Insights based on the work of an organization from the Global South

Based on the foreign policy work done by international organization based in Brazil Conectas Human Rights, this article examines the multilateral and bilateral roles of emerging countries in relation to their postures on international human rights protection. The inconsistencies and challenges revealed provide a starting point for reflecting on Conectas´ approach and for suggesting a series of strategies that may be useful to other civil society organizations seeking to address foreign policy issues.

So-called emerging powers such as South Africa, Brazil, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Nigeria and Turkey have gained international prominence on account of their growing economies, and they play an increasingly active role in defining the direction of international politics. Their alliances, partnerships and fora continue to gain significance and visibility1 and the decisions made by these countries have an impact that reaches far beyond their own borders.

While many emerging countries have focused on reforming global governance and put pressure on multilateral agencies and mechanisms to reflect their new international role, their commitment to improving the international human rights system is less clear. Their performance and conduct in the field of human rights is often inconsistent with their foreign policy activities. For example they frequently abstain in multilateral fora from supporting resolutions condemning flagrant human rights abuses. The governments of some of these countries also have allowed public funds to finance commercial and other developments in foreign countries that contributed to flagrant human rights violations of local people.

It is vitally important, therefore, for civil society in each of these emerging powers to demand transparency and accountability from their governments, as well as consistency between their governments´ human rights commitments and the decisions and positions they adopt on the international stage. One way to do this is to analyze the voting record of a particular country in the traditional international fora, as well as its foreign policy activities at bilateral, regional and multilateral levels, with a view to publicizing information revealing possible or imminent inconsistencies. By working alongside national institutions and other civil society groups, NGOs can contribute to strengthening democracy at the national level. This kind of approach is timely, and can benefit from the fact that the emerging powers have only recently begun to assume a higher profile in multilateral and other fora. This means that civil society in emerging countries at present may be in a better position to bring about effective changes in governments´ foreign policy, than civil society in long-established powers with more “institutionalized” foreign policies.

This paper intends to share the work strategies of Conectas Human Rights2 on the subjects of foreign policy and human rights with other civil society organizations keen to influence the practices of their own governments and possibly even to invite scholars in their respective countries to research the issues for themselves. Some of the discussions and strategies presented in this paper echo those of a recent Conectas publication entitled Foreign Policy and Human Rights: Strategies for Civil Society Action – A view through the experience of Conectas in Brazil (CONECTAS DIREITOS HUMANOS, 2013) which includes, in addition to strategies and suggestions, an account of the organization´s experience over the years of working on foreign policy advocacy.

Conectas began working in the foreign policy area in 2005, at a time when this subject was of limited interest to other Brazilian organizations. Brazil´s foreign policy agenda was primarily defined by executive branch officials, in particular by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (known as Itamaraty3) and was subject to very little scrutiny from Brazilian civil society. Information was not readily forthcoming on many key issues: e.g. How was the government´s foreign policy agenda formulated? What were the decision-making processes of Itamaraty and other government entities driving Brazil´s position on subjects of international importance, such as voting in the UN Human Rights Council and other multilateral fora? How were ambassadors appointed? This dearth of information was also reflected in the Brazilian media, where the subject received scant attention.

Against this background, Conectas created its Foreign Policy and Human Rights Program based on the premise that in a democracy government has the obligation to be accountable to citizens for all its activities and to establish and foster channels for social participation. Given that foreign policy is public policy, civil society has a right to insist on transparency in the formulation and implementation of policies in this field. Furthermore the 1988 Brazilian Federal Constitution states in article 4, Paragraph II, that the country´s international relations must be governed by “the prevalence of human rights” (BRASIL, 1988). It follows that calling for respect for human rights in all of Brazil´s foreign policy decisions is more than simply a matter of principle, but also one of compliance with the constitutional commitment assumed in 1988.4

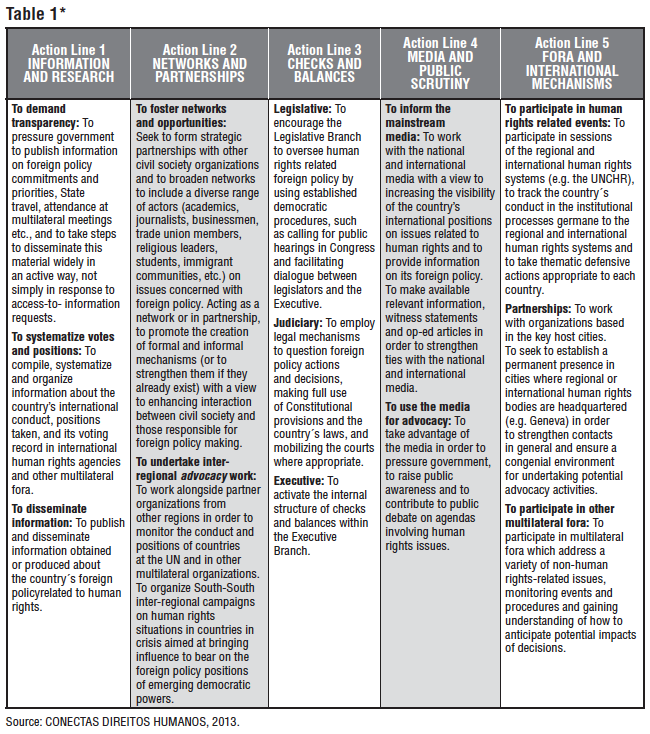

The Table below presents Conectas´ principal action strategies related to its work on foreign policy.

* This publication by Conectas Human Rights presents examples of Conectas actions, the main challenges faced by NGOs and suggestions for action.

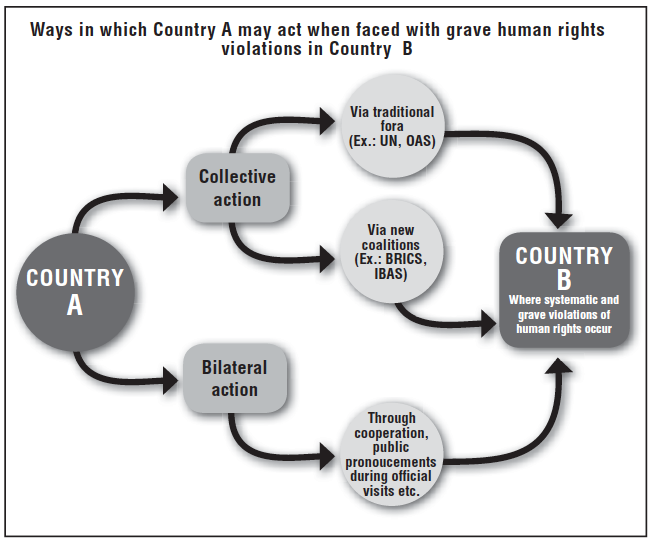

For the purposes of this article, we depart from the principle that States can contribute to the international protection of human rights through bilateral or collective fora. By collective fora, we mean those in which States act on the basis of not only their own national interests and imperatives, but especially in concert with other States. They include traditional multilateral organizations with a high degree of institutionalization, which count on an extensive normative framework regarding human rights, but also other political coalitions not necessarily created exclusively for the protection of such rights – such as the new BRICS and IBAS -, which have been classified as “minilateral” arrangements by some (FONSECA, 2012).

Among the collective fora, an example of a multilateral body is the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC), a subsidiary body of the General Assembly and the world´s leading international human rights body. Its purpose is to seek to contribute to the advancement of international standards that strengthen the promotion and protection of human rights around the globe by inter alia adopting resolutions on thematic issues. The UNHRC also monitors respect for human rights through mechanisms such as: its resolutions on countries where serious or persistent violations of human rights take place; a system of “special procedures” (independent reporting and working groups); and the Universal Periodic Review (UPR), a mechanism under which all UN Member States are subjected every four years to a critical appraisal of their human rights conduct in a formal session where they also receive recommendations from other States participating in the Review. Other multilateral institutions considered part of the official system of human rights protection include those within the mandate of regional organizations such as the Organization of American States (OAS) with its Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and the Inter-American Court on Human Rights. When the multilateral and regional agencies demand more commitment to respect human rights by the emerging nations, the expectation is that these countries will help to bolster international human rights protection mechanisms by maintaining a responsible posture in international and regional fora. This involves their contributing to enhance the rules, strengthening the monitoring capacity of the human rights institutions and complying with their recommendations and rulings.

Increasingly, however, the discussions and decisions that impact on fundamental rights go beyond the remit of the bodies created exclusively for addressing the issue and that are understood to form part of the traditional international human rights system. A multitude of bodies also exists whose primary mandate does not concern human rights, but which nevertheless deal with issues that have a direct impact on the international protection of these rights. Among these are groupings such as IBSA (India, Brazil and South Africa) and BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa). Despite fluctuating between optimism and skepticism about the ability of these groups to challenge the international status quo, there is no denying that they have gained prominence in global debates, including those on human rights. The proliferation of bodies in which human rights are inserted transversely poses a tough challenge to civil society organizations monitoring the conduct of their governments.

Bilateral activities also have an international impact. Decisions on closer political relations with other governments, development aid investments and trade promotion obviously have a major influence on human rights protection in partner countries. Opportunities thus exist in the ambit of bilateral relations between States to promote and protect human rights on a broader, even worldwide scale.

In addition to the traditional diplomatic links nurtured by senior officials from both countries (in a bilateral relationship) and the activities of their embassies around the globe, other aspects of bilateral relations such as the provision of humanitarian assistance and international cooperation call for close inspection since they can have a substantial impact on human and other rights of local populations. Other mechanisms with the same consequences include the controversial system of bilateral sanctions and the practice, increasingly adopted by emerging countries, of providing public financing for commercial promotion of national companies in foreign States.

Conectas, through its Foreign Policy and Human Rights Program, tracks the performance of Brazil and other emerging countries both in terms of their bilateral activities and in regard to their stances in collective fora such as the UN and new coalitions to ascertain whether the positions adopted by these countries are consistent with their principles and commitments on human rights. Some examples are presented below.

The following are samples of foreign policy conducts by some emerging countries which call for closer study since they manifest marked inconsistencies with the rules of international human rights protection. While this behaviour cannot be generalized to all the emerging States, we seek to point out certain weaknesses in the foreign policies of some of the countries monitored by Conectas. The examples aim to illustrate ways in which a Global South human rights organization can do valuable work in the foreign policy field.

At the multilateral level, one of the emerging countries´ main complaints concerns the alleged selectivity of the UN Human Rights Council. This body has been criticized for its lack of consistent and transparent criteria when deciding which countries should be the target of resolutions and which topics should be prioritized. This was clear from the intervention in 2012 of the South African Deputy Foreign Minister, Ebrahim Ismail Ebrahim, who argued that:

…the Council should remain a credible arbiter and deal with all global human rights concerns in a balanced manner. There should be no hierarchy. Economic, social and cultural rights should be on an equal footing and be treated with the same emphasis as civil and political rights.

(SOUTH AFRICA, 2013).

Similarly, the Council has been criticized for neglecting or absolving countries with urgent or chronic human rights crises while simultaneously and repeatedly issuing resolutions on a few states with dubious human rights records such as North Korea. This issue is very much in Brazil´s interest. In 2012, Brazil´s Human Rights Minister Maria do Rosario Nunes affirmed that the UNHRC “must assume position on serious human rights violations wherever they occur, respecting the principles of non-selectivity and non-politicization” (BRASIL 2012a) In the following year the then Brazilian Foreign Minister, Antonio Patriota, argued that the Council should act to improve “the lives of human beings, through a balanced and non-selective approach to human rights, free from futile objections and paralyzing polarization” (BRASIL, 2013).

However, criticism of the selectivity of the UNHRC is not always accompanied by consistent behaviour by the emerging States. A striking example was the case of Bahrain which, despite the serious violations committed there and the condemnation by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Navi Pillay,5 received little attention from the Council.

The human rights situation in Bahrain deteriorated from February 2011, when peaceful protests for democratic reforms commenced. Despite the serious human rights situation, the UNHRC kept silent for over a year. Seeking to reverse this situation, 26 human rights organizations in June 2012 demanded all delegations in Geneva to desist from turning a blind eye to the events in Bahrein (JOINT…, 2012). During the 20th UNHRC session, 27 States6 finally issued a Joint Statement showing concern about the situation in Bahrain. Among the emerging countries that had criticized the Council for its selectivity, such as South Africa, Brazil, India, Indonesia, Nigeria and Turkey, only Mexico signed this statement. The violations continued apace in Bahrein, leading in February 2013 to a further joint appeal for the abuses to be investigated by the Council (JOINT…, 2013a). At the 22nd UNHRC session 44 countries7 appended their names to a second Joint Statement. Once again Brazil, South Africa, Nigeria, India, Indonesia and Turkey failed to sign. And once again Mexico was an exception.8 The subject was revisited at the 24th session, in September 2013, after robust civil society action demanding the adoption of a resolution on Bahrain and pressuring countries that had not adhered to previous statements to join in this fresh initiative. While the result was yet another statement (the idea of a specific resolution was dropped) one positive point emerged: Brazil, which previously had merely chosen to make its own statement on the Bahrein situation, finally joined Mexico as one other emerging nation to sign the new statement (JOINT…, 2013b). Conectas played a role in all the collective initiatives reported here.

As a way of pointing to the contradictions between talk and action, Conectas has since 2006 published the yearbook Human Rights: Brazil at the UN. This publication contains information about Brazil´s votes at the UN and recommendations made and received by Brazil on human rights. In addition to providing data for researchers and/or other organizations involved with human rights, the Yearbook is an ideal vehicle for making clear to the Brazilian government that its conduct in multilateral forums is closely followed by civil society.

Before 2009 monitoring of UN votes was done either virtually or by Conectas representatives attending sessions in Geneva on an ad hoc basis. In 2010, the organization joined forces with two other Latin American organizations – the Center for Legal and Social Studies (CELS) based in Argentina and Corporación Humanas from Chile – to appoint a permanent representative in Geneva. As well as tracking voting at the UN, this partnership of three organizations made it possible to undertake joint actions on different fronts in Geneva.

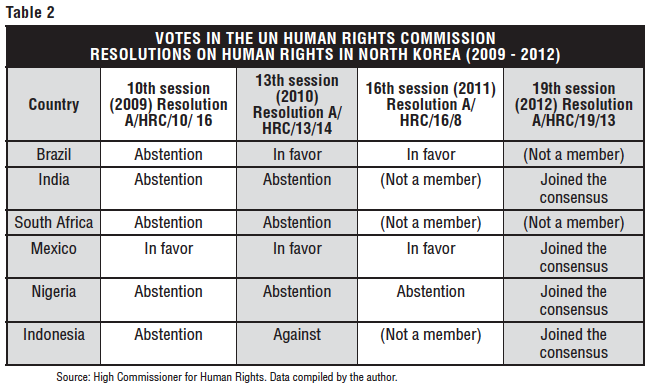

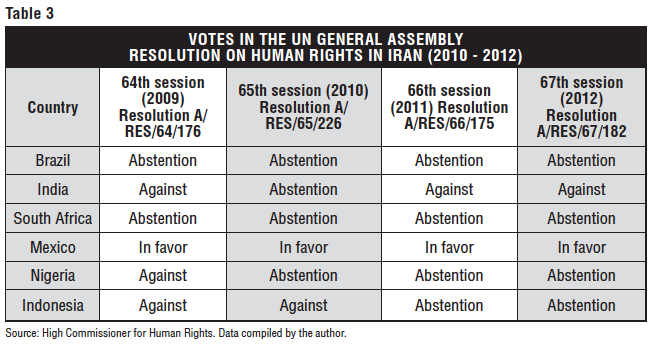

As regards voting patterns, Conectas observed fluctuations from year to year in the support given by emerging countries such as Brazil, Mexico,9 Nigeria, South Africa, India and Indonesia to UN resolutions targeted at violations in specific countries. While the human rights component of a particular country´s foreign policy is not necessarily reflected only in the way it votes on resolutions in the UNCHR and the UN General Assembly, it nevertheless provides important pointers to its general direction on the subject. The UNCHR and the UNGA provide, afterall, a benchmark for setting minimum limits to the international acceptance of human rights violations. Monitoring votes thus allows civil society to detect inconsistencies and to concentrate advocacy efforts on causes or countries that receive less attention in multilateral fora.

The following are examples of the above-mentioned fluctuations and Conectas´ strategies for influencing Brazil´s votes at the UN:

North Korea

Human rights violations in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) have been the subject of international concern for many years. Since 2003 the former UN Human Rights Commission10 and the current HRC adopted a number of resolutions expressing misgivings about the human rights situation in that country.

While Brazil had previously voted in favor of several procedures on North Korea, it abstained in the UNGA in 2008 and again the following year, both at UNGA and the HRC. As the above chart shows, India and South Africa abstained, Indonesia and Nigeria voted against and, once again, Mexico voted in favor.

Arguing that Brazil´s abstention violated the country´s constitutional principle of respect for human rights in the conduct of foreign policy (Federal Constitution, article 4, II), Conectas approached the Federal Public Prosecutors Office in Brasilia to ask it to demand an explanation of Brazil´s vote from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Itamaraty responded that it had abstained in the belief that the way forward was to create a political and diplomatic environment capable of allowing North Korea to voluntarily commit to human rights and cooperate with the UN. In the event, North Korea refused to accept all the recommendations made by the 2009 UPR mechanism, including those put forward by Brazil. As a result Brazil changed its position in 2010, joining Mexico to vote in favor of the resolution. From 2012 onwards, resolutions on North Korea were adopted by consensus and a Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in the Democratic People´s Republic of North Korea was later adopted (in March 2013), also by consensus of all members of the UNCHR. In short, it is clear that the request for information made by another government body (in this case the FPPO) was useful for eliciting the required information (i.e. an explanation of Brazil’s position), and at the same time forced Itamaraty to confront the failure of its adopted strategy, and to remedy this by assuming a more robust attitude for human rights.

Iran

In the voting on the human rights situation in Iran at UNGA, India, Brazil, South Africa, Nigeria, Indonesia were notable for their questionable voting conduct. An analysis of the votes from 2009 onwards shows that among the so-called emerging countries group, only Mexico voted in favor of the resolutions on Iran. Brazil had in fact abstained since 2001 (except in 2003) on all the resolutions condemning human rights violations in Iran. This was also the case of South Africa, Nigeria and Indonesia (the latter two had voted against in previous years). India also wavered between abstention and voting against the resolution with final prevalence of the latter.

To raise the Brazilian government´s awareness on the issue, Conectas organized a series of meetings between Iranian activists and Brazilian government and civil society representatives aimed at persuading Brazil to take a stronger position. The outcome was that within a month (on 24 March 2011) Brazil voted in favor of the UNHRC adopting a resolution “establishing the mandate of a Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran”. Since then Conectas has kept a close watch on Brazil’s position on Iran, and continues to keep the issue alive in Brazil, publishing opinion articles and disseminating other information on the subject.

The IBSA (India, Brazil and South Africa) and BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) groupings of so-called emerging or rising powers have gained prominence internationally. A common thread bringing these countries together is the prospect of their forming an alternative to the distribution of power centered on Europe and the United States by promoting an agenda to reform global governance and strengthen the South-South axis. Human rights play a particular role in these two groupings and call for deeper analysis by academic practitioners and others. As mentioned in the Introduction above, although the groupings were not established with a specific mandate to promote and protect human rights (unlike UNHRC), the decisions taken by IBSA and BRICS can nevertheless have a powerful impact on these rights. These groupings also offer opportunities for joint advocacy on topics of interest to civil society in the individual member countries.

According to Itamaraty,

IBSA is a coordinating mechanism covering three emerging countries, three multiethnic and multicultural democracies, which are determined to contribute to building a new international architecture, to speak with one voice on global issues and to enhance their mutual relations in different areas.

(BRASIL, [200–a]).

The subject of human rights, considered to be of core importance to the grouping, has occupied a specific place in the Official Summit Declarations and has been mentioned in the final declarations of all five Presidential Summits to date.11Furthermore, IBSA has shown itself in the past to be able and willing to coordinate policy in areas impacting on human rights, e.g. the group´s reaction to the Middle East crises (the IBSA Mission to Syria in August 2011, the IBSA Declaration on the Gaza Conflict, November 2012, etc.), and the joint positions at the UNHRC (proposal supporting the draft resolution on the right to health and access to medicines at the 12th Session in 2009).

An example of action by Conectas was when a second IBSA mission to Syria was first announced (it did not materialize). Questioning the results of the first mission Conectas was concerned about:

…the announcement of a possible second mission in Syria, since the first showed weak and ineffective outcomes in terms of the victims of human rights violations. The group is concerned that the Syrian government used IBSA to legitimize its actions by averring that Syria is in dialogue and cooperating with countries of the South, without showing proof of genuine commitment to immediately ending the repression.

(CONECTAS 2011, s / w).

In the case of the BRICS, the grouping´s identification with human rights as a key subject is much less clear.12According to Itamaraty “the BRICS is an informal grouping which provides space for its five members to (a) dialogue, identify convergences and consult on various topics and (b) expand contacts and cooperation in specific sectors” (BRASIL, [20–b]).

Although the first four BRICS declarations touched on issues such as the Millennium Development Goals, the human rights issue was addressed only tangentially. The first mention of human rights was in the Final Declaration of the 5th Summit (Durban, 2013), which cited the 20th anniversary of the Vienna Conference and floated the possibility of sectoral cooperation in the human rights area.13 The text also mentioned the need to ensure wideranging humanitarian relief access in the Syrian conflict, thereby significantly expanding the scope of the official statements of the group. The BRICS had hitherto confined themselves to backing the idea of a non-military solution to the conflict and the need to respect Syria´s sovereignty and territorial integrity – all reflecting the standard language previously used to refer to other conflict situations (Afghanistan, Libya, Central African Republic, Iran, etc.).14

On the specific issue of the BRICS approach to the Syrian crisis, Conectas developed an incidence action plan aimed at securing the inclusion in the Declaration of the 5th Summit of a firm statement to underscore the need for unrestricted and secure humanitarian access to all parts of Syria. Prior to the summit, Conectas met Itamaraty officials in Brasilia with a view to familiarizing itself with Brazil’s position on the issue. Conectas also sought to inform the public about the impact that decisions taken jointly by BRICS countries could have on human rights in Brazil and elsewhere. Conectas also joined forces with other humanitarian and human rights organizations in various countries over the case of Syria. These initiatives resulted in the 5th Summit Final Declaration including a specific mention of Syria.15

Brazil´s foreign policy has been marked by a reluctance to prioritize human rights in the context of bilateral relations. This has been the case especially during visits by senior Brazilian government representatives to other countries. One possible explanation for this timidity when confronted with serious violations in countries with which Brazil has diplomatic relations (such as Zimbabwe), is that Brazil does not feel it has moral authority to criticize other nations while human rights abuses continue to be committed in its own territory.

The “glass ceiling” argument has already been put forward by President Dilma Rousseff to justify Brazil´s non-criticism of the notorious violations in two countries which she visited in February 2012 in her capacity as Head of State – Venezuela (PRESIDENTE…, 2011) and Cuba.16 When asked about her failure to raise the issue of political prisoners in Cuban gaols, President Rousseff brushed off the question by commenting that if human rights were on the agenda it would be necessary also to address the situation at Guantánamo Bay. Following on the President´s comment, Conectas requested (two months later) the President to raise human rights, including violations at Guantánamo, with her US counterpart during her official visit to the United States. However according to official information, the subject received no particular emphasis during the visit.17

Conectas is firmly of the opinion that high-level official visits are valuable opportunities that should be used to raise questions related to human rights, given that they are exclusive channels where many other difficult topics such as disagreements over foreign exchange or protectionism are invariably discussed.

Questioned on the case of Cuba, the Brazilian government has stuck to the official line that it awards priority to dealing with human rights issues in multilateral fora.18 Paradoxically, and despite these protestations, very little activity has been observed on the part of the Brazilian government to raise concerns in these multilateral fora about specific cases of human rights violations around the world.19

International cooperation comprises development cooperation initiatives (financial contributions for infrastructure construction, technology transfer through technical and scientific cooperation, etc.) and humanitarian aid (food distribution, provision of doctors, nurses, etc.). Both types of cooperation have an impact on the rights of local populations.

One of the Conectas´research findings in this area is that international cooperation provided by emerging countries is still low in terms of the resources invested. A further issue of concern is that in the case of humanitarian aid it would appear that no clear criteria exist to define which recipients are in greatest need. This problem is abundantly clear in, for example, the case of Syria.

With the continuing deterioration of the Syrian crisis and few prospects for improvement, the UN launched in June 2013 the largest humanitarian call for funds in the organization´s history. An appeal for a total of US$ 4.4 billion for humanitarian assistance programs in and around the country, to serve more than 6.8 million people in urgent need of humanitarian aid, 4.25 million internally displaced and over 1.6 million refugees was launched.

Considering the growing need for humanitarian aid resources for Syria, the economic crisis affecting many traditional donor countries in the North and the process of altering the axis of power from “the Old to the New World”, as certain governments are proud to proclaim, expectations revolved around the emerging countries being willing to make larger financial contributions to the appeal for assistance. However, if we analyze the UN figures, it is now clear that none of these factors led to a significant change in the flow of donations, which continue to be provided mainly by northern hemisphere countries.

According to data from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (UNITED NATIONS, 2013c), of the approximately US$800 million raised for the Regional Response Plan for Syria (RRP) in 2013, 62.9% was donated by the United States, France, Japan, Germany, UK and the EU. Donations from the United States alone accounted for 37.2% of all the funds. Russia, in contrast, donated 1.2% of the total, while China accounted for 0.1%. No RRP donations have yet been verified as forthcoming from emerging countries such as South Africa, India, Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria and Turkey.

Another issue that has concerned Conectas from the bilateral relations standpoint is the use of public resources made available by national development banks to finance the operations of home-based firms abroad. The activities of such firms and the potential for them to be involved in human rights violations are not subject to appropriate social controls.

This situation can also been observed at supranational levels. The announcement, for example, of the creation of the BRICS Bank during the grouping´s 5th Summit in 2013 (in South Africa), flagged up a warning in this regard since no mention was made of transparency criteria and respect for human rights in the Bank´s founding statutes. This amounts to a crucial oversight, particularly since the Bank will be financing major infrastructure projects with significant potential for human rights violations (especially in Africa).

Elsewhere it has been stated that one of the models for the new BRICS Bank would be the BNDES (Brazil´s National Bank for Economic and Social Development), which provided, according to the Bank´s annual report, around US$190 billion in project financing in Brazil and abroad in 2013.

It is worth highlighting that the BNDES has been severely criticized for its lack of transparency and rigour with regard to human rights issues when supplying credit to Brazilian companies operating outside of Brazil. This worrying situation led seven Brazilian civil society organizations, including Conectas, to deliver a joint submission to the UN when it was Brazil´s turn to be subjected, for the second time, to the Human Rights Council Universal Mechanism Review in Geneva.20

This article is not based upon the premise that emerging countries are not sufficiently committed or qualified to make a positive contribution to the protection of human rights internationally. There are nevertheless aspects of their foreign policies that can and should be modified to reveal more clearly the role of human rights issues in their international actions. With the emerging countries achieving a new level of responsibility and visibility on the world stage, it becomes increasingly unacceptable for them to ignore or disregard human rights in their foreign policy agendas.

Various explanations have been put forward for the developing countries´ reluctance to fully embrace the cause of human rights. These involve ideological questions frequently rooted in the idea that emerging countries are loath to reproduce what they regard as the “imperialist” imposition of human rights. On other hand, practical considerations are also thought to hold them back, such as being host to serious human rights violations in their own countries that would leave them open to embarrassing charges of inconsistency between their pronouncements to the world at large and stark reality – the famous “glass ceiling”. In certain developing countries geopolitical considerations also tend to influence attitudes to human rights. This is the case, for example, of India which has to contend with sensitive problems with neighbors in its immediate region (e.g. Pakistan) and which inhibit its government (and governments in similar situations) from taking a more robust line on human rights questions in other parts of the world. These and other causes have been suggested that require cautious and careful analysis. This topic would undoubtedly provide fertile ground for the think tanks devoted to the study of foreign policy which are rapidly evolving in the emerging countries.

On a final note, one particular cause on which human rights organizations can indeed have a degree of influence is to seek to increase the low cost of a foreign policy that fails to promote human rights.

This is one area directly susceptible to intervention by organized civil society: the higher the cost of avoiding transparency and accountability in a country´s international stand on human rights, the greater the political cost will be of a foreign policy that treats human rights as something that is negotiable – a mere bargaining chip in the endless rounds of negotiations between countries. Increasing the political cost of internationally adopted positions that do not necessarily promote and protect human rights is something entirely within the reach of social movements, trade unions and non-governmental organizations.

1. This analysis is shared by: Trubek (2012), Cadernos Adenauer (2012); Alexandroff; Cooper (2010); Piccone; Alinikoff (2012).

2. Although the observations in the article are inspired by the work done by the author with Conectas Human Rights, the positions presented here do not necessarily reflect the institutional views of the organization.

3. The Foreign Ministry’s name refers to the first location of the Ministry, in 19th century Rio de Janeiro, in the house that had once belonged to the Conde de Itamaraty.

4. The Federal Constitution of 1988 states in article 4, Paragraph II that Brazil’s international relations must be governed by ‘the prevalence of human rights.”

5. According to Pillay, hundreds of human rights defenders and dozens of health professionals were arrested in street demos in the country, with some of them brought before the Military Court. Protesters were sentenced to death and life imprisonment. In June 2011, an Independent Commission of Inquiry was set up which found evidence of serious violations committed by the government. Even after the publication of the report and recommendations of this Committee the human rights abuses continued (UNITED NATIONS, 2011).

6. The 27 countries that signed the first joint statement on Bahrain at the 20th Session of the Human Rights Council, were Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Chile, Costa Rica, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Italy, Ireland, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Mexico, Montenegro, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain and Switzerland.

7. The 44 countries that joined signed the second joint statement on Bahrain, at the 22nd Session of the Human Rights Council, were Albania, Andorra, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Botswana, Bulgaria, Chile, Costa Rica, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Mexico, Monaco, Montenegro, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Republic of Korea, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, United States and Uruguay.

8. The human rights situation in Bahrain is still a matter of concern: the government has resorted to legal mechanisms to restrict demonstrations and the right of association, using specific laws to control the activities of civil society organizations. The government has reacted violently against those who oppose these measures and reports of torture and arbitrary detention are still common, even against human rights activists. Additional information about the current and past situation in Bahrain is available from the United Nations (2013a and b), Human Rights Watch (2013a and b) and Amnesty International (2012, 2013) and also on the site of the Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies in the publication entitled “77 International and regional organizations urge the Human Rights Council to stop attempts to undermine UPR” (2013).

9. Compared with other so-called emerging countries, Mexico stands out with its more consistent voting record reflecting its commitment to human rights. According to Bruno Boti, “changes in Mexico´s human rights foreign policy were not a result of pressure exerted by a transnational network of activists, as described by the boomerang and spiral models. The changes were initiated endogenously in government, which sought to anchor the new democratic situation in Mexico abroad through international human rights commitments. In addition the Mexican government sought to ensure and convince international audiences of the credibility of this new attitude adopted by the Mexican State with respect to democratic reforms and human rights” (BERNARDI, 2009, p. 5).

10. The Human Rights Commission of the United Nations was replaced by the Human Rights Council in 2006. To learn more about the creation of the HRC, see Lucia Nader´s article in Issue no. 7 of Sur Journal.

11. At the first Brasilia Summit in 2006, the official text stated that: “India, Brazil and South Africa, elected to the newly-formed Human Rights Council of the United Nations […] share a common vision for reaffirming the universality, indivisibility, interdependence and interrelatedness of all human rights and fundamental freedoms, including the implementation and operationalization of the Right to Development and the special protection of the rights of vulnerable groups” (paragraph 16). The text also mentions that countries look kindly upon the adoption of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (paragraph 17). At the following Summit held in 2007 in Pretoria, the question of the right to development is mentioned again, and countries equally affirm their commitment to the Council and the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) mechanism of that body (paragraph 14). In 2008, in Delhi, the group again refers to the UN Human Rights Council and states that the work of the group “must develop without politicization, double standards and selectivity, and promote international cooperation on this subject” (paragraph 22). The leaders also emphasize the importance of a sectional dialogue around the subject aimed at mutual benefit to be secured from the protection and promotion of human rights (paragraph 23). At the 4th Summit in Brasilia in 2010, the member governments reaffirmed the high priority given to human rights and the importance of cooperation in this area (paragraph 9). Specific mention is made of the issue of racism, racial discrimination and xenophobia as an area deserving attention (paragraph 10). They also acknowledge the adoption of a resolution by the HRC proposed collectively by the group members in the context of access to medical drugs (UNITED NATIONS, 2009). Finally, at the most recent Summit in Pretoria (2011), the group repeats the “imperative need for the international community to recognize and reaffirm the centrality of the Human Rights Council” (paragraph 39). The same paragraph also reaffirms that “leaders recognize that development, peace and security and human rights are interlinked and mutually reinforcing.” Furthermore they reaffirm their commitment to the Durban Declaration and its Plan of Action for the achievement of the World Conference against Racism, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance (WCAR) + 10, held that year. In paragraph 41, the need is highlighted to enhance cooperation in international human rights bodies and to share good practices in this area.

12. At the Delhi Summit (2012), the group claimed to be a “platform for dialogue and cooperation […] for the promotion of peace, security and development in a multipolar, interdependent and increasingly complex and globalized world” (Delhi Declaration, 2012, paragraph 3).

13. “We welcome the 20th Anniversary of the World Conference on Human Rights and the Vienna Declaration and Plan of Action and agree to examine possibilities for cooperation in the area of human rights (paragraph 23).”

14. “Due to the deteriorating humanitarian situation in Syria, we urge all parties to allow and facilitate the immediate, safe, full and unrestricted humanitarian organizations to all who need access to care. We urge all parties to ensure the safety of humanitarian workers” (paragraph 26).

15. Learn more about the action in Conectas http://www.conectas.org/pt/acoes/politica-externa/noticia/cupula-dos-brics-termina-com-avanco-sobre-a-siria-e-incertezas-sobre-novo-banco. Last accessed on: Nov. 2013.

16. The allegation that the existence of human rights problems in Brazil disqualifies it from making any criticism of major assaults on, and abuses of, freedoms in the world. An example of this argument is shown during President Rousseff´s visit to Cuba (LIMA 2012).

17. Conectas made ??use of the channel opened up by the Foreign Ministry to engage with society via Twitter regarding the President´s official visit to the US in 2012. See Brasil (2012b).

18. Examples of Dilma Rousseff´s statements in this vein are: “I believe that human rights cannot be the object of political struggle, and I will not use political struggle to that end because I do not consider that there is only one country or group of countries that violates human rights. Therefore I would like to discuss this issue always multilaterally, because I know that this issue is exploited for political purposes” (UOL, 2012). At Harvard during the visit to the United States. Finally, “Who throws the first stone has a glass ceiling. We have ours in Brazil. That´s why I agree to talk about human rights within a multilateral perspective” (FELLET, 2012). During a press conference in Cuba.

19. The monitoring done by Conectas of Brazil’s role in the UN Human Rights Council, the main multilateral body on human right questions, reveals that Brazil continues to award priority to the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) mechanism for addressing issues in other countries. While this is certainly a tool that should be strengthened, it must be remembered that each of the UN Member States submit themselves to the UPR once every four and a half years. Human rights crises need to be dealt with promptly and the HRC has the clear mandate to do so. Brazil should concentrate on strengthening the international community’s ability to react robustly against violations wherever they occur so that its oft-stated preference for dealing with violations in multilateral spaces and its harsh criticism of HRC selectivity are less contradictory. For more information about the UPR see Conectas Direitos Humanos (2012).

20. Conectas Human Rights on Business and Human Rights submission for the second appearance by Brazil in the Universal Review of Human Rights, including the question of the National Development Bank of Brazil. See Agere et al. (2011).

Bibliography and other sources

AGERE et al. 2012. Universal Periodic Review 2nd Cycle–Brazil Submission by other relevant stakeholders about: Brazilian obligations to address human rights violations perpetrated by companies, November 28, 2011. Available at: http://www.conectas.org/arquivos-site/SubmissionUPRBrazil_BusinessandHR_Conectasanpartners.pdf. Last accessed on: 25 Aug. 2013.

ALEXANDROFF, Alan S.; COOPER, Andrew F. (eds). 2010. Rising States, Rising Institutions: Challenges for Global Governance. Washington: Brookings Institute.

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL. 2012. Wire, v. 42, n. 2, march/april. Available at: http://www.amnesty.org/sites/impact.amnesty.org/files/Wire_MarApr_Web.pdf. Last accessed on: 25 Aug. 2013.

_______. 2013. Bahrain: New decrees ban dissent as further protests organized. 7 august 2013. Available at: http://www.amnesty.org/en/news/bahrain-new-decrees-ban-dissent-further-protests-organized-2013-08-07. Last accessed on: 25 Aug. 2013.

BERNARDI, Bruno B. 2009. O processo de democratização e a política externa mexicana de direitos humanos: uma análise ao longo de duas décadas (1988-2006). Resumo. 2009. Dissertação (Mestrado)–Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo.

BRASIL. 1988. Constituição (1988). Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil. Brasília, DF: Senado Federal.

_______. [20—a]. Ministério das Relações Exteriores. IBAS: Índia, Brasil e África do Sul. Available at: http://www.itamaraty.gov.br/temas/mecanismos-interregionais/forum-ibas. Last accessed on: Nov. 2013.

_______. [20—b]. Ministério das Relações Exteriores. BRICS: Brasil, Rússia, Índia, China e África do Sul. Available at: http://www.itamaraty.gov.br/temas/mecanismos-interregionais/agrupamentobrics. Last accessed on: Nov. 2013.

_______. 2012a. Intervenção de Sua Excelência, Ministra de Estado Chefe da Secretaria de Direitos Humanos da Presidência da República Federativa do Brasil, Ministra Maria Nunes do Rosário, Segmento de Alto Nível, Décima Nona Sessão Regular do Conselho de Direitos Humanos, 27 de fevereiro. Available at: www.pucsp.br/ecopolitica/downloads/seguranca/Discurso_Ministra_Maria_Rosario_Onu_Direitos_Humanos_fev_2012.pdf. Last accessed on: 20 Aug. 2013.

_______. 2012b. Ministério das Relações Exteriores. Assessoria de Imprensa do Gabinete. Entrevista via Twitter com o Porta-Voz do Itamaraty sobre as relações Brasil–Estados Unidos, Brasília, 5 de abril de 2012. Available at: http://bit.ly/entrevista-mre-twitter. Last accessed on: Nov. 2013.

________. 2013. Discurso do Senhor Ministro de Estado das Relações Exteriores por ocasião da 22ª Sessão do Conselho de Direitos Humanos das Nações Unidas, Segmento de Alto Nível, 25 de fevereiro. Available at: extranet.ohchr.org/sites/hrc/HRCSessions/RegularSessions/22ndSession/OralStatements/Brazil%20Meeting%203.pdf. Last accessed on: 20 Aug. 2013.

CADERNOS ADENAUER. 2012. Potências emergentes e desafios globais. Rio de Janeiro: Fundação Konrad Adenauer, ano XIII, n. 2, dezembro.

CONECTAS DIREITOS HUMANOS. 2011. Conectas solicita informações ao governo brasileiro sobre direitos humanos na Síria, 19 de outubro de 2011. Available at: http://www.conectas.org/pt/acoes/politica-externa/noticia/conectas-solicita-informacoes-ao-governo-brasileiro-sobre-direitos-humanos-na-siria. Last accessed on: 25 Aug. 2013.

_________. 2012. O Brasil na RPU em 2012 (2° ciclo). Available at: http://www.conectas.org/pt/acoes/politica-externa/noticia/3-o-brasil-na-rpu-em-2012-2o-ciclo. Last accessed on: Ago. 2013.

________. 2013. Foreign Policy and Human Rights: Strategies for Civil Society Action. A view through the experience of Conectas in Brazil. São Paulo. June. Available at: http://conectas.org/arquivos/editor/files/CONECTAS%20ing_add_LAURA.pdf. Last accessed on: Aug. 2013.

FELLET, João. 2012. Em Cuba, Dilma diz que violações de direitos humanos ocorrem em todos os países. BBC Brasil, 31 de janeiro, 2012.

FONSECA J., Gelson. 2012. BRICS: Notas e questões. In: FUNAG. O Brasil, os BRICS e a Agenda Internacional. Brasília. Available at: http://www.funag.gov.br/biblioteca/dmdocuments/OBrasileosBrics.pdf. Last accessed on: Nov. 2013.

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH. 2013a. Bahrain: New Associations Law Spells Repression, 20 june 203. Available at: http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/06/20/bahrain-new-associations-law-spells-repression. Last accessed on: 25 Aug. 2013.

_______. 2013b. Bahrain: Detained Activists Allege Torture. 15 may 2013. Available at: http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/05/14/bahrain-detained-activists-allege-torture. Last accessed on: 25 Ago. 2013.

JOINT NGO Letter to State Delegations at the United Nations Human Rights Council: Call for Joint Action on Bahrain at the 20th Session of the United Nations Human Rights Council. 2012. Conectas Direitos Humanos. 22 june 2012. Available at: http://www.conectas.org/arquivos-site/2012_06_21%20-%20Carta%20-%20Joint_Call_Bahrain%20-%20HRC%20Delegations%20-%20HRCnet%20-%20EN.pdf. Last accessed on: 29 Aug. 2013.

JOINT NGO Letter to the Member States of the United Nations: Supporting Human Rights Accountability and Reform in Bahrain at the UN Human Rights Council. 2013a. Conectas Direitos Humanos. 14 february 2013. Available at: http://www.conectas.org/arquivos-site/Joint_Bahrain_Letter_%20HRC%2022_%20FINAL_14_02_2013.pdf. Last accessed on: 29 Aug. 2013.

JOINT Statement on the OHCHR and the human rights situation in Bahrain. 2013b. Conectas Direitos Humanos. Setembro de 2013. Available at: http://www.conectas.org/arquivos/editor/files/ANEXO%20IX_%20Statement%20on%20the%20OHCHR%20and%20the%20human%20rights%20situation%20in%20Bahrain%20(3).pdf. Last accessed on: Nov. 2013.

LIMA, Luciana. 2012. Dilma evita discutir direitos humanos e diz que Brasil tem ‘telhado de vidro’. Carta Capital, São Paulo, 31 de janeiro de 2012, Internacional.

PICCONE, Ted; ALINIKOFF, Emily. 2012. Rising Democracies and the Arab Awakening: Implications for Global Democracy and Human Rights. Washington D.C.: Brookings, 2012.

PRESIDENTE Dilma Rousseff visita Venezuela. 2011. Conectas Direitos Humanos, 01 dezembro 2011. Available at: http://www.conectas.org/pt/acoes/politica-externa/noticia/presidente-dilma-rousseff-visita-venezuela. Last accessed on: 25 Aug. 2013.

REPÓRTER BRASIL. 2011. BNDES e sua política social e ambiental: uma crítica da perspectiva da sociedade civil, p. 2, fevereiro. Available at: http://www.reporterbrasil.org.br/documentos/BNDES_Relatorio_CMA_ReporterBrasil_2011.pdf. Last accessed on: 26 Aug. 2013.

77 INTERNATIONAL and regional organizations urge the Human Rights Council to stop attempts to undermine UPR. 2013. Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies, 10 june 2013. Available at: http://www.cihrs.org/?p=6805&lang=en. Last accessed on: 25 Aug. 2013.

SOUTH AFRICA. 2013. Draft statement by Deputy Minister Ebrahim Ebrahim, South African Deputy Minister of International Relations and Cooperation at the High-Level Segment of the 22nd Session of the United Nations Human Rights Council, 25 february. Available at: https://extranet.ohchr.org/sites/hrc/HRCSessions/RegularSessions/22ndSession/OralStatements/South%20Africa.pdf. Last accessed on: 22 Aug. 2013.

TRUBEK, D. (2012). Reversal of Fortune? International Economic Governance, Alternative Development Strategies, and the Rise of the BRICS. Available at: http://www.law.wisc.edu/facstaff/trubek/eui_paper_final_june_2012.pdf. Last accessed on: 29 Aug. 2013.

UNITED NATIONS. 2009. Promotion and Protection of all Human Rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development, Resolution A/HRC/RES/12/24, 12 october 2009.

_______. 2011. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Pillay deeply concerned about dire human rights situations in Bahrain, 5 May. Available at: http://www.ohchr.org/en/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=10985&LangID=E. Last accessed on: 29 Aug. 2013.

_______. 2013a. Statement attributable to the Spokesperson for the Secretary-General on Bahrain. Latest Statements, 18 July. Available at: http://www.un.org/sg/statements/index.asp?nid=6974. Last accessed on: 25 Aug. 2013

_______. 2013b. UN Human Rigths. Press briefings notes on Qatar and Bahrain, 8 January. Available at: http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=12916&LangID=E. Last accessed on: 25 Ago. 2013.

_______. 2013c. High Comissioner for Refuges. Syria Regional Response Plan – RRP, 2013 Income as of 19 December 2013. Available at: http://www.unhcr.org/syriarrp6/. Last accessed on: Nov. 2013.

UOL. 2012. Em Harvard, Dilma fala sobre Venezuela, corrupção, Copa do Mundo e diz que queria ser bombeira, 10 de abril, Internacional.