A timeline of stories, legal and policy responses and analyses

The ‘Covid-19 and the Constitution’ timeline is a web-based resource conceptualized and developed by Center for Health Equity, Law and Policy in collaboration with Justice Adda and Vaibhav Bhawsar. It documents Indian legal and policy responses to the pandemic and contextualizes them with fundamental rights guaranteed in the Indian Constitution. The timeline also offers illustrated personal narratives and experiences of citizens’ varied struggles, along with critical commentary on emerging issues that implicate fundamental rights. Through this paper, the authors elucidate on the motivations, aims and methodologies which undergird the project. The authors hope that the project will serve to shape rights-based responses to future health challenges, in India and elsewhere.

The sudden onslaught of the Covid-19 pandemic brought with it a slew of law and policy directives that wrought profound, incalculable and enduring change in people’s lives. The Covid-19 and the Constitution timeline11. Covid-19 and the Constitution, Homepage, 2020, accessed December 6, 2021, https://covid-19-constitution.in. was created as a response to this avalanche of instructions to document them and to inquire as to whether policy and legal responses were aligned with the obligations enshrined in Part III – Fundamental Rights of India’s constitution – the litmus test for justifiable legislation. While the nature of the emergency and the imminent dangers of Covid-19 required reasonable restrictions on some of these rights, for instance the freedom of movement, it became important to reflect on whether a balance had been struck between enhanced powers of the state during health emergencies such as the pandemic and the fundamental rights of people.

Experience has shown that strategic deployment of law and policy can play a critical role in meeting health challenges if done in a manner that is evidence-informed, rational, rights-based, transparent and accountable. What has clearly come to light while dealing with HIV/AIDS in India and elsewhere is that rights-based advocacy, rooted in Part III of the Constitution and various principles of the universal right to health, results in robust legal responses put in place by the state but kept in check by its citizenry. With these goals in mind, the Centre for Health Equity, Law & Policy22. Centre for Health Equity Law & Policy (C-HELP), Homepage, 2021, accessed December 6, 2021, https://www.c-help.org. in collaboration with Justice Adda33. Justice Adda, Homepage, 2021, accessed December 6, 2021, https://www.justiceadda.com. and Vaibhav Bhawsar44. Vaibhav Bhawsar, Homepage, 2021, accessed December 6, 2021, https://www.recombine.net. launched the Covid-19 and the Constitution timeline on June 7, 2021. It is a contemporary, visual, interactive repository of law, policy, experiences and analyses.

This portal aims to respond to several questions that have been posed since early 2020 and that prompt several more: What legal and policy mechanisms have been adopted to control the pandemic? What is the role of the government in discharging its positive obligation to the people to control the pandemic? Are the actions taken legitimate, proportionate, evidence-based and thereby justified in limiting fundamental rights? What lessons can be learnt from this experience to better cope with future challenges while preserving inviolable aspects of the constitution? The timeline seeks to examine and reflect on the last year through the most indispensable lens of fundamental rights, prodding the user to contemplate how to balance the freedoms that are essential to democracy with roles and responsibilities that are expected of a range of actors. This is done through three key components.

First, the landing interface of the timeline presents a chronology of legal or policy responses that have emerged from the central government and (three) state governments, and their intersection with fundamental rights. Second, the section ‘Stories of Covid-19’ catalogues a selection of personal experiences of people from diverse social and geographical locations that reveal journeys of extreme pain and fortitude. It humanizes the wide-ranging impact of what has been endured and inflicted, while coaxing the reader to consider how fundamental rights (or lack thereof) play a crucial role in serving citizens and public health interests. Third, the ‘Analyses’ component of the timeline contains critical commentary by experts on various themes that involve fundamental rights and the Constitution.

To enable such layered reading, the timeline allows users to easily consult a wide, constantly updated database of legal and policy responses, complete with comprehensive navigation and filtered search options. Each response is categorized using criteria such as the fundamental right(s) affected, origin of response (state judiciaries, government ministries and departments, etc.), type of response (circulars, regulations, etc.), areas of impact (education, health, etc.) and the impacted jurisdiction (geography). The timeline provides interactive control options to further search and filter these categorizations to identify patterns and relationships in the responses.

In addition, the timeline juxtaposes the two other types of content to help contextualize and humanize this slew of data. Stories of impact take the form of articles with images and other rich media to evocatively express the impact. Expert analyses and commentaries lend academic insight and further depth to these stories. Together, the sections constitute a holistic, dynamic resource that is meant for use and exploration by not only lawyers and law students, but anyone wishing to track India’s response to Covid-19.

The timeline’s home page offers a visualization of the plethora of legal and policy decisions taken every day since Covid-19 was first identified, represented as grey dots, and uses colour-coded bands to indicate the fundamental rights that they impact. The timeline is visually appealing and immediately draws the user’s attention to this tacit relationship between rights and policy. As users move toward other sections, they find illustrative representations of legal issues in various modalities.

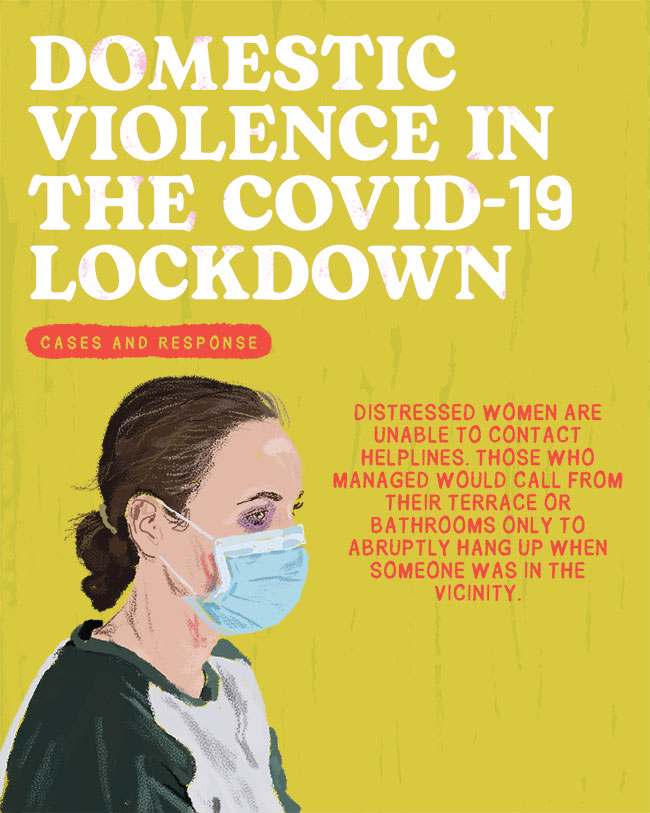

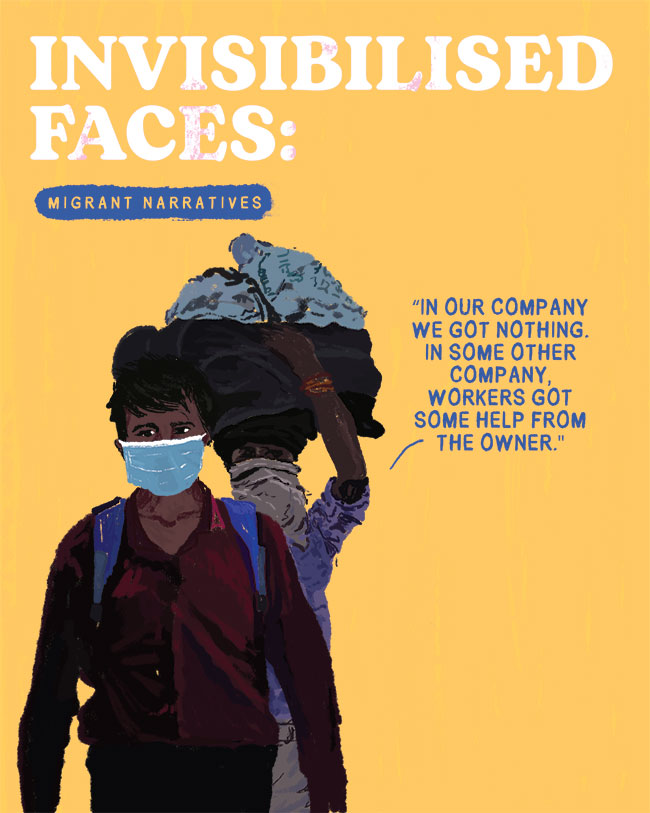

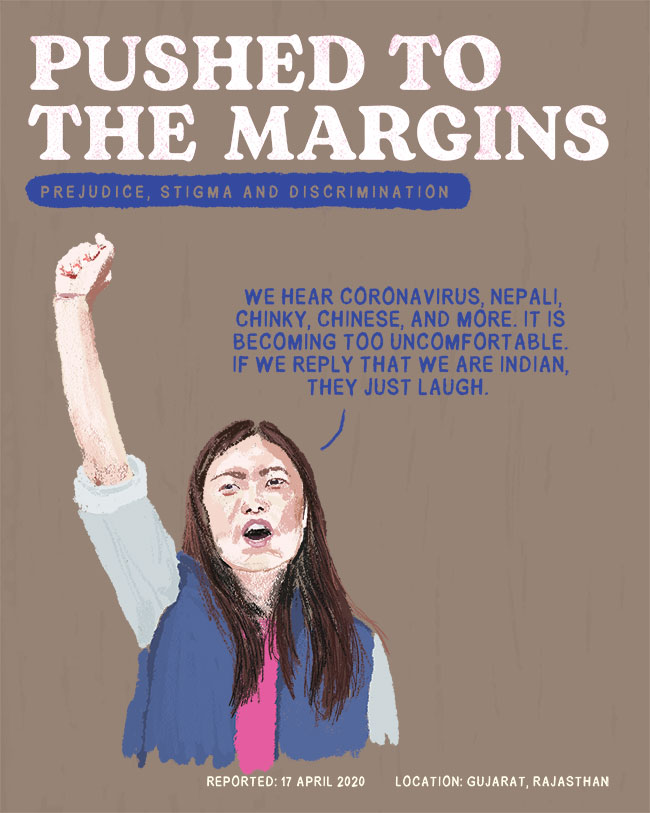

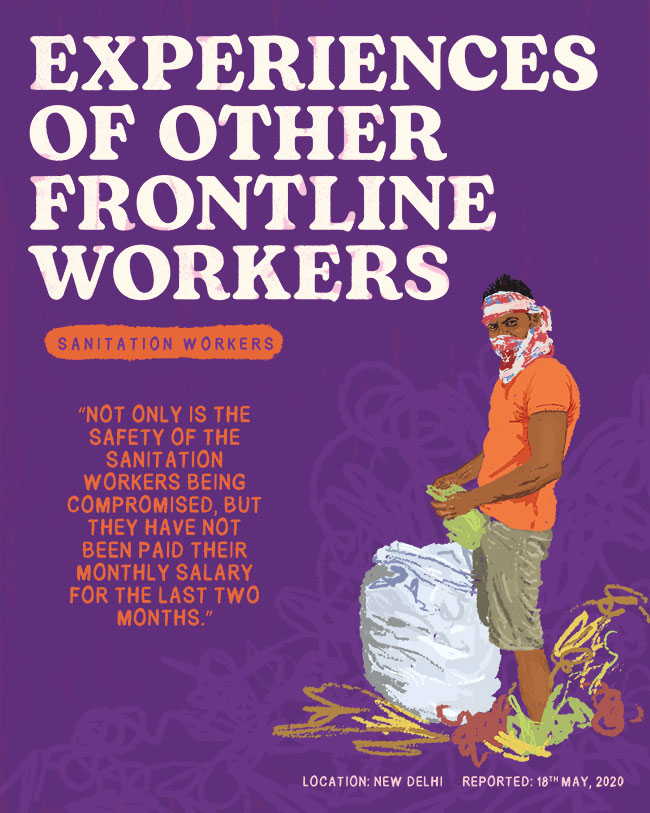

All the analyses on the timeline are attached to an illustration that encapsulates the tone of the article. Stories are almost entirely visual. Having observed the grave toll the first and second wave of Covid-19 took on India and the effect of reducing deaths to a daily statistic, we were concerned with finding ways to humanize the challenges people faced during the course of the pandemic. The overwhelming influx of data, statistics and death tolls had made our perception of illness and loss of life numerical and mechanical. Behind these statistics, there was deep trauma, grief, anger, rage, helplessness and frustration, which were not adequately addressed or assuaged by policy directives. Illustrated stories, and the timeline as a whole, thereby became an opportunity to connect with human experiences beyond mere numbers and truly put into perspective the gravity of loss and devastation that the pandemic has wrought across the country.

At the outset, it was clear that it would be impossible to gather enough stories to get a comprehensive picture of the vast suffering caused by the pandemic all across India. Instead, we used a selective case study approach, picking out a range of stories in which each one illustrates a different issue and perspective on Covid-19. This allowed us to concentrate on individuals’ experiences of the pandemic, rather than us trying to tell a general “story of the pandemic” through a universal narrative.

We drew on news reporting throughout the pandemic to identify compelling stories that each told a truth about individual suffering and institutional failings. From this pool of stories, we selected certain ones to ensure geographic reach, a diversity of voices and a range of experiences. For some stories, such as one on intimate partner violence and another on the plight of grassroots social health workers, we employed primary research methods, including hosting an informative consultation with first responders and legal NGOs (for the former) and conducting a few telephone interviews with key informants in the regional language (for the latter).

While this methodology allowed us to tell individuals’ stories in a more personal way, this approach also meant that our own biases and preferences entered the selection process. Thus, we may have unintentionally excluded certain voices or placed more emphasis on parts of the narrative that particularly resonated with us. While this subjectivity is arguably unavoidable in a project like this, it should certainly be kept in mind by anyone reading the narratives. The timeline presents important perspectives on the Covid-19 pandemic but it is by no means the complete picture.

The stories chosen for the timeline were ones capable of representing a diverse array of individual rights that were eroded during this time. The pandemic and state response thereto posed a unique set of challenges to the fundamental rights to life, livelihood, liberty and dignity. Stakeholders from different social and economic groups and across income levels bore the brunt of the pandemic and the effects of the state’s management of the pandemic did not spare the rich or the poor. However, it was the marginalized and already vulnerable populations that especially struggled for access to information, money and basic medical facilities. That led us to focus on the plight of migrants, women and the underprivileged whose issues were “pushed to the margins” of discourse and policy attention. Their struggles were complicated by an orchestrated campaign of false and often contradictory information about the spread of the virus and remedies for its cure that spurred fear and widespread panic and ensured the complete disruption of normal life. By covering the situation of the most affected stakeholders throughout the entire pandemic – from the starting phases of the first wave through the consequent economic lockdowns – we hope to convey the huge costs to the Indian economy and society caused by the pandemic and the state’s response.

Statements by individuals were interwoven with a description of how these issues manifested themselves during the pandemic. In general, the narratives were broken up into slides accompanied by graphics. The exception to this was the story on domestic violence, which was presented in its original form as a set of videos.

We chose to format the narratives as slides so they could be easily shared on social media, particularly on Instagram and WhatsApp, to make them more accessible. Breaking up the narrative in this fashion also allowed us to highlight direct quotations taken from the individuals involved. The use of graphics instead of photos signalled that these voices were representative of a much wider problem and that the experience of the individual was a shared one and not particular to them. The timeline carries these intentionally vague but powerful graphics at various points to serve as a necessary reminder that the rights violations being addressed and presented belong to real people, are drawn from real experiences and have impacted real lives in immeasurable and irreversible ways.

The resource is built to facilitate research and present information and experiences from all facets of the pandemic, legal or otherwise. The repository of legal and policy responses can aid in the academic and statistical analyses of Covid-19 in India. It makes a plethora of original official documents accessible in one place through original source links and archived formats in case the original is taken down, making cumbersome legal search easy and comprehensive. A user can sort by date, location and impact areas to get to a policy document they need. There is a comprehensive visual guide, accessible as a separate tab on the website menu, which outlines all its features and simplifies navigation. Broadly, the timeline has an advanced search function, the possibility of filtering and sorting through all available entries across the three sections, and separate index pages for these sections.

The advanced search and filter functionality may be toggled by clicking on the magnifying glass icon to the left of the home page. This feature allows users to filter through the legal and policy responses, stories and analyses featured on the timeline using an advanced word search, a date range, recency, affected fundamental rights and areas of impact, source of the response, jurisdiction and much more. One may also run a simple keyword search which quickly sifts through over a thousand item titles. The index for analyses and stories makes it easier to access all of them in one place.

The ease of access makes the timeline a resource for not only legal researchers but also journalists and reporters, students, teachers, analysts and civil society in general. The analyses section offers more extensive reading on legal issues. ‘Stories of Covid-19’ contains more visual, first person accounts of loss, grief and hindrances that can both act as anecdotal supplements to academic research and exist in isolation as a reminder of the suffering people endured during the pandemic.

Through the resources already generated, we hope that the timeline can provide an impetus to civil society action, whether in the form of strategic litigation or policy reform to address the rights infringements that have been identified in the analyses. The timeline also offers materials for campaigning, namely those that give visibility to the pain and suffering that has been caused in people’s lives by both the pandemic and on account of the responses of the state. We also envisage the timeline to be a living resource that will continue to record and engage with the ways the pandemic is bringing about new challenges to the exercise of fundamental freedoms.

Some of the barriers to the project include the need for a stable internet connection and a laptop/desktop to access the timeline and use it meaningfully. These are challenges where internet connections are still limited and most people use mobile devices to access the web. By distilling the content to disseminate it through social media, we hope to make it more accessible. Additionally, the resource is currently only in English, an aspect that we are seeking to address by introducing regional translations. We also aim to ensure that content such as stories and analysis pieces can be shared through other mediums where they can be accessed offline, for example, as PDFs. Currently, the legal and policy responses are mainly from only a few states, chosen for their unique methods of responding to the pandemic, which limits the timeline’s capacity to provide a comprehensive pan-India picture. Lastly and in general, low data literacy levels amongst the public pose a hindrance to understanding how to leverage data-supported advocacy tools such as this timeline to affect social change. Hence, we hope that part of the next steps of the project can include building outreach and community events, to strengthen the reach and utility of the platform.

Although titled Covid-19 and the Constitution, the resource is not intended to be only focussed on the law and designed for lawyers. It is meant to present the loss and suffering during the pandemic in a visual and jurisprudential light instead of reducing them to mere statistics. So far, the response to the timeline has been optimistic and positive, with constructive feedback. As people from an array of professions and age groups keep using it, they make new discoveries in navigation, face new roadblocks and send new suggestions on how to strengthen it. Based on this feedback, we intend to keep optimizing the resource until it is comfortable and efficient for all kinds of users, young or old.