EU countries formally indicated their opposition to El Salvador’s reservation. Malta made the following interpretive statement: “Malta understands that the phrase ‘sexual and reproductive health’ in Art 25 (a) of the Convention does not constitute recognition of any new international law obligation, does not create any abortion rights, and cannot be interpreted to constitute support, endorsement, or promotion of abortion” (UNITED NATIONS, 2011b). Monaco and Poland made very similar interpretive statements (UNITED NATIONS, 2011b).

The sexuality-related debate in regards to these articles was even more contentious and moribund than the right to health negotiations. As can be seen in Annex 1, the initial text for both of these articles made several references to sexuality. Again, the proposed text was close to the Standard Rules, which specify:

• States should promote the full participation of persons with disabilities in family life. They should promote their right to personal integrity and ensure that laws do not discriminate against persons with disabilities with respect to sexual relationships, marriage and parenthood.

• Persons with disabilities must not be denied the opportunity to experience their sexuality, have sexual relationships and experience parenthood.

• States should promote measures to change negative attitudes towards marriage, sexuality and parenthood of persons with disabilities, especially of girls and women with disabilities, which still prevail in society (UNITED NATIONS, 2003a).

In the initial debate, several countries, namely Libya, Syria, Qatar, Iran, and Saudi Arabia urged sublimating sexuality-related rights to marriage and/or traditional norms or laws (UNITED NATIONS, 2004a). However, these delegates were not uniformly opposed to the mention of sexuality; several suggested rewordings that included the term (UNITED NATIONS, 2004a). Saudi Arabia, for example, explicitly stated that they accepted the term, but only with a marriage caveat (UNITED NATIONS, 2004a). For their part, the Holy See and Yemen were opposed to the term with or without any caveats (UNITED NATIONS, 2004a, 2004b).

The allegation that these draft articles, particularly the phrase “experience their sexuality,” would amount to the elaboration of new rights was frequently made. The Holy See repeatedly stated that the language in both articles did not appear in any other convention, neglecting to acknowledge that it did appear in the non-binding Standard Rules (UNITED NATIONS, 2004b, 2004e). Holy See-aligned NGOs again supported this position, with the Society of Catholic Social Scientists and the Pro-Life Family Coalition contending that mentioning sexual relationships out of the context of marriage would mean that the CRPD went into “uncharted and controversial directions” (UNITED NATIONS, 2004b).

As in the case of the sexual and reproductive health negotiations, opposition to the Holy See was somewhat slow in coming. Norway reacted initially (UNITED NATIONS, 2004b), but the EU, Australia, Brazil, Childe, and New Zealand did not express their desire to maintain at least some of the language until days later on in the session or the next session (UNITED NATIONS, 2005c, 2006d).

Several compromises were proposed. The Canadian delegation acknowledged that it was not “aware of a right to sexuality per se,” but unequivocally stated that they were opposed to the Holy See suggestions to exclude references to sexuality, as well as efforts by “Syria, Qatar, Libya, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen to roll back language on sexuality through references to marriage or religious and social conventions” (UNITED NATIONS, 2004e). The Canadian delegation suggested framing sexuality-related rights in the context of non-discrimination, specifying that PWDs had the right to enjoy these rights “on an equal footing” (UNITED NATIONS, 2004f). Several countries supported this proposal, including Costa Rica, Morocco, and New Zealand (UNITED NATIONS, 2004e, 2004f). Other delegates suggested different compromises, including replacing the term “sexual” with “intimate,” replacing the term “sexuality” with “sexual life,” or keeping some or all of the sexuality language but accepting the marriage caveat (UNITED NATIONS, 2004a). The Holy See, Yemen, Syria, and Qatar rejected these compromises.

NGO advocacy to maintain the sexuality language was also not immediate. With the exception of the pro-life groups, no NGO mentioned it during the initial comment period on the draft article (UNITED NATIONS, 2004b). Only one explicitly addressed sexuality; Disabled Peoples’ International spoke of the centrality of “intimate relationships” (UNITED NATIONS, 2004e). NGOs who were not present later submitted written contributions in support of language related to sexuality. A coalition of individuals and agencies from Eastern Europe noted laws should not discriminate “against persons with disabilities with respect to sexual relationships, marriage and parenthood. Persons with disabilities should be enabled to live with their families and must have the same access as others to family-planning methods, as well as to appropriately designed and accessible information on sex and sexuality” (UNITED NATIONS, 2004c). The World Network of Users and Survivors of Psychiatry maintained that the Convention needed “to address this issue [sexuality] even if it was not a right, as deprivation of this choice happens in instances of adults living in institutions” (UNITED NATIONS, 2004f).

Additional written contributions during the seventh session were even more unequivocal. The Japan Disability Forum and the International Disability Caucus both explained that they supported the articulated sexual rights because of the longstanding prejudice against sexual relationships of PWDs and the negative legacy of eugenics (UNITED NATIONS, 2004g). For them, the legacy of eugenics did not mean that references to sexuality were threatening, but rather that articulating sexual rights was vital to promoting autonomy and citizenship.

As in the case of the sexual and reproductive health debate, several countries with predominantly Muslim populations hardened their positions to converge with that of the Holy See. Nigeria, Qatar and Yemen eventually urged the deletion of all the text mentioning sexuality (UNITED NATIONS, 2006d). Other countries suggested deleting the text without explaining why, including Russia and China (UNITED NATIONS, 2006d). Japan recommended more general text to “avoid over-prescriptive, controversial language to many countries,” a position India supported (UNITED NATIONS, 2004h).

As debate dragged on, the Chair intervened. Noting that the word “sexuality” is particularly difficult for some countries, he explained that delegates did not intend to force cultures to any particular position. He went on to say that it may be the first time that sexual relationships are addressed in a U.N. convention, and suggested language from the Standard Rules as a guide (UNITED NATIONS, 2005c). Opposition persisted. Citing the “numerous cultural concerns about the word sexuality,” the Chair removed it at the seventh session (UNITED NATIONS, 2006d).

Forced sterilization was also included in the discussions regarding marriage and family life. As noted, as a violation of the right of bodily integrity of PWDs, forced sterilization was a widely shared priority. Despite the fact that the right to decide on the number of spacing of one’s children implied the right to be free from forced sterilization, many countries, including Australia, China, Costa Rica, the EU, Kenya, Mexico, New Zealand, Serbia and Montenegro, Thailand, Uganda, Thailand, and the United States suggested the forced sterilization be explicitly mentioned in the Convention (UNITED NATIONS, 2004a). Many NGOs also advocated for the Convention to directly address sterilization, including by prohibiting laws that allow parents to subject their minor children to sterilization (UNITED NATIONS, 2005d, 2006c). New Zealand suggested the more positive and uncontroversial wording that was ultimately retained, affirming that PWDs have the right to “retain their fertility” (UNITED NATIONS, 2004a).

The false distinction between negative rights (freedom from) and positive rights (freedom to) is not unique to disability rights, but the context of particular concern about sexual abuse and eugenic measures is unique.

Throughout the Convention negotiations, considerable tension existed between efforts to promote sexual rights and efforts to protect PWDs from unwanted sterilization. This was complicated by repeated attempts to elevate the fetus to a being with rights, making a non-discrimination approach to disabled sexuality infeasible. The Holy See and their allies pushed the discussion to be about how to apply existing human rights norms to fetuses with abnormalities, rather than how to apply these norms to disabled sexuality. They further posited that access to reproductive and sexual health services would somehow lead to purposeful deprivation of food and water for adults with disabilities, or murder of newborn children with disabilities. This concern was alluded to only twice in the hundreds and hundreds of DPO statements. It was an intellectually flawed, but somewhat successful attempt to establish a slippery slope from abortion to euthanasia of the very kind of individuals attending the negotiations. As a result, protectionist measures were maintained and affirmations of sexual rights were eliminated. Discursive silences about disabled sexuality were enshrined in the most important official expression of global disability discourse.

As in Foucault’s description of 19th century Europe, the Church (the Holy See) was instrumental in delineating the boundaries of acceptable sexuality and in protecting those lacking ‘reason’ from the desires in their own bodies. Several states allied themselves with the Holy See, expressing the need to police “rampant sex” (UNITED NATIONS, 2005c) and restrict reproductive autonomy.

The delay in response and the lack of vigorous advocacy for sexual rights indicates that DPOs continue to be reluctant to engage sexuality. Moreover, they were likely unprepared, not anticipating a coalition of Holy-See aligned organizations with a pre-planned agenda. Indeed, of the civil society groups present at the negotiations, all were DPOs, with the exception of the Catholic right to life groups and Save the Children. The right to life groups were ready to advocate from the moment discussion was allowed; the DPOs were not.

Enhancing DPO sexual rights advocacy capacity (assuming they would want this) would facilitate future discussions regarding the Convention treaty body and other international negotiations. DPOs are already moving in this direction. In November 2010, the UN Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights held a day of general discussion on “the right to sexual and reproductive health.” Two of the 15 written submissions were from DPOs (UNITED NATIONS, 2010).

Similarly, ensuring that sexual and reproductive rights organizations contribute to disability-related debates would further erode taboos around disabled sexuality. Indeed, further integration of disability into sexual rights advocacy would be an important manifestation of the intent of the Convention – ensuring the application of human rights norms to PWDs.

As the workings of power are diffuse, so too should our advocacy come from multiple directions. Sexual rights as a rubric of rights’ claiming will likely continue to grow, providing greater and better opportunities to move beyond current understandings of sexual citizenship to include disabled and all other bodies.

1. The term “international law” is used in this paper to refer to U.N. declarations and conventions, not to those associated with regional mechanisms.

2. Conventions are binding, whereas declarations are not. However, declarations do represent a consensus, and overtime, they can come to be considered binding (as customary international law). Moreover, as in the case of the CRPD, elements of Declarations can become the basis for a binding convention.

Bibliography and other sources

CENTER FOR REPRODUCTIVE RIGHTS. 2002. Reproductive rights and women with disabilities: a human rights framework. Available at: http://www.handicap-international.fr/bibliographie-handicap/4PolitiqueHandicap/groupes_particuliers/Femmes_Genre/reproductive_rights.pdf . Last accessed on: 12 Nov. 2010.

______. 2003. Supplementary information on El Salvador scheduled for review by the UN Human Rights Committee during its seventy-eighth session. Available at: http://reproductiverights.org/sites/crr.civicactions.net/files/documents/sl_ElSalvador_2003.pdf . Last accessed on: 19 Dec. 1010.

EUROPEAN DISABILITY FORUM. 2009. Violence against women: Forced sterilization of women with disabilities is a reality in Europe. Available at: http://www.edf-feph.org/Page_Generale.asp?DocID=13855&thebloc=23097 . Last accessed on: 2 Dec. 2010.

FIDUCCIA, B.W. 2000. Current issues in sexuality and the disability movement. Sexuality and disability, v. 18, n. 3. P. 167-174, Sept.

FIDUCCIA, B.W.; WOLFE, L.R. 1999. Women and girls with disabilities, defining the issues, an overview. Washington D.C., Center for Women Policy Studies & Women and Philanthropy.

FOUCAULT, M. 1984. The Foucault reader. New York: Pantheon Books.

FREEDMAN L. 1995. Reflections on emerging frameworks of health and human rights. Health and Human Rights, Cambridge, v. 1, n. 4, p. 315-348, Dec.

FREEDMAN, L.P.; ISSACS, S.L. 1993. Human rights and reproductive choice. Studies in Family Planning, Malden, v. 24, n. 1, p. 18-30, Jan.-Feb.

GIAMI, A. 1998. Sterilisation and sexuality in the mentally handicapped. European Psychiatry, v. 13, n. S3, p. 113s-119s.

GIRARD, F. 2008. Negotiating sexual rights and sexual orientation at the U.N. In: PARKER, R.; PETCHESKY, R.; SEMBER, R. (Ed.). Sex politics: reports from the frontlines. Available at: http://www.sxpolitics.org/frontlines/book/pdf/sexpolitics.pdf . Last accessed on: 30 Nov. 2010.

GREER G. et al. 2009. Sex, rights and politics – from Cairo to Berlin. The Lancet, v. 374, n. 9691, p. 674-675, Aug.

GRUSKIN, S. 2000. The conceptual and practical implications of reproductive and sexual rights: How far have we come? Health and Human Rights, Cambridge, v. 4, n. 2, p. 1-6.

______. 2008. Reproductive and sexual rights: do words matter? American Journal of Public Health, v. 98, n. 101, p. 1737, Oct.

HAHN, H. 1994. Feminist perspectives, disability, sexuality and law: new issues and agendas. 4 Southern California review of law and women’s studies, v.97, n. 105.

IRISH FAMILY PLANNING ASSOCIATION (IFPA). 2010. Sexuality and disability. Dublin: Irish Family Planning Association. Available at: http://ifpa.ie/Media-Info-Centre/Publications/Publications-Reports/Sexuality-and-Disability . Last accessed on: 25 Nov. 2010.

KLUGMAN, B. 2000. Sexual rights in Southern Africa: A Beijing discourse or a strategic necessity? Health and Human Rights, Cambridge, v. 4, n. 2, p. 145-173.

LYDEN, M. 2007. Assessment of sexual consent capacity. Sexuality and disability, v. 25, n. 1, p. 3-20, March.

MILLER, A. 2009. Sexuality and human rights: discussion paper. Geneva: International Council on Human Rights Policy. Available at: http://www.ichrp.org/files/reports/47/137_web.pdf . Last accessed on: 14 Nov. 2010.

NSW DISABILITY DISCRIMINATION LEGAL CENTRE. 2009. Submission: ‘Article 12 of the CRPD- the right to equal recognition before the law.’ Available at: www2.ohchr.org/SPdocs/CRPD/…/Article12NatlAssoCommLegal.doc . Last accessed on: 2 Dec. 2010.

PETCHESKY, R. 2000. Sexual rights: inventing a concept, mapping an international practice. In: PARKER, R. (Ed.). Framing the sexual subject: The politics of gender, sexuality and power. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 81-103.

RICHARDSON, D. 2000. Constructing sexual citizenship: theorizing sexual rights. Critical Social Policy, v. 20, n. 1, p. 105-135, Feb.

SHAKESPEARE, T. 1999. The sexual politics of disabled masculinity. Sexuality and disability, v. 17, n. 1, p. 53-64, Jan.

______. 2000. Disabled sexuality: toward rights and recognition. Sexuality and disability, v. 18, n. 3, p. 159-166, Sept.

SHILDRICK, M. 2007. Contested pleasures: the sociopolitical economy of disability and sexuality. Sexuality research and social policy, v. 4, n. 1, p. 53-66, Mar.

______. 2009. Dangerous discourses of disability, subjectivity and sexuality. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

SHUTTLEWORTH, R. 2007. Critical research and policy debates in disability and sexuality studies. Sexuality research and social policy, v. 4, n. 1, p. 1-14, Mar.

SHUTTLEWORTH, R.; MONA, L.R. 2000. Introduction to the special issue. Sexuality and disability, v. 18, n. 4, p. 229-231, Dec.

SODER, M. 2009. Tensions, perspectives, and themes in disability studies. Scandinavian journal of disability research, v. 11, n. 2, p. 67-81.

TEPPER, M.S. 2000. Sexuality and disability: the missing discourse on pleasure. Sexuality and disability, v. 18, n. 4, p. 283-290, Dec.

UNITED NATIONS. 1968. Final act of the international conference on human rights. A/CONF.32/41. Available at: http://untreaty.un.org/cod/avl/pdf/ha/fatchr/Final_Act_of_TehranConf.pdf . Last accessed on: 1 July 2010.

UNITED NATIONS. 1993. Secretary General. Issues and emerging trends related to advancement of persons with disabilities. Available at: http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/rights/a_ac265_2003/ie.htm . Last accessed on: 17 Nov. 2010.

______. 1995. Fourth World Conference on Women. Platform for Action of the Fourth World Conference on Women, UN Doc. A/CONF.177/20, Sept. Available at: http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/beijing/pdf/BDPfA%20E.pdf . Last accessed on: 28 Feb. 2011.

______. 2000. The Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC). Report of the Committee on the Rights of the Child. General Assembly fifty-fifth session, UN Doc. A/55/41, 8 May 2000. Available at: http://www.un.org/documents/ga/docs/55/a5541.pdf . Last accessed on: 28 Feb. 2011.

______. 2003a. General Assembly. Standard Rules on the Equalization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities, UN Doc. A/RES/48/96, 48th Session. Available at: http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/dissre00.htm . Last accessed on: 25 Feb. 2011.

______. 2003b. Ad Hoc Committee on a Comprehensive and Integral International Convention on Protection and Promotion of the Rights and Dignity of Persons with Disabilities. Bangkok recommendations on the elaboration of a comprehensive and integral international convention to promote and protect the rights and dignity of persons with disabilities, UN Doc. A/AC.265/2003/CRP/10. Available at: http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/rights/a_ac265_2003_crp10.htm . Last accessed on: 25 Feb. 2011.

______. 2004a. Ad Hoc Committee on a Comprehensive and Integral International Convention on Protection and Promotion of the Rights and Dignity of Persons with Disabilities. Report of the third session of the Ad Hoc Committee on a comprehensive and integral international convention on the protection and promotion of the rights and dignity of persons with disabilities, A/AC.265/2004/5. Available at: http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/rights/ahc3reporte.htm . Last accessed on: 26 Feb. 2011.

______. 2004b. Ad Hoc Committee on Comprehensive and Integral International Convention on Protection and Promotion of the Rights and Dignity of Persons with Disabilities. Daily summary of discussions related to Article 21right to health and rehabilitation. Available at: http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/rights/ahc3sum21.htm . Last accessed on: 26 Feb. 2011.

______. 2004c. Ad Hoc Committee on Comprehensive and Integral International Convention on Protection and Promotion of the Rights and Dignity of Persons with Disabilities. Working group: compilation of elements, coalition of individuals, organizations and agencies of the people, for the people and by the people with disabilities in Eastern Europe. Available at: http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/rights/wgcontrib-EastEurope.htm . Last accessed on: 26 Feb. 2011.

______. 2004d. Ad Hoc Committee on Comprehensive and Integral International Convention on Protection and Promotion of the Rights and Dignity of Persons with Disabilities. Working group: compilation of elements, World Network of Users and Survivors of Psychiatry, Available at: http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/rights/wgcontrib-wnusp.htm . Last accessed on: 25 Feb. 2011.

______. 2004e. Ad Hoc Committee on a Comprehensive and Integral International Convention on Protection and Promotion of the Rights and Dignity of Persons with Disabilities. Daily summary of discussions related to Article 14, respect for privacy, the home and the family. Available at: http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/rights/ahc3sum14.htm . Last accessed on: 27 Feb. 2011.

______. 2004f. Ad Hoc Committee on a Comprehensive and Integral International Convention on Protection and Promotion of the Rights and Dignity of Persons with Disabilities. Daily Summary related to Draft Article 14, respect for privacy, the home and the family. Available at: http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/rights/wgsuma14.htm . Last accessed on: 27 Feb. 2011.

______. 2004g. Ad Hoc Committee on a Comprehensive and Integral International Convention on Protection and Promotion of the Rights and Dignity of Persons with Disabilities. NGO comments on the draft text. Available at: http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/rights/ahc8contngos.htm . Last accessed on: 27 Feb. 2011.

______. 2004h. Ad Hoc Committee on a Comprehensive and Integral International Convention on Protection and Promotion of the Rights and Dignity of Persons with Disabilities. Comments, proposals and amendments submitted electronically, Article 22 Respect for privacy, home and the family. Available at: http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/rights/ahcstata22fscomments.htm . Last accessed on: 27 Feb. 2011.

______. 2005a. Ad Hoc Committee on a Comprehensive and Integral International Convention on Protection and Promotion of the Rights and Dignity of Persons with Disabilities. International Disability and Development Consortium Reflection Paper, contribution to the 5th session of the Ad Hoc Committee. Available at: http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/rights/ahc5contngos.htm . Last accessed on: 26 Feb. 2011.

______. 2005b. Ad Hoc Committee on a Comprehensive and Integral International Convention on Protection and Promotion of the Rights and Dignity of Persons with Disabilities. Daily summary of the fifth session, 25 January 2005. Available at: http://www.u.org/esa/socdev/enable/rights/ahc5sum25jan.htm . Last accessed on: 25 Feb. 2011.

______. 2005c. Ad Hoc Committee on a Comprehensive and Integral International Convention on Protection and Promotion of the Rights and Dignity of Persons with Disabilities. Daily summary of the fifth session, 2 February 2005. Available at: http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/rights/ahc5sum2feb.htm . Last accessed on: 25 February 2011.

______. 2005d. Ad Hoc Committee on a Comprehensive and Integral International Convention on Protection and Promotion of the Rights and Dignity of Persons with Disabilities. Daily summary of discussion at the sixth session, 8 August 2005. Available at: http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/rights/ahc6sum8aug.htm . Last accessed on: 22 Feb. 2011.

______. 2006a. General Assembly. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and Optional Protocol. Available at: http://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convoptprot-e.pdf . Last accessed on: 28 Feb. 2011.

______. 2006b. Ad Hoc Committee on a Comprehensive and Integral International Convention on Protection and Promotion of the Rights and Dignity of Persons with Disabilities. Report of the Ad Hoc Committee on a Comprehensive and Integral International Convention on Protection and Promotion of the Rights and Dignity of Persons with Disabilities on its seventh session. Available at: http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/rights/ach7report-e.htm . Last accessed on: 28 Feb. 2011.

______. 2006c. Ad Hoc Committee on a Comprehensive and Integral International Convention on Protection and Promotion of the Rights and Dignity of Persons with Disabilities. Comments, proposals, and amendments submitted electronically, seventh session. Available at: http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/rights/ahcstata25sevscomments.htm . Last accessed on: 25 Feb. 2011.

______. 2006d. Ad Hoc Committee on a Comprehensive and Integral International Convention on Protection and Promotion of the Rights and Dignity of Persons with Disabilities. Daily summary of discussion at the seventh session, 24 January 2006. Available at: http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/rights/ahc7sum24jan.htm . Last accessed on: 27 Feb. 2011.

______. 2006e. Ad Hoc Committee on a Comprehensive and Integral International Convention on Protection and Promotion of the Rights and Dignity of Persons with Disabilities. Daily summary of discussion at the seventh session, 25 January 2006. Available at: http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/rights/ahc8gpcart25.htm . Last accessed on: 27 Feb. 2011.

______. 2009. Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health to the UNGA, UN Doc., A/64/272, 64th session.

______. 2010. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). Day of general discussion on ‘the right to sexual and reproductive health’. Available at: http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/cescr/discussion15112010WrittenContr.htm#experts . Last accessed in: 20 Dec. 2010.

______. 2011a. Enable. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Available at: http://www.un.org/disabilities/default.asp?navid=13&pid=150 . Last accessed on: 27 Feb. 2011.

______. 2011b. Enable. Declarations and reservations to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Available at: http://www.un.org/disabilities/default.asp?id=475 . Last accessed on: 28 Feb. 2011.