The Challenges to Accountability in Peru

The world has witnessed a dramatic number of laws protecting freedom of information (FOI) in recent years. This paper examines the role of FOI legislation in allowing society to address past atrocities as well as the obstacles they face in doing so. The experience of access to information in Peru is considered, along with recent obstructions to access and the response from investigators, judges, and civil society organizations.

In recent years, the world has witnessed a dramatic upsurge in the number of laws protecting freedom of information (FOI) (BANISAR, 2006; MENDEL, 2009; MICHENER, 2010). This explosion of FOI legislation has occurred rapidly and, as a result, scholars have been slow to develop the theoretical implications of this phenomenon. Surprisingly little is known about the factors that lead to the enactment of FOI laws or the variables that affect the levels of State compliance once enacted. Perhaps more importantly, the effects of FOI laws on issues of governance such as corruption and human rights are unsettled.

This article will examine the role of FOI legislation in allowing society to pursue accountability for past atrocities as well as the obstacles faced in so doing. It will focus specifically on the experience of Peru, where access to public information has been a key factor in the pursuit of justice for atrocities committed by State actors during that country’s internal armed conflict, but where such access has been restricted, especially in recent years.1 This has been a key factor in the dismissal of hundreds of cases of human rights violations by legal authorities. We discuss some of the ways in which State actors have hampered access to public information and, perhaps not coincidentally, progress towards exposing and prosecuting heinous acts from Peru’s darkest period.

This paper draws on research conducted by the lead author on the status of criminal prosecution of cases of grave human rights violations in Peru since 2009. This research culls data from diverse sources, including from the Public Ministry, the Ombudsman’s Office, judicial registers, archives of human rights organizations, and the press. One of the investigation’s early findings was that there was no central registry of ongoing human rights prosecutions on the part of any public or private entity. As a result, and in close collaboration with human rights organizations that represent victims in these cases, the lead author constructed a registry of human rights prosecutions in process, as well as sentences produced by Peruvian courts in such cases.2 In addition, the lead author has observed in situ numerous trials, reviewed publications, reports, and news articles relating to these cases and the broader judicial process, and interviewed judges, prosecutors, and other judicial operators, human rights lawyers, survivors and relatives of victims, and external observers.3

What this research shows is that since beginning its democratic transition in 2000-01, while the Peruvian State has made important efforts to provide truth and justice for thousands of victims of State-sponsored human rights violations, significant obstacles to achieving accountability remain. This paper focuses on one such obstacle: the refusal on the part of the Peruvian State to comply with the public’s right to access information about historic human rights violations. The paper closes with some broad conclusions and recommendations concerning the free exercise of the right to information.

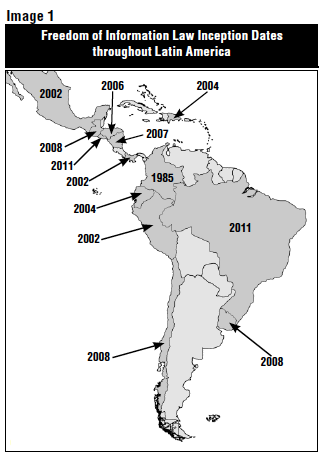

In 1990, the right of access to information was hardly a universally accepted concept. At that time, only 13 countries in the world had adopted legislation protecting and institutionalizing a right to access government information; only one of those was in Latin America.4 By 2003, this number had more than tripled, to 45 worldwide. This pattern of countries enacting FOI legislation, alternatively labeled an “explosion,” (ACKERMAN; SANDOVAL-BALLESTEROS, 2006) or “revolution,” (MENDEL, 2009) has continued into the second decade of the 21st century. Following enactment of FOI legislation in El Salvador (March 2011) (TORRES, 2011) and Brazil (November 2011) (THE GLOBAL NETWORK OF FREEDOM OF INFORMATION ADVOCATES, 2011) over 90 countries worldwide and 13 countries in Latin America now have laws establishing a right to access government information (see image one).

Compiled by the authors5

While Colombia enacted the first Latin American FOI legislation in the mid-1980s, the region’s wave of legislation began in earnest in 2002 with enactment in Mexico, Panama, and Peru. Ecuador and the Dominican Republic soon followed suit, enacting laws in 2004. Honduras in 2006, Nicaragua in 2007, Guatemala, Chile, and Uruguay in 2008, and Brazil and El Salvador in 2011 have all joined the club of countries with FOI legislation on the books. While Argentina has not succeeded in passing FOI legislation, legislative decree law 1172, passed in 2003, establishes access to information for the Executive branch of government.

As national legislatures have moved towards institutionalization of access to information, international law, particularly in the Inter-American system, has produced important jurisprudence supporting this development. In 2006, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACtHR) ruled in the case of Claude Reyes vs. Chile that the government of Chile had violated the rights of Fundación Terram, an environmental non-government organization, to access information about a major logging operation in that country.6 This ruling represented the first “international tribunal to recognize a basic right of access to government information as an element of the right to freedom of expression” (OPEN SOCIETY FOUNDATIONS, 2009).7

Mack Chang vs. Guatemala, a 2003 case decided by the Inter-American Court several years prior to the Reyes case, established severe limitations on the ability of the State to restrict access to public information. The Court ruled:

In cases of human rights violations, the State authorities cannot resort to mechanisms such as official secrets or confidentiality of the information, or reasons of public interest or national security, to refuse to supply the information required by the judicial or administrative authorities in charge of the ongoing investigation or proceeding.

(INTER-AMERICAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS, 2006).

In other words, information related to trials of grave human rights abuses may not be withheld on the grounds of national security.

More recently, the IACtHR ruled against Brazil in the 2010 case of Gomes Lund vs. Brazil (Guerrilha do Araguaia). In this case, the Court ruled that Brazil’s refusal to provide information on the whereabouts of a large group of leftist guerrillas disappeared during that country’s military dictatorship (1964-1985) violated the right to information enshrined in article 13 of the American Convention on Human Rights. The court went further in this case, writing that Brazil had also violated the “duty to investigate,” to provide “access to court,” and crucially, that Brazil’s amnesty law is “incompatible with the American Convention and void of any legal effects” (OPEN SOCIETY FOUNDATIONS. 2010).8

These cases help to illustrate the evolving definitions and concepts behind freedom of information. Toby Mendel argues that the term “freedom of information” is rapidly being replaced by “right to information” among activists and officials alike. As an example, he cites the 2005 FOI law in India, which expresses a “right” to information in its title (The Right to Information Act) (MENDEL, 2008; MENDEL 2009, p. 3). Interestingly, the Inter-American Dialogue report on a 2002 conference on access to information in the Americas argues that access to information is best understood not as an individual “human” right but as a matter of public interest – “a prerequisite for democracy, open debate, and accountability” (INTER-AMERICAN DIALOGUE, 2004, p. 13). Others, (ACKERMAN; SANDOVAL-BALLESTEROS, 2005) recognize an increasing discourse around FOI as positive, rather than negative freedoms. In other words, rather than understanding FOI as a freedom from censorship and control, we should conceptualize it as a freedom to achieve some particular end – knowledge of a loved one’s fate or of an ex-army general’s involvement in crimes against humanity, for example.

What this school of thought offers is a conceptualization of a right to information couched in terms of other more established or widely recognized civil and political rights. The Claude Reyes vs. Chile and Gomes Lund vs. Brazil cases cited above hold that access to information should be guaranteed as a necessary ingredient of other rights that are enshrined in international law: namely, the right to freedom of expression and the right to participation enshrined in the American Convention on Human Rights. Alasdair Roberts furthers this line of thinking by considering the right to access information in light of a spread of “structural pluralism” in government (ROBERTS, 2001). To synthesize his argument, the continued delegation of government functions to corporations and other non-government organizations could pose a challenge to the ability of a “right” to information to result in access to information itself unless it is grounded in other rights: rights to freedom of expression and participation – rights which generally have more legal purchase in laws and constitutions in the Americas. In the case of Peru, as we explain below, the right to access public information is articulated as both a right in and of itself, and as a right implied and inherent in the exercise of other constitutional rights.

The question of how to define and operationalize the concept of a right to access public information is of particular relevance in such post-conflict settings as Peru. Between 1980 and 2000, Peru was consumed by a devastating internal armed conflict involving the State and two insurgent groups (the Maoist Shining Path and the more traditional Tupac Amaru Revolutionary Movement or MRTA). That conflict resulted in nearly 70,000 deaths concentrated primarily in rural indigenous communities.9 Following the dramatic fall of President Alberto Fujimori’s government in 2000, the country embarked on a process of transition, seeking to reestablish democratic governance and adopting key transitional justice mechanisms to address the legacies of past violence. As we shall see, criminal trials for massive human rights abuses have played an important part in this process.

After ten years of authoritarian rule under Alberto Fujimori, the regime collapsed in November 2000 following a major corruption scandal that prompted Fujimori to flee to Japan, from which he faxed his resignation. In the context of a democratic transition under Valentin Paniagua (November 2000-July 2001) and then Alejandro Toledo (2001-2006), the Peruvian government made a concerted effort to move away from the authoritarian tendencies of the previous ten years and consolidate a nascent democracy. This included, among other measures, reforming Peru’s electoral institutions and the Judiciary (which had been thoroughly politicized during the Fujimori period), reinserting Peru into the Inter-American system of human rights protection (Fujimori removed Peru following a series of unfavorable rulings on human rights issues), the creation of a truth commission to examine human rights violations committed during the 20-year conflict, and new measures to develop greater transparency in government.

Important among these measures was a commitment to transparency and openness that included development of the Law on Transparency and Access to Public Information (hereafter the Transparency Law). The Transparency Law took great steps to institutionalize and protect the right of access to information, enshrined in the 1993 Constitution. Article two (clause 5) of the Constitution states: “All persons have the right: […] to solicit information that one needs without disclosing the reason, and to receive that information from any public entity within the period specified by law, at a reasonable cost” (PERÚ, [1993], 2005).

The Transparency Law, passed in 2002, mandates that any documentation funded by the public is considered public information and should therefore be publicly accessible.10 It also provides for proactive publication on the part of the State, including the publication – via internet – of budget information, procurement records, and information about official activities, among other things. Citizens can petition any government agency or private organization that provides public services or receives public funds. Importantly, article 15 of the Transparency Law specifically exempts information related to human rights abuses from classification on any grounds: “No se considerará como información clasificada, la relacionada a la violación de derechos humanos o de las Convenciones de Ginebra de 1949 realizada en cualquier circunstancia, por cualquier persona.” (PERU, 2003).11 The Peruvian law stipulates that petitioned bodies must respond to requests within seven working days.

The process of appeals for denied requests for information provides for an internal process but not an external one. In other words, while petitioners can appeal to a higher department within the agency where the request was made, the law does not provide for an independent body with the capacity and authority to adjudicate such cases. While the Peruvian Ombudsman does often investigate cases of non-compliance, it has no binding power. These cases must be appealed through the court system based on the right of habeas data.

The Peruvian law does not require government bodies to provide assistance to petitioners who need it. This affects disabled or handicapped individuals as well as those whose first language is not Spanish, a sizeable population in Peru. The lack of an independent oversight commission, such as Mexico’s Federal Institute for Access to Information, makes the appeals process even more cumbersome and likely hinders the development of a culture of transparency. This is particularly true considering the broad nature of information exempted by the law, divided into three tiers. First, “secret” information, addressed in article 15, generally includes military and intelligence information. “Reserved” information, addressed in article 16, includes information pertaining to the police and justice systems. Finally, “confidential” information, addressed in article 17, covers a broad range of exemptions, including all information protected by an act of Congress or by the Constitution. In response, in early 2013 the Ombudsman’s Office proposed the creation of an independent oversight commission. This initiative was met with enthusiastic support from civil society.12

As with the process of consolidating Peru’s democracy, the early criminal prosecutions for human rights violations began on the ruins of the Fujimori regime. In March of 2001, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights ruled that the State was responsible for the 1991 killing of 15 people in the Barrios Altos neighborhood of Lima and ordered an investigation into the crime and prosecution and punishment of those responsible. As part of the Barrios Altos ruling, the Inter-American Court overturned Peru’s 1995 amnesty laws, paving the way for some of the first indictments related to human rights abuses during the 20-year internal conflict.

Soon after the Inter-American Court ruling, interim president Valentin Paniagua announced the creation of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (the “CVR”). The CVR was endowed with a broad mandate to investigate and provide an official memory of the internal conflict. In addition, the CVR established a legal unit to investigate human rights violations and recommend cases to the judicial authorities for criminal prosecution. As part of the final report, released in 2003, the CVR handed over 47 case files to judicial authorities for criminal prosecution. While some of these cases implicated leaders of the two insurgent groups, the bulk involved State agents, who to date had not been prosecuted or punished for these crimes.

As part of its extensive recommendations, the CVR urged the government to create a special system of prosecutorial offices and tribunals to adjudicate human rights cases. Development of this new prosecutorial system was slow, finally taking shape in late 2004 and early 2005. Today, seven special prosecutorial offices operate in key jurisdictions (two in Lima, two in Ayacucho, and one in Huancavelica, Huanuco, and Junín) and several tribunals have also been established, though a Supreme Court directive stating that all cases in which there are two or more defendants should be transferred to Lima has resulted in most cases being adjudicated by the Special Criminal Court (Sala Penal Nacional) in Lima. The first rulings on cases of human rights abuses were handed down in 2006.

In its first years, the special system to investigate and prosecute human rights violations handed down a number of sentences in a handful of emblematic cases. One early verdict – the case of disappeared student Ernesto Castillo Paez – convicted four police officers and recognized the crime of forced disappearance as a crime against humanity. The most well-known case within Peru was undoubtedly the trial of former president Fujimori. Extradited from Chile in September 2007, the former president was put on trial later that year, and in April 2009 was convicted and sentenced to 25 years in prison for a series of grave human rights violations, which according to the sentencing judges, constitute crimes against humanity in international law (BURT, 2009; AMBOS, 2011).14

The lead author closely monitored the Fujimori trial and upon its conclusion developed a collaborative research project with local human rights organizations to analyze the status of other pending human rights cases stemming from the 20-year internal armed conflict. TheDefensoría del Pueblo (Ombudsman’s Office) monitors the 47 cases recommended by the CVR for criminal prosecution plus an additional 12 cases, but anecdotal evidence suggested that the case universe was much larger, and little was known about the evolving status of ongoing criminal investigations and trials. In partnership with Peruvian human rights NGOs, the lead author developed a database of active cases, drawing on information from the NGOs themsleves, the Public Ministry, and the Ombudsman’s Office, to get a better grasp of the status of criminal investigations and trials. This became a more urgent task by 2010 after a series of controversial acquittals by the National Criminal Court, sustained efforts to impose a new amnesty law and shut down criminal prosecutions, as well as anecdotal evidence suggesting political interference in the judicial process.

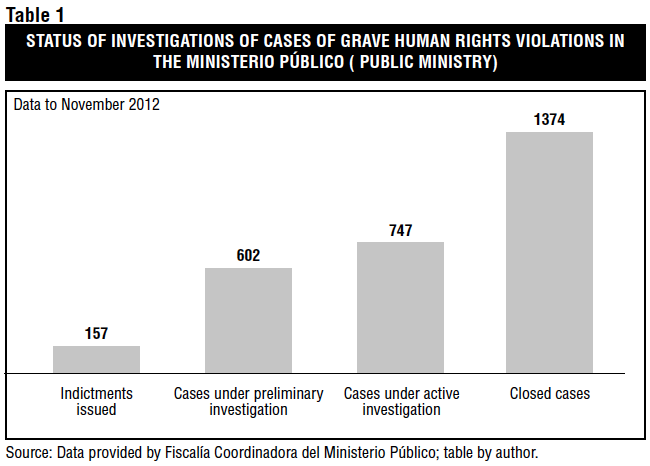

To summarize, the research findings indicate that the case universe is much larger than expected (2,880 complaints filed with the Public Ministry); advancing much more slowly than realized (the Public Ministry has brought charges in only 157 cases, or five percent of the total); a large number of cases remain under preliminary investigation (602) or active investigation (747) (47 percent); and a significant number of cases – 1,374 or 48 percent – have been closed or dismissed, a large number, according to interviews with Public Ministry officials, due to insufficient information about the identity of the perpetrators (See Table 1). Regarding sentences, a significant number of rulings have resulted in acquittals, some of which are highly circumspect (of 50 verdicts identified as of this writing, one or more defendants have been convicted in twenty15 while all defendants have been acquitted in thirty) – though a significant number of these rulings have been overturned on appeal by the Supreme Court and have gone to retrial.16 The overall number of individuals acquitted is much higher than those convicted (133 acquitted and 66 convicted to date).17

Human rights organizations have been sharply critical of several of these sentences, suggesting that judicial authorities are failing to properly weigh key evidence, ignoring international law, and even prior sentences handed down by Peruvian courts (RIVERA, 2009, 2012). For example, while the Fujimori verdict establishes that in human rights cases it is unlikely that written orders exist therefore circumstantial evidence may be used to substantiate convictions, the National Criminal Court has ruled in a number of recent cases that since no written order exists indirect (or intellectual) authorship cannot be established, leading to the acquittal of military officers in command positions. Additionally, while the Fujimori verdict validates the finding of the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission that there were systematic violations of human rights in certain places and at certain times, in recent rulings the National Criminal Court fails to take into consideration such findings, stating instead that massacres and other violations of human rights were mere “excesses” committed by low-ranking military personnel; this too has served to justify acquittals of commanders in a number of cases.

As of this writing there are more than a dozen cases in public trial. Some of these involve highly emblematic cases, including the 1985 Accomarca massacre of 69 peasants (mostly women, elderly, and over 20 children); the case of arbitrary detention, torture, and forced disappearances that took place in the Los Cabitos military base in Ayacucho; the case against “Agent Carrion,” e.g. intelligence agent Fabio Urquizo Ayma whose personal diary was discovered upon his arrest in 2001 in which he describes his involvement in the murder of 14 people, including journalist Luis Morales Ortega and former mayor of Huamanga Leonor Zamora; and the retrial of the 1991 Santa Barbara massacre of 15 people.

Thus, while some important cases have been successfully prosecuted and important sentences handed down, there are other concerning trends evident in Peru. Ten years after the CVR’s Final Report and its recommendation to prosecute grave human rights violations was made public, the pace and progress of investigations by the Public Ministry is excessively slow and in some cases seem paralyzed, a very small number of indictments against alleged perpetrators have been handed down in light of the total case universe, and nearly half of all denunciations have been dismissed. Once indictments are issued, the Judiciary must conduct its own investigation before moving to the public trial phase; here are often long delays at the stage, sometimes measured in years, and the pace of cases once in public trial is painstakingly slow. For example, the Accomarca trial began in November 2010 and is not expected to culminate until sometime in 2014. Finally, the series of acquittals in recent years has generated severe criticism of the tribunals adjudicating human rights cases.18

While the development of Peru’s transparency law was impressive on paper, the degree of actual transparency in the country – particularly regarding cases involving human rights abuses – is poor. Groups and individuals who track compliance with transparency norms and regulations in Peru paint a worrisome picture. The Peruvian civil society group Instituto de Prensa y Sociedad (Press and Society Institute) cites a mere 17 percent response rate to the over 40.000 requests for information filed (this number tracks all requests to all agencies) in the first year of the law’s existence. Meanwhile, 68 percent of requests were incomplete or failed to meet the law’s timeframe and fully 32 percent of requests met with no response at all (MENDEL, 2008).

The culture of transparency is particularly weak in the Defense Ministry, the Armed Forces, the National Police, and the Ministry of the Interior. This is unfortunate in the case of investigations into past human rights violations since the vast majority of individuals of interest serve or served in one of these agencies.19

Problems that stem from obstructions within these agencies generally fall into three categories. First, in cases involving members of the Peruvian armed forces (which the vast majority do), prosecutors and researchers lack information critical for identifying those responsible for human rights violations. The Public Ministry typically seeks the following types of information: the names of the heads of the military bases that operated in areas under a state of emergency; the names of the personnel who worked in these military bases, as well as their service records, annual evaluations, and reviews for promotion; documents referring to military operations, dispatches of military patrols, and lists of detainees; and manual, directives, intelligence reports, and other documents produced to guide in the conduct of counterinsurgency operations. Second, where the identity of suspects has been established, judges and prosecutors encounter delays and unnecessary obstructions in receiving statements from the accused. Finally, where responses are received, they are generally “unsatisfactory” in that they are unnecessarily slow in coming, incomplete, or denied on tenuous grounds (DEFENSORÍA DEL PUEBLO, 2005, p. 149).

According to the Fiscal Coordinador de las Fiscalías Superiores y Penales, (Chief Public Prosecutor of Superior and Criminal Prosecutorial Units) Víctor Cubas Villanueva, the primary reason for which human rights cases under investigation have been dismissed is because of insufficient information that would permit the identification of the alleged perpetrators. He argued that the lack of suffucient information is the direct result of the persistent refusal on the part of the armed forces and the Ministry of Defense to provide such information to investigators, or their assertion that such information does not exist.20In an effort to resolve this impasse, on two separate occasions commissions were formed consisting of representatives of the Public Ministry, the Ministry of Defense, and the Ombudsman’s Office, but no change in practice resulted.21

A series of reports published by the Ombudsman’s Office highlights that, in most cases, requests for information on the military or police personnel involved in allegations of human rights violations have not been received in a timely manner or judges have been informed “that…they do not have such information or files or that they have been burned or destroyed” (DEFENSORÍA DEL PUEBLO, 2004, p. 85). Similar claims are used frequently to deny access to information relating to human rights abuses despite several legal barriers to such behavior. This includes the 1972 Ley de Defensa, Conservación, e Incremento del Patrimonio Documental de la Nación (Law to Protect, Conserve, and Promote the Documentary Patrimony of the Nation), and the 1991 Ley de Sistema Nacional de Archivos (National System of Archives Law).22

The effects of this obstruction have been confirmed in numerous interviews with state prosecutors investigating human rights cases, principally in Lima and Ayacucho conducted by the lead author over the course of the past several years. Their inability to access information about who was stationed in what barracks, or to obtain specific information about military operations directives or orders, has seriously hindered the ability of prosecutors to identify alleged perpetrators and resulted in the dismissal of cases. In one interview, a government prosecutor showed the lead author a pile of fojas de servicio, or personnel files, of military personnel under investigation for human rights violations. During the Toledo administration, such forms were often provided to investigators who requested them, which allowed them to begin the painstaking task of trying to reconstruct chains of command, identify which military personnel participated in specific operations or were stationed at specific military bases, etc. However, from 2006 onward – coinciding with a general retreat in governmental support for criminal investigations into past human rights violations – even these documents were denied to investigators.

The 1984 case of 123 peasants murdered in Putis, in the Ayacucho region, helps to demonstrate the nature of obstructed access to information and its implications for the prosecution of grave human rights violations in Peru. Judges have been repeatedly informed that information on individuals who served in the army unit of interest does not exist: “no existe documentación alguna que permita identificar al personal militar que prestó servicios en la Base Militar de Putis.” (DEFENSORÍA DEL PUEBLO, 2008, p. 138).23 As a result – and despite the laborious collection of forensic evidence and testimony from witnesses and families (the Peruvian Forensic Anthropology Team recovered 92 bodies from clandestine graves in Putis) – this case was under preliminary investigation for more than ten years. Though the Public Ministry issued a formal indictment in this case in November 2011, a trial date has yet to be set. The accused are high-ranking military officers who are being charged as the intellectual authors of the crime; the material perpetrators remain unidentified. The Ministry of Defense continues to claim that no information exists about this case or those who may have participated in it. In 2009, then Defense Minister Rafael Rey Rey affirmed that both he and his predecessor, Antero Flores Aráoz, had actively searched for information about the Putis case but had found none; however, he never offered evidence of such a search, how it was conducted, nor any specific conclusions.24

Crucially however, in 2010, the Peruvian Army produced a document titled “In Honor of the Truth,” (En Honor a la Verdad) which among other things, included references to documents such as military studies and criteria for counter-subversive operations, annual military records, intelligence reports, and personnel files. In this report, the Standing Committee of Military History cites documents in the Central Archive of the Army such as annual reports, which show the operations and information about the army personnel who worked during that period, whose testimonies are part of the publication. Many of these documents are of the same types that have been requested repeatedly by investigators, human rights lawyers, judges, and prosecutors, and continue to be denied. The citation of such documentation belies repeated claims by the Ministry of Defense that information either did not exist, or had been lost or destroyed (ASOCIACIÓN PRO-DERECHOS HUMANOS, 2012).

Denials claiming non-existence of records are given repeatedly to requests for information from the Peruvian State. However, such responses do not comply with the State’s legal obligations to provide a comprehensive, independent investigation into any alleged destruction of records, to make its findings public, and to punish those responsible for unlawful destruction of records; to make concrete efforts to recover or reproduce relevant documents; and to provide a detailed account of the measures taken to do so.25

The Ombudsman’s Office has documented numerous other cases that have not progressed due to refusal on the part of military officials to provide information and that have not yet come to trial. For example, the disappearance of human rights activists Angel Escobar, which has been under investigation since October 2002, has yet to come to trial. Escobar was detained at a military base in Huancavelica, but no information has been provided to prosecutors about the identity of those stationed at the base; as a result the case has not moved forward (DEFENSORÍA DEL PUEBLO, 2008, p. 160). In the case of the 1990 massacre of 16 peasants in the Chumbivilcas, information requested about the military patrol on duty at the time of the massacre in the area has been denied by military officials; this case has been under investigation since February 2004 (DEFENSORÍA DEL PUEBLO, 2008, p. 156).

Another example illustrates an unfortunate pattern of the dismissal of ongoing cases of human rights violations due to the inability of prosecutors to access necessary information. In June 1988, five men were detained (in individual circumstances) and later found dead by their family members. The bodies showed signs of projectile lesions – gunshot wounds – that indicated execution style killings, that pointed to the involvement of operatives from the local military base at Churcampa. However, in March 2012, the investigators at the Public Ministry decided to dismiss the case, since the failure of the Ministry of Defense to provide information prevented them from determining the identities of the involved individuals (ASOCIACIÓN PRO-DERECHOS HUMANOS, 2012).

Where judges and prosecutors do receive responses to requests for information, responses are typically unsatisfactory. Such responses often refer to requests for communication documents and transcripts as well as procedural and historical documents pertaining to acts, rather than the identity of personnel (though as discussed above, the same excuses are often given for all denials). Many denials for information about specific individuals or patrols are justified by arguing that relevant records were destroyed “in compliance with regulation” (DEFENSORÍA DEL PUEBLO, 2005, p. 149). Beyond leading one to wonder what records indicate the documents in question were indeed destroyed (and why they are never provided), the Ombudsman’s Office has outlined the very regulatory framework that expressly prohibits the destruction of such records (DEFENSORÍA DEL PUEBLO, 2005, p. 149). Thus, it is clear that prosecutors must fight for every piece of information – whether it identifies key personnel in a case, is a statement on behalf of the accused, or clarifies activities carried out at by a particular individual or patrol – at all stages of the investigation and trial.

Arguments claiming that all documents were incinerated are demonstrably false. Lawyers and prosecutors have confirmed in interviews with the lead author that on numerous occasions, military officers on trial appear in court with military documents, including their personnel files. A judge explained that in one case she was investigating – the Chilliutira case, involving the 1991 extrajudicial execution of four people who were being transferred to a military base in Puno – the court requested the case file of the military inspector’s office, who had registered the crime in 1992. The military authorities refused to provide the files or names of those who were stationed at the base at that time, saying such information was not available. The judge noted, however, that the defendants in the case presented their service records, as part of their defense, to the court.26

The Peruvian Army itself has made reference to numerous documents that would be of value to investigators in its “In Honor of the Truth” report, including annual military reports, reports of specific military operations, and intelligence notes, among others. Such claims that all records have been destroyed reveal an underlying intention to obstruct access to information in cases of grave human rights violations. Interestingly, rather than citing the prerogative to classify information on national security grounds, the Ministry of Defense frequently argues that requested information does not exist or has been destroyed.

Finally, a further illustration of Peru’s obstruction of access to public information involves a legislative decree adopted in December 2012. Decree Law 1129 contains an article (article 12) denying public access to any information pertaining to national security and defense. This is a worrying development for several reasons. First, while the 2002 Transparency Law provides clauses for exempting certain information related to national security and defense, such exemptions are to be the exception to the rule. The 2012 Decree, however, establishes blanket confidentiality for information related to national security and defense, with no statute of limitations. In other words, secrecy is now the rule, and there are to be no exceptions to this rule.27

The second concern relates to the enforcement of secrecy on issues of national security and defense. According to the Press and Society Institute (Instituto Prensa y Sociedad), the decree establishes “an obligation of confidentiality on information that is secret under article 12, for any person who accesses this information through the exercise of his or her duties or position” (INSTITUTO PRENSA Y SOCIEDAD. 2012, emphasis added).28 In other words, since there is no indication that such “duties or position” be exercised in the service of the State, anyone, including journalists or civil society, could be charged with revealing national secrets in the exercise of their work. The punishment for such actions could entail up to 15 years in prison.

The norms contained in this troubling decree fly in the face of Peru’s commitment to the Inter-American Convention of Human Rights, jurisprudence from the Inter-American Court, and Peru’s own Constitution and Transparency Law, all of which mandate a posture of openness. The Inter-American Court has articulated the principle of “maximum disclosure,” which establishes a presumption that all information held by public authorities should be accessible, with only limited exceptions (INTER-AMERICAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS, 2006). Further, in the case of Mack Chang vs. Guatemala, the Inter-American Court ruled that in cases of grave human rights abuses, information cannot be withheld on the grounds of national security. Decree 1129 clearly violates the both the principle of maximum disclosure and non-exemption for cases of grave human rights abuse.

According to article 15 of Peru’s 2002 Transparency Law, decisions on whether to disclose information pertaining to defense or national security are to be made on a case by case basis and classified information are subject to a limited period (five years) – the assumption being that if information does not fit under specific guidelines allowing for secrecy, it is to be released. Now, instead of maintaining open access as a default (something Peru has surely struggled to achieve in the first place), the new decree establishes secrecy as the base-line, and eliminates exceptions. This new norm, combined with the threat of prosecution for journalists (and others) seeking access to certain information, clearly seeks to exempt the defense and security sectors from transparency, and provides a pointed illustration of the Peruvian State’s effort to obstruct access to information in cases of human rights abuse as well as in other arenas, such as military sector purchases.

While Peru’s Transparency Law has been on the books for a decade, the situation concerning access to information described in this article demonstrates that a “culture of transparency” the Law hoped to establish is far from a reality. And despite impressive progress on some fronts (i.e., the country’s return to democracy, restoration of free and fair elections, and the first-ever domestic prosecution of a democratically elected president for human rights violations), many government agencies and operations still function under a veil of secrecy.

In the case of successful prosecutions, it is important to note that official information is often obtained through other means than official channels. For instance, in the case of the investigations into the Colina Group, a military unit that was responsible for over 50 death-squad style killings during 1991 and 1992, the Armed Forces did not collaborate with the disclosure of documents, even when requested by prosecuting authorities.29 In response, in 2002, Judge Victoria Sanchez, following an anonymous tip about the location of documents pertaining to Colina Group activities, conducted an unannounced visit to the headquarters of the Comandancia General del Ejército and the offices of the National Intelligence Service and seized records she deemed essential to her investigation.30

Thanks to these documents, which included orders regarding the transfer of personnel, logistics and payments – as well as information provided by three mid-ranking military officials who participated in the Colina Group operations and who turned State’s evidence31 – the legal authorities were able to determine that the Colina Group was part of the formal military structure and that it depended functionally on the SIN; reconstruct its organizational structure; and document its operations over a two-year period. The extensive documentary evidence in this case was crucial in the convictions of several material and intellectual authors of the Barrios Altos massacre and the La Cantuta University disappearances, including, among others, former army chief General Nicolas Hermoza Rios, former spy chief Vladimiro Montesinos, former head of the SIN General Julio Salazar Monroe, and ultimately, former president Fujimori.32 (Notably, the Peruvian Army continued to deny the existence of the Colina Group even after these convictions were handed down.)

Such experiences are not likely to be replicated. They were highly contingent on a particular political moment, when a new transitional government was committed to investigating the misdeeds of the prior administration. Moreover, as Judge Sanchez noted, the minister of defense was a civilian and was supportive of her actions. In addition, at that historical moment, the military was weakened due to public displeasure over its close affiliation with the Fujimori government and credible allegations of widespread corruption. In some ways, the Armed Forces has found a new motive to regroup and reassert its institutional identity, in order to protect its understanding of itself as the “savior” of the Peruvian nation in the face of the terrorist threat, and to protect certain officials who are currently charged with human rights crimes. Indeed, since 2002, no similar action attempting to seize documentary evidence has been undertaken. Much more commonly, judges request information in the context of ongoing investigations, but interviews by the lead author with judges adjudicating these cases confirms that this information is often not provided, or is not provided in its entirety.

Most importantly, the ability of investigators, judges, and the public to access information suffers from a lack of institutional centralization and enforceability. In this area, Peru could learn from the Mexican FOI system, which was enacted in 2002. Mexico has developed two important advantages in its system. First, the legislation created a streamlined, centralized interface – Infomex.org – where citizens and groups can request information and make appeals to the relevant agencies. Second, the Federal Institute for Access to Information (IFAI, which manages Infomex.org) is an independent agency within the federal public administration that serves to resolve appeals; train public servants and civil society on FOI; monitor compliance; and promote and instruct citizens and groups on how to access information.

IFAI has a good track record for responding to inquiries and appeals to initial denials. IFAI staff and commissioners are generally accessible and seen as committed to fostering an atmosphere of transparency (SOBEL et al., 2006). The institution’s design and budget process vis-à-vis the executive and legislative branches of the government allow for a high degree of autonomy. IFAI also trains public servants on the FOI legislation and regulations for transparency; how to preemptively offer access to information; and how to respond to requests made by citizens and civil society. Additionally, IFAI adjudicates agency denials to provide information and is responsible for ensuring that information covered by the legislation is provided by the responsible agency.

IFAI does not have the ability to enforce its orders of transparency, though it has managed to get agencies to provide the requested information in most cases (SOBEL et al., 2006). Requests for information whose release IFAI cannot compel must refer cases of non-compliance to the Ministry. As of 2005, only five cases had been so referred (OPEN SOCIETY JUSTICE INITIATIVE, 2006). A similar institution in Peru could go a long way in creating a culture of transparency and a default mode of government organs rendering access to public information.

However, even an independent and capable institution along the lines of Mexico’s IFAI would have trouble overcoming the greatest obstacle that has faced access to information in human rights cases in Peru – that of a lack of political will. The challenges to public access to information, as illustrated in this article, are numerous. In addition to obstruction at various levels of government, in key agencies that hold important information from judges and prosecutors, access to information in Peru is hamstrung by a myriad of bureaucratic and budgetary restraints. Nevertheless, the fundamental challenge resisting the establishment of a culture of transparency broadly, and the use of important government information in human rights cases specifically, relates to political will. In a comparative study on the obstacles to implementing freedom of information schemes in Latin America, the Centro de Archivo y Accesso a la Información Pública(CAinfo) noted that while “a good part of the political authorities and public officials in Peru consider transparency a simple part of their duties and not a charge or a bother […] the implementation of a professional system of archiving is hindered by […] an atmosphere culturally resistant to this institution within military and police sectors” (CAinfo, 2011, p. 55).

While it is beyond the scope of this paper to examine in full the political dynamics at play, it is important to note that with the 2006 election of Alan Garcia to a second presidential term, an alliance was forged between Garcia, his close associates, and sectors of the armed forces who had a mutual interest in guaranteeing impunity for human rights violations. Massive human rights abuses occurred during Garcia’s first government (1985-1990) and it is not inconceivable that he might one day be held to account for innumerable crimes, such as the 1986 Fronton massacre, the 1988 Cayara massacre, or the string of assassinations of opposition leaders during the late 1980s at the hands of the Comando Rodrigo Franco, a paramilitary group that allegedly operated within the Ministry of the Interior and under the auspices of his close political associate, then Interior Minister, Agustin Mantilla.33 (Members of the APRA party are also alleged to have particpated in these operations.) In the 2006 presidential race, Garcia chose as his vice-president retired Navy Admiral Luis Giampetri, who led the efforts to restore government control over the Fronton prison in 1986. Giampetri was a forceful advocate for the military during his term in the vice-presidential office. During the Garcia government, the State established a policy to pay for the defense of military officials accused in human rights violations cases, though oftentimes victims lack representation, putting them at a serious disadvantage.

Additionally, several efforts were made during the García administration to prevent future human rights prosecutions. In 2008, two bills were put forth that would have granted amnesty for State agents accused of human rights violations, though neither passed. In 2010, a presidential decree law (D.L. 1097) was passed which amounted to a blanket amnesty, but it was met with massive domestic and international opposition and was eventually revoked. However, government representatives, from the Executive to the Minister of Defense, frequently and vociferously attacked human rights organizations representing victims in these cases, and charged them as well as judges and prosecutors of engaging in “political persecution” of the armed forces. In such a climate, it is evident that larger forces are at play that undermine the efforts of victims, lawyers, prosecutors, and judges to gain access to public information about past human rights violations.

While the public discourse on these issues has mitigated in tone since the election of Ollanta Humala as president, his own standing as a former military official who once faced charges of human rights violations (charges were dropped after witnesses withdrew their testimony) has led to a great deal of speculation about what one could expect under his administration. On the one hand, his government has vigorously embraced initiatives such as the Open Government Initiative, which is viewed positively by right to information advocates, but at the same time, decree laws such as 1129, discussed above, reveal that old habits die hard. The culture of secrecy that underlies impunity in Peru and elsewhere in the region remains an enduring challenge for right to information and for the broader set of rights that this right is meant to facilitate, including right to truth and right to justice.

1. This paper focuses on human rights violations committed by State actors, which according to the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission, constitute approximately 37 percent of the total fatalities during the 20-year internal armed conflict. Prosecutions of members of the two armed insurgent groups, Shining Path and MRTA, are not subject to the same kind of demands regarding access to official information since the perpetrators are non-state actors. Hundreds of Shining Path and MRTA members, including the top leadership of both organization, have been prosecuted and are currently serving prison sentences of varying duration. The leadership received sentences of life imprisonment.

2. This project, which developed alongside and with input from similar projects in Argentina and Chile, is further elaborated in: COLLINS; BALARDINI; BURT, 2013.

3. Reports of trial observations can be viewed on project website, Human Rights Trials in Peru Project, at www.rightsperu.net under “Blog/Analysis”.

4. Colombia was the first enactor of FOI legislation in Latin America in 1985.

5. Note: Bolivia and Argentina enacted executive decrees relating to access to information in 2005 and 2003, respectively, but have no legislative or constitutional codification.

6. The court ruled that the state’s denial violated the victims’ rights to freedom of expression under article 13 of the American Convention on Human Rights, to which Chile is a signatory.

7. Available at: http://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/litigation/claude-reyes-v-chile. Last accessed on: May. 2013.

8. Available at: http://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/litigation/gomes-lund-v-brazil. Last accessed on: May. 2013

9. Available at: http://www.cverdad.org.pe/ingles/ifinal/index.php. Last accessed on: May. 2013.

10. Cf. Banisar (2006). Available at: freedominfo.org/regions/latin-america/peru/. Last accessed on: May. 2013.

11. “No information related to violations of human rights or of the Geneva Conventions of 1949 shall be considered classified, in any circumstance, by any person.” (PERÚ, 2003).

12. Nota de Prensa No.012/2013/DP/OCII, “Organizaciones de la sociedad civil apoyan la creación de una institución garante en materia de transparencia y acceso a la información pública,” Lima, 29 de enero de 2013. Available at: http://www.larepublica.pe/29-01-2013/apoyan-creacion-de-una-institucion-garante-en-materia-de-transparencia-y-acceso-la-informacion-publi. Last accessed on: 01 Mar. 2013.

13. This section draws on a previously published article (BURT, 2009).

14. The affirmation by these courts that forced disappearance constitutes a crime against humanity is of critical importance in Peru’s efforts to prosecute human rights cases. The majority of human rights violations, including extrajudicial executions, the forced disappearance of an estimated 15,000 Peruvian citizens, and the widespread use of torture and sexual violence, occurred 25 to 30 years ago, during the peak years of violence in 1983 and 1984, and again between 1987 and 1990, when Peru held the dubitable distinction of having the world record of forced disappearances according to the United Nations Working Group on Forced Disappearances. Defendants have sought to have charges against them dismissed, asserting that the statute of limitation applies in cases that occurred 25 or 30 years ago.

15. Of these 20 guilty verdicts, in nine, all defendants were convicted, while in eleven, at least one defendant was convicted and at least one was acquitted.

16. We refer to sentences since there have been rulings in some human rights cases more than once, either because different defendants were tried separately, or because retrials have been ordered by the Supreme Court. A total of only 38 human rights cases have received sentences. A full listing can be viewed on the Human Rights Trials in Peru Project website: Available at: http://rightsperu.net/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&layout=blog&id=40&Itemid=58. Last accessed on: May. 2013.

17. Data compiled by author for Peru Human Rights Trials Project Database. Data up to date as of March 1, 2013.

18. These arguments are more fully developed in: BURT 2014 (forthcoming).

19. In the Defensoría’s most recent report in 2008, of the 339 accused facing trial, 264 and 47 hailed from the Army and the National Police, respectively. Data culled from ongoing research have identified over 650 former or actual members of the State security forces under investigation for human rights violations.

20. Lead author interview, Víctor Cubas Villanueva, Fiscal Superior Coordinador de las Fiscalías Penales Supraprovinciales, Ministerio Público, Lima, July 2010.

21. To our knowledge, no public record of the existence of these commissions exists. This information was obtained through interviews by the lead author with functionaries at the Defensoría del Pueblo and human rights organizations who have knowledge of the commissions. A copy of one of the commission’s reports is on file with the lead author.

22. Available at: http://www.datosperu.org/tb-normas-legales-oficiales-2008-Mayo-21-05-2008-pagina-37.php and http://www.datosperu.org/tb-normas-legales-oficiales-2000-Marzo-30-03-2000-pagina-35.php. Last accessed on: May. 2013.

23. “There exists no documentation that permits identification of military personnel who served at the Putis military base.” (DEFENSORÍA DEL PUEBLO, 2008, p. 138).

24. Affirmation of Defense Minister Rafael Rey Rey in response to the Putis case. Radio Programas del Perú (RPP), 28 de setiembre de 2009, http://www.rpp.com.pe/2009-09-28-rafael-rey-los-militares-no-tienen-una-proteccion-adecuada-noticia_211882.html. Last accessed on: May 2013.

25. In Claude Reyes v. Chile, the Inter-American Court reaffirmed that the right of access to State-held information has both an individual and a collective dimension, and imposes duties on the State: “[Article 13] protects the right of the individual to receive [State-held] information and the positive obligation of the State to provide it. … The delivery of information to an individual can, in turn, permit it to circulate in society, so that the latter can become acquainted with it, have access to it, and assess it….” (INTER-AMERICAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS, 2006. Series C No. 151, para. 77).

26. Lead author interview, Judge Victoria Sanchez, Sala Penal Nacional, January 18, 2013.

27. The Ombudsman’s Office filed a legal petition challenging the constitutionality of article 12 of Decree Law 1129. Personal communication between lead author and Fernando Castañeda of the Ombudsman’s Office, 9 April 2013.

28. Instituto Prensa y Sociedad. Communiqué, December 10, 2012. Available at: http://www.ipys.org/comunicado/1478. Last accessed on: May. 2013.

29. “Ejército no apoyó investigación a Colina”. La República, October 7, 2008.

30. Lead author interview, Judge Victoria Sanchez, Sala Penal Nacional, January 18, 2013.

31. One of the collaborators in the Colina Group case had been in charge of logistics; he provided telephone surveillance records; receipts and expenditure records; and other documents. Interview with lead author, Judge Victoria Sanchez, Sala Penal Nacional, January 19, 2013.

32. For reasons that remain unclear, as of this writing the case against Montesinos and Hermoza Ríos in the case of the La Cantuta disappearances has not moved to oral trial phase. Both were convicted in 2010 as the intellectual authors of the Barrios Altos massacre, the disappearance of nine peasants from Santa, and the murder of journalist Pedro Yauri. The conviction was upheld on appeal in 2013.

33. This case moved to public trial in 2013. A formal indictment has been issued in the case of El Frontón but as of this writing it has not yet moved to public trial.

Bibliography and other sources

ACKERMAN, John; SANDOVAL-BALLESTEROS, Irma. 2006. The global explosion of freedom of information laws. Administrative Law Review, v. 58, no. 1, p. 85-130, winter 2006.

AMBOS, Kai. 2011. The Fujimori Judgment. Journal of International Criminal Justice, v. 9, no. 1, p. 137-158, Mar.

ASOCIACIÓN PRO-DERECHOS HUMANOS (APRODEH). 2012. Access to information in the investigation of Cases of Grave Human Rights Violations in Peru. Audience of the 144th Period of Ordinary Sessions, Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. 2012. 26 Mar.

BANISAR, David. 2006. Freedom of Information and Access to Government Record Laws around the World, 30 November. Available at: http://freedominfo.org/regions/latin-america/peru/. Last accessed on: 01 Mar. 2013.

BURT, Jo-Marie. 2009. Guilty as charged: the trial of former President Alberto Fujimori for grave violations of rights human. International Journal of Transitional Justice, v. 3, n. 3, p. 384-405.

_______. 2014 (forthcoming). “Rethinking Transitional Justice: The Paradoxes of Accountability Efforts in Postwar Peru.” In Embracing Paradox: Human Rights in the Global Age, Edited by Steven J. Stern and Scott Strauss (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press).

CENTRO DE ARCHIVOS Y ACCESO A LA INFORMACIÓN PÚBLICA (CAinfo). 2011. Venciendo la cultura de secreto: obstáculos en la implementación de políticas y normas de acceso a la información pública en siete países de América Latina. Montevideo, Uruguay. Available at:www.adc.org.ar/download.php?fileId=630. Last accessed on: 01 Mar. 2013.

COLLINS, Cath, BALARDINI, Lorena; BURT, Jo-Marie. 2013. Mapping perpetrator prosecutions in Latin America. International Journal of Transitional Justice, v. 7, n. 1, p. 8-28.

DEFENSORÍA DEL PUEBLO (PERÚ). 2004. A un año de la Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación. Informe Defensorial n. 86. Lima, Perú: Defensoría del Pueblo, 2004.

______. 2005. A dos años de la Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación. Informe Defensorial n. 97. Lima, Perú: Defensoría del Pueblo, 2005.

______. 2006. El difícil camino de la reconciliación: justicia y reparación para las víctimas de la violencia. Informe Defensorial n. 112. Lima, Perú: Defensoría del Pueblo, 2006.

______. 2007. El Estado frente a las víctimas de la violencia: ¿Hacia dónde vamos en políticas de reparación y justicia? Informe Defensorial n. 128. Lima, Perú: Defensoría del Pueblo, 2007.

______. 2008. A cinco años de los procesos de raparación y justicia en el Perú: balance y desafíos de una tarea pendiente. Informe Defensorial n. 139. Lima, Perú: Defensoría del Pueblo, 2008.

______. 2011. La actuación del Poder Judicial en el marco del proceso de judicialización de graves violaciones a derechos humanos. Informe de Adjuntía no. 004-2011-DP/ADHPD. Lima, Perú: Defensoría del Pueblo, 2011.

INTER-AMERICAN DIALOGUE. 2004. Access to Information in the Americas: a Project of the Inter-American Dialogue, Conference Report. Available at: http://www.thedialogue.org/PublicationFiles/Access%20Report.pdf. Last accessed on: 01 Mar. 2013.

INSTITUTO PRENSA Y SOCIEDAD. 2012. Communiqué, December 10. Available at: http://www.ipys.org/comunicado/1478. Last accessed on: 01 Mar. 2013.

LA REPÚBLICA. 2008. Ejército no apoyó investigación a Colina. Lima, Perú, 07 oct. 2008. Available at: http://www.larepublica.pe/07-10-2008/ejercito-no-apoyo-investigacion-colina. Last accessed on: 10 Mar. 2013.

MENDEL, Toby. 2008. Freedom of Information: a comparative legal survey. United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. Available at: http://portal.unesco.org/ci/en/files/26159/12054862803freedom_information_en.pdf/freedom_information_en.pdf. Last accessed on: 01 Mar. 2013.

_______. 2009. Right to information in Latin America: a comparative legal survey. United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Available at: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/communication-and-information/resources/publications-and-communication-materials/publications/full-list/the-right-to-information-in-latin-america-a-comparative-legal-survey/. Last accessed on: 01 Mar. 2013.

MICHENER, Robert Gregory. 2010. The surrender of secrecy: explaining the emergence of strong access to public information laws in Latin America. Thesis (PhD) – University of Texas at Austin University of Texas at Austin (UTexas), United States. Available at: http://gregmichener.com/Dissertation.html. Last accessed on: 01 Mar. 2013.

OPEN SOCIETY FOUDATIONS. 2006. Transparency and silence: a survey of access to information laws and practices in 14 countries. Available at: http://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/sites/default/files/transparency_20060928.pdf. Last accessed on: 01 Mar. 2013.

______. 2009. Litigation Claude Reyes v. Chile. Democracy Demands “Maximum Disclosure” of Information. 20 April. Available at: http://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/litigation/claude-reyes-v-chile. Last accessed on: 01 Mar. 2013.

_______. 2010. Litigation Gomes Lund v. Brazil. Brazil Fails to Prevent Impunity, Guarantee Right to Truth and Information. 1 December. Available at: http://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/litigation/gomes-lund-v-brazil. Last accessed on: 01 Mar. 2013.

OPEN SOCIETY JUSTICE INITIATIVE. 2006. Transparency and silence: a survey of access to information laws and practices in 14 countries. Available at: http://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/sites/default/files/transparency_20060928.pdf. Last accessed on: 01 Mar. 2013.

PERÚ. 1972. Decreto Ley Nº 19414. Ley de Defensa, Conservación e Incremento del Patrimonio Documental de la Nación. 16 de mayo. Available at: http://www.datosperu.org/tb-normas-legales-oficiales-2008-Mayo-21-05-2008-pagina-37.php. Last accessed on: 01 Mar. 2013.

_______. 1991. Ley Nº 25323, Ley del Sistema Nacional de Archivos. 11 de jun. Available at: http://www.datosperu.org/tb-normas-legales-oficiales-2000-Marzo-30-03-2000-pagina-35.php. Last accessed on: 01 Mar. 2013.

_______. Constitución [1993]. 2005. Constitución Política del Perú 1993 con reformas hasta 2005 = Political Constitution of Peru 1993 with reforms until 2005. Available at: http://pdba.georgetown.edu/Constitutions/Peru/per93reforms05.html#titIcapI. Last accessed on: 01 Mar. 2013.

_______. 2003. Ley Nº 27806. Ley de transparencia y acceso a la información pública. El Peruano, Normas legales, p. 249373-4, Lima, jueves 7 de ago. Available at: http://www.peru.gob.pe/normas/docs/LEY_27806.pdf. Last accessed on: 01 Mar. 2013.

_______. 2010. Decreto Ley Nº 1097. Regula la aplicación de normas procesales por delitos que implican violación de derechos humanos. El Peruano, Normas e Reglamentos, Lima, p. 424816-17. Available at: http://www.congreso.gob.pe/ntley/Imagenes/DecretosLegislativos/01097.pdf. Last accessed on: 01 Mar. 2013

________. 2011. Ministry of Defense. Resolución Ministerial 392-2011 DE/SG del 28. Directiva General MN-008-2011MDSG-UAIP. Procedimientos para el acceso, clasificación, reclasificación, desclasificación, Archivo y conservación de la información del sector defensa. April 2011.

______. 2013. Decreto Ley Nº 1129. Regula el Sistema de Defensa Nacional. El Peruano, Normas e Reglamentos, Lima, p. 492103-4, jueves 4 de abril. Available at: http://spij.minjus.gob.pe/CLP/contenidos.dll/CLPlegcargen/coleccion00000.htm/tomo00402.htm/a%C3%B1o360760.htm/mes382638.htm/dia382977.htm/sector382982/sumilla382985.htm?f=templates$fn=document-frame.htm$3.0#JD_DLEG1129. Last accessed on: 01 Mar. 2013.

PERUVIAN TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION. 2003. Final report. Available at: http://www.cverdad.org.pe/ingles/ifinal/index.php. Last accessed on: 01 Mar. 2013.

RIVERA PAZ, Carlos. 2009. Los jefes no son responsables: Sala Penal Nacional emite vergonzosa sentencia en caso “Los Laureles”. Revista Ideéle, Lima, Perú, n. 199. Available at: http://www.revistaideele.com/archivo/node/553. Last accessed on: 01 Mar. 2013.

______. 2012. La sentencia del caso Barrios Altos: el nuevo instrumento de la impunidad, Lima, July 23. Available at: http://carlosrivera.lamula.pe/2012/07/23/la-sentencia-del-caso-barrios-altos-el-nuevo-instrumento-de-la-impunidad/carlosrivera. Last accessed on: 01 Mar. 2013.

ROBERTS, Alasdair. 2001. Structural pluralism and the right to information. University of Toronto Law Journal, v. 51, n. 3, p. 243-271.

SOBEL, David L. et al. 2006. The Federal Institute for Access to Information in Mexico and a Culture of Transparency. Project for Global Communication Studies at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania. A report for the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. Philadelphia, PA: Annbenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania.

THE GLOBAL NETWORK OF FREEDOM OF INFORMATION ADVOCATES. 2011. President Rousseff Signs Access to Information Law. 21 November. Available at: http://www.freedominfo.org/2011/11/president-rousseff-signs-access-to-information-law/. Last accessed on: 01 Mar. 2013.

TORRES, Natalia. 2011. El Salvador joins the list of FOI countries. 11 Mar. 2011. Available at: http://www.freedominfo.org/2011/03/el-salvador-joins-the-list-of-foi-countries/. Last accessed on: 01 Mar. 2013.

Jurisprudence

INTER-AMERICAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS (IACHR). 2003. Case of Mack Chang v. Guatemala, Judgement of November 25.

_______. 2006. Case of Claude Reyes v. Chile, Judgment of September 19.

_______. 2010. Case of Gomes Lund v. Brazil (Guerrilha do Araguaia), Judgement of November 24.