This article provides a non-exhaustive overview of Brazil’s international activities in the field of public health, in order to determine whether the country actually has a foreign policy in health per se. The first part of the text aims to distinguish Brazilian cooperation from what is practiced by the developed world, by giving a brief review of South-South cooperation in health, with a special emphasis on the Community of Portuguese-Speaking Countries (CPLP) and the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR). The second part of the text is devoted to Brazilian action in multilateral fora, where the country has proposed a “new governance” of global health. The article concludes that a Brazilian foreign policy does indeed exist in the field of public health and that the tensions found therein are cross-cutting, encompassing the internal and external spheres. Its future depends on the arbitration of numerous contradictions, using as a reference the principles of the Brazilian public health system, known as the Unified Health System (SUS).

Health first became a challenge for diplomacy around the time of the first International Sanitary Conference, held in 1851, in Paris. The conference, however, was not concerned with the health of populations: the real objective of the meeting was the need to reduce the duration of quarantine requirements, which were considered excessive and harmful to commerce (KEROUEDAN, 2013a, p. 28). Consequently, the tension between health and commerce, between human and economic interests, between science and profit, is “constitutive of the paradox of international health” (KEROUEDAN, 2013b, p. 1).

Since then, international health has undergone an extraordinary evolution whose pinnacle was the creation of the World Health Organization (WHO), in 1946, as the “directing and coordinating authority on international health work” (ORGANIZAÇÃO MUNDIAL DA SAÚDE, 1946). Nevertheless, criticized for its eminently scientific and technical character (GOSTIN, 2007, p. 226), the WHO has been overshadowed in recent decades by the prominence of powerful institutions in the financing of international projects, notably the World Bank and other private and philanthropic agencies. Moreover, the influenza A (H1N1) pandemic, in 2009 and 2010, raised doubts about the independence of the WHO in relation to the pharmaceutical industry (VENTURA, 2013).

A key point in the evolution of international health was the outbreak of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, which not only gave rise to a new type of transnational activism in support of access to treatment, but also influenced research and science, clinical practices, public policies and social behavior (BRANDT, 2013). Meanwhile, the fear of bioterrorism has elevated public health into the realm of international security, under the leadership of the United States, for which the concept of national security includes the field of public health (ZYLBERMAN, 2013, p. 126).

In other words, health has gained ground on the agenda of numerous fora, namely the United Nations Security Council, the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the alliances between developed countries, such as the Group of Eight (G8), and between emerging countries, such as the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa).

The expression “international health” has gradually been replaced by the controversial and polysemic term “global health”. While the former is generally used to refer to agreements and cooperation projects between States, the latter encompasses new actors and innovative topics. There is also more widespread use of the expression “global health diplomacy”, which consists of public health negotiations across borders and in health fora and other similar areas, global health governance, foreign policy and health, and the development of national and global health strategies (KICKBUSH; BERGER, 2010, p. 20).

Many doubts surround these new concepts. Three billion human beings – nearly half the population of the planet – still live in perilous sanitary conditions, frequently aggravated by a situation of extreme poverty (KOURISLSKY, 2011, p. 15). Are we dealing, therefore, with naively descriptive slogans that attempt to stress the similarity of problems and solutions that transcend borders, or with a North American or Eurocentric hegemonic universalism that promotes the dissemination of goods, technology and financial products beyond its own internal security? (BIRN, 2012, p. 101). Dominique Kerouedan warns of the risk that our culture of public health and development cooperation may be taken over by the dominant notion of global health, or the Global South, which she considers relatively unresponsive to the real local concerns of poorer countries (KEROUEDAN, 2013a, p. 22).

But what does Brazil have to say about global health? This article proposes to provide an overview (that is, therefore, not exhaustive) of Brazil’s international actions in the field of public health. Does Brazil even have a foreign policy in health?

There is no doubt that Brazil’s position in relation to the global governance of intellectual property is directly related to its response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic (SOUZA, 2012, p. 204). Neither is there any doubt that, since 2003, with the rise of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva to power, Brazil gave a new boost to South-South cooperation – between developing countries – exploring, among other things, the potential of health as a social topic at the heart of foreign policy (PEREZ, 2012, p. 79). Expressions such as “prestige diplomacy” or “soft imperialism” began to be used to identify this period of Brazilian foreign policy (VISENTINI, 2010).

Much of the criticism levelled at this foreign policy is due to the fact that our diplomacy sought to reconcile two largely incompatible identities (LIMA, 2005): one of a country dissatisfied with the global order, a skillful mediator of the interests of countries from the South in multilateral and regional spheres; and one of a major emerging market, eager to receive international investments and stage global events. At the same time, Brazil became an international benchmark on the subject of combating poverty.

According to the official discourse, Brazilian technical cooperation is demand-driven and governed by the principles of solidarity diplomacy, the recognition of local experience, the non-imposition of conditionalities, non-interference in the internal affairs of the partner countries and unbounded by commercial interests or profit seeking (LEITE et al, 2013). The expression solidarity diplomacy emerged primarily after Brazil assumed unprecedented responsibilities in relation to Haiti (SEITENFUS, 2006).

The first part of this article aims to distinguish Brazilian health cooperation from what is practiced by the developed world. A brief review of South-South cooperation shall be presented, with special attention paid to the Community of Portuguese-Speaking Countries (CPLP) and the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR). The second part of the text is devoted to Brazilian action in multilateral fora, where Brazil has proposed a “new governance” of global health. The article concludes that Brazil does indeed have a solidary foreign policy in the field of public health, whose future depends on overcoming limits and contradictions that result from cross-cutting tensions, with internal and external interfaces.

For the purposes of this article, foreign policy is conceived simply as the action of the State, through the government, on the international stage (PINHEIRO; MILANI, 2012, p. 334). The choice of this concept is justified by the necessary emphasis on the politicization of foreign policy, i.e. the perception that the choices made by the government, frequently devoid of systemic coherence, reflect the coalitions, alliances, disputes and bargaining between different sectors of the government itself and of political parties, groups and actors.

Finally, references to solidarity – an enigmatic, complex and ambiguous notion (SUPIOT, 2013a) – carry an elementary definition of public international law, according to which solidarity can mean both instruments of compensation, like the systems of preferential tariffs or redistribution, and instruments for the protection of collective interests, including human rights and sustainable development (BOURICHE, 2012).

The Lula da Silva government quickly realized the role that public health could play in diplomacy. Together with professional training and agriculture, it represents two thirds of Brazilian cooperation with developing countries (VAZ; INOUE, 2007).

Federal investment in health cooperation increased from 2.78 million reais in 2005 to 13.8 million in 2009; as such, 9% of all Brazilian investments in cooperation between 2005 and 2009 were allocated to health (BRASIL, 2010, p. 38). In 2012, of the 107 health cooperation projects in progress, 66 were with Latin America and the Caribbean, 38 with Africa and 9 with the Middle East and Asia; 24 of these projects involved breast milk banks, 17 HIV/AIDS, 10 health surveillance and 10 blood and hemoderivatives (BRASIL, 2012a).

The actors of Brazilian cooperation in health are numerous, each of them contributing their values and their institutional culture, and also their demands. Considered by foreign analysts as “an essential element of Brazil’s solidarity diplomacy” (VENTURA, 2010), health cooperation prompted an unprecedented proximity between the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Foreign Relations (BRASIL, 2012b, p. 26). Foremost among the bodies linked to the Ministry of Health are the Office of International Affairs of the Ministry (Aisa/MS), the National STD and AIDS Program (PN-DST/Aids), the National Cancer Institute (Inca), the National Health Foundation (Funasa), the National Health Surveillance Agency (Anvisa) and the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz) (CEPIK; SOUSA, 2011). In the area of foreign relations, the most prominent is the Brazilian Cooperation Agency (ABC), which oversees the negotiation, coordination and follow- up of the group of technical assistance projects.

This list is by no means exhaustive. It would be impossible, in a single article, to identify and classify all the different forms of international action by Brazilian public bodies that have repercussions on public health. But the complexity of this task is not a monopoly of the health sector: “the fact that nearly 50% of the bodies of the Presidency and the Ministries can engage with foreign policy demonstrates an important internationalization of the structure of the federal executive branch” (SANCHEZ-BADIN; FRANÇA, 2010).

After identifying the origin of the concept of “structural” cooperation in health, the article shall examine the CPLP and UNASUR, given that South-South cooperation occurs, primarily, through agendas established by regional alliances and through strategic plans (BUSS; FERREIRA; HOIRISCH, 2011).

Solidarity constitutes one of the key fundamentals of Brazilian foreign policy (AMORIM, 2010). But it is also the alma mater of the country’s public health system, known as the Unified Health System (SUS), which was created by the Federal Constitution of 1988. The Constitution guarantees universal and free access to health care, which is recognized as a right of all and a duty of the State. Considered the world’s most far-reaching public health system (FORTES; ZOBOLI, 2005, p. 22), with a potential public of almost 200 million citizens, the SUS is based on five fundamental principles: universality, integrality, equality, decentralization and social control. The health councils that operate on federal, state and municipal levels are formed by users, health professionals and administrators, and are responsible for approving health programs, monitoring their performance and controlling their budgets, while also organizing health conferences that are held periodically (FERREIRA NETO; ARAÚJO, 2012). Despite the underfunding of the SUS, the growth of private health insurance, the increasing prominence of private entities within the public system and the serious dysfunctions that are caused by these factors, Brazil can boast progress in its health indicators. The United Nations Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), for example, were reached three years before their deadline (2015) in the field of reducing infant and maternal mortality, as well in combating malaria and other diseases (BRASIL, 2013).

It is the doctrine of the SUS, which advocates universal, equal and integral health coverage, that is the primary inspiration for the concept of “structural cooperation in health” developed by Brazil over the past decade. It is doubly innovative in relation to the paradigm of international cooperation. First, because it is intended to break with the tradition of the passive transfer of knowledge and technology. Second, because its fundamental objective is to create or strengthen the principal fundamental institutions of the health systems in the beneficiary countries, exploring local capacities to the full (ALMEIDA, 2010, p. 25).

While the international cooperation offered by the developed world is, in general, aimed at tackling diseases or specific vulnerabilities, Brazil’s structural cooperation is geared towards supporting the health authorities, developing schools of professional training and confronting the weaknesses of national health systems. In other words, structural elements prevail over cyclical, isolated and temporary aid. This results in the primacy of the permanent national interests of the partners, breaking with the “hegemony of supply” – i.e. the construction of a cooperation agenda based essentially on the interests of the donor, which does not always correspond to the primary needs of the recipient – that characterizes traditional development cooperation (FONSECA et al., 2013).

Paulo Buss, coordinator of the International Relations Center of the influential organization Fiocruz, explains Brazil’s vocation for cooperation with the South: “twenty years ago, we were in the same situation that these countries find themselves in today. We can understand their situation” (PINCOCK, 2011, p.1738).

Created in 1996, the CPLP is currently formed by eight States: Angola, Brazil, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, Portugal, São Tomé and Príncipe, and East Timor. The CPLP supports cooperation in all fields, including health; the promotion and dissemination of the Portuguese language; and diplomatic coordination among its members, with a view to strengthening its presence on the international stage (COMUNIDADE DOS PAÍSES DA LÍNGUA PORTUGUESA, 2007). It is a “phonic space”, institutionalized on the image of the francosphere or the hispanosphere, which until now has evoked no more than a “polished indifference” from multilateral bodies and the international media (FERRA, 2007, p. 98). Nevertheless, cooperation in health with the CPLP was a “natural choice” for Brazil, since the majority of professionals from the Portuguese-Speaking African Countries (PALOP), all of which are members of the CPLP, speak only Portuguese and local languages. The “political, ideological and cultural identities” (BUSS; FERREIRA, 2010a, p. 109) shared by Brazil and the PALOP countries also favor this cooperation.

A full 12 years passed after the creation of the CPLP before the 1st Meeting of Ministers of Health was held, in Praia, Cape Verde. Before then, cooperation in health within the CPLP was focused primarily on combating HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis. Later on, it became part of the CPLP’s Strategic Plan for Cooperation in Health (PECS) for 2009-2012.

Adopted in Estoril, in 2009, at the 2nd Meeting of Ministers of Health, the PECS was allocated a modest budget of 14 million euros. It establishes seven strategic topics: creation and development of a “workforce in health”, which receives 67% of the total PECS budget; information and communication; health research; development of production chains; epidemiological surveillance; natural disasters and emergencies; and health promotion and protection. A technical group is responsible for the coordination and application of PECS.

The priority given to the training of health personnel permits a better understanding of the notion of “structural” cooperation. It is about supporting national health authorities, so they can manage their respective health systems in an efficient, effective and lasting manner; providing training to health professionals; producing or generating useful data for the political decision-making process; and promoting research and development (BUSS; FERREIRA, 2010a, p. 117). The result has been that specific programs to combat diseases have been substituted by investments in the elements of potential structural change in the partner countries.

In the absence of an official report on the results of PECS, it is worth referring to a study that examined 167 bilateral legal acts related to cooperation in health between Brazil and the PALOP countries that were in effect in Brazil in 2009, including memoranda and working plans (TORRONTEGUY, 2010). The author concludes that this cooperation does indeed exclude both the conditionalities and the notion of indebtedness that are characteristic of North-South cooperation. However, the activities established by these instruments are still “one way”, in that the beneficiary State maintains a passive position: of a recipient of aid. The study also reveals that these instruments do not, in general, include accountability mechanisms.

But Brazilian cooperation in health is not limited to the PALOP countries. According to the ABC, projects are currently in progress in Algeria, Benin, Botswana, Burkina-Faso, Republic of Congo, Ghana, Kenya, Senegal and Tanzania. Grouped together, Brazil’s “African policy” has been the target of numerous criticisms. As a new priority of foreign policy, it reflects a concerted strategy between the public sector and the business community to expand Brazilian capitalism, since the government has, via the National Development Bank (BNDES), broadly encouraged the internationalization of Brazilian companies in Africa (SARAIVA, 2012, p. 98 e 129). Although closer relations with Africa is portrayed as solidarity diplomacy, the Brazilian strategy follows an economic logic that is common to so-called emerging powers, namely the search for strategic raw materials and markets for its industrial production (VENTURA, 2010). The international expansion of Brazilian companies has, in some cases, had negative effects on countries and on relations with workers and local governments; some projects financed by the BNDES, which have increased social and environmental vulnerability, have generated conflicts in the recipient countries (GARCIA, 2012, p. 240). As such, publicly-run initiatives in the field of health come across as compensation for the type of South-South cooperation that is based on market interests.

Within the scope of UNASUR, cooperation in health draws on the experience of the Andean Health Organization – Hipolito Unanue Agreement (ORAS-CONHU), in place since 1971; the Common Market of the South – Health (MERCOSUR-Health), focused specifically on health issues related to the circulation of goods and merchandise; and the Health Coordination Office of the Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization (OTCA), which since 1978 has promoted health cooperation in the Amazon region. Unlike these initiatives, however, UNASUR proposes to cover the entire subcontinent.

Created by the Treaty of Brasília, in May 2008, UNASUR remains loyal to Brazil’s long-standing ambition to develop a regional integration that encompasses all of South America and that is not focused only on trade (DABENE, 2010). One of the specific goals of the organization is universal access to social security and health services. The efforts of the member states have turned health into one of the most dynamic fields of regional integration.

The UNASUR treaty, while reflecting Latin America’s progressive orientation of the 2000s, reveals an institutional modesty that betrays the hesitancy of the left on the subject of regional integration (DABENE, 2012, p. 392). Entirely intergovernmental, its organic structure is comprised of three higher councils – of Heads of State, of Foreign Ministers and of National Delegates; an office of the Secretary General, based in Quito, Ecuador; a one year pro tempore presidency; and 12 councils devoted to specific sectors of cooperation.

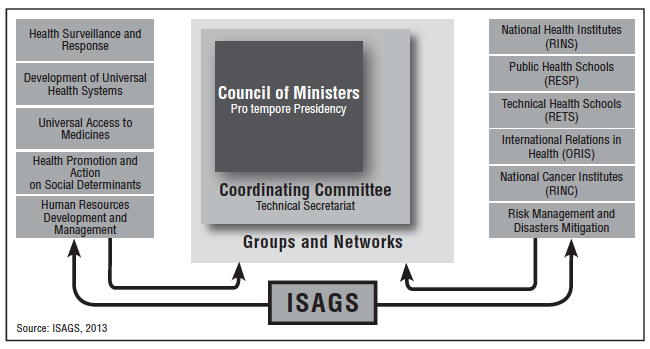

One of these sectoral councils is the South American Health Council, also known as UNASUR-Health, which was established just months after the creation of UNASUR itself, in December 2008. The only sectoral council with its own permanent headquarters is the energy council, which is located in Venezuela. There are also two secondary bodies that are permanent: the Center for Strategic Defense Studies (CEED), based in Buenos Aires; and the South American Institute of Government Health (ISAGS). The structure of UNASUR-Health is illustrated in the figure below.

UNASUR-Health is guided by a Five-Year Plan (2010-2015) (UNASUL, 2010), which contains 28 cooperation goals, organized into five fields that are listed on the left of the figure. From a total budget of 14.4 million U.S. dollars, 10.5 million (nearly 70%) are allocated to the first field, referring to the South American health surveillance policy, which includes, among other things, cooperation between member states for implementing the International Health Regulation (RSI).

In UNASUR-Health, public policies are conceived regionally, in order to develop joint responses to common problems. Paulo Buss and José Roberto Ferreira, in a seminal paper on the topic, refer to medicines, vaccines and diagnostic reagents as “regional public goods” (BUSS; FERREIRA, 2011, p. 2705).

Furthermore, at the heart of UNASUR’s minimalist structure is ISAGS, created by Resolution CSS 05/2009 in November 2009 and installed in Rio de Janeiro on July 25, 2011. Although still young, ISAGS is extremely dynamic and has become a mouthpiece for UNASUR-Health, heading up numerous initiatives. Boasting an institutional innovation not found in other regional integration processes (TEMPORÃO, 2013), ISAGS emerged from a consensus among the Ministers of Health in the region that the most serious problems facing their public health systems are associated with governance (BUSS, 2012). According to article 2 of its Statute, the goal of ISAGS is to become a center of advanced studies and debate on policies for the development of leaders and strategic human resources in health (CONSELHO SUL-AMERICANO DE SAÚDE, 2011), by promoting and offering inputs for health governance in South American countries and its regional articulation in global health. In addition to the formation of a “new generation” of managers, the institute contributes to the adoption of concerted measures on the organization of health services (PADILHA, 2011). UNASUR-Health is also a means of coordinating the positions of the States, both in multilateral fora and with transnational actors.

On the other hand, UNASUR-Health has no mechanisms of social control or participation. This omission is surprising given not only the principles of the SUS, but also the characteristics of UNASUR itself: it is unlikely that another international organization’s constitutive treaty will mention social participation so many times, going so far as to recognize it as a specific goal of the bloc (VENTURA; BARALDI, 2008, p. 15).

Besides UNASUR, Brazil develops health cooperation projects with other Latin American countries. In Haiti, for example, it is leading the reconstruction of the country’s health system, allocating 85 million U.S. dollars for the construction of hospitals, primary health care and training personnel (TEMPORÃO, 2012). Nonetheless, there is a growing conviction that “if proof exists of the failure of international aid, Haiti is it” (SEITENFUS, 2010).

In general, however, this structural South-South cooperation in health is considered positive, despite there being a certain discrepancy between the grandiloquence of the intent and the realization of the gesture (BUSS; FERREIRA, 2010b, p. 102). The health cooperation actors themselves consider it necessary to better coordinate all the agencies and bodies involved. The high-level actors support the adoption of a law in Brazil on international cooperation (BUSS; FERREIRA, 2012, p. 262), in order to better clarify the role of each body of the Brazilian State, guarantee its submission to the principles contained in the Federal Constitution (and, in the case of health, the SUS) and institute accountability mechanisms, which are currently non-existent.

Among the numerous areas of Brazilian action in the field of health, this article addresses the HIV/AIDS program and the policy of access to medicine, the coordination of the BRICS countries in the health sector and the positions of Brazil – and UNASUR – in relation to the process of reforming the WHO. Given the space constraints, the article overlooks some important topics, such as the leading role played by Brazil in the process of drafting the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, among many others.

As the epicenter of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Latin America (BIEHL, 2009, p. 17), Brazil was the first developing country to offer, starting in 1996, free treatment to infected people. As such, universal access to antiretroviral drugs constitutes a key element of the Brazilian position on global health governance, particularly concerning the aspects related to intellectual property. Within the framework of the WHO, Brazil and India were frontrunners among developing countries when the Declaration on the Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) and Public Health, known as the Doha Declaration, was adopted on November 14, 2001.

Nevertheless, there is still a long way to go before public health can take precedence over the economic interests of the pharmaceutical industry. Between 2008 and 2009, for example, European customs authorities seized several shipments of legitimate generic drugs in transit through its ports, in particular a consignment of the generic drug Losartan Potassium, used for hypertension, which was produced in India and en route to Brazil. India and Brazil appealed to the WTO, considering that the conduct of the European authorities violated, among other agreements, the Doha Declaration, by creating obstacles to the legitimate trade of generic drugs (ORGANIZAÇÃO MUNDIAL DO COMÉRCIO, 2009). Brazil has defended the production of generic drugs in other fora, in particular the WHO and the UN General Assembly.

An important study by André de Mello e Souza (2012) on Brazilian foreign policy in light of the AIDS epidemic reveals that Brazil’s policy was formulated in a context of strong opposition from developed States and some large companies and, similarly, in contrast from what was being advocated at the time by the WHO, the United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), the Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO), the World Bank and the Gates Foundation, among others. Souza considers that one possible explanation for the Brazilian position is the convergence between governments (national and local) and civil society organizations, all heavily influenced by the ideas of the aforementioned movement for health reform.

Considered a model response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic, the Brazilian program closely combines the policy of free distribution of medicines and, given the high price of brand-name antiretroviral drugs, the policy of stimulating local pharmaceutical production, whether public or private (CASSIER; CORRÊA, 2009). This model came about as a result of Brazil’s international cooperation. A Horizontal Technical Cooperation Group (HTCH) on HIV/AIDS was created by 21 countries from Latin America and the Caribbean. But it was the creation of the drugs factory in Mozambique that was the catalyst for exporting the Brazilian model. As Africa’s first fully public drug company, this project flourished primarily after 2008, when it started to be managed by Fiocruz – more specifically, by its technology institute in pharmaceutical products, FARMANGUINHOS. Mozambique is one of the countries in the world most ravaged by AIDS, with 1.7 million contaminated people from a population of 21.4 million (OLIVEIRA, 2012). In November 2012, the company presented the first antiretroviral drugs to the Mozambique government (MATOS, 2012).

Since it invested nearly 40 million reais in this project between 2008 and 2014, in addition to the costs of transferring technology for 21 drugs, Brazil was considered more like an activist than a donor, since it received no economic benefit from this cooperation (FOLLER, 2013) – which distinguishes it not only from the developed world, but also from other emerging countries, such as China.

However, the Brazilian model is not immune to criticism. The combination of the activism of patients, the interests of the pharmaceutical industry and the reform policies of the Brazilian State led to a progressive shift in the concept of public health, today viewed less as a mechanism for prevention and medical treatment, and more like a policy of access to drugs and health services; i.e. an increasingly more privatized and pharmaceutical concept of public health that, particularly in the case of the AIDS policy, reproduces prejudices related to color and poverty (BIEHL, 2009, p. 16).

Nevertheless, thanks to its response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic, Brazil has become an “agenda setter” in the health sector (BLISS et al., 2012).

Brazil also frames its action within the group of countries known as the BRICS, which has brought together emerging countries in annual summits of heads of States and Government since 2009. At the Sanya summit, in April 2011, the heads of States and Government decided to strengthen the dialogue in the field of public health, in particular in the fight against HIV/AIDS. Not long afterwards, in July of the same year, the bloc’s health ministers met for the first time, in Beijing, and adopted a declaration that listed all the similar challenges faced by the bloc’s countries, especially those involving access to health services and medicines.

The Beijing Declaration defines the following priorities of action: the strengthening of the health systems, in order to overcome the obstacles of access to vaccines and medicines in the fight against HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, viral hepatitis and malaria; and the transfer of technologies in support of public health (BRICS, 2011).

The question of medicines carries special importance within the BRICS, since China and India are currently the largest suppliers of active ingredients for the Brazilian industry. Accordingly, Brazil intends to “increase effective horizontal cooperation and harmoniously develop capacities between the pharmaceutical sectors of the BRICS countries” and may “also assume a prominent role in the implementation of the Global Strategy on Public Health, Innovation and Intellectual Property, approved by the World Health Assembly in 2008” (PADILHA, 2011a).

The second meeting of the BRICS health ministers occurred in New Delhi, in January 2013, resulting in a communiqué that emphasized, among other things, the need to protect the circulation of generic drugs between developing countries (AGÊNCIA DE NOTÍCIAS DA AIDS, 2013).

Recent studies have drawn attention to the need to intensify research on the real possibilities of the BRICS to have an impact on world health (HARMER et al., 2013).

The past few years have been marked by a growing engagement by Brazil in the WHO. In 2013, at the most recent meeting of the World Health Assembly (WHA), the highest decision-making body of the WHO that convenes annually in Geneva, Brazil became the tenth largest contributor to the institution’s budget: its allocation increased from 1.6% to 2.9% of total State contributions, and will represent nearly 26 million U.S. dollars over the next two years (CHADE, 2013). Moreover, Brazil was elected to the Executive Board of the WHO for the 2013-2016 period.

This engagement has been accompanied by a vigorous criticism of the role of the WHO in global health governance. The Brazilian position on the reform of the organization illustrates this well, since the country has reprehended the Director-General’s Office of the WHO for the haste with which it is conducting the reform process and for giving in to pressure from the major WHO donors that have the most to gain from speeding up the reform, given their well-defined positions (ISAGS/UNASUL, 2013b, p.4).

The Member States of UNASUR have taken steps to coordinate their positions within the WHO over the past two years. UNASUR-Health has met in parallel to the WHA, in order to adopt common positions and speak with a single voice, including in the executive board of the organization (INSTITUTO SUL-AMERICANO DE GOVERNO EM SAÚDE, 2013a).

The critical position of Brazil in relation to the WHO also extends to the debate on the post-2015 Development Agenda, within the framework of the thematic consultation on health. The WHO, together with other actors, defends universal health coverage, while Brazil has proposed a coverage that is not only universal, but also equal and integral. According to Paulo Buss, the Federal Constitution and the concept of health that it guarantees are the only possible parameters of international action by Brazil (ESCOLA NACIONAL DE SAÚDE PÚBLICA, 2013).

One of the risks of the current use of the expression “solidarity”, by States, that threatens to reduce it to an empty slogan is its disconnection from a concrete application framework (BLAIS, 2007, p. 330). By evoking social rights, which encompass the right to health, Alain Supiot recommends moving from a “negative solidarity”, that currently prevails in relations between States, to a “positive solidarity”, that would establish common goals on decent work and justice in the international rules of trade and also create “the means to assess these rules in the light of their real effects on the economic security of men” (SUPIOT, 2010, p. 173).

This article has demonstrated that Brazil clearly does have a foreign policy in the field of health. It is solidary when it defends, for example, that international trade should be subject to human rights on matters of intellectual property, that social determinants have priority on the global agenda and that a reform of the WHO will make it more independent from the major private donors.

However, the other facets of Brazil’s international action also need to be considered, such as the predatory exploration of human labor and natural resources in certain countries by Brazilian companies, many of which benefit from public financing, whose business ventures may have harmful effects on the people’s health in these countries.

Furthermore, unlike the national administration of public health, Brazil’s international action in the field of health is still not equipped with mechanisms of transparency and social participation in its decision-making process, and the same applies to the control of its results.

Mireille Delmas-Marty explains that, given the contradictory effects of globalization, it is not enough simply to reaffirm humanist principles to change practices and promote the necessary rebalance between commercial values and non-commercial values, between private goods and the common good. It is necessary to directly address its very contradictions (DELMAS-MARTY, 2013, p. 96). As such, Brazilian health diplomacy may only be considered effectively solidary when it produces tangible health improvements in the population of the States with which Brazil cooperates. The concept of structural cooperation in health is a valuable Brazilian addition to the international lexicon of development aid. However, the resources allocated to this new type of cooperation are still modest.

The statistics on cooperation, besides not being widely available, need to be analyzed carefully. Indeed, there is an urgent need to encourage qualitative empirical research on the effects of cooperation all over the world. The results of the international cooperation actions need to be studied “more scientifically”: the “protoscience” that is currently used to assess cooperation does not guarantee that the already scarce resources are employed in the best possible manner (KOURILSKY, 2011, p. 17).

The future of Brazilian health diplomacy, which cannot be dissociated from the effects of the country’s overall foreign policy, depends on the internal arbitration of numerous contradictions. On the one hand, between Brazil’s international action and the principles of the SUS; and on the other, between the principles and the reality of the SUS inside Brazil. According to José Gomes Temporão (2013), an arduous political battle is underway to preserve the public and universal health system in Brazil, which is currently under threat of “Americanization” through the dissemination of the idea that private health care is better than public health care, and that the acquisition of health insurance is an important part of Brazilian social mobility (DOMINGUEZ, 2013, p. 19). Moreover, private interests have infiltrated the SUS, whose coherence is being threatened by the increasing number of dubious public-private partnerships (OCKÉ-REIS, 2012).

It can be concluded that the tensions in Brazilian foreign policy, particularly those in the field of public health, are cross-cutting, encompassing the internal and external spheres, and that they multiply as opaquely as they do rapidly. The consolidation of a solidarity diplomacy in health depends both on the prevalence of human rights over other interests of our foreign policy, and on the political will of governments to complete the movement that began with the health reform, developing a free and high-quality health system, as a duty of the State and a right of all, and that underpins Brazil’s international action.

Bibliography and other sources

Agência de notícias da AIDS. 2013. Reunidos na Índia ministros da saúde do BRICS se comprometem a apoiar luta mundial contra AIDS. 11/01/2013. Available at: http://www.agenciaaids.com.br/noticias/interna.php?id=20201. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

ALMEIDA, Célia Almeida et al. 2010. A concepção brasileira de cooperação Sul-Sul estruturante em saúde. RECIIS, v.4, n.1, p. 25-35, março. Available at: http://www.reciis.icict.fiocruz.br/index.php/reciis/article/viewArticle/343. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

AMORIM, Celso. 2010. Em entrevista. Cooperação Saúde, Boletim da Atuação Internacional Brasileira em Saúde, Brasília, n. 2, p. 4-5. Available at: http://portal.saude.gov.br/portal/arquivos/pdf/boletim_aisa_final.pdf. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

BIEHL, João. 2009. Accès au traitement du Sida, marchés des médicaments et citoyenneté dans le Brésil d’aujourd’hui. Sciences sociales et santé, v. 27, n. 3, p. 13-46. Available at: http://www.cairn.info/revue-sciences-sociales-et-sante-2009-3-page-13.htm. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

BIRN, Anne-Emanuelle. 2011. Reconceptualización de la salud internacional: perspectivas alentadoras desde América Latina. Revista Panamericana de Salud Publica, v. 30, n. 2, p. 101-104.

BLAIS, Marie-Claude. 2007. La solidarité – histoire d’une idée. Paris: Gallimard.

BLISS, Katherine; BUSS, Paulo; ROSENBERG, Felix. 2012. New Approaches to Global Health Cooperation–perspectives from Brazil. Brasil: Ministério da Saúde/Fiocruz; Washington, D.C: Center for Strategic and International Studies, set. Available at: http://csis.org/files/publication/120927_Bliss_NewApproachesBrazil_Web.pdf. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

BOURICHE, Marie. 2012. Les instruments de solidarité en droit international public. Paris: Connaissances et savoirs.

BRANDT, Allan. 2013. How AIDS Invented Global Health. The New England Journal of Medicine, n. 368, p. 2149-2152, 06 jun. Available at: http://www3.med.unipmn.it/papers/2013/NEJM/2013-06-06_nejm/nejmp1305297.pdf. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

BRASIL. 2010. SAE/PR-IPEA-MRE-ABC. Cooperação brasileira para o desenvolvimento internacional: 2005-2009. Brasília, Dezembro. Available at: http://www.ipea.gov.br/portal/images/stories/PDFs/Book_Cooperao_Brasileira.pdf. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

_______. 2012a. Ministério da Saúde. Participação do Ministério da Saúde no cenário internacional da saúde. Ciclo de Debates. Brasília, Ministério da Saúde. Available at: http://portal.saude.gov.br/portal/arquivos/pdf/ms_cenario_internacional_saude.pdf. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

_______. 2012b. SISCOOP-DPROJ/AISA. A Cooperação Brasileira em Saúde, Apresentação. Brasília, 19 de dez.

_______. 2013a. Agência Brasileira de Cooperação. Site oficial. Available at: www.abc.gov.br. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

_______. 2013b. Senado Federal. Agência Senado. Ao apresentar balanço do Ministério da Saúde, Padilha reconhece que falta de médicos é “desafio crítico”. Portal de Notícias, Brasília, 24/04/2013. Available at: http://www12.senado.gov.br/noticias/materias/2013/04/24/ao-apresentar-balanco-do-ministerio-da-saude-padilha-reconhece-que-falta-de-medicos-e-desafio-critico. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

BRICS. I Reunião dos Ministros da Saúde dos BRICS. Declaração de Pequim. Tradução de Vera Golik e Hugo Lenzi. Available at: www.amucc.com.br. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

BUSS, Paulo; CHAMAS, Claudia. 2012. Um novo modelo para a pesquisa em saúde global. Valor Econômico, 31 ago.

BUSS, Paulo; FERREIRA, José Roberto. 2010a. Diplomacia da saúde e cooperação Sul-Sul: as experiências da UNASUL saúde e do Plano Estratégico de Cooperação em Saúde da CPLP. RECIIS, v. 4, n. 1, março, p. 106-118. Available at: http://www.reciis.icict.fiocruz.br/index.php/reciis/article/view/351. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

________. 2010b. Ensaio crítico sobre a cooperação internacional em saúde. RECIIS, v. 4, n. 1, março, p. 93-105. Available at: http://www.reciis.icict.fiocruz.br/index.php/reciis/article/viewArticle/350. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

________. 2011. Cooperação e integração regional em saúde na América do Sul: a contribuição da UNASUL Saúde. Ciência e Saúde Coletiva, v. 16, p. 2699-2711. Available at: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/csc/v16n6/09.pdf. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

________. 2012. Brasil e saúde global. In: Política externa brasileira – As práticas da política e a política das práticas. Rio de Janeiro: FGV.

BUSS, Paulo; FERREIRA, José Roberto; HOIRISCH, Claudia. 2011. A saúde pública no Brasil e a cooperação internacional. Revista Brasileira de Ciência, Tecnologia e Sociedade, v. 2, n. 2, p. 213-229. Available at: http://www.revistabrasileiradects.ufscar.br/index.php/cts/article/viewFile/160/88. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

CABRERA, Oscar; GUILLÉN, Paula; CARBALLO, Juan. 2013. Restrições à publicidade e promoção do tabaco e a liberdade de expressão. Conflito de direitos? Revista de Direito Sanitário, v. 13, n. 3, p. 98-123. Available at: http://www.revistas.usp.br/rdisan/article/view/56245. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

CASSIER, Maurice; CORRÊA, Marilena. 2009. Éloge de la copie: le reverse engineering des antirétroviraux contre le VIH/Sida dans les laboratoires pharmaceutiques brésiliens. Sciences sociales et santé, v. 27, n. 3, p. 77-103. Available at: http://www.cairn.info/revue-sciences-sociales-et-sante-2009-3-page-77.htm. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

CEPIK, Marco; SOUSA, Romulo Paes. 2011. A política externa brasileira e a cooperação internacional em saúde no começo do governo Lula. Século XXI, v. 2, n. 1, p. 109-134, jan.-jul. Available at: http://sumario-periodicos.espm.br/index.php/seculo21/article/viewFile/1779/90. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

CHADE, Jamil. 2013. Brasil vai dobrar contribuição para a OMS em 2014. Estadão [online], 23/05/2013. Available at: http://www.estadao.com.br/noticias/vidae,brasil-vai-dobrar-contribuicao-para-a-oms-em-2014,1034996,0.htm. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

COMUNIDADE DOS PAÍSES DA LÍNGUA PORTUGUESA (CPLP). 2007. Estatuto. I Cúpula de Chefes de Estado e de Governo, Lisboa, 1996 – atualizado em São Tomé (2001), Brasília (2002), Luanda (2005), Bissau (2006) e Lisboa (2007).

________. 2009. Plano Estratégico de Cooperação em Saúde 2009-2012. II Reunião de Ministros de Saúde, Estoril.

________. 2013. II Reunião Ordinária da Rede dos Institutos Nacionais de Saúde Pública da CPLP (RINSP/CPLP). Ata da Reunião. 19 de abril.

DABENE, Olivier. 2010a. L’UNASUR–Le nouveau visage pragmatique du régionalisme sud-américain. Political Outlook 2010, Observatoire politique de l’Amérique latine et des Caraïbes (Opalc), CERI-Sciences Po. Available at: http://www.sciencespo.fr/ceri/sites/sciencespo.fr.ceri/files/etude169_170.pdf. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

_______. 2010b. Au-delà du régionalisme ouvert–La gauche latino-américaine face au piège de la souveraineté et de la flexibilité. In: La gauche en Amérique latine 1998-2012. Paris: Presses de Sciences Po. Chapitre 11.

DABENE, Olivier; LOUAULT, Frédéric. 2013. Atlas du Brésil – Promesses et défis d’une puissance émergente. Paris: Autrement.

Delmas-Marty, Mireille. 2013. Résister, responsabiliser, anticiper. Paris: Seuil.

DOMINGUEZ, Bruno. 2013. Universalidade: o necessário resgate de um sentido perdido. RADIS, n. 127, p.16-19, abril. Available at: http://www6.ensp.fiocruz.br/radis/revista-radis/127/reportagens/universalidade-o-necessario-resgate-de-um-sentido-perdido. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

ESCOLA NACIONAL DE SAÚDE PÚBLICA (ENSP). 2013. Princípios do SUS podem nortear agenda pós-2015. Informe ENSP. 04/04/2013. Available at: http://www.ensp.fiocruz.br/portal-ensp/informe/site/materia/detalhe/32323. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

ESCOREL, Maria Luisa. 2012. Reforma da OMS: Saúde Global e Diplomacia. Apresentação. Taller de Salud Global y Diplomacia de la Salud, ISAGS, Rio de Janeiro, maio.

FERRA, Francisco. 2007. Un espace phonique lusophone à plusieurs voix? Enjeux et jeux de pouvoir au sein de la CPLP. Revue internationale de politique comparée, v. 14, p. 95-129.

Ferreira Neto, Joao Leite; ARAÚJO, Jose Newton. 2012. L’expérience brésilienne du Système unique de santé (SUS): gestion et subjectivité dans un contexte néoliberal. Nouvelle revue de psychosociologie, n. 13, p. 227-239.

FOLLER, Maj-Lis. Cooperação Sul-Sul: a Parceria Brasileira com Moçambique e a Construção de uma Fábrica de Medicamentos de Combate à AIDS. Austral, Revista Brasileira de Estratégia e Relações Internacionais, v. 2, n. 3, p.181-207, jun. Available at: http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:rs5_Ii09oSoJ:seer.ufrgs.br/austral/article/download/35027/23941+&cd=1&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=br. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

FONSECA, Luiz Eduardo et al. 2013. Meio século de cooperação para o desenvolvimento e sua influência no setor saúde. Anais do IV Encontro da ABRI, Belo Horizonte, julho.

FORTES, Paulo; ZOBOLI, Elma. 2005. Os princípios do Sistema Único de Saúde – SUS potencializando a inclusão social na atenção à saúde. O Mundo da Saúde, v. 29, n. 1, p. 20-25, março.

Garcia, Ana Saggioro. 2012. A internacionalização de empresas brasileiras durante o governo Lula: uma análise crítica da relação entre capital e Estado no Brasil contemporâneo. 2012. 413f. Tese (Doutorado em Relações Internacionais)–Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro, Instituto de Relações Internacionais. Available at: http://www.fisyp.org.ar/media/uploads/0812659_2012_completa.pdf. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

Gostin, Lawrence. 2007. Meeting the Survival Needs of the World’s Least Healthy People–A Proposed Model for Global Health Governance. JAMA, v. 298, n. 2, jul., p. 225-8.

HARMER, Andrew et al. 2013. ‘BRICS without straw’? A systematic literature review of newly emerging economies influence in global health. Globalization and Health, 9:15. Available at: http://www.globalizationandhealth.com/content/9/1/15. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

CONSEJO SURAMERICANO DE SALUD. 2011. Resolución N° 02. Estatuto del Instituto Suramericano de Gobierno en Salud. Available at: http://www.isags-unasul.org/media/file/ESTATUTO%20ISAGS%20ESP.pdf. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

INSTITUTO SUL-AMERICANO DE GOVERNO EM SAÚDE. União das Nações Sul-Americanas (ISAGS/UNASUL). 2013a. Informe, Rio de Janeiro, maio.

________. 2013b. Informe, Rio de Janeiro, junho.

KEROUEDAN, Dominique. 2011. Présentation. In: KEROUEDAN (dir.). Santé internationale – Les enjeux de santé au Sud. Paris: Presses de Sciences Po.

________. 2013a. Géopolitique de la santé mondiale. Leçons inaugurales du Collège de France. Paris: Collège de France/Fayard.

________. 2013b. Problématique du Colloque international Politique étrangère et diplomatie de la santé mondiale. Chaire Savoirs contre pauvreté – Géopolitique de la santé mondiale, Collège de France, Paris, junho.

KICKBUSCH, Ilona; BERGER, Chantal. 2010. Diplomacia da Saúde Global. RECIIS, Rio de Janeiro, v. 4, n. 1, p. 19-24, março. Available at: http://www.reciis.icict.fiocruz.br/index.php/reciis/article/view/342. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

KOURILSKY, Philippe. 2011. Les sciences qui s’ignorent. In: KEROUEDAN (dir.). Santé internationale – Les enjeux de santé au Sud. Paris: Presses de Sciences Po. p. 15-18.

LEITE, Iara Costa; SUYAMA, Bianca; WAISBICH, Laura Trajber. 2013. Para além do tecnicismo: a Cooperação Brasileira para o Desenvolvimento Internacional e caminhos para sua efetividade e democratização. Policy Briefing. São Paulo: CEBRAP. Available at: http://www.cebrap.org.br/v2/files/upload/biblioteca_virtual/item_796/26_08_13_14Policy_Briefing_Para%20al%C3%A9m%20do%20tecnicismo.pdf. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

LIMA, Maria Regina S. de. 2005. A política externa brasileira e os desafios da cooperação Sul-Sul. Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional, v. 48, n. 1, p. 24-59, jan./june. Available at: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?pid=S0034-73292005000100002&script=sci_arttext. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

MATOS, Alexandre. 2012. Fábrica de medicamentos de Moçambique entrega primeira remessa. Agência Fiocruz de notícias, 23/11/2012. Available at: http://www.fiocruz.br/ccs/cgi/cgilua.exe/sys/start.htm?infoid=4985&sid=9&tpl=printerview. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

MORIN, Edgar. 2013. L’aventure d’une pensée. Entrevista. Sciences Humaines, hors-série spécial, n. 18, mai-juin.

Ocké-Reis, Carlos. 2012. SUS – o desafio de ser único. Rio de Janeiro: FIOCRUZ.

OLIVEIRA, Lícia. 2012. Coordenadora do projeto da fábrica de medicamentos em Moçambique comenta a iniciativa. Entrevista concedida à Danielle Monteiro. Agência Fiocruz de notícias, 25/05/2012. Available at: http://www.fiocruz.br/ccs/cgi/cgilua.exe/sys/start.htm?infoid=4666&sid=3&tpl=printerview. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

ORGANIZAÇÃO DO TRATADO DE COOPERAÇÃO AMAZÔNICA (OTCA). 2013. Plano de Trabalho 2013. II Reunião Regional Virtual de Saúde. 4 de fevereiro.

ORGANIZAÇÃO MUNDIAL DO COMÉRCIO (OMC). 2009. Sistema de Solução de Controvérsias. Processos DS408 e DS409. Available at: http://www.wto.org/. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

________. 1946. Constituição da Organização Mundial da Saúde. Nova Iorque, 22 de Julho.

PADILHA, Alexandre. 2011a. Intervenção do Ministro de Estado da Saúde do Brasil na I Reunião de Ministros da Saúde do BRICS. Pequim, 11 Jul.

________. 2011b. Padilha comenta a atuação do ISAGS e destaca ações do MS. Informe ENSP. 5 ago.

PATRIOTA, Antonio. 2011. Entrevista. Cooperação Saúde, Boletim da atuação internacional brasileira em saúde, n. 5.

PEREZ, Fernanda Aguilar. 2012. Panorama da cooperação internacional em saúde em países da América do Sul. 2012. 174p. Dissertação (Mestrado em Ciências) – Faculdade de Saúde Pública, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. Available at: http://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/6/6135/tde-06092012-114245/pt-br.php. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

PINCOCK, Stephen. 2011. Pro?le Paulo Buss – A leader of public health and health policy in Brazil. The Lancet, v. 377, p. 1738, May.

PINHEIRO, Leticia; MILANI, Carlos. 2012. Conclusão. In: ________. (Org). Política externa brasileira – As práticas da política e a política das práticas. Rio de Janeiro: FGV, 2012. p. 334-6.

POCHMANN, Marcio. 2012. Nova classe média? O trabalho na base da pirâmide social brasileira. São Paulo: Boitempo.

QUEIROZ, Luisa; GIOVANELLA, Ligia. 2011. Agenda regional da saúde no Mercosul: arquitetura e temas. Rev. Panam Salud Publica, v. 30, n. 2, p. 182-8. Available at: http://www.scielosp.org/pdf/rpsp/v30n2/v30n2a11.pdf. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

SANCHEZ-BADIN, Michelle Ratton; FRANÇA, Cassio. 2010. A inserção internacional do poder executivo federal brasileiro. Análises e Propostas FES, n. 40, agosto. Available at: http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/brasilien/07917.pdf. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

SARAIVA, José Flávio Sombra. 2012. África parceira do Brasil atlântico – Relações internacionais do Brasil e da África no início do século XXI. Belo Horizonte: Fino Traço.

SEITENFUS, Ricardo. 2006. Elementos para uma diplomacia solidária: a crise haitiana e os desafios da ordem internacional contemporânea. Carta Internacional, v. 1, p. 5-12, março. Available at: http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:fRxema72Vy8J:citrus.uspnet.usp.br/nupri/arquivo.php%3Fid%3D9+&cd=3&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=br. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

________. 2010. Haïti est la preuve de l’échec de l’aide internationale–Interview accordé à Arnaud Robert. Le Temps, Genebra, 20 dez.

SUPIOT, Alain. 2010. L’esprit de Philadelphie – la justice sociale face au marché total. Paris: Seuil.

_______. 2013a. Abertura. Entretien sur les avatars de la solidarité. Vídeo. Colóquio da Cátedra “État social et mondialisation: analyse juridique des solidarités”, Paris, Collège de France, 5-6 de junho.

TEMPORÃO, José Gomes. 2012. José Gomes Temporão fala sobre a necessidade de semelhorar a saúde na América do Sul. Entrevista concedida a Ana Cappelano. ISAGS Notícias. 17 abril.

_______. 2013b. Entrevista. ISAGS–Galeria de vídeos, publicado em 25 jul. Available at: www.isags-unasursalud.org/. Last accessed on: July 25, 2013.

TORRONTEGUY, Marco Aurelio. 2010. O papel da cooperação internacional para a efetivação de direitos humanos: o Brasil, os Países Africanos de Língua Oficial Portuguesa e o direito à saúde. RECIIS, v. 4, n. 1, p. 58-67, março. Available at: http://www.reciis.icict.fiocruz.br/index.php/reciis/article/viewArticle/346. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

UNIÓN DE NACIONES SURAMERICANAS (UNASUR). Consejo de Salud Suramericano. 2010. Plan Quinquenal 2010-2015. Available at: http://www.isags-unasul.org/media/file/PLAN%20QUINQUENAL%20abril%202010%20ESP.pdf. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

VAZ, Alcides; INOUE, Cristina. 2007. Les économies émergentes et l’aide au développement international: Le cas du Brésil. Paris: IDRC/CRDI.

VENTURA, Deisy. 2013. Direito e saúde global – o caso da pandemia de gripe A(H1N1). Coleção Direitos e Lutas Sociais. São Paulo: Dobra Editorial/Outras Expressões.

VENTURA, Deisy; BARALDI, Camila. 2008. A UNASUL e a nova gramática da integração sul-americana. In: Pontes entre o comércio e o desenvolvimento sustentável. v. 4, n.3, Porto Alegre, p. 14-16.

VENTURA, Enrique. 2010. La diplomatie Sud-Sud du Brésil de Lula: entre discours et réalité, OPALC/GRIB, Paris, junho. Available at: http://www.sciencespo.fr/opalc/sites/sciencespo.fr.opalc/files/VenturaDiplomatieSud.pdf. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

VISENTINI, Paulo. 2010. Cooperação Sul-Sul, Diplomacia de Prestígio ou Imperialismo “soft”? As Relações Brasil-África do Governo Lula. Século XXI, v. 1, n. 1. Available at: http://sumario-periodicos.espm.br/index.php/seculo21/article/view/1706. Last accessed on: June 14, 2013.

ZYLBERMAN, Patrick. 2013. Tempêtes microbiennes – Essai sur la politique de sécurité sanitaire dans le monde transatlantique. Paris: Gallimard.