new approaches and classic tensions in the inter-american human rights system

The Inter-American System of Human Rights (ISHR), during the last decade, has influenced the internationalization of legal systems in various Latin American countries. This led to the gradual application of ISHR jurisprudence in constitutional courts and national supreme courts, and most recently, in the formulation of some state policies. This process resulted in major institutional changes, but there have been problems and obstacles, which have led to some setbacks. The ISHR finds itself in a period of intense debates, which seek to define thematic priorities and the logic of intervention, in the context of a new regional political environment of deficient and exclusionary democracies, different from the political landscape in which the ISHR was born and took its first steps. This article seeks to present an overview of some strategic discussions about the role of the ISHR in the regional political sphere. This article suggests that the ISHR should in the future intensify its political role, by focusing on the structural obstacles that affect the meaningful exercise of rights by the subordinate sectors of the population. To achieve this, it should safeguard its subsidiary role in relation to the national justice systems and ensure that its principles and standards are incorporating not only the reasoning of domestic courts, but the general trend of the laws and governmental policies.

The Inter-American System of Human Rights (ISHR), during the last decade, has influenced the process of internalization amongst the legal systems in various countries in Latin America. During this period, more countries have accepted the jurisdiction of the Inter-American court (such as Mexico and Brazil) and have given the American Convention constitutional status, or higher, compared to the laws of their judicial systems. Lawyers, judges, legal practitioners, officials and social activists have learned much about the workings of the ISHR and have begun to use it in a manner that is no longer extraordinary or selective. In addition, they have begun to cite its decisions and ground arguments in its precedents both in the local courts and in the public policy debates. This led to the gradual application of ISHR jurisprudence in constitutional courts and national supreme courts, and most recently, although to a lesser degree, in the formulation of some state policies. This process of incorporating international human rights law at the national level led to important institutional changes.

For example, the legal standards developed by the jurisprudence of the Inter-American Commission (IACHR or Commission) and of the Inter-American Court (IACHR Court or Court) about the invalidity of the amnesty laws pardoning gross violations of human rights, gave legal support to the transparency of trials against those charged with crimes against humanity, in Peru and Argentina. The standards set in the case Barrios Altos against Peru have played a decisive role in invalidating the self-amnesty law of the Fujimori regime, and in supporting the prosecution of crimes committed during his administration (PERÚ, Barrios Altos vs. Perú, 2005), but the decision in the case has had a cascading effect and has influenced the legal arguments of Argentine courts by invalidating laws of obedience (ARGENTINA, Simón, Julio Héctor et al, 2005). Inter-American jurisprudence is also present, although to a lesser extent, in recent decisions of the Chilean appellate courts.1 This is also relevant to the debates about reducing the penalties in the peace process with paramilitary groups in Colombia, as well as the political and judiciary treatment of the remaining issues of transitional justice in Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Paraguay and Uruguay. Recently, cases alleging crimes against humanity that were committed during the “Cold War” have been brought before the Court regarding Brazil (IACHR, Julio Gomez Lund et al vs. Brazil, 2009c), Bolivia (IACHR, Renato Ticona Estrada et al vs. República de Bolívia, 2007b) and Mexico (IACHR, Rosendo Radilla Pacheco vs. México, 2008b), which has influenced local political and legal discussions.

This process, however, is not linear. It encounters problems and obstacles and has also suffered some setbacks. The ISHR, furthermore, finds itself in a period of intense debates that seek to define its thematic priorities and logic of intervention, in a new regional political environment of deficient and exclusionary democracies, different from the political landscape in which it was born and took its first steps, with the South American dictatorships in the 1970’s and the Central American armed conflicts of the 1980’s.

This article seeks to present an overview of some strategic discussions that take place both within the Inter-American organs, and the human rights community, about the role of the ISHR in the regional political arena.

First, we will try to identify the role of the ISHR organs in three distinct historical moments, presenting at each point the thematic priorities and main l strategies for intervention. In this way, we will describe the present role of the ISHR, its status as an alternative to democratic systems, and its strategic use by civil society on the local and international level, and by governments and state agencies.

In the article’s second part, we will describe the expansion of the ISHR’s agenda into social and institutional issues, and present the recent developments in structural equality and the recognition of special rights for subordinate groups. In the second part, we will also call attention to the approach to certain human rights conflicts in the region, such as evidence of systemic racism, violence and exclusion, and we will relate this structural analysis to the contextualization of individual cases arising out of the massive human rights violations perpetrated during the dictatorships.

Finally, in the third part of the article, we will briefly present a preliminary agenda for discussion of some of the ISHR’s challenges, especially the review of its mechanisms for remedies, the procedures for implementing its decisions, the procedural rules for the litigation of multi-party cases, as well as the complex, tense relationship between the ISHR and the national judicial systems.

Undoubtedly, the roles of the system’s organs, of both the Commission and the Court, have changed in light of the changing political landscapes in the Americas.

At the beginning, the ISHR dealt with cases involving massive and systematic human rights violations perpetrated under systems of state terrorism, or in the context of violent internal armed conflict. Its role was, in short, a last resort of justice for the victims of these violations, as they could not look to national systems of justice that had been devastated or corrupted. In this initial phase of political gridlock within the member nations, the Commission’s Country Reports served to document situation with technical precision, to legitimate complaints by victims and their organizations, and to expose and erode the image of the dictators in the local and international spheres.

Later, during the post-dictatorial transitions in the 1980’s and the beginning of the 1990’s, the ISHR had a broader purpose, as it sought to monitor the political processes aimed at dealing with the authoritarian past and its scarring of democratic institutions. During this period, the ISHR began to delineate core principles about the right to justice, truth, and reparations for gross, massive, and systematic human rights violations. It set limits on the amnesty laws. It laid the foundation for the strict protection of freedom of expression and the prohibition on prior restraint. It forbade the military courts from judging civilians and hearing human rights cases, limiting the space in which the military could operate, as they continued to have veto power during the transition and sought impunity for past crimes. It protected habeas corpus, procedural due process, the democratic constitutional order and the division of state powers, in light of the latent regression possibility to an authoritarian state and the abuses of states of emergency (IACHR COURT, 1986, 1987a, 1987b).2 It interpreted the scope of the limitations imposed by the Convention as regards the death penalty, invalidating it for minors and the mentally ill, allowing it to be applied only in cases where a crime was committed, and establishing strict standards of due process, as a safeguard against the arbitrariness of the courts in imposing the death penalty. It also addressed regional social issues which showed a discriminatory bias by, for example, affirming equality before the law for women asserting their familial and matrimonial rights, and the rights of inheritance for children born out of wedlock, which the American civil codes still considered “illegitimate.”

During the 1990’s, moreover, it also confronted with firmness state terrorist regimes, such as the Peruvian regime of Alberto Fujimori, documenting and denouncing violations that had also been committed in South America in the 1970’s, such as systematic forced disappearances and torture, and the subsequent impunity for these state crimes. It was also an important player in addressing the gross human rights violations and violations of international humanitarian law committed in the context of internal armed conflict in Colombia.

The present regional landscape is undoubtedly more complex. Many countries in the region made it through their transitional periods, but were not able to consolidate their democratic systems. These representative democracies have taken some important steps, by improving their electoral systems, respecting freedom of the press, the abandonment of political violence; but they show serious institutional deficiencies, such as an ineffective judicial system and violent police and prison systems. These democracies also have alarming levels of inequality and exclusion, which cause a perpetually unstable political climate.

In this new climate, the ISHR organs have sought not only to compensate the victims in individual cases, but to establish a body of principles and standards, with the objective of influencing the equality of these democratic processes and strengthening the main domestic rights protection mechanisms. At this stage, the ISHR faces the challenge of improving the structural conditions that guarantee the realization of rights at the national level. This approach takes as a given the subsidiary character of the international protection mechanisms in light of the rights guarantees made by the states themselves. It recognizes the clear limits of international involvement and, at the same time, maintains the necessary degree of autonomy from national political processes, to attain higher levels of efficacy and observance of human rights.

The ISHR thus interprets certain procedural rules that define the criteria for its intervention in such a way that the autonomy of the states is respected. For example, there is a rule that requires “previous exhaustion” of domestic remedies, as well as the rule of the “fourth recourse,” by which the ISHR refrains from reviewing the decisions of the national courts in cases not directly governed by the Convention, and satisfying procedural due process guarantees.

The first rule, of “prior exhaustion of domestic remedies,” although it is procedural in nature, is a key factor in understanding the working dynamic of the Inter-American system and especially its subsidiary role. By requiring that parties exhaust all remedies available in the state’s national judicial system, it gives each state the opportunity to resolve conflicts and remedy violations before the matter is considered in the international arena. The scope of this rule in the jurisprudence of the ISHR’s organs defines the degree to which it is willing to intervene as an international mechanism, based on the competence and effectiveness of the national judicial system.

The second rule, known as the “fourth recourse,” functions as a kind of deference to national judicial systems, because it allows them the autonomy to interpret local norms and decide individual cases, subject to the exclusive condition that they respect procedural due process guarantees established in the Convention.3

The ISHR has also come to recognize the new political environment of constitutional democracies in the region, showing deference to the member-states on how certain sensitive issues are defined, such as the design of electoral systems in accordance with each social and historical context, and always respecting the democratic l exercise of political rights.4

In some cases, moreover, the IACHR in its reviews has paid special attention to the arguments developed by the state’s appellate courts, which have applied the provisions of the same Convention, or analyzed the same issues with their own constitutional parameters. It is not a matter of deference in the strict sense, but a kind of special consideration given to certain domestic court decisions and the arguments presented therein, which are given substantial weight as the IACHR conducts its own review of the case. This kind of argument has been considered in the analysis about the reasonableness of domestic laws that imposed restrictions on fundamental rights. This was the case, for example, when arguments made by local courts were considered in analyzing the proportionality of damages awarded in a defamation case, to determine whether the right to a free press had been violated (IACHR, Dudley Stokes vs. Jamaica, 2008a). In addition, the IACHR considered a domestic court decision about the reasonableness of a social security reform, to determine if the reform complied with parameters of proportionality and progressiveness, and thus if there were legitimate restrictions on social rights (IACHR, Asociación Nacional de Ex Servidores del Instituto Peruano de Seguridad Social y otras vs. Perú, 2009d).

But in the new regional political landscape, in addition to a change in approach, it is also possible to identify a change in agenda.

As mentioned earlier, during the transitional phase, the ISHR contributed to some institutional debates, such as the subordination of the armed forces to civilian control and its involvement in internal security matters, and the scope of the privileges and powers of the military judicial system. These subjects had a direct connection with how past violations were treated, as it involved the military’s ability to pressure and veto during the transitional period. In the aftermath of the transitions, the institutional agenda has grown considerably in terms of the kind of issues that come to the ISHR’s attention.

A focuspoint of the ISHR’s new agenda is to address issues relating to the functioning of judicial systems, which have an impact on or connection with the promotion of human rights. This includes procedural due process guarantees of the accused in criminal proceedings, as well as the right of certain victims, harmed by structural problems relating to the impunity of crimes committed by the state (by police and prison officials), to have equal access to the justice system. Strategies to combat organized crime and international terrorism have incorporated some discussions from the transitional period relating to the administration of justice, such as the debate about the jurisdiction of military courts. In that sense, it has become central in monitoring public security policies. It also guarantees the independence and impartiality of the courts and safeguards various issues related to the full protection of due process and the right to judicial protection, and to the judicial protection of social rights.

Another line of institutional issues considered by the ISHR in the post-transition era relates to the preservation of the democratic public sphere in the countries of the region. These issues include freedom of expression, freedom of the press, access to public information, freedom of assembly and association, freedom of protest and the gradual ripening of issues relating to equality and due process of law in electoral matters.

Moreover, a priority of the ISHR’s agenda at this stage are the new demands for equality made by groups and collectives, relevant to the institutional issues discussed above, as they include marginalized and excluded sectors of society whose rights and ability to participate and express themselves are affected, who suffer from institutional or social patterns of violence, obstacles in accessing the public sphere, the political system, or social or judicial protection. This question will be explored in Sections 4 and 5.

In addition to broadening the agenda, in this third stage a change in how the ISHR intervenes, and the impact of its decisions at the local level can be observed.

The ISHR’s jurisprudence has had a considerable impact on the jurisprudence of the national courts that apply the norms of international human rights law. It is important to consider that decisions made by the organs of the system in a particular case, in interpreting the treaties applicable to the conflict, have a heuristic value that transcends the victims affected in this process. This international jurisprudence, moreover, is often used as a guide for judgments issued by national courts, which seek to prevent countries from being named on petitions and eventually convicted in these international forums. This globalization of human rights standards, while not attaining the same level of development through the entire region and while subject to the precariousness of the national systems, has undoubtedly had a positive effect on the transformation of these same judicial systems, and has generated greater attention amongst the state authorities in regard to the ISHR’s developments. Consequently, the jurisprudence established by the Commission and especially by the Court, has brought about several changes in the jurisprudence of the countries in the region on issues related to the weak and deficient institutions of Latin American democracies. Take, for example, the case about the decriminalization of defamation and the criticisms from the press, access to public information, and limits on the criminal prosecution of peaceful public demonstrations. Other issues include setting limits and objective conditions for the use of pretrial detention, the detention powers of the police and their use of public force; the determination of guidelines for a separate justice system for minors, the right to appeal a conviction to a higher court, the participation of victims of state crimes in judicial proceedings. Finally, there are the cases involving the recognition of procedural due process in the administrative and judicial review of administrative acts, as well as basic safeguards in the process of removal of judges, amongst other issues of great importance for the functioning of institutions and constitutional order in the states (MENDEZ; Mariezcurrena, 2000, ABRAMOVICH, cattle; COURTIS, 2007).

The influence of the ISHR, however, does not limit itself to the impact of its jurisprudence on the jurisprudence of local courts. Another important avenue for strengthening democratic institutions in the states stems from the ISHR’s ability to influence the general direction of some public policies, and in the formulation, implementation, evaluation and oversight of those same policies. It is thus common that individual decisions adopted in one case generally impose upon states the obligation to formulate policies to redress the situation giving rise to the petition, and the duty to address the structural problems that are at the root of the conflict analyzed in the case.

The imposition of these positive obligations is generally preceded by a review of the legal standards, implemented policies, or lack of action (omission) of the state. These obligations may include changes in existing policies, legal reforms, the implementation of participatory processes to develop new public policies and often the reversal of certain patterns of behavior that characterize the actions of certain state institutions that promote violence. This includes police violence, abuse and torture in prisons, the inaction of the state when confronted with domestic violence, policies of forced displacement of the population in the context of armed conflicts, and massive displacement of indigenous peoples from their ancestral lands.

Furthermore, in the context of individual cases, the ISHR, especially the Commission, promotes friendly settlements or negotiations between the petitioners and the states, where the latter will often agree to implement these institutional reforms or create mechanisms to consult with civil society in the formulation of policy. Consequently, in the context of amicable solutions, some states have changed their laws. For example, they repealed the defamation provisions that allowed the criminalization of political criticism; created procedures to confirm the whereabouts of disappeared persons; implemented massive programs of reparations for victims of human rights violations or collective reparation programs for communities affected by violence; implemented public programs to protect victims, witnesses, and human rights defenders, reviewed criminal cases in which defendants had been convicted without due process, or reviewed the closing of criminal cases in which state agents had been fraudulently acquitted of human rights violations; reformed civil code rules that discriminate against children born out of wedlock; or civil code rules that discriminate against women in their marital rights; or those that implement quota laws for women in elections, or laws on violence against women; implement protocols for the execution of non-punishable abortions, or abolished immigration laws that affected the civil rights of immigrants.

The IACHR also makes recommendations about public policy in its country reports. In these reports, it analyzes specific situations where violations have taken place and makes recommendations to guide state policies based on legal standards.5

The Commission may also issue thematic reports that cover topics of regional interest or of interest to several states. This type of report has enormous potential to set standards and principles and to address situations involving the collective or structural problems that may not be adequately reflected in individual cases. They also offer a clearer promotional perspective than the country reports, which are usually seen as publicity for the states before the international community and local groups. The process of preparing these thematic reports, in turn, allows the Commission to dialogue with local and international engaged stakeholders, collect the opinions of experts, agencies and international financial institutions, OAS political and technical bodies, and to establish ties with officials ultimately responsible for generating policies in the studied fields.6

Finally, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights may issue advisory opinions, which are used to examine specific problems that go beyond the contentious cases, and set the scope of state obligations deriving from the Convention and other human rights treaties applicable at the regional level, such as the legal status of migrant workers, and the human rights of children and adolescents. In these advisory opinions, the Court has sometimes tried to establish legal frameworks for policy development. For example, Advisory Opinion 18 seeks to define a set of principles that should orient states’ immigration policies, in particular the recognition that undocumented immigrants should enjoy certain basic social rights. In Advisory Opinion 17, the Court seeks to influence policies aimed at imposing limits on criminal provisions directed at children.

At the same time, the ISHR, both the Commission and the Court, have gradually become a privileged arena of civil society activism, which has produced innovative strategies to make use of the international repercussion of the cases and situations denounced at the national level, in the so-called boomerang strategies (NELSON; DORSEY, 2006, RISSE; SIKKINK, 1999, SIKKINK, 2003).

Social organizations have used the international arena not only to denounce violations and make visible certain questionable state practices, but also to attain a measure of status that allows them to dialogue with governments and their partners from a higher plane, and to invert the power relationship and alter the dynamics of political processes. It has sometimes facilitated the opening of spaces for social participation and influence in the formulation and implementation of policies, and the development of institutional reforms. These social organizations have also frequently incorporated the legal standards set by the ISHR as a parameter to assess and monitor state actions and policies, and sometimes to challenge them in national courts or through the use of local and international opinion.

In Latin American countries, many human rights organizations and other socially minded organizations seek to vindicate rights, such as feminist, citizen, environmental, and consumer rights organizations, amongst others; in addition to monitoring state action, they have incorporated new strategies of dialogue and negotiation with governments, to influence the direction of its policies and attain transformations in the functioning of public institutions. This change of perspective seeks to incorporate to the traditional work of denouncing violations, a preventative and promotional measure intended to curb abuses.

In this way, the community of ISHR users has grown considerably and has become more varied and complex. The ISHR has begun to be utilized much more frequently by the local social organizations, and not only by the traditional international organizations that helped shape it in its early days, or by those that have specialized in using its mechanisms. Some of the more successful cases in terms of their social impact have been sustained and promoted by “multi-level” coalitions or alliances that have the capacity to act in different spheres both locally and internationally. In general, these coalitions are formed by regional or international organizations that have experience in using the ISHR, and local organizations with the capacity for social mobilization, dialogue and influence on public opinion and government policies. This type of alliance has engendered an improvement in the articulation of strategies in the international arena, as well as those used on the local level.

At the same time, many local organizations have gradually gained sufficient experience to act on their own before the ISHR, and have occasionally forged alliances amongst their peers in other countries in the region to promote regional issues of common interest at the ISHR such as police brutality, access to public information and violence against women (MACDOWELL SANTOS, 2007). For example, a network of organizations specializing in issues involving police violence and the criminal justice system has suggested that the Commission involve itself in preparing a thematic report on citizen security and human rights, setting clear standard to guide democratic security policies throughout the region. The influence of the network of social organizations has also resulted in a recent report about the situation of human rights defenders developed by the Commission, as well as how to follow up on the Commission’s recommendations in the States. A network of non-governmental organizations and community media advocates that the IACHR adopts a series of fundamental principles for the regulation of broadcasting.

In addition to legal public interest organizations, which generally represent victims or groups of victims, certain kinds of cases before the ISHR often involve community organizations that also are part of networks or alliances with the legal organizations, to promote IACHR cases, thematic hearings or reports. The work of the IACHR rapporteurs on the rights of indigenous peoples and racial discrimination has considerably expanded the use of the ISHR by Afro-American and indigenous communities. It has also increased the involvement of unions who have an alliance with human rights organizations, raising issues concerning the freedom to unionize, and the right to fair labor practices and pensions.

In countries such as Argentina and Peru where the ISHR is better known, private attorneys have begun using the international system as a new forum for litigating various issues, including those relating to delays in processing pension benefits, the application of emergency laws, and the due process rights of the accused in criminal proceedings.

But the ISHR has also been actively used by some states or government agencies with expertise in human rights to shed light on certain issues and promote national and regional agendas. These processes have led to the gradual formation of a specialized state bureaucracy to manage these issues, which have tended to influence some aspects of public management, such as human rights secretariats and commissions, specialized divisions in Foreign Ministries, ombudsmen, human rights attorneys, public defenders and special prosecutors, among others. Occasionally, when governments have clear policies on these issues, a case at the ISHR generally is considered an opportunity to shape policy in the areas of governmental interest, to overcome resistance in the state itself or other social sectors. This can be clearly seen in some amicable settlements that induced change in legislation and national policies (TISCORNIA, 2008). Occasionally, the petitioners are independent public agencies that litigate and sometimes negotiate on behalf of the government. Public defenders’ offices have become a frequent and important player at the ISHR.

Some states, for example, have used, the Court’s advisory opinions to promote human rights issues that occupy a central role in their foreign policy, such as the protection of its nationals who migrate to developed l countries. For example, Mexico promoted the ISHR’s pronouncements about consular assistance in death penalty cases and those involving the labor rights of undocumented immigrants, persuading the United States to present itself before the Court as Amicus Curiae to defend the tenets of its own policies. Recently the Argentine government, in conjunction with private social organizations, promoted a discussion about the legality of having states litigating before the Court, appointed judges to it on an ad hoc basis, and on the potential impact on the principle of impartiality. In the last three years, there have also been two interstate lawsuits for the first time since the American Convention came into force.7

The number of public officials, judges, public defenders, prosecutors and judicial personnel that have come before the Inter-American Commission and Court of Human Rights seeking urgent protection against threats, intimidation and violence in retaliation for carrying out their duties has also grown significantly. These conditions break the classic pattern of the ISHR protecting victims from the abuses of authoritarian and monolithic states, and show that the ISHR nowadays is more complex in the execution of its duties, confronting democratic states that express internal ambiguities, disputes and contradictions.

This gradual change in the ISHR’s role in the new political environment was accompanied by a gradual change in its agenda of issues. As has been shown, however, some of the traditional issues have been neither addressed nor displaced, as in the case of transitional justice. The new agenda is characterized by the incorporation of new issues, which coexist with traditional issues.

In recent years, the ISHR has increasingly confronted an agenda tied to the problems stemming from inequality and social exclusion. After enduring complicated periods of transition, Latin American democracies find themselves threatened by the sustained increase in social inequality and the exclusion of vast portions of the population from the political system and the benefits of development, which imposes structural limitations on the exercise of social, political, cultural and civil rights.

The problems of inequality and exclusion are reflected in the degradation of certain institutional practices and the deficient functioning of the democratic states, which engenders new forms of human rights vulnerability, often related to the practices of authoritarian governments from past decades. The issue is not that the states plan a systematic violation of human rights, nor that the upper tiers of government seek deliberately to infringe upon fundamental rights, but rather that states, with their legitimately elected officials, are not capable of reversing and impeding arbitrary practices committed by their own agents, nor of ensuring effective mechanisms of accountability, on account of the precarious functioning of their judicial systems (PINHEIRO, 2002). The social sectors that live under conditions of structural inequality and exclusion are the primary victims of this institutional deficit, which is reflected in some of the cases on the ISHR’s docket: police violence marked by social or racial bias, torture and overpopulation in prisons, whose victims are usually young persons from the lower classes; a generalized practice of domestic violence against women, which is tolerated by state authorities; the deprivation of land and political participation of indigenous peoples and communities; discrimination against the Afro-Descendant population in access to education and justice; the bureaucratic abuse of undocumented immigrants; the massive displacement of the rural population in the context of social and political violence.

Thus, one of the main contributions and, at the same time, principal challenges of the ISHR regarding the regional problems rooted in institutional exclusion and degradation, lies in its capacity to set standards and principles to guide the actions of democratic States in specific situations, through the jurisprudence of the courts, to determine the scope of rights, as well as through the formulation of public policies, thereby contributing to the strengthening of institutional and social guarantees of these rights in different national spheres.

Faced with these types of situations, the Inter-American Commission and Court have sought to examine not only isolated cases or conflicts, but also the institutional and social contexts in which these cases and conflicts develop and gain meaning, similar to its role during the dictatorships and regimes of state terrorism, when the ISHR had monitored the situation of certain victims, the execution and forced disappearance of certain persons, a function of the context of massive and systematic violations of human rights. At present, in various situations, it has sought to frame particular facts in structural patterns of discrimination and violence against certain social groups or sectors. To do so, the ISHR has anchored itself to the principle of equality, which we will be summarily presented below. The reinterpretation of the principle of equality has allowed the ISHR to involve itself with social issues in light of a reinterpretation of the scope of civil and political rights established in the American Convention.

It important to illustrate the change of focus mentioned above and to discuss some ISHR interventions in cases concerning equality issues that are associated with various forms of violence, or matters relating to political participation and access to justice. These precedents constitute a line of jurisprudence that tends to a socially mindful reading of numerous civil rights in the American Convention, and affirms the existence of duties of positive action and not just the negative state obligations. These affirmative duties are generally exacted with greater intensity, as a result of the recognition that certain social sectors live in disadvantaged structural conditions in accessing or exercising their basic rights.

By observing the evolution of the jurisprudence on equality in the Inter-American system, one concludes that the ISHR demands of the states a more active and less neutral role, as a guarantee not only of the recognition of rights, but also of the real possibility of exercising them.

In this sense, the historical perspective on the jurisprudence of the ISHR shows the evolution of the concept of formal equality, developed during the transitional period, to a notion of substantive equality that has become more solid in the current phase characterized by the end of the transition to democratic regimes, when the subject of structural discrimination is presented with greater force in the cases considered by the ISHR. Thus, the idea evolves from its perspective of equality as non-discrimination, or as the protection of subordinates. This means that it evolves from a classical notion of equality, which focuses on the elimination of privileges or unreasonable or arbitrary differences, and which seeks to produce equal rules for all, and demands of the State a kind of neutrality or “blindness” with respect to differences And it moves towards a notion of substantive equality, which requires the state to assume an active role in attaining social equilibrium, granting special protection to certain groups who have suffered historical and structural discrimination. This notion requires the state to abandon its neutrality and rely on tools to diagnose the social situation to identify groups or sectors that should receive, in a given historical moment, urgent and special measures of protection.

In a report recently published by the Inter-American Commission, there is a systematization of the jurisprudence that shows the evolution of the concept of equality in relation to women’s rights (IACHR, 2007a).

There are some clear consequences of the adoption of the idea of structural equality by the Inter-American system. First, affirmative action by the state cannot be invalidated under a notion of formal equality. In any case, challenges to affirmative action must be based on concrete critiques of its reasonableness in light of the beneficiary group’s status in a given historical moment. The second consequence is that states not only have the obligation not not to discriminate, but also of adopting affirmative action measures in instances of structural inequality, to ensure that certain marginalized groups be able to fully exercise their rights. A third consequence is that the state can violate principles of equality with practices or policies that on their face value are neutral, but that have a discriminatory impact or effect on certain disadvantaged groups.

This has already been noted by the Court, in the case of Yean and Bosico against Dominican Republic (IACHR COURT, 2005d). A number of practices that on their face value might appear neutral or lack the deliberate intent to discriminate against a certain group could in fact have a discriminatory effect on that group, thus violating the rule of equality. These consequences are based on a social reading of the equality principle, since these state actions can go beyond affecting a sole individual and impact an underprivileged sector of the population. It is tantamount to changing the lens and opening the prism. One need only observe the social context and trajectories of certain individuals who are part of a group suffering discrimination. Therefore, not only will norms, practices and principles that deliberately exclude a given group, without a legitimate purpose, violate the principle of equality, but so will those that have a discriminatory impact or effect.8

At the same time, this concept of equality is reflected in the way the ISHR has started to reevaluate the obligations of states with respect to civil and political rights in certain social contexts.

Some important precedents on the extent of the state’s duty to protect, in relation to non-state actors can be highlighted, for example regarding violence against women. The IACHR imposed special obligations of state protection tied to the right to life and to physical integrity based on an interpretation of the principle of equality in line with what was discussed earlier. In the case of María da Penha Fernández against Brazil, the IACHR, against a structural pattern of domestic violence affecting the women of Fortaleza, Ceará state, where there was a general practice of judicially sanctioned impunity in these kinds of criminal cases, and the negligence of the local government in implementing effective prevention measures, established that the federal government had violated the victim’s right to physical integrity and equality under the law. It also established that the states have a duty to take diligent preventative action to deter violence against women, even with respect to non-state actors, based not only on Article 7 of the Convention of Belém do Pará but also on the American Convention. The State’s responsibility stemmed from not having adopted duly preventative measures. The IACHR fundamentally assesses whether there is a pattern or “systematic rule” in the State’s response, which expresses in its view a kind of public tolerance of the violence denounced, to the detriment not only of the individual victim but also of others similarly situated. The focus, as stated before, goes beyond the situation of one particular victim, and instead is on the discrimination and subordination faced by the particular social group. The structural situation of women victims of violence on the one hand describes the state’s duty to protect and provide reparations in a particular case, but also justifies the generalized recommendations made by the IACHR that include, for example, changes in public policy, legislation and judicial and administrative procedures (IACHR, Maria da Penha Maia Fernández vs. Brasil, 2001a, Campo Algodonero: Claudia Ivette González, Esmeralda Herrera Monreal y laura Berenice Ramos Monárrez vs. México, 2007c). The IACHR gave special attention to the more severe effects suffered by certain social groups as a result of violence inflicted by state or non-state agents with the acquiescence or tolerance of the State. In this vein, the Commission, for example, held Brazil liable for not having adopted measures to prevent violence due to forced evictions undertaken by private armies of landowners, an expression of systematic rural violence tolerated by state officials, followed by systematic impunity when criminal investigation of these incidents are conducted. In light of this, the IACHR especially took into account the situation of structural inequality amongst the rural population in certain states in the Brazilian northern region, where there is collusion between the powerful landowners, the police, and the state justice system (IACHR, Sebastião Camargo Filho vs. Brasil, 2009a). In another case, the IACHR held Brazil liable for systemic police violence directed at black youth in the shantytowns of Rio de Janeiro, considering that the extrajudicial execution of a young member of this social group, was representative of this pattern, which in turn reflects a racial bias in the state police’s conduct, with the complicity of the federal authorities (IACHR, Wallace de Almeida vs. Brasil, 2009b). Furthermore, the Inter-American Commission and Court consider this increased vulnerability that certain groups experienced in the context of the internal armed conflict in Colombia, imposing upon the state specific duties of protection that imply restrictions on the state’s use of force, and special protection against other non-state actors, as well as special reparation obligations to a given community and socially progressive and culturally relevant policies. These protections stem from the obligation to respect and guarantee given cultural rights of ethnic groups, such as restrictions on certain military activities in defense of the land of indigenous peoples and black communities in Colombia.9

Amongst the groups suffering discrimination that require special protection or treatment by the ISHR are indigenous peoples10 and the Afro-descendant population (FRY, 2002, ARIAS; YAMADA; TEJERINA, 2004)11 and women with respect to the exercise of certain rights, such as physical integrity12 and political participation.13 It has also emphasized the states’ obligation to protect vulnerable groups, such as children who live on the street or in detention centers, the mentally ill who have been institutionalized, undocumented immigrants, the rural population displaced from their land, and the poor infected with HIV/AIDS, amongst others.

This brief review shows that the ISHR does not merely use a formal notion of equality, which requires objectively reasonable laws and prohibits laws that favor or disfavor groups in an unreasonable, capricious or arbitrary manner, but rather moves towards a concept of material or structural equality that recognizes that certain sectors of the population are disadvantaged in exercising their rights, due to legal and factual obstacles and consequently require the adoption of special measures to guarantee equality. This implies the necessity of differential treatment, when due to circumstances affecting a disadvantaged group, when identical treatment involves restricting or cutting access to a service or good, or the exercise of a right. It also requires an examination of the social trajectory of the alleged victim, the social context in which the norms and policies are considered, and the degree of subordination of the social group in question.14

The use of the notion of material equality implies a definition of the state’s role as active guarantor of rights, in social contexts of inequality. It is also a useful tool to examine the legal framework, public policies and state practices, both their formulation and effects. The imposition of positive obligations has very important consequences for the political or promotional role of the ISHR, as it imposes on states the duty to formulate policies to prevent and redress human rights violations affecting certain disadvantaged groups or sectors.

It also has direct consequences on the debate about the availability of judicial remedies, as it is known that affirmative obligations are more difficult to impose on national justice systems, especially when positive behavior is required to resolve collective disputes.

Affirmative obligations are also in tension with the capabilities of American states. The ISHR has gradually imposed further obligations on the state to protect rights and deter violations with respect to non-state actors in particular circumstances. This expansion of state obligations highlights the gap between the expectations placed on atates and the states’ weak institutions and ineffective policies. To meet the exacting standards of the ISHR in regards to affirmative obligations, demands institutions that can formulate and implement policies and adequate human and financial resources. One can begin to see with greater clarity the growing gap between normative discourse and the actual capacity to meet the obligations imposed.

Affirmative obligations have also been imposed by the ISHR in relation to the right of participation of indigenous peoples. Amongst others, this includes the right to be consulted ahead of time about the policies that might affect their communal lands, such as the exploitation of economic and natural resources, and the right to dialogue with governmental bodies and other stakeholders through its own mechanisms of political representation (AYLWIN, 2004). This topic shows the direct link between the exercise of social and cultural rights and of civil and political rights, since the basis of the argument is the special ties that indigenous peoples have to their lands and natural resources, which not only puts at risk economic interests, but also the preservation of their cultural identity and the very perpetuation of their culture.15 These rights that are determined by international agreements, such as the ILO Convention 169, have also been recognized as being based directly on the American Convention, from a socially informed rereading of Article 21, which enshrined the right to property.

In a series of decisions the Inter-American Court has established the obligation of states to have adequate mechanisms for political participation, the production of information on social and environmental impacts, and consultation seeking consent of the indigenous peoples in decisions that affect the use of natural resources or alter its territorial boundaries. In this sense, it is a matter of recognizing the powers of diverse political participation in shaping the State’s public policies, but which at the same time goes beyond a procedural right and achieves the recognition of a “special group right” to preserve an area of self-government or autonomy in such matters (IACHR COURT, Comunidad Mayagna (Sumo) Awas Tingni, 2001, IACHR COURT, Masacre de Plan Sanchez vs. Guatemala, 2004a, Comunidad Moiwana vs. Suriname, 2005a, IACHR COURT, Comunidad Indígena Yakye Axa vs. Paraguay, 2005b, IACHR COURT, Pueblo Saramaka vs. Suriname, 2007). While the ISHR’s case law has established that it does not confer veto power upon indigenous peoples, this is undoubtedly one of the most contentious issues of those presently addressed by the ISHR, as one can more clearly see the tension between the recognition of a favorable group right, and certain economic development strategies of the states meant to promote the public interest.

In a recent decision issued by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, the obligation was imposed upon the states to adopt affirmative measures to ensure that the indigenous communities can participate, on equal footing, in making decisions on issues and policies that influence or could influence their rights in the development of those communities, so that they can integrate themselves into state institutions and organs and participate in a manner that is direct and in proportion to their populations in the management of public affairs, and do so through their own political institutions and in accordance with their values, customs, habits, and means of organization.

The Court, in its ruling in the Yatama case (IACHR COURT, Yatama vs. Nicaragua, 2005c),16 determined that the Nicaraguan law on the monopoly of political parties, and the decisions issued by the state’s electoral organs, had unreasonably limited the possibility of electoral participation by an organization representing indigenous communities from the country’s Atlantic coast. This case also expresses an affirmation of the principle of structural equality, as the Court requires the State to show flexibility in applying the electoral norms of general applicability so that they fit the mechanisms of political organization that express the cultural identity of a group. Ultimately, the Court recognizes a “special right conferred upon a group” (KYMLICKA, 1996, 1999), which gives the minority group certain “external protections” that are considered indispensable for the preservation of its autonomy, but also its participation in the State’s political structures.

The ISHR has also imposed strong affirmative obligations to ensure the right to have access to justice, which provides another layer of protection in the field of substantive equality. The ISHR has set specific standards about the right to have access to judicial and other kinds of remedies to sue for the violation of fundamental rights. In this regard, the state’s obligation is not merely negative, not to impede access to these remedies, but rather fundamentally positive, to organize the institutional apparatus in such a way that all, and especially the poor and the excluded, can obtain these remedies, thereby overcoming social and economic obstacles that render access to justice more difficult. Moreover, the State should organize a state legal aid office, as well as mechanisms to reduce the costs of litigation and make it affordable, for example, by implementing a system that waives costs.17 The policies that aim to ensure that the indigent receive legal services act as mechanisms that compensate for conditions of material inequality that affect the ability to effectively defend their own interests and, thus, are judicial policies that are related to social policies. The ISHR has established that the State has a duty to organize these services to compensate for conditions of inequality, and to ensure a level playing field in a judicial proceeding. It has also imposed certain concrete due process obligations relating to judicial proceedings involving social issues, such as judgments regarding labor and pensions rights and eviction cases. Recently, it established some indicators to assess whether the states are honoring these obligations. (IACHR, 2007a).18

This basis of positive obligations imposed on states, linked to the recognition of an assessment of inequality that characterizes the American reality, sometimes serves as a framework for examining public policy in the thematic and country reports, as was mentioned above, and is a central tool for the promotional work of the ISHR bodies.

The authority of the decisions and of the jurisprudence of the System depends in part on their social legitimacy and on the existence of a community of engaged actors who monitor and disseminate their decisions and standards. It does not exert its influence through coercive mechanisms, which it lacks, but through a power to persuade that it should build upon and preserve.

Thus, in countries in which international human rights law is part of daily legal discourse and arguments raised in the courts, there are some factors that should be highlighted. On the one hand, the ISHR has gained legitimacy through its association with the political processes of countries at key moments, especially the resistance to dictatorships and the reconstruction of the democratic and constitutional order. On the other, and in part because of this, there is a community of social, political and academic actors who consider themselves protagonists in the ISHR’s evolution and participate actively in the national implementation of its decisions and principles.

Many countries in Latin American ratified human rights treaties and joined the ISHR as they transitioned to a democratic regime, as a kind of antidote to reduce the risk of a return to authoritarianism, tying their legal and political systems to the “mast” of international protection.19 Subjecting human rights issues to international scrutiny was a functional decision made in furtherance of institutional consolidation during the transition period, as it served to fortify fundamental human rights protection in a political system hamstrung by military actors with veto powers, and still powerful authoritarian pressures.20

In Argentina, for example, support for human rights treaties takes place in 1984 at the beginning of the transition to democracy. The incorporation of human rights treaties into the constitutional hierarchy in 1994 was an important step in this process. Another important step was the Commission’s visit to the country in 1979 during the military dictatorship, and its report, which served to strengthen victims’ rights organizations and to weaken the government in the international community. In Peru, the legitimacy gained by the Commission and Court for denouncing human rights violations committed during the Fujimori administration has been critical. The IACHR’s visit to Peru in 1992, and later in 1999, and its report about “democracy and human rights,” together with the Court’s paradigmatic decisions on anti-terrorist legislation, freedom of expression and military commissions, helped document and expose the gravity of rights violations committed during this period. The full return of Peru to the ISHR in 2001 and the acceptance of responsibility, before the international community, for the atrocities committed during the Fujimori regime, were core policies of the transitional government. This has contributed to the formation of a group of social organizations, academics, judges and legal practitioners that are familiar with the system.

While in the last decade countries in the region have made considerable progress incorporating international human rights law into their national legal system, the Court’s jurisprudence is seen as a guide, even an “indispensable guide” for the interpretation of the American Convention by local judges,21 the process is not linear and there are dissident voices.

Recent decisions of appellate courts in the Dominican Republic and Venezuela have downplayed the forcefulness of the Court’s decisions and sought to give national courts the power to review its decisions (a legality test), to assess the compatibility of the international organ’s decision with the country’s constitution. This is an ongoing debate amongst the continent’s different judicial systems, where resistance to the incorporation of international human rights law in national legal systems still carries considerable weight, and many argue for greater national autonomy in this area.

The legal review of these decisions goes beyond the scope of this article. It is noteworthy, however, that, often, certain positions that criticize the growing limitation on the autonomy of states in addressing human rights issues often start with a simple vision or scheme to create international norms and apply them domestically. On the one hand, they downplay the importance of the participation of social actors and local institutions in creating norms and international human rights standards. On the other, they consider the domestic application of international norms as if it were an external imposition upon the national political and legal system, without considering that this incorporation is only possible through the active participation of relevant political, social and judicial actors, and by the gradual building of consensus in various institutional settings. Although there is typically a clear boundary between the international and domestic spheres, the boundaries are blurred when the dynamic of international mechanisms is examined. There is a constant back-and-forth between the local and international spheres, both in creation of human rights norms, and in their interpretation and application. Thus, relevant social actors and local politicians often participate in the process of the creation of norms in the international sphere, through both the ratification of treaties as well as decisions issued by international organs, which interpret their provisions and apply them in specific cases. At the same time, these international norms are incorporated into national legislation by the respective Congresses, governments and judicial systems, and also with the active participation of social organizations that promote, demand and coordinate the domestic application of international norms before various state organs. The application of international norms on the national level is not a mechanical act, but rather a process that involves different kinds of democratic participation and deliberation and provides ample room for a rereading or reinterpretation of the principles and international norms in accordance with each national context.22

In regard to the ISHR, as was shown in paragraphs 2 and 3 of this article, nowadays, in contrast with the periods of dictatorship, its intervention in certain domestic matters may reflect its working relationship with diverse local actors, both public and social, that participate in the formulation of demands on the international level, including how best to implement the ISHR’s standards and rulings internally.23 It is thus difficult to conceptualize its intervention as a simple limitation on the autonomy of national political processes. International intervention in this context is varied and complex, but generally has the support of strong local actors, who help apply international standards on the domestic level. For example, on occasion the ISHR has leaned on civil society to monitor government activity in the classical manner;24 it can also coordinate with the federal government to implement policies in the local states and provinces;25 occasionally it will rely on court decisions to develop guidelines that the Congress and Government can use for follow-up action;26 or the Governments or the Congresses ask for its intervention to help build consensus amongst the other governmental branches, such as the Judiciary,27 or to monitor the resistance of local social and political actors regarding the implementation of measures.28 Often local courts cite ISHR decisions to monitor governmental and congressional policies.29 We also saw that in certain cases, and in particular in “friendly settlement” negotiations, the texture of alliances is even more complex, as even public agencies petition the ISHR, sometimes in partnership with social organizations, looking to trigger international scrutiny of particular questions. With this brief review, one does not intend to deny the importance of preserving the political autonomy of the states to address certain issues, but rather to put into perspective certain interpretative approaches about how an international justice system actually works and how it relates to national political processes.

An important factor in increasing the application of international law by national justice systems is the presence of a strong academic community that critically discusses the international system’s decisions and provides input as to how judges and legal practitioners can make use of this jurisprudence. This local and regional academic community is not only indispensable in ensuring the application of Inter-American standards at the domestic level, but also to hold the ISHR organs themselves accountable and exert pressure for an improvement in the quality, consistence and technical rigor of their decisions. While recently there have been clear signs of progress, it is still not possible to verify the existence of this community at the regional level. There is little discussion and critique of the decisions of the Court and Commission, and these decisions are hardly known in several countries. The underwhelming debates that have taken place recently have resulted in a reassessment, at least on a theoretical level, of some premises. As an example, it is interesting to consider issues rooted in traditional criminal doctrine and relevant to the criminal prosecution of gross human rights violations established in the ISHR’s jurisprudence and its impact on the rights of the accused, such as the principle of res judicata and ne vis in idem (MARGARELL; FILIPPINI, 2006), as well as discussions in constitutional theory about the value of the decisions issued by international human rights organs. The democratic deficiencies of these international organs, or their lack of knowledge about what goes on inside national political communities, are questioned (GARGARELLA, 2008).30

It is true that the level of compliance of particular decisions issued by the ISHR is important vis-à-vis reparation measures, as well as on measures of legislative reform, mentioned above. In both cases, some preliminary studies suggest that the highest level of compliance is found in the context of friendly settlements, where the state has the autonomy to determine how it will meet the terms of the agreement.

The main problems, however, regarding non-compliance with the IACHR’s recommendations and the Court’s judgments, relates to criminal investigations conducted by the state, particularly when they have closed the investigation and its reopening could affect the rights of the accused. In some countries, courts have significantly deteriorated while participating in a culture of widespread impunity, which is not limited to cases involving human rights violations. The ISHR has used its review of structural patterns of impunity to invalidate judicial decisions that attempt to close the investigation of such crimes, usually to benefit groups in power, to the detriment of a certain class of victims.31

There have been no significant advances in how states’ internal mechanisms implement decisions issued by the ISHR’s organs.32 This in particular becomes an obstacle when dealing with the impositions of affirmative obligations. Complying with the reparation measures issued by an international organ requires a high level of coordination between governmental agencies, which is often not achieved. This significantly hampers the processing of the case, the work of the ISHR’s organs, and the enforcement of decisions. Effectively coordinating between agencies even within the same government is complex, and even more so when the government must coordinate its activities with Parliament of the judicial system, when the measures involved in a case require legal reforms or the filing of lawsuits. This issue is even more problematic when agencies from the federal government must coordinate their activities with state governments in a federalized system.

The Inter-American Commission and Court drafted a report for the General Assembly of the OAS about non-compliance with their decisions, but they are given minimal time to present information on the states’ mechanisms of implementation. Moreover, there is no serious debate within the system on how to improve enforcement mechanisms of a political nature and attain greater commitment by the various organs of the OAS.

The most effective enforcement mechanism has been the creation of institutions of international supervision, such as follow-up hearings before the Commission or Court. Many victims’ rights organizations prefer these international supervisory mechanisms to internal enforcement systems, since they realize that attempting to compensate the victims at the national level will be disadvantageous for them, in light of the state’s excessive power. Only the involvement of an international organ can level the playing field (ABREGÚ; ESPINOZA, 2006).

Another point to consider when examining obstacles reducing the system’s effectiveness is the kind of remedy available, such as reparation measures in contentious cases, such as provisional or cautionary measures. Often, the remedies proposed result from suggestions made by the petitioners and victims’ representatives, and there is no line of case law about this. Furthermore, the remedies are designed in accordance with a model developed during the transitional period, emphasizing the thoroughness of the investigation and determination of those responsible for the violations, and placing less emphasis on the structural problems the violations represent. The system of traditional remedies does not fully fit with the type of conflict found in the new agenda we referred to earlier, above all, when the ISHR does not limit itself to judging past events, but seeks to prevent harm and the aggravation of precarious situations, and aims to bring about the reversal of systematic patterns or overcome institutional deficiencies. This was explained more clearly in the context of the Court’s interim measures in connection with prison reform. These issues involving inhumane detention conditions and structural patterns of violence tolerated by the state and federal authorities, functions as a kind of collective, international “habeas corpus” petition. They have developed an interesting debate about the kind of remedies and local and international mechanisms of supervision. The Court, at the request of the petitioners and the Commission, has gradually modified the kind of remedies imposed on the federal government and state governments, but it still has not achieved adequate compliance with its orders. The logic behind the remedies is similar to the remedies granted in the context of structural reform litigation in national courts. In this kind of case, it is necessary to balance several competing interests and give the government room to adopt measures, introducing medium term and long-term plans of action. It also seeks to protect the right to access information, and the right of victims and their representatives to participate in shaping these policies (SABEL; SIMON, 2004, GAURI; BRINKS, 2008, ABRAMOVICH, 2009). It is still open to discussion whether these kinds of international supervision measures can be effective, without involving the national judicial l system and national public organs that monitor and evaluate the situation inside the penitentiary system.33

The persistence of low levels of effectiveness of these types of structural remedies can lead to a rethinking of all facets of the ISHR, and erode the Court’s legitimacy. The ISHR has begun to develop a model of structural litigation to protect groups, without having refined it or engaged in an in-depth discussion about the limits and potentialities of its procedural rules34, its system of remedies, and its mechanisms for the supervision of its decisions.

The debate about the effectiveness of international supervision is tied directly to a question that is critical to democratic processes, which is the poor performance of local judicial systems.

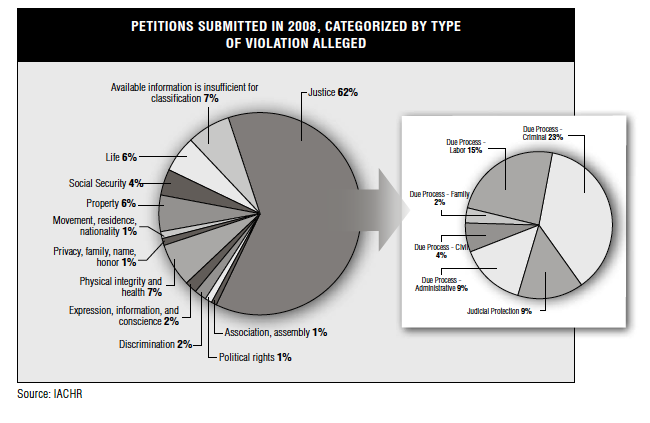

The chart below shows a division by topic of petitions received by the IACHR in 2008. The problems associated with the functioning of national judicial systems were the central focus, as 62% of the complaints filed are on this topic. A further breakdown of the “justice” complaints reveals that 23% dealt with due process, 15% with labor law, and 9% with administrative procedure.

Without a doubt, the response of national justice systems is critical to improving the effectiveness of the ISHR. It has taken important steps on this path by setting clear principles on what constitutes independent and impartial courts, a reasonable length of trial, the exceptional use of precautionary imprisonment, the reach of res judicata, and judicial review of administrative decisions, amongst others. A better systematization of this case law can serve as the guiding framework for judicial reform policies in the region, improving the enforcement of rights in local judicial systems. The monitoring of national judicial systems is a priority on the IACHR’s agenda, which can be concluded from the themes of its recent reports and documents.

The development of affirmative obligations in the field of human rights, as well as of rights that may have a collective dimension, requires determining with greater precision what constitutes adequate and effective remedies in furtherance of their protection. An adequate and accessible system of collective actions, such as collective protection, writs of mandamus, class action suits, and emergency precautionary protective measures, can promote local litigation in the public interest that allows national courts to rule on many cases heard in the international arena. The promotion of judicial remedies for local public interest litigation, in the field of human rights, is therefore also a strategy the ISHR should pursue.

Undoubtedly, the ISHR has significant legitimacy, which originated in its efforts to destabilize the dictatorships, and continued as it monitored the process of transition to democracy. In this article, it was suggested that in the present political landscape in Latin America, the strategic value of the ISHR consists in strengthening democratic institutions, especially judicial systems, and national efforts to overcome current levels of exclusion and inequality. In light of this, in addition to the efficacy of its jurisprudence and the development of its system of individual petitions, the ISHR should reflect on its political role, setting its sights on the structural patterns that impact the effective exercise of rights by disadvantaged sectors of the population. To achieve this, it should safeguard its subsidiary role to the national justice systems and ensure that its principles and standards are incorporating not only the reasoning of domestic courts, but the general trend of the laws and governmental policies.

1. The Court invalidated the provisions of Chilean self-amnesty in (Inter-American Court of Human Rights, Almonacid Arellano et al vs. Chile, 2006b). Without citing this precedent, arguments can be found in international humanitarian law and international human rights law that are grounded in the judgments of the Chilean Supreme Court, which struck down this norm (CHILE, Events that occurred in the Cerro Chena regiment, 2007).

2. In these decisions, the Court develops a basic doctrine about the relationship between human rights, procedural due process, the rule of law and democratic systems, with representational bodies reflecting the popular will.

3. See the doctrine explained by the IACHR in its most recent reports about inadmissibility, which includes declining to review criminal convictions that are allegedly unfair, given the impossibility of substituting its judgment for that of the national courts in the assessment of evidence (IACHR, Luis de Jesus Maldonado vs Manzanilla. Mexico, 2007d). Of course the line between reviewing court judgments or evaluating evidence of reasonableness, and observing certain procedural safeguards established by the Convention, is sometimes blurry, and requires fine-tuning technical standards.

4. See the debate about positive state obligations in electoral matters, and the deference granted to design electoral systems and political parties (IACHR, Jorge Castañeda Gutman vs. México, 2006, 2008c; IACHR COURT, 2008).

5. See, for example, a report about the human rights situation in a country that reflects the agenda of social exclusion and the perspective of impact on public policies: (IACHR, 2003, 2007d).

6. Regarding the value of these thematic reports, as an impactful tool at the IACHR in the context of the region’s deficient democracies, see the precise analysis of (FARER, 1998). For an example of this type of thematic report, see (IACHR, 2006a). For an example of a thematic report applied in the domestic context, see (IACHR, 2006b, 2009a, 2009b).

7. See (IACHR, Nicaragua vs. Costa Rice, 2007). In June 2009, Ecuador’s Attorney General filed a petition against Colombia with the Executive Secretary of the IACHR, alleging violations of the American Convention for the death of Franklin Aisalia, the result of a Colombia military operation in March 2008 against a FARC encampment in Angostura, Ecuador.

8. Along these lines, the Court held in the case Niñas Yean y Bosico vs. República Dominicana (IACHR COURT, 2005d): “The Court considers that the binding legal principle of equal and effective protection of the law and non-discrimination mandates that the States, in regulating the mechanisms of granting citizenship, should abstain from promulgating regulations that discriminate on their face or in effect against certain sectors of the population when exercising their rights. Moreover, States must combat discriminatory practices at all levels, especially in government, and ultimately must adopt the necessary affirmative measures to ensure effective equality under the law for all persons.”

9. The Court’s interim measures are available, in the case of the indigenous people Kankuamo (Inter-American Court, 2009a), and in the case of the Afro-Colombian communities of Jiguamiandó and Curbaradó (Inter-American Court, 2009c), amongst many others. See also the situations mentioned in the context of the Colombian armed conflict (IACHR, 2008d).

10. Regarding the States’ affirmative obligations to guarantee the exercise of certain civil, political and social rights of members of the indigenous communities, see the following cases: Masacre de Plan Sanchez vs. Guatemala (Inter-American Court, 2004a); Comunidad Moiwana vs. Surinam (Inter-American Court, 2005a); and Comunidad Indígena Yakye Axa vs. Paraguay (Inter-American Court, 2005b). Recently, this principle led the Court to reinterpret the State’s obligation regarding the right to life to include a duty to ensure a minimum level of health, water and education, tied to the right to a life of dignity of an indigenous community expelled from its lands, in the case Sawhoyamaxa vs Paraguay (Inter-American Court, 2006a) and subsequent decisions monitoring the execution of the sentence.

11. See the case Simone André Diniz v. Brazil (Inter-American Commission, 2002), declared admissible by the Inter-American Commission for the state’s breach of a duty to protect individuals from discrimination based on color or race.

12. Regarding the obligation to adopt affirmative policies and measures to prevent, punish, and eradicate violence against women, see (Inter-American Commission, Maria da Penha Maia Fernández vs. Brasil, 2001a).

13. Regarding quotas in the Argentine electoral system, (Inter-American Commission, 2001b).

14. For a discussion of these notions of equality in legal philosophy and constitutional law, see the following examples (YOUNG, 1996, FERRAJOLI, 1999, GARCIA AÑON, 1997, FISS, 1999, GARGARELLA, 2008, SABA, 2004).

15. Regarding collective rights for the preservation of a culture and the neutrality of the liberal state, see the classic essay by Charles Taylor (1992) and Anaya (2005).

16. In this decision, the Court began to define the scope of the right to political participation enshrined in Article 23 of the American Convention and asserts that it includes participation in formal electoral processes as well as participation in other mechanisms for discussion and monitoring of public policies. In its sentence the Court also states with greater precision the scope of the State’s obligation to ensure such participation in socially disadvantaged groups that are trying to exercise this right. The Court links this right to both formal and substantive equality, which includes the right to association and political participation. On this topic, see the concurrence of Judge Diego García Sayan. To better understand the Court’s reasoning in Yatama, it is helpful to read a subsequent, contrasting case about the exclusion of independent candidates, especially considering in Yatama the existence of a subordinate group with its own specific cultural characteristics (Inter-American Court, Jorge Castañeda Gutman vs. México, 2008).