The South African Police Service and the ‘War’ on Violent Crime

In the context of high levels of firearm violence in South Africa this article assesses the attempts by the police to leverage effectual control over the proliferation and misuse of firearms. A key strategy has been that of militarised high density policing operations in the context of a ‘war on crime’ ideology. Through roadblocks and cordon-and-search interventions police have seized very large quantities of firearms and ammunition from high crime areas, and arrested thousands of individuals for a range of crimes, including being in possession of unlicensed firearms. Declining trends in firearm homicide between 1998 and 2011 possibly suggest that these South African Police Service (SAPS) operational efforts may have contributed to reductions in firearm homicide. However, such operations have led to the police being exceedingly invasive and employing heavy-handed methods. Some individuals have also been injured, or have lost their lives as a result of these police operations.

South Africa is one of the most violent countries in the world. It had the ninth highest recorded homicide rate in 2012, with 31 homicides per 100,000 people, which was five times the global average.11. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Global Study on Homicide 2013. Trends, Context, Data (Vienna: UNODC, 2014). Between 1 January 1994 and 31 March 2014 an estimated 143,000 people were murdered with a firearm, which is equivalent to 35% of all murders for that period.22. Western Cape Government, Department of Community Safety, The Effect of Firearm Legislation on Crime: Western Cape (Cape Town: Western Cape Provincial Government, 2015); Robert Chetty, “The role of firearms in crime in South Africa,” in Firearm use and distribution in South Africa, ed. Robert Chetty (Pretoria: National Crime Prevention Centre, 2000), 16-29. In addition, an estimated 1.25 million people in South Africa seek medical assistance for non-fatal violence-related injuries every year, with a significant number of firearm related injuries being presented.33. Mohamed Seedat et al., “Violence and Injuries in South Africa: Prioritising an Agenda for Prevention,” The Lancet 374, no. 9694, (2009): 1011–1022.

South Africa has a relatively large and well-armed police force, with close to 200,000 personnel employed by the South African Police Service (SAPS), rendering a 1:358 police to population ratio. The majority of operational police are issued with handguns, with the police reporting that they have 259,494 firearms in their possession.44. South African Police Service, South African Police Service Annual Report 2014/15 (Pretoria: South African Police Service, 2015). Furthermore, the SAPS has specialised paramilitary operational response bodies equipped with high-calibre weapons that can be swiftly deployed in incidents of public disorder, violent crime and terrorism.

Over the past twenty years a key response by the SAPS to these high levels of violence, particularly firearm crime, has been to launch large-scale, militarised, crackdown (or high density) operations in areas where there are excessively high levels of reported violent crime. The principal rationale behind the adoption of this approach has been that by concentrating police resources on crime hotspots the government “hoped that the national level of serious crime [would] be reduced”.55. Steve Tshwete, “South Africa: Crime and Policing in Transition,” in Crime and Policing in Transitional Societies, ed. Mark Shaw (Johannesburg: Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, 2000), 28. The ethos and approach of these operations has been drawn from colonial and apartheid policing traditions in South Africa, and have been informed by a belligerent “war on crime” philosophy.

This article provides an analysis of the war on crime approach to policing in post-apartheid South Africa, with a particular focus on high density policing operations. Furthermore, it will reflect on the impact of such operations on South African society, in particular their relationship with firearm homicide.

For the past two decades the SAPS crime statistics have consistently revealed the highly uneven distribution of violent crime throughout South Africa. Overall crime has manifested within most policing precincts, but violent crime has been intensely concentrated in around 15% of policing precincts. Most of the high crime places are densely populated and infrastructurally marginalised with high levels of poverty, such as large urban townships and informal settlements. In many of these places government authority has been undermined by limited community trust in the police.

Given these dynamics, the SAPS 1996/97 Annual Plan indicated that future policing efforts would be directed towards those provinces with the greatest intensities of violent crime, and that “all provinces would thus benefit” from this approach.66. South African Police Service, Annual Plan of the South African Police Service 1996/1997 (Pretoria: South African Police Service, 1996), 10. By 2001 SAPS had resolved that 145 police station precincts with “high contact crimes” would be prioritised in terms of receiving additional policing resources, and to be targeted for high-density operations.77. South African Police Service, Annual Report of the National Commissioner of the South African Police Service 1 April 2002 to 31 March 2003 (Pretoria: South African Police Service, 2003). The number of high contact crime police stations was subsequently increased to 169, which was emphasised in the SAPS 2005-2010 Strategic Plan.

In 1996 the National Crime Prevention Strategy (NCPS) was launched, the culmination of inputs and discussions by academics and government officials that was informed by development-centred crime reduction efforts in other countries.88. Gareth Newham, A Decade of Crime Prevention in South Africa: From a National Strategy to a Local Challenge (Johannesburg: Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation, 2005). This was an optimistic attempt by national government to fundamentally re-condition the police’s traditional response to crime from the repressive and reactive to the preventive and proactive. The implementation of the NCPS was envisaged to be an extensive, integrated, multi-layered, interdepartmental and public-private partnership enterprise.99. Janine Rauch, Thinking Big: The National Urban Renewal Programme and Crime Prevention in South Africa's Metropolitan Cities (Johannesburg: Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation, 2002). The SAPS’ response to such a radical policy shift on policing at this time was superficial and perfunctory.

In 1999 the security cluster of Cabinet Ministers, led by Steve Tshwete (Minister of Safety and Security) which had initially supported a social crime prevention orientation began to back the “get tough on crime” approach in the face of escalating violent criminality.1010. Elrena Van der Spuy, “Crime and its Discontent: Recent South African Responses and Policies,” in Crime and Policing in Transitional Societies, ed. Mark Shaw (Johannesburg: Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, 2000), 167–76. This was accompanied by widespread perceptions that the police were on the back foot in terms of containing crime. In addition, various government structures were struggling to prioritise and adapt to the multiple demands of a preventive strategy.1111. Rauch, Thinking Big; Cheryl Frank, “Social crime prevention in SA: a critical overview: what have we learned?” SA Crime Quarterly no. 6 (2003): 21–26; Johan Burger, Strategic perspectives on crime and policing in South Africa (Pretoria: Van Schaik, 2007). Within a short space of time the NCPS became marginalised, and the Safety and Security Secretariat, the NCPS champion, was downgraded to relative insignificance.1212. Paul Thulare, “Diminution of civilian oversight raises troubling issues,” Centre for policy studies, Synopsis, 2002. The NCPS was subsequently supplanted by the SAPS’ own National Crime Combatting Strategy (NCCS), which was launched in 2000, with the tacit endorsement of Cabinet.1313. Interview with Johan Burger, former SAPS Assistant National Commissioner (responsible for national policy and strategy) at the Institute for Security Studies offices, Pretoria, 18 November. 2015.

The NCCS emphasised an intelligence-driven, “high-density”, hotspot policing in which high crime areas, or “flashpoints” would be clustered into “crime-combating zones”.1414. Rauch, Thinking Big; Bilkis Omar, “Enforcement or development? Positioning government’s National Crime Prevention Strategy,” Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention, Issue Paper 9, July 2010. The NCCS effectively framed the strategic orientation of SAPS squarely within a militarised crime-fighting paradigm, where violent crime was to be eliminated through aggressive policing, and by capturing and imprisoning criminals. “War rooms” were established with a view to deliver a more effective, integrated and coordinated crime-fighting response.1515. Remarks by the Minister of Police, EN Mthethwa, MP at the American Chamber of Commerce in South Africa Dinner on “A Focus on the Future Plans of the South African Police Service, in the Short Term and Medium Term,” The Castle Kyalami, Gauteng, November 24, 2010.

The NCCS also became the foundation on which the police’s political leadership has perpetuated a “war on crime” discourse, frequently referring to criminals as the “enemy”,1616. Address by the Minister of Police, at the 2012 National Launch of the Operation Duty Calls Festive Season Crime-Fighting Campaign, Jane Furse Stadium, Sekhukhune District, Limpopo, September 12, 2012.reiterating that “collectively, we shall defeat this scourge”.1717. Murugan, S. and SAnews, “South Africa turning the tide against crime,” Vukuzenzele, October, 2012. In the 2011/12 SAPS Annual Performance Plan, for instance, the Minister of Police at the time, Nathi Mthethwa asserted that “military expertise” amongst criminals has “drastically changed the nature of crime”.1818. South African Police Service, Annual Performance Plan 2011/2012 (Pretoria: South African Police Service, 2011). Hence the police have been encouraged to: “shoot to kill”; “fight fire with fire”; “show no mercy” towards dangerous offenders; and “squeeze crime to zero”.1919. Andrew Faull and Brian Rose, “Professionalism and the South African Police Service. What is it and how can it help build safer communities?” Institute for Security Studies Papers no. 240 (2012): 24; Tony R. Samara, “Policing Development: Urban Renewal as Neo-liberal Security Strategy,” Urban Studies 47, no. 1, (2010): 197–214. For example, in April 2008, Susan Shabangu, the then Deputy Minister of Safety and Security proclaimed at a community meeting in Pretoria West:

Criminals are hell-bent on undermining the law and they must now be dealt with. If criminals dare to threaten the police or the livelihood or lives of innocent men, women and children, they must be killed. End of story. There are to be no negotiations with criminals. 2020. Graeme Hosken, “Kill the bastards, minister tells police,” IOL News, April 10, 2008.

On 16 August 2012 the National Development Plan (NDP) 2030, which has been identified by President Zuma as South Africa’s fundamental policy guidance, was published. It calls for the demilitarisation of the SAPS, and that all police personnel should be trained in “professional police ethics and practice”.2121. National Planning Commission, National Development Plan 2030. Our Future – Make it Work (Pretoria: The Presidency, 2012). However, the following day various components of the SAPS pursued a highly militarised operation in response to a mineworker strike in Marikana. This operation resulted in the massacre of 34 individuals with a further 78 being injured.

Over the past three years the Police Minister and SAPS senior management have made public pledges to the demilitarise and further professionalise the SAPS, with the NDP commitments being included in the SAPS 2014-19 Strategic Plan, as well as an indication that SAPS would pursue a new policy on public order policing that “provides direction for a human rights based approach to dealing with public disorder”.2222. South African Police Service, Strategic Plan 2014-2019 (Pretoria: South African Police Service, 2015). In addition, the Civilian Secretariat for Police has recently finalised a Draft White Paper on the Police and a Draft White Paper on Safety and Security, which encourages the SAPS to demilitarise and recommit to human rights principals. However, as with the NCPS, civilian policing specialists have mostly penned these documents, and hence there is a risk that they may not find meaningful traction with the SAPS.

Recent large-scale policing actions suggest that the SAPS may not be ripe for reform. In April 2015 the SAPS, in collaboration with the military, launched a highly militarised national operational titled Fiela-Reclaim following an outbreak of xenophobic violence (see below for more details). In November 2015 the SAPS used heavy-handed measures to disrupt nationwide protests by university students, primarily over fee increases. In addition, the “war on crime” is being perpetuated by the political leadership of the police. For example, at the memorial of murdered SAPS officials in Gauteng in August 2015, the Deputy Minister of Police, Maggie Sotyu declared that:

Our [SAPS] strategic implementation plan must always intend to treat heinous criminals as outcasts, who must neither have place in the society nor peace in their cells! They must be treated as cockroaches! 2323. Sotyu, M.M. Keynote Remarks of Support by the Deputy Minister of Police at the Joint Memorial Service of the Late Constables Buthelezi, Seolwane and Hlabisa, August 4, 2015.

Firearms have consistently been a top priority for the SAPS since the mid-1990s, and firearms control is currently emphasised in the SAPS 2014-19 Strategic Plan. A Firearm Strategy was devised in the late-1990s, which amongst other objectives, sought to: reduce the number of firearms within South Africa; “protect South African citizens from crimes associated with both illegal and legal firearms”; and give SAPS appropriate powers to investigate, confiscate and makes arrests in relation to firearm crime.2424. South African Police Services, Policy for the Control of Firearms in South Africa (Pretoria: South African Police Service, 2000). Therefore firearms control became a key emphasis of SAPS high-density operations.

The Firearms Control Act (FCA) (No. 60 of 2000) was subsequently formulated, and eventually became fully operational in 2004 with the promulgation of its requisite regulations. The FCA included the introduction of more rigorous firearm licencing requirements, such as: extensive background checks of applicants; an increase in the legal minimum age to possess a firearm to 21 years; a reduction in the number of licensed firearms and rounds of ammunition that an individual may possess; and the requirement that firearms be stored in secure safes. Penalties for licensing infringements and firearm misuse also became more stringent. In addition, all licence applicants were required to successfully complete a written test relating to firearm legislation, as well as undergo prescribed training and pass a practical test on the safe handling of a firearm with an accredited service provider.2525. Republic of South Africa, Firearms Control Act, 2000 (Act 60 of 2000) (Cape Town: Government Printer, 2001).

Furthermore, Chapter 14 of the FCA authorises the SAPS to enter any premises “on reasonable grounds” and search for, and seize firearms and ammunition from persons that they perceive to be “incapable of having proper control” of those firearms or ammunition, or who “presents a danger of harm to himself or herself or to any other person”. During the course of police operations SAPS are also permitted to search premises, vehicles, vessels and aircraft and seize firearms where there is “reasonable suspicion” that the firearms and ammunition are being held in contravention of the FCA; or to ascertain if the possession of the firearms and ammunition are in compliance with the Act.

High-density crackdown operations, or crime “sweeps”, typically entail a sudden and noticeable increase in the number of police personnel and concentrated police actions in targeted areas.2626. Michael S. Scott, The benefits and consequences of police crackdowns. Response Guide no. 1 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, 2004). They are based on the expectation that criminal offending will feasibly drop in circumstances where the likelihood of being detained is significantly elevated and/or where repeat offenders are targeted and arrested.2727. Jacqueline Cohen and Jens Ludwig, Policing Crime Guns, in Evaluating Gun Policy: Effects on Crime and Gun Violence, ed. Jens Ludwig and Philip J. Cook (Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution, 2003), 217–239; Steven Chermak, Edmund F. McGarrell and Alexander Weiss, “Citizens' perceptions of aggressive traffic enforcement strategies,” Justice Quarterly, 18 (2001): 365–391; Anthony A. Braga et al., Problem-oriented policing in violent crime places: A randomized controlled experiment. Criminology 37, no. 3 (1999): 541–580. Crackdowns are also expedient mechanisms to alleviate public criticism and blood baying about crime levels, as they “offer the promise of firm, immediate action and quick, decisive results”.2828. Scott, The benefits.

Available academic research from the United States and the United Kingdom suggests that such policing approaches can have a reduction impact on criminal offending in the focal areas, and possibly even in the surrounding areas in the short- to medium-term.2929. Anthony A. Braga, “The Effects of Hot Spots Policing on Crime,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 578, no. 1 (2001): 104–125; Gary W. Cordner, “Evaluating Tactical Patrol,” in Quantifying Quality in Policing, ed. Larry T. Hoover (Washington, D.C.: Police Executive Research Forum, 1996), 185–206; T.J. Caeti, Houston's Targeted Beat Program: A Quasi-experimental Test of Police Patrol Strategies (Ann Arbor: University Microfilms International, 1999); Anthony A. Braga and David L. Weisburd, Policing Problem Places. Crime Hot Spots and Effective Prevention. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010; Lawrence W. Sherman et al., “An Integrated Theory of Hot Spots Patrol Strategy: Implementing Prevention by Scaling Up and Feeding Back,” Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 30, no. 2 (2014): 95–122. Further to this, evidence suggests that crackdown operations should be publicised in advance,3030. Lawrence W. Sherman, “Police Crackdowns: Initial and Residual Deterrence,” in Crime and Justice: A Review of Research, ed. Michael Tonry and Norval Morris, vol. 12 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990), 1–48. and be “sufficiently long and strong” in order to have a more meaningful impact on crime levels.3131. Scott, The benefits. However, the research also indicates that if the police are overly aggressive and do not actively communicate their intentions during crackdown operations then police credibility and police relations with targeted communities and the general public can be severely undermined.3232. Lisa Maher and David Dixon, “Policing and Public Health: Law Enforcement and Harm Minimization in a Street-level Drug Market,” British Journal of Criminology 39, no. 4(1999): 488–512; John E. Eck and Edward Maguire, Have Changes in Policing Reduced Violent Crime? An Assessment of the Evidence, in The Crime Drop in America, ed. Alfred Blumstein and Joel Wallman (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 207–65; Lawrence W. Sherman, “Policing for Crime Prevention,” in Preventing Crime: What Works, What Doesn't, What's Promising: Report to the United States Congress, ed. Lawrence W. Sherman et al. (Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, 1997); David Weisburd and Cody W. Telep, “Hot Spots Policing: What We Know and What We Need to Know,” Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 30, no. 2 (2014): 200–20.

The SAPS defines high density policing as the “saturation of high crime areas with patrolling police members, performing pro-active patrols…[that are] intent on law enforcement”.3333. South African Police Service, Policing Priorities and Objectives for 1998/99 (Pretoria: South African Police Service, 1998), 41. High density policing was embedded in the NCCS,3434. South African Police Service, Annual Report of the National Commissioner of the South African Police 1 April 2001 to 31 March 2002 (Pretoria: South African Police Service, 2002), 6. and thereafter rapidly became the flagship policing approach for crime hotspots, eclipsing alternative crime prevention models, such as community policing. In essence, these SAPS dragnets have been grandiose meldings of the binary conceptualisation of high and low policing as advocated by Brodeur.3535. Jean Paul Brodeur, “High Policing and Low Policing: Remarks About the Policing of Political Activities,” Social Problems 30, no. 5(1983): 507–20. That is rank-and-file police personnel that are generally responsible for day-to-day order maintenance, as well as detectives, are deployed alongside specialised, paramilitary police groupings, such as the Public Order Policing Units, Dog Units and the Special Task Force.

The SAPS has consistently donned a militarised ethos in the design and execution of such operations. SAPS members have frequently been heavily armed and deployed in battle-ready formations and often supported by police and military armoured personnel carriers. The police have frequently entered and occupied the targeted areas like an invading army, usually in conjunction with contingents of South African National Defence Force (SANDF) soldiers. Many of these operations have been branded with martial titles, such as Operation Sword and Shield, Operation Crackdown, Operation Iron Fist, and most recently Operation Fiela3636. Fiela is a Sesotho term meaning “to sweep away; to clean up; to remove dirt”.-Reclaim.

In the context of these operations large numbers of security personnel have vigilantly patrolled the streets. Roadblocks have been erected. Residents, vehicles and premises have been searched, and at times doors to homes have been rammed open. Illegal firearms and ammunition, drugs, and stolen goods, including vehicles, have been seized. Those in possession of such goods have been arrested and hauled off to police cells, along those individuals “wanted” by the SAPS for serious crimes, as well as prostitutes, pimps and undocumented immigrants. Resistance or antagonism towards the security forces has usually been met with a hyper-belligerent response.3737. Jonny Steinberg, “Policing, State Power, and the Transition from Apartheid to Democracy: A New Perspective,” African Affairs, 113, no. 451 (2014): 173–91; Richard Poplak, “The Army vs. Thembelihle: Where the Truth Lies,” Daily Maverick, May 5, 2015; Tony Roshan Samara, “State security in transition: The war on crime in post apartheid South Africa,” Social Identities 9, no. 2 (2003): 277–312. SAPS high density operations have also drawn heavily from counter-insurgency doctrine, tactics and terminology in at least five respects.

Firstly, national operations have been centrally planned and directed, predominantly by the SAPS National Joint Operational and Intelligence Structure (NATJOINTS), which is responsible for coordinating all security and law enforcement operations throughout South Africa. The National Joint Operational Centre (NATJOC) has been responsible for driving the implementation of the operational strategies and instructions that have been determined by the NATJOINTS. Provincial structures, PROVJOINTs and PROVJOCs, have also been established to drive and coordinate operations at the provincial level.

Secondly, “cordon-and-search” has been a mainstay method used in SAPS high density operations, and entails the sealing-off of targeted areas in which houses and premises are searched in order to capture wanted persons and seize illegal weapons and other contraband. Cordon-and-search was originally pursued by colonial armed forces in order to pacify recalcitrant communities and capture suspected insurgents in Africa, South-East Asia and Northern Ireland.3838. David Kilcullen, Globalisation and the Development of Indonesian Counterinsurgency Tactics,” Small Wars and Insurgencies, 17, no. 1 (2006): 44–64; Monica Toft and Yuri M. Zhukov, Denial and punishment in the North Caucasus: Evaluating the effectiveness of coercive counter-insurgency,” Journal of Peace Research 49, no. 6 (2012): 785–800; David French, “Nasty not nice: British counter-insurgency doctrine and practice, 1945-1967” Small Wars & Insurgencies 23, nos. 4-5 (2012): 744–761. The South African Police also frequently employed such tactics under apartheid.3939. Gavin Cawthra, Policing in South Africa. The SAP and the Transformation from Apartheid. London: Zed Books, 1993.

Thirdly, air support (particularly helicopters) has been incorporated into SAPS operations. Air support has regularly been used in counterinsurgency campaigns to protect ground forces and provide surveillance.4040. Ivan Arreguin-Toft, “How the Weak Win Wars: A Theory of Asymmetric Conflict,” International Security 26, no. 1 (2001): 93–128; Nathaniel Fick and John A. Nagl, “Counterinsurgency Field Manual: Afghanistan Edition,” Foreign Policy, 170 (2009): 42–7. In extreme cases aerial bombardment takes place, a tactic that SAPS has not used to date.

Fourthly, the counterinsurgency concept of “flood and flush”4141. Daniel L. Byman, “Friends like these: Counterinsurgency and the war on terrorism,” International Security 31, no. 2 (2006): 79–115; John Mackinlay, and Alison Al-Baddawy, Rethinking Counterinsurgency (Santa Monica: RAND Corporation, 2008). also found resonance amongst crackdown policing strategists in South Africa. That is, targeted areas were “flooded” with a vast security force presence in order to “flush out” the perpetrators of various crimes,4242. South African Police Service, Annual Report of the South African Police Service 1 April 1996 - 31 March 1997 (Pretoria: South African Police Service, 1997); Burger, Strategic. and “restore law and order”.4343. Phumla Williams, “Right of Response: In Defence of Operation Fiela,” Daily Maverick, May 22, 2015.

Fifthly, the SAPS have referred to its high density operational approach as an “oil stain strategy”.4444. South African Police Service, Policing. This was originally a French counter-insurgency pacification strategy initially developed in Vietnam in the nineteenth century that proposes that for a government to overcome an enemy, counter-insurgency efforts should be concentrated on securing and developing strategic areas and thereafter the locus of control should be expanded outwards like an oil stain on cloth.4545. Douglas Porch, “Bugeaud, Galliéni, Lyautey: The Development of French Colonial Warfare,” in Makers of Modern Strategy: From Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age, ed. Peter Paret, Gordon A. Craig and Felix Gilbert (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), 376–407; Laurence E. Grinter, “How they lost: Doctrines, strategies and outcomes of the Vietnam War,” Asian Survey 15, no. 12, (1975): 1114–32.

The high-density policing operational approach has also conceivably been driven by organisational dynamics, culture and limitations within the SAPS. Leggett4646. Ted Leggett, The state of crime and policing, in State of the Nation South Africa 2004-2005, ed. John Daviel, Roger Southall and Jessica Lutchman (Cape Town: Human Sciences Research Council, 2005), 165. has suggested that as most SAPS members “have little capacity for more reflective police work, the herding of bodies into mass operations may be the optimal use of available resources.” Similarly, Steinberg4747. Jonny Steinberg, Sector Policing on the West Rand. Three Case Studies (Pretoria: ISS, 2004). (Institute for Security Studies Monograph, no. 110), 2. has emphasised that the police’s preference for high-density crackdown operations has been informed by the SAPS’ “strong, active national centre, and uneven [weak] policing on the ground”, as it is one of the few policing approaches that such a police organisation “can execute with accomplishment.”

The South Africa government has repeatedly emphasised that the SAPS’ operations would be tempered by considerations for the human rights of law-abiding citizens. For example, in his State of the Nation Address in 1996, President Nelson Mandela declared:

The time has come for our nation to choose whether we want to become a law-governed and peaceful society or hapless hostages of lawlessness… The government will use all lawful means to ensure that they [criminals] do not succeed in undermining our social fabric. Law-abiding citizens can rest assured that there are effective mechanisms in place to prevent and punish any rapacious invasion of their lives. 4848. Opening Address by President Nelson Mandela to the Third Session of Parliament, Cape Town, February 9, 1996.

This narrative of discerning criminal othering has been preserved and promoted over the past 20 years, with the SAPS political leadership regularly stating that the police need to take a “tough stance against criminals”4949. Remarks by Minister of Police, EN Mthethwa, MP, at an Institute for Security Studies Conference on “Policing in South Africa: 2010 and Beyond“, Kloofzicht Lodge, Muldersdrift, Gauteng, September 30, 2010. and “uproot the cancer of crime from our communities”,5050. Budget Vote Speech by the Honourable Deputy Minister of Police, Fikile Mbalula, Parliament, Cape Town, July 1, 2009. but this should be “balanced…with the need to ensure our police embrace our human rights culture”.5151. Remarks by Minister of Police, EN Mthethwa, MP, at an Institute for Security Studies Conference on “Policing in South Africa: 2010 and Beyond“, Kloofzicht Lodge, Muldersdrift, Gauteng, September 30, 2010.

In a further attempt to foster legitimacy for these high-density operations, the police’s political leadership, particularly during the tenure of Nathi Mthethwa, have presented these operations as a form of righteous “crusade”5252. Remarks by Minister of Police, EN Mthethwa, at the KwaZulu-Natal Launch of the “Operation Duty Calls“ Festive Season Crime-Fighting Campaign, Durban City Hall, KwaZulu-Natal, December 8, 2009. Remarks by Minister of Police, E.N. Mthethwa, MP at the Mpumalanga Launch of the 2010/11 Operation Duty Calls Festive Season Crime-Fighting Campaign, November 30, 2010. in which the police will strive to “push back the frontiers of evil”.5353. Remarks by the Minister of Police, Nathi Mthethwa, on the Occasion of the Release of National Crime Statistics, September 9, 2010. Similar stances were also adopted at some SAPS stations.

However, the deployment of large numbers of police personnel with varying degrees of experience in dangerous places in the context of ferociously framed crackdown operations that have been spurred on by criminal-hating politicians is not akin to a “surgical strike’, bereft of strike” collateral damage. Several media reports have suggested that the police, as a result of these operations, have on a number of occasions, subjected civilians, including some of the most vulnerable members of society, to serious human rights violations.

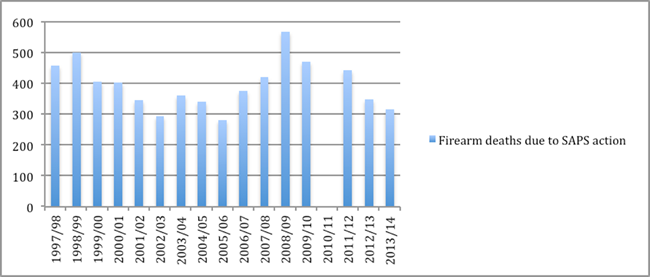

SAPS members have also been responsible for relatively high levels of firearm deaths, which have principally occurred during attempts to apprehend and/or detain suspects, or due to negligence. Some of these deaths took place during high density operations. For example, during Operation Sword and Shield (1 April 1996 and 31 March 1997), more than 100 civilians reportedly died due to police action.5454. South African Police Service, Annual Report 1996-1997. The chart below indicates that deaths due to police shootings declined between 1998/99 and 2002/03 by 42%, but increased dramatically from by 88% between 2005/06 and 2008/09 and then declined by 44% over the next five years.

Source: Independent Police Investigative Directive; David Bruce, “Interpreting the Body Count: South African Statistics on Lethal Police Violence,” South African Review of Sociology 36, No. 2 (2005): 141-159; David Bruce, An Acceptable Price to Pay? The Use of Lethal Force by Police in South Africa. Cape Town: Open Society Foundation, 2010.

A comprehensive, nationally-based study of 2009 mortuary data estimated that there had been 5,513 firearm homicides in South Africa in that year.5555. Richard Matzopoulos, et al. The Injury Mortality Survey: A national study of injury mortality levels and causes in South Africa in 2009 (Cape Town: South African Medical Research Council, 2013). Hence, SAPS members were responsible for between 8% and 9% of all recorded firearm homicides during 2009.

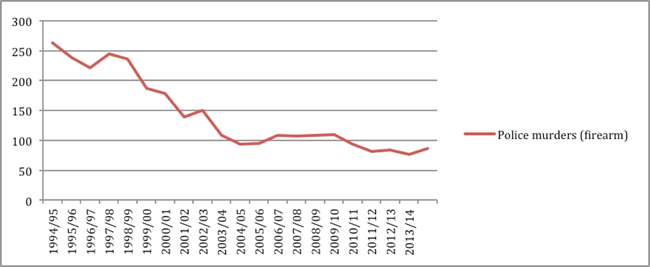

Police in South Africa have also been at high risk of firearm violence. Between 1994 and 1998, 82.3% of all SAPS murders were a consequence of gun shots.5656. Commission of Inquiry Regarding the Prevention of Public Violence and Intimidation Final Report on Attacks on Members of the South African Police. 1994. Following the end of much of the political violence during the mid- to late-1990s the level of police homicides declined considerably from 263 in 1994 to 77 in 2013, more than a 300% decrease over that period of 20 years. Nonetheless, the murder of police personnel has remained an area of grave concern to both the police and its political leadership. For example, in June 2013, in a speech at the funeral of a senior police official, the Minister of Police at the time, Nathi Mthethwa eulogised that the SAPS “are in the midst of a war; a war that has been declared by heartless criminals on our men and women in blue…[and that] we shall ensure that those who kill police officers pay the price accordingly”.5757. South African Police Service, South African Police Service Annual Report 2012/13 (Pretoria: South African Police Service, 2013); Address by the Minister of Police, at the Funeral Service of the Late Major General Tirhani Maswanganyi, SAPS Detective Academy Hall, Hammanskraal, Gauteng, June 27, 2013).

Source: (SAPS)

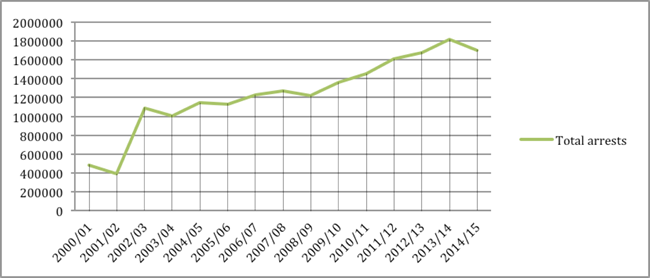

High density policing operations, particularly from 2001, significantly contributed to dramatic increases in the number of arrests by the SAPS (see Chart 3 below). On average 45%, of all arrests were made in the 169 crime hotspot precincts earmarked for high density operations between the 2005/06 and 2009/10 reporting years.5858. South African Police Service, SAPS Annual Report 2005/06 (Pretoria: South African Police Service, 2006); South African Police Service, SAPS Annual Report 2006/07 (Pretoria: South African Police Service, 2007); South African Police Service, South African Police Service Annual Report 2007/08 (Pretoria: South African Police Service, 2008); South African Police Service, Annual Report of the National Commissioner of the South African Police Service for 2009/10 (Pretoria: South African Police Service, 2010). The escalation in the number of arrests also had implications for the prison population. For example, in a briefing to the South African Parliament in October 2004, the Department of Correctional Service reported that Operation Crackdown, which had been the largest high density operation since 1994, had contributed to overcrowding in prisons.5959. Department of Correctional Services, et al., Overcrowding - A Solution-oriented Approach. Presentation to the Select Committee on Security and Constitutional Affairs (Cape Town: National Council of Provinces, October 20, 2004, accessed October 16, 2015, http://pmg-assets.s3-website-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/docs/2004/appendices/041020overcrowding.ppt.

Source: (SAPS)

Between 1995 and 2013/14, the large majority of firearms were recovered during the first 10 years, namely the period during which there was a concentration of high-density operations, with the highest annual seizures being recorded during the 2003 and 2004, a period that corresponds with the implementation of a specialised and intensive firearm-specific operation, titled Sethunya. Thereafter there was a noticeable decline in firearms seizures, with there being an annual average of approximately 10,000 firearms per year. In terms of a provincial breakdown, most firearms were recovered by SAPS were in Gauteng, KwaZulu-Natal and the Eastern Cape and the Western Cape.

Note: SAPS used calendar years to report firearm seizures for the period 1995 to 1998, and thereafter reported for the period, 1 April to 31 March. In addition, SAPS did not make public provincial data on firearm seizures for the period 1999/00 to 2001/02.

Operation Fiela-Reclaim is arguably one of the most controversial operations to date. It was launched in the immediate aftermath of large-scale outbreaks of xenophobic violence in the provinces of KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng in April 2015, and is envisaged to be in place until March 2017. However, the architects of this national operation have more grandiose plans. According to the Cabinet-level Inter-Ministerial Committee on Migration, the intention of this operation has been to target the micro-spaces “which are known to be frequented by criminals”.6060. Statement by Inter-Ministerial Committee on Migration Jeff Radebe, May 17, 2015.

This operation was therefore pursued in order “to rid our country of illegal weapons, drug dens, prostitution rings and other illegal activities”6161. Jenni Evans, “21 arrested in operation Fiela crime sweep in Kagiso,” News24, July 31, 2015. and thereby “reclaiming our communities so that our people can live in peace and harmony”6262. “Operation Fiela not meant to target foreigners: State,” SABC News, June 26, 2015. and to “help create a level of systemic normality”.6363. Richard Poplak, “Breakfast at Fiela's: Jeff Radebe & Co. clear up ‘The Clean-Up’,” Daily Maverick, June 29, 2015. State Security Minister, David Mahlobo suggested that the South Africans were highly supportive of government intention to “clean out those criminal services” throughout the country.6464. Yolisa Njamela, “Operation Fiela to root out criminal elements,” SABC News, April 28, 2015.

The operational blueprint for Operation Fiela-Reclaim, branded the “Multi-Disciplinary Integrated National Action Plan to Reassert the Authority of the State”, penned by the National Joint Operational and Intelligence Structure (NATJOINTS), revealed a deep sense of disquiet within government’s security cluster, namely that the authority of the state had eroded considerably in high-crime communities. According to this plan, the security forces would “dominate and stabilise” focal areas by: pursuing high visibility policing actions; arresting wanted persons; fast tracking criminal investigations; and adopting a zero tolerance approach to lessor forms of criminality, such as traffic offences, operating illegal businesses, selling counterfeit goods, illegal mining, drinking in public and undocumented migrants.6565. NATJOINTS Multi-Disciplinary Integrated National Action Plan to Reassert the Authority of the State, August 19, 2015.

As with previous high-density operations, the SANDF actively participated in the formative stages of Operation Fiela-Reclaim, namely between April and June 2015.6666. Peter Wilhelm, “Operation Fiela: Defence Force quits government’s crime-fighting blitz,” BizNews.com September 7, 2015. However, the military were extracted at the end of June 2015 following concerns raised about the adverse repercussions that their long-term internal deployment would have on the state of democratic governance in South Africa.6767. African News Agency, “SANDF no longer part of Operation Fiela – Mapisa-Nqakula,” The Citizen September 7, 2015; RDM News Wire, “Extension of SANDF’s participation in Operation Fiela unconstitutional: DA,” Times Live July 8, 2015. In addition, there was intensive civil society advocacy concerning the arrest and the apparent disproportionate targeting of undocumented migrants by the security forces under the auspices of this operation.6868. Phillip De Wet, “Operation Fiela's warrantless Searches challenged,” Mail & Guardian Online June 23, 2015; Nomahlubi Jordaan, “Operation Fiela 'demoralises and dehumanises' migrants,” Times Live July 22, 2015.

Similar “pacification” operations have been undertaken in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro by Special Police Operations Battalion (BOPE) and its Unidades de Polícia Pacificadora (UPP) (or Pacification Police Units). This type of police action, which has been undertaken in collaboration with military personnel, was initiated in 2008 in order to impose state control in these marginalised communities that had traditionally been viewed as “enemy territory” by the state as they were mainly governed by criminal groups.6969. Stephaine G. Stahlberg, The Pacification of Favelas in Rio de Janeiro, 2011; Leticia Veloso, “Governing heterogeneity in the context of 'compulsory closeness': The 'Pacification' of Favelas,” in Suburbanization in Global Society, ed. Mark Clapson and Ray Hutchison (Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Ltd., 2010), 253–72; Ben Penglase, “States of Insecurity: Everyday Emergencies, Public Secrets, and Drug Trafficker Power in a Brazilian Favela,” PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review 32, no. 1 (2009): 47–63. The modus operandi has entailed the pre-announced, large-scale, militarised incursion (often with air support) into favelas in an effort to forcibly oust the criminal groups or arrest their members. Thereafter permanent police posts are established, and highly visible armed policing is pursued in an attempt to prevent the criminal gangs from regaining control over these spaces.7070. James Freeman, “Neoliberal Accumulation Strategies and the Visible Hand of Police Pacification in Rio de Janeiro,” Revista de Estudos Universitários 38, no. 1, (2012): 95–126; Alexandre F. Mendes, “Between Shocks and Finance: Pacification and the Integration of the Favela into the City in Rio de Janeiro,” South Atlantic Quarterly 113, no. 4 (2014): 866–73.

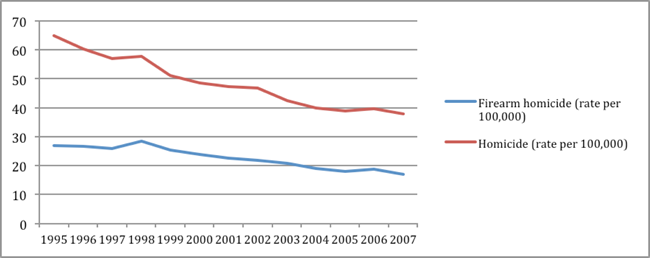

Between 1994 and 1998 South Africa’s firearm homicide rate remained relatively constant, averaging close to 28 per 100,000 people, with the proportion of homicides involving firearms increasing from 41.5% to 49.4%.7171. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), 2011 Global Study on Homicide: Trends, Context, Data (Vienna: UNODC, 2011). In 1998, firearms were reportedly used in 49% of all murders and in 75% of all attempted murders. Close to half of all firearm homicides in 1998 took place in two provinces, namely KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng.7272. Chetty, “The role”.

From 1998 South Africa’s firearm homicide rate steadily declined to 17 per 100,000 in 2007 (a 40% reduction), with the total number of firearm homicides in South Africa shrinking from 12,413 to 8,319 over the same period (a 33% reduction).7373. UNODC, 2011 Global. By 2008 sharp force injuries had become the leading cause of non-natural death (and therefore homicide too) in South Africa (13.6% of total non-natural deaths) followed by firearms (10.8% of total non-natural deaths). This trend was maintained in 2009, with sharp force injuries (41.8% of all homicides) continuing to be the leading cause of homicide7474. Homicides accounted for 36.2% of all non-natural deaths in 2009 according to mortuary data. followed by firearms (29% of all homicides).7575. Matzopoulos, et al. The Injury.

Source: (UNODC, 2011)

The decline in homicide has principally been attributed to the FCA by a variety of public health researchers.7676. Richard Matzopoulos, Mary L. Thompson and Jonathan E. Myers, “Firearm and Nonfirearm Homicide in 5 South African Cities: A Retrospective Population-Based Study,” American Journal of Public Health, Online January 16 (2014): e1–e6; N.M. Campbell, et al., “Firearm injuries to children in Cape Town, South Africa: Impact of the 2004 firearms control act,” South African Journal of Surgery (SAJS) 51, no. 3 (August 2013): 92–6; Naeemah Abrahams et al., “Every Eight Hours: Intimate Femicide in South Africa 10 Years Later!” South African Medical Research Council Research Brief (Cape Town: Medical Research Council, 2012). However, the firearm homicide rate began to significantly decline from 1998/99, five years before the enactment of the FCA. As mentioned above major high density policing operations were introduced and were regularly sustained from 1996/97 onwards. In addition, these operations resulted in large-scale arrests, particularly of individuals at high risk of committing violent acts, as well as the mass seizure of illegal firearms from crime hotspot places. It is possible that this combined effect may have been a key contributor to the initial and continued decline (along with the implementation of the FCA) in firearm homicides in South Africa.

In the context of high levels of firearm violence in South Africa this article has explored the SAPS’ attempts to leverage effectual control over the proliferation and misuse of firearms. A key strategy has been that of militarised high density policing operations in the context of a “war on crime” ideology. Through roadblocks and cordon-and-search interventions police seized very large quantities of firearms and ammunition from high crime areas (where firearm murders tended to be concentrated), and arrested thousands of individuals (mainly young men), for a range of crimes, including being in possession of unlicensed firearms. Therefore, significant numbers of high risk potential perpetrators of firearm violence, as well as the instruments of such violence, were extricated from such high crime areas. Declining trends in violent crime between 1998/1999 and 2010/2011 suggest that the SAPS operational efforts may have contributed to reductions in firearm homicide. However, such operations have seen the police wield extensive and invasive powers, which has led to the eroding of the Constitutional rights of many residents in high crime areas, who have often been subjected to heavy handed police actions and at times treated in an undignified fashion. Some individuals have also been injured, or have lost their lives as a result of these police operations.