The role and impact of online activism for feminisms in Brazil

For social movements, the internet has become a powerful tool. Feminisms have been appropriating it since the 1990s, which is when they began formulating a cyberfeminism that affirmed the exceptional nature of the digital world. Changes over the past 20 years have made the internet part of our lives and our lives are part of the internet. Today, the world wide web is a medium for feminist media. It is the stage for online mobilisations via hashtags and organising street protests. And it is the infrastructure for the formulation of new ideas and the production of a feminist counterpublic that challenges the discourse of the dominant public sphere. Through the internet, feminists have revitalised the debate, revamped practices and succeeded in forcing mainstream media to pay attention to their demands. Based on an analysis of shares on Facebook during the week of International Women’s Day in 2018 in Brazil, we present an overview of the reach and the clash between discourses and counter discourses. Our findings point the way to an agenda for research and actions, which involves everything from how platforms function to policies on digital security and access to the internet and knowledge.

There is nothing new in the fact that the internet is central to social mobilisations today. It would also appear that one only has to have been on the internet, and paid attention, for close to a decade to notice that agendas related to racial, sexual and gender minorities and their voices have found new and broader spaces for their expression and dissemination.

Furthermore, it no longer makes sense to talk about a “virtual world” or “cyberspace”, as opposed to a “real world”, like it once did.11. The reference to cyberspace used to be very popular, starting with the works of influential theorists such as Pierre Lévy. In a series of books, Lévy described and analysed “cyberspace” as an element that introduced communication ‘for everyone with everyone’ and that would lead to the emergence of a collective intelligence thanks to the use of a series of intellectual tools, devices and technologies. He also developed the “virtual” concept based on the works of Gilles Deleuze. See Pierre Lévy, O que É o Virtual? (São Paulo: Editora 34, 2004); Pierre Lévy, Inteligência Coletiva: Para uma Antropologia do Ciberespaço (São Paulo: Loyola, 2009); Pierre Lévy, Cibercultura (São Paulo: Editora 34, 2011). With the advances of digital technology in different aspects of our lives and the constant use of instant online forms of communication that many people do not even associate with the internet, these stagnant divisions do not reflect the way people experience and appropriate technology. This also goes for activism and social movements for which there is a strong connection between their online and offline forms of action. Brazilian feminisms are an excellent example for understanding the paradoxes involved in the use of the internet for social mobilisation in the late 2010s, due to their vastness and diversity.

Feminists’ struggle to influence and define the agenda of the media and communication processes is also nothing new. Since at least the second wave,22. The division of the feminist movement into “waves” is common in the literature on this subject. The “second wave” in Brazil is said to have begun in the 1970s. Its predecessor was the period that went from the end of the 19th century to the 1930s during which Brazilian women won, for example, the right to vote and organise themselves to obtain better working conditions (Fabíola Fanti, “Mobilização Social e Luta por Direitos: Um Estudo Sobre o Movimento Feminista,” PhD thesis (Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas, 2016). the movement’s organising process has involved reflecting critically on the media and developing alternative media channels to disseminate information on certain issues and give voice to the marginalised. In Brazil, since the 1970s, newspapers such as Brasil Mulher (1975-1979), Nós Mulheres (1976-1978) and Mulherio (1981-1987) have played this role.33. Tainan Pauli Tomazetti and Liliane Dutra Brignol, “O Feminismo Contemporâneo a (Re)configuração de um Terreno Comunicativo para as Políticas de Gênero na Era Digital” (Anais da Alcar, UFRGS, Porto Alegre, RS, 2015); even though our article does not address this specific topic, it is important to highlight that historically, the concern with the elaboration of their own narratives about themselves has been central for black activism. This can be seen, for example, in the movement’s intense effort to produce newspapers since the late 19th century (Natália Neris, “A Tradição de se Expressar: As Letras e as Lutas de Negras e Negros nos Meios de Comunicação no Brasil,” in Desafios à Liberdade de Expressão no Século XXI, Artigo 19 (2018): 20-23). The same holds for LGBT activism, especially since the era of the military regime (Flavia Peret, Imprensa Gay no Brasil entre Militância e Consumo - São Paulo: Publifolha, 2012). The internet reinforced these practices, yet via its own physical structure and logic, which allow for communication of “everyone with everyone” – in the highest form of what Castells calls “mass self-communication”.44. Manuel Castells, A Galáxia da Internet: Reflexões Sobre a Internet, os Negócios e a Sociedade (Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 2003). Sending messages via the web is decentralised and reception is fragmented. In addition to its use as “feminist media”, the internet and the web applications designed for it have permitted the creation of new formats for interaction: meetings, exchanges and connections take place regardless of people’s geographic location among individuals who share the same interests, but who may never meet in person. In fact, the internet has made transnational exchanges possible. This has had impacts on the transnationalisation of feminism, which Nancy Fraser claims is characteristic of a “third wave”.55. “Today, accordingly, feminist claims for redistribution and recognition are linked increasingly to struggles to change the frame. Faced with transnationalised production, many feminists eschew the assumption of national economies. In Europe, for example, feminists target the economic policies and structures of the European Union, while feminist currents among the anti-World Trade Organization protestors are challenging the governance structures of the global economy. Analogously, feminist struggles for recognition increasingly look beyond the territorial state. Under the umbrella slogan, “women’s rights are human rights”, feminists throughout the world are linking struggles against local patriarchal practices to campaigns to reform international law” (Nancy Fraser, “Mapeando a Imaginação Feminista: Da Redistribuição ao Reconhecimento e à Representação,” Revista Estudos Feministas 15, no. 2 - 2007). In spaces built on affinities, such as Facebook groups created to discuss feminist issues, challenges to the hegemonic meanings of gender identities and sexualities multiply and become fragmented. This reflects, but also affects, the intensity of social changes we are currently experiencing: in the realm of multilateral communications, the possibilities of encountering new meanings for the world are infinite.66. Fabiana Poços Biondo, “Liberte-se dos Rótulos: Questões de Gênero e Sexualidade em Práticas de Letramento em Comunidades Ativistas do Facebook,” RBLA 15, no. 1 (2015).

Feminist mobilisations via the internet began in the 1990s under the umbrella of cyber-feminism – a set of intellectual and artistic products influenced by Donna Haraway’s metaphor of the cyborg.77. Donna Haraway, “A Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the 1980s,” Socialist Review 80 (1985): 65-108. These works were linked to the digital culture and have been said to be, a posteriori, excessively optimist: the internet was, in itself, believed to have enormous potential for the liberation of women.88. Judy Wajcman, “Feminist Theories of Technology,” Cambridge Journal of Economics 34, no. 1 (2010): 143-152. From the 2000s on, the relationship between feminism and the internet became more diversified and complex,99. Carolina Branco de Castro Ferreira, “Feminismos Web: Linhas de Ação e Maneiras de Atuação no Debate Feminista Contemporâneo,” Cadernos Pagu, no. 44 (2015). as it incorporated discussions on intersectionality, women’s participation in technological development1010. See, for example: Judy Wajcman, “Reflections on Gender and Technology: In What State is the Art?,” Social Studies of Science 30, no. 3 (2000): 447-64; Graciela Selaimen, “Mulheres Desenvolvedoras de Tecnologias - O Desafio das Histórias Invisíveis que Moram entre Zeros e Uns,” in Internet em Código Feminino, Graciela Natahnson (Buenos Aires: La Crujía Ediciones, 2013). (including digital) and the extension of discrimination and violence to women’s lives online.

Twenty years later, the internet has become an important element for a broad range of feminist coalitions and generated major debate. Furthermore, the connections between digital networks and the street is central for understanding the state of the feminist movement in Brazil and, we dare say, perhaps everywhere else. Based on a database built to register feminist protests in the country from 2003 to 2017, which has over 400 entries, Medeiros and Fanti identified nothing less than a “return to the streets” in 2011 with the emergence of the SlutWalk.1111. It is not that there were no street demonstrations in the previous period. There were protests, but they were different in nature: their numbers were low and the large majority of them were organised by the Workers’ Party (PT), which is usually called “campo democrático-popular” (Jonas Marcondes Sarubi de Medeiros and Fabíola Fanti, “A Gênese da “Primavera Feminista” no Brasil: A Emergência de Novos Sujeitos Coletivos,” - project presented to the Esfera Pública e Cultura Política do Núcleo Direito e Democracia do CEBRAP subgroup, 2018). This movement was born in Toronto, Canada when, in the midst of attacks on women at a university campus, a police officer stated that to prevent violence, women should stop dressing like sluts. In April 2011, a protest was held to defend women’s autonomy over their bodies and sexuality. The movement rapidly spread around the world, with SlutWalks being organised everywhere, including Brazil. The use of the internet and social media was key in the organisation, mobilisation and dissemination of information on these protests. It was always closely linked to physical spaces: the marches were organised locally in each city, involved the occupation of public space and used the body as territories of political expression.1212. Ibid. It is no surprise that SlutWalk is being broadly studied and serves as the reference for many feminisms today.1313. For example: Raquel Costa Goldfarb, “Sim, Eu Sou Vadia: Uma Etnografia do Coletivo Marcha das Vadias na Paraíba,” PhD thesis (presented in the area of gender studies at DINTER - UFSC, IFPB, IFPE, IFAL, 2014); Carla de Castro Gomes, “Corpo e Identidade no Movimento Feminista Brasileiro Contemporâneo: O Caso da Marcha das Vadias” (Anais do 40o Encontro Anual da Anpocs, Caxambu, MG, 2016); Camila Carolina Hildebrand Galetti, “Corpo e Feminismo: A Marcha das Vadias de Campinas/SP,” master’s thesis (Departamento de Sociologia da Universidade de Brasília/UnB, 2016); Tainan Pauli Tomazetti, “Movimentos Sociais em Rede: A Marcha das Vadias - SM e a Experiência do Feminismo em Redes de Comunicação,” master’s thesis (Graduate Programme in Communications at the Universidade Federal de Santa Maria - UFSM, RS, 2015); Laís Modelli Rodrigues and Caroline Kraus Luvizotto, “Feminismo na Internet: O Caso do Coletivo Marcha das Vadias e Sua Página no Facebook,” Colloquium Humanarium 11, special edition (July-December 2014).

These mobilisations are highly publicised and covered by mainstream media. There are also blogs and social media pages fulfilling the function of feminist media that are also the object of research and analysis. Examples include Blogueiras Feministas (Feminist Bloggers),1414. Laís Modelli Rodrigues, “Blogs Coletivos Feministas: Um Estudo Sobre o Feminismo Brasileiro na Era das Redes Sociais na Internet,” master’s thesis (Graduate Programme in Communications at the Faculdade de Arquitetura, Artes e Comunicação, Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho”, 2016); Ferreira, “Feminismos Web,” 2015. o Lugar de Mulher (A Woman’s Place),1515. Daniele Ferreira Seridório, Douglas Alves Graciano, Eduardo Magalhães, Guilherme Henrique Vicente and Josiane de Cássia Lopes, “Movimento Feminista em Rede: Análise do Blog e do Facebook ‘Lugar de Mulher’,” Pensamento Plural, no. 17 (2015). the Feminismo Sem Demagogia (Feminism without Demagogy) Facebook page and Moça, Você é Machista (Girl, You’re Sexist).1616. Nícia de Oliveira Santos and Jordana Fonseca Barros, “O Movimento Feminista no Facebook: Uma Análise das Páginas Moça, Você é Machista e Feminismo sem Demagogia - Original” (work presented at the Simpósio Internacional de Tecnologia e Narrativas Digitais, UFMA, São Luís, MA, 2015). But the internet has also played a role in a less visible kind of social organising. For example, Medeiros1717. Jonas Marcondes Sarubi de Medeiros, “Microssociologia de Uma Esfera Pública Virtual: A Formação de Uma Rede Feminista Periférica na Internet” (Seminário FESPSP Cidades Conectadas: Os Desafios Sociais na Era das Redes, São Paulo, SP, 2016). conducted an ethnographic study that shows that social media was key for the founding of feminist groups in the outskirts of the city of São Paulo, and sometimes fulfils the crucial task of enabling people to overcome geographic limitations. The group of women graffiti artists, the M.A.N.A Crew (Mulher Atitude Negritude e Arte, or Women Attitude Negritude and Art) was started when two of its leaders met on Instagram. One lived in the Ermelino Matarrazo district and the other, in Cidade Tiradentes – areas located in the periphery of São Paulo, nearly 20 km from one another. Also, even though the planning of the First National March of Black Women held in Brasilia in 2015 was done during an in-person meeting, it was through their communication on social media that the organisers and other women activists mobilised activists from all over the country.1818. Renata Barreto Malta and Laís Thaíse Batista Oliveira, “Enegrecendo as Redes: O Ativismo de Mulheres Negras no Espaço Virtual,” Gênero 16, no. 2 (2016): 66.

As we stated above, in addition to serving as a medium for feminist media and its usefulness for the coordination of meetings and actions that take place offline, social media itself is a space for activism and debate1919. Castells, A Galáxia da Internet, 2003. and these interactions have renewed practices and discourses. Lawrence and Ringrose2020. Emilie Lawrence and Jessica Ringrose, “From Misandry Memes to Manspreading: How Social Media Feminism is Challenging Sexism” (A Collaborative Critical Sexology and Sex-Gen-in-the-South seminar, Critical Sexology, United Kingdom, 2016). observed, for example, the development of a culture of denunciation that is particular to social media: by weaving connections and raising voices that previously did not have a media structure to amplify them (due to media concentration and the practice of broadcasting a very limited range of voices), women can quickly expose sexism and misogyny in culture and behaviour and react to violence and male domination. One of the popular forms of this kind of mobilisation are campaigns that use hashtags to organise reporting: in Brazil, this was the case of the #MeuPrimeiroAssédio (#MyFirstHarassment), #MeuAmigoSecreto (#MySecretFriend), #EuNãoMereçoSerEstuprada (#IDoNotDeserveToBeRaped), and #NãoPoetizeOMachismo (#Don’tPoeticiseSexism) campaigns.2121. In her research, Malcher (2016) focussed on this issue and identifies a paradoxical aspect of the debate: by transmitting simplified messages, hashtag campaigns have the power to reach individuals who do not identify with “traditional” feminist ideas, but they also reduce the struggle, as they reduce the complexity of the problems addressed. One example of this type of campaign was the one that used the #EuNãoMereçoSerEstuprada (#IdoNotDeserveToBeRaped) hashtag. It was launched in response to a study by IPEA (Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada) that revealed that 65 per cent of Brazilians agreed with the statement that a woman who shows her body deserves to be attacked. Starting with a photo posted by activist Nana Queiroz, thousands of women (including celebrities) began sharing photos of themselves with a sentence written on their body or on a sign, or only the hashtag in the attempt to address mainstream media. The paradox is that while the simplicity of the message makes it easier for different groups to adopt it, it also means that it can be rapidly voided of meaning: when IPEA announced that it had made a mistake and that “only” 26 per cent of Brazilians agreed with that statement, the debate rapidly lost momentum (Beatriz Moreira da Gama Malcher, “#Feminismo: Ciberativismo e os Sentidos da Visibilidade” - Anais do 40o Encontro Anual da Anpocs, Caxambu, MG, 2016). This does not mean, however, that it did not leave a legacy.

Thus, while we recognise that online mobilising is intimately linked to action on the streets, it is clear that for the feminist movement, social media functions as centres for the elaboration of discourse, as Medeiros points out.2222. This concept is used by Medeiros (Jonas Marcondes Sarubi de Medeiros, “Movimentos de Mulheres Periféricas na Zona Leste de São Paulo: Ciclos Políticos, Redes Discursivas e Contrapúblicos,” PhD thesis - Faculdade de Educação da Universidade de Campinas, 2017) in the sense that Sader (Éder Sader, Quando Novos Personagens Entraram em Cena: Experiências, Falas e Lutas dos Trabalhadores da Grande São Paulo (1970-80) - Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1988 - : 142-3) developed for the term to discuss the origins of new meanings for social movements. These centres are spaces where experiences are reworked to give them a new meaning. The internet is providing the infrastructure needed to promote direct and immediate access to debates and texts. By doing so, it is substituting what was said to be a central characteristic of the previous cycle of Brazilian feminism identified as institutional feminism: mediation by “external” feminist technical advisory groups, such as specialised NGOs.

The relationship between women and their rights and the internet has, however, proven to be extremely paradoxical: social media has also become a hostile space imbued with extreme risks for women. Women are disproportionately affected by trolls2323. Kirsti K. Cole, “‘It’s Like She’s Eager to be Verbally Abused’: Twitter, Trolls, and (En) Gendering Disciplinary Rhetoric,” Feminist Media Studies 15 (2015): 356-358. and online aggression,2424. Emma A. Jane, “‘You’re a Ugly Whorish Slut’ - Understanding E-bile”, Feminist Media Studies 14, no. 4 (2012): 531-546. and gender violence practices such as the non-consensual dissemination of intimate images (NCII) – a phenomenon known as revenge porn2525. The term is problematic and should be dropped from the public debate. The practice is not pornography (which should be understood as legal and consensual, and may be related to pleasure), nor is it related to revenge (which is absent in the majority of cases and, even when the term is evoked in discourse, it establishes a link between a violation of sexual autonomy and a previous act of the victim). Our study on NCII in Brazil analysed all the legal rulings on the issue handed down by the São Paulo Court of Justice up until 2015 and identified that over 90 per cent of the victims who filed complaints were women (Mariana Giorgetti Valente, Natália Neris, Juliana P. Ruiz and Lucas Bulgarelli, O Corpo é o Código: Estratégias Jurídicas de Enfrentamento ao Revenge Porn no Brasil - InternetLab: São Paulo, 2016 -, accessed July 5, 2018, http://www.internetlab.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/OCorpoOCodigo.pdf). Even though NCII can affect men and women, the consequences are felt mainly by women (and also by other people with sexual orientations and identities that are considered dissident).– have reached alarming levels. Violence against women on the internet has taken on multiple and multifaceted forms.2626. “Violências de Gênero na Internet: Diagnóstico, Soluções e Desafios. Contribuição Conjunta do Brasil para a Relatora Especial da ONU Sobre Violência Contra a Mulher,” Coding Rights and Internetlab, 2017, accessed July 5, 2018, http://www.internetlab.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Relatorio_ViolenciaGenero_ONU.pdf. There is also plenty of evidence that they are more common and have more severe consequences when they affect black and indigenous women, people living with disabilities, lesbians, bisexuals and transsexuals. For years, the debate held at the intersection between digital rights and feminisms discussed which aspect should be prioritised: the opportunities for emancipation that the internet offers social movements, or the violence and risks involved in the use of social media.2727. While this is the focus of the recent debate among civil society organisations and the public policy field, there is a historical version of it, with its own terms, in feminist epistemology. In the 1970s, feminist sociology of science began to study the impacts of technology on women and radical and socialist feminists interpreted technology as an extension of patriarchal power. Harding (Sandra Harding, The Science Question in Feminism - New York: Cornell University Press, 1986) observed that feminist critiques of science went from discussing the uses of technology and its risks and opportunities to debating how science, which appears so steeped in masculine endeavours, can be used for emancipatory ends (Judy Wajcman, Technofeminism - Oxford: Polity, 2004). For Harding, in this process, the “woman question” in science was transformed into the “science question” in feminism. Over the past five years, it gradually became clear that it is not a matter of choosing one or the other, but rather recognising that one and the other are both present.

This was due to a change not only in discourse, but also in the internet itself. Thanks to advances in technology, over 20 years, the internet ceased to be a mere set of forums and chats for most people. It now allows people to create true digital selves who are individualisable and enrichened with an abundance of images, videos and precise information on location, preferences and activities. We can call this change embodiment: while the online experience in the 1990s could be dissociated from the material existence of the people who communicated on the web to a certain extent, the digital world later penetrated people’s bodies and people’s bodies entered the digital world. This brought questions of identity and sexuality to the centre of people’s experience on social media, which is inseparable from their experience outside of it.2828. Larissa Pelúcio,“O Amor em Tempo de Aplicativos: Notas Afetivas e Metodológicas Sobre Pesquisas com Mídias Digitais,” in No Emaranhado da Rede: Gênero, Sexualidade e Mídia; Desafios Teóricos e Metodológicos do Presente, Larissa Pelúcio, Heloísa Pait and Thiago Sabatine (São Paulo: Annablume, 2015). And discrimination and violence against women’s bodies easily found their double in the digital world.

This paradox can be more easily understood if we adopt Nancy Fraser’s perspective on the public sphere, which is a criticism of Jürgen Habermas’s earlier formulation of the concept. Fraser argues that there is no one, single public sphere that contemplates all the discursive exchanges in any given society – nor would it be desirable to have only one – but rather a plurality of publics that compete with one another. And, throughout history, there have always been what the author calls subaltern counterpublics – that is, alternative discursive arenas in which members of subalternate groups invent their counter discourses and “formulate oppositional interpretations of their identities, interests and needs”.2929. Nancy Fraser, “Rethinking the Public Sphere: A Contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy,” in Habermas and the Public Sphere, org. Craig Calhoun (Cambridge: MIT, 1992). This was the case of US feminists at the end of the 20th century who organised their own means of communication, publishing houses, book stores, academic programmes, conferences and meeting places and developed a language that conveys demands and works to reduce inequality – terms such as “rape culture”, “double day” and “sexual harassment” come to mind. This space for elaborating collective self-definitions is also a reality for black women. According to Patricia Hill Collins, in safe spaces, “Black women ‘observe the feminine images of the ‘larger’ culture, realize that these models are at best unsuitable and at worst destructive to them, and go about the business of fashioning themselves after the prevalent, historical black female role models in their own community”.3030. Patricia Hill Collins, Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment (New York, London: Routledge, 2000). Hill Collins identified these safe spaces in writing, music (especially in blues) and black women’s relationships with one another in the 20th century in the United States.

Today, on social media, feminist demands are being formulated according to the logic of a subaltern counterpublic, which although it has not been generalised, it does negotiate with the hegemonic public sphere and other counterpublics in its quest to expand continuously. And, in this negotiating process, confrontations and reactions occur.

The coexistence of these public spheres on the internet is not transparent, as one might think. One of the reasons for this is the “filter bubble” – a concept elaborated by Eli Pariser3131. Eli Pariser, The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding From You (New York: Penguin Press, 2011). to explain how algorithms personalise the experience on digital platforms and work to expose people mostly to content that is close to their preferences and opinions. It is in this context that observations of interactions on social media gain importance. Using data from the Political Debate in the Digital World Monitor from the University of São Paulo,3232. We thank Pablo Ortellado and Marcio Moretto Ribeiro for providing us access to the project data. we conducted a study on communication on gender issues on Facebook during the week of International Women’s Day (March 8) in 2018 – a period in which the debate on issues related to women and their rights intensifies. The Political Debate in the Digital World Monitor gathers information on posts shared on over 500 Facebook pages that focus on the political debate in Brazil, which it then classifies into two categories. The categories are a reflection of how the researchers for the project have come to understand, based on the data, the current polarisation in the country’s political debate: on one hand, there is the anti-PT (Workers’ Party) side formed by liberals, conservatives, people calling for military intervention and political parties from the current government’s base of allies; on the other hand is the anti-anti-PT side, made up of NGOs, opposition parties, left-wing groups and social movements, including the pages of the feminist, anti-racist and LGBT movement. This polarisation can clearly be observed from the activity on these Facebook pages, as individuals who follow some pages also follow others from the same side, but rarely follow pages from the opposite side.

Many individuals who like posts on pages defending liberal positions on the economy also like posts on pages with conservative positions on customs. On the other hand, the ones who like posts on left-wing pages also like posts on feminist pages. One group of pages is distanced from the other: it is very rare that someone who likes content shared on a liberal page in economic terms also likes posts on a feminist page.3333. Bernardo Sorj, Francisco Brito Cruz, Maike Wile dos Santos and Marcio Moretto Ribeiro, Sobrevivendo nas Redes: Guia do Cidadão (São Paulo: Plataforma Democrática, 2018).

Resorting to a simplification, we identified one pole as “progressive” and the other as “conservative”. Feminist pages were included in the progressive pole – in other words, individuals who engage with them also engage on other issues from this field. The Political Debate in the Digital World Monitor also collects news shared on Facebook from 96 news sites.

We filtered all the posts from pages and news shared that week containing the words “woman”, “feminism”, “gender” and “harassment”,3434. The choice of the word assédio (harassment) was linked to the researchers’ hypothesis that the harassment issue has been unifying different demands for equality and the elimination of all forms of violence against women defended by Brazilian feminists in the debate on the internet. and obtained 1,382 posts3535. The full list is available in the “noticias_SemanaMulher1” spreadsheet, Internetlab, 2018, accessed July 5, 2018, http://www.internetlab.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/noticias_SemanaMulher1.xlsx. and 625 shares of news reports.3636. The full list is available in the “posts-semanaMulher” spreadsheet, Internetlab, 2018, accessed July 5, 2018, http://www.internetlab.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/posts-semanaMulher.xlsx. As feminist researchers and members of networks of human rights defenders, we expected to find a series of debates on women’s rights on the progressive side and to be able to map the issues that mobilised the subaltern counterpublic that discusses feminism on the internet the most. The results showed a completely different picture: even during such a particular week, the debate was divided between the two poles and the pages that stood out the most were actually from the conservative side, which, largely treated feminists’ demands with irony.

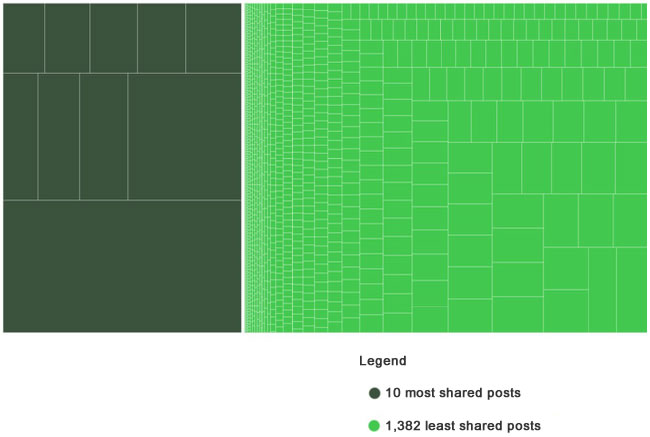

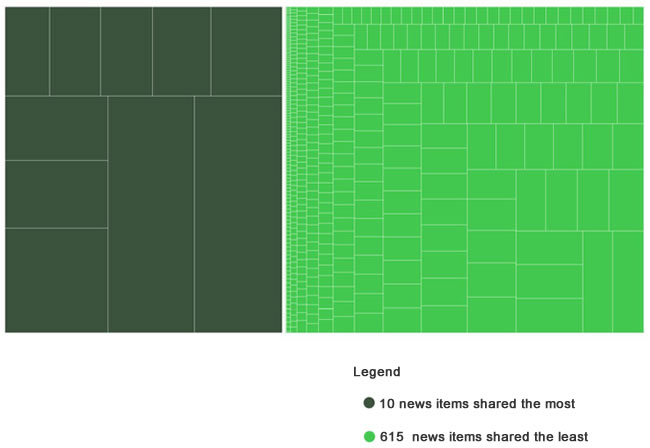

The first important observation to be made on the patterns of the debate is that while we are talking about a large number of posts with different content being shared, their reach varies greatly. The number of shares for each post varies from 14,175 shares to only 1; the number of times the ten most shared posts was shared is practically the equivalent of the total shares for the 1,382 remaining posts.3737. When we saw the results, we sought to establish criteria for a qualitative analysis by creating ranges of shares based on proportions. None of the most obvious criteria, such as the “ten posts shared the most” or “the fifty stories shared the most”, appeared to make sense. This is because the difference in proportions did not fit into quantitatively similar brackets: the number of shares obtained by the post shared the most more than doubled that the amount obtained by the second on the list; the second post shared the most, for its part, exceeded the third runner up more than three times, and so on, with significant variations in the number of shares from one post to the next. The graph below helps to visualise these proportions:

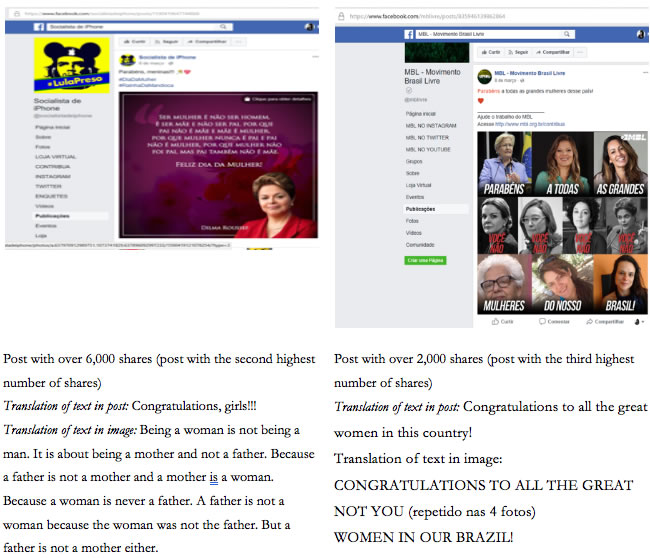

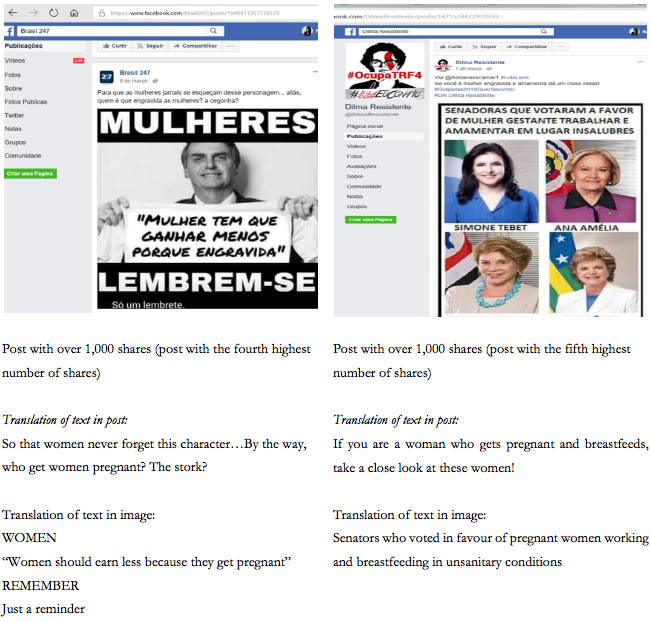

The majority of the posts with the highest number of shares came from pages not on the progressive side, but rather the conservative side: Jair Bolsonaro Presidente 2018 (Jair Bolsonaro for President 2018),3838. One post from this page was shared the most during the period (with over 14,000 shares), but the content was removed before we could analyse it. followed by Socialista de Iphone (Iphone Socialists), Movimento Brasil Livre (Free Brazil Movement), Movimento Contra-Corrupção e Anti-PT (Anti-corruption and Anti-PT Movement). Three of the posts shared the most came from pages on the progressive side: Brasil 247, Dilma Resistente (Dilma Resists) and Manuela D’Ávila.

In addition to the concentration of the impact of posts from conservative pages, one can also note that during that week, the debate on women was largely monopolised by issues that have more to do with the political polarisation affecting Brazil than ones related to women’s rights per se. The second most shared post is a meme satirising former president Dilma Rousseff, which contains a confused and poorly articulated statement on what it means to be a woman. While the meme in question is a joke about the way she talks, it is actually mocking the women’s agenda by evoking the only woman president Brazil has had on March 8. The third most shared post separates women who “deserve to be congratulated” from those who do not based on their position in the polarised political field: the ones from the conservative camp are the real women who should be celebrated. Even on the progressive side, the post with the most shares are the memes celebrating women politicians who voted a certain way, or campaigning against conservative candidates who attack women’s demands. None of the most shared posts transcend the focus on individuals and this short-sighted polarisation.3939. This result is particularly interesting when we take into account a similar experiment that adopted the Day of Black Consciousness as a reference. We found that cases of racism against individuals (especially famous people) occupied a more central place on the debate than discussions that are dear to the black movement, such as structural racism, genocide and reversals in public policies promoting racial equality. See Natália Neris and Lucas Lago, “Como se Discute Racismo na Internet? Um Experimento com Dados no Mês da Consciência Negra.” Internetlab, February 26, 2018, accessed July 5, 2018, http://www.internetlab.org.br/pt/desigualdades-e-identidades/como-se-discute-racismo-na-internet-um-experimento-com-dados-no-mes-da-consciencia-negra/.

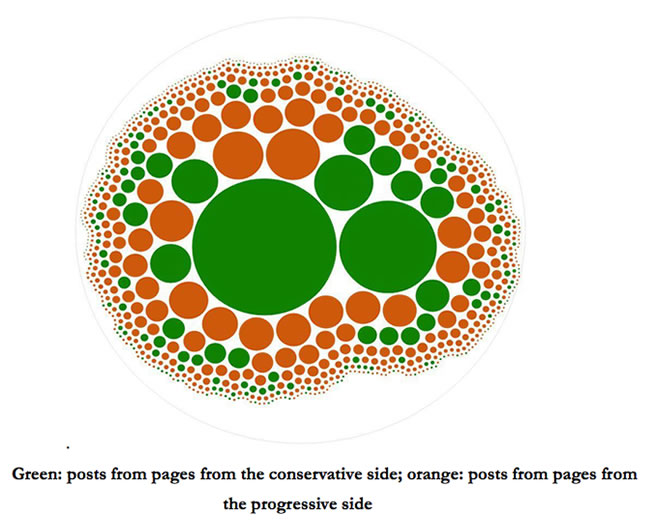

When we separate the posts according to the political spectrum of the pages, as classified by the Political Debate in the Digital World Monitor, other patterns appear. Much more content was produced by pages from the progressive side, which engaged in more intense activism during the period. This was what we expected, as feminist pages are part of this group. Even so, the posts from conservative pages got many more shares (and, in fact, appear at the top of the list):4040. See structural analyses carried out on the pages from both spectrums in September 2017: “Análise Estrutural das Páginas de Direita no Facebook,” Página do Facebook de Monitor do Debate Político no Meio Digital, September 12, 2017, accessed July 5, 2018, https://www.facebook.com/monitordodebatepolitico/photos/a.1067365179991611.1073741828.1066344906760305/1536950463033078/?type=3&theater; and “Analise Estrutural das Páginas Progressistas no Facebook,” Página do Facebook de Monitor do Debate Político no Meio Digital, September 16, 2017, accessed July 5, 2018, https://www.facebook.com/monitordodebatepolitico/photos/a.1067365179991611.1073741828.1066344906760305/1540281482699976/?type=3&theater.

In the case of the sharing of news reports, we also observed – though to a lesser extent – that shares were highly concentrated in only a few links:

The most shared news reports came from mainstream media outlets, namely the Estado de São Paulo, G1 (Globo), R7 (Record), Veja and BBC Brazil websites.4141. For a more in-depth discussion on concentration in the internet, see the study entitled “Concentração e Diversidade na Internet,” Intervozes, Monopólios Digitais, 2018, accessed July 5, 2018. The study’s main result can be summarised as follows: while on one hand, there are more agents in the applications and content layer on the internet than in other means of communication, such as TV, on the other hand, the hegemony of the major platforms and the large national media groups in these new kinds of media call into question the idea that the internet is a space for more democratic communication. The two news items that were circulated the most got a little over 47,000 shares. The articles were about the launch of Barbie dolls made in the image of three famous women (Frida Kahlo, Amelia Earhart and Katherine Johnson) and a list from the Buzzfeed website with testimonies on inequality in the labour market shared by women in response to a question launched by the Ministry of Labour on Twitter. The third news item with the most shares told the story of a woman pilot who flew the presidential plane, which had a little over 24,000 shares; the fourth reproduced the story on the launch of the Barbie dolls, and the fifth presented the historical origins of March 8. Therefore, topics related to women’s rights and structural issues (feminicides, transphobia, inequalities on the labour market, approval of laws to combat violence and the trajectory of black women) shared space with an article with commercial content. In any case, contrary to what happened in the debate generated by Facebook pages, the media is still strongly influenced by feminist activism.

The observation of patterns of communication on Facebook during the week of the 2018 International Women’s Day concretises a part of the discussion on the relation between feminist activism and the internet. On one hand, there is the power of online activism and its capacity to influence mainstream media, whose content is then shared on the internet. On the other, hegemonic (and anti-equality) discourses on women and their demands continue to have considerable reach in the conversations between Facebook page administrators.

Even though more counter discourse content was produced, conservative narratives continue to be heard more. It should be said that in addition to the reasons rooted in society, what is at stake here are the issues related to specific ways of circulating information on the internet, or how they are or can be manipulated by actors from the field of communications. We know that algorithms determine the reach of the information posted and that, on a platform like Facebook, increasing one’s reach has to do with mastering a certain kind of language that “goes viral” and with using financial resources to boost content and pages. We also know that these rules lack transparency and are formulated with little interference from users. This kind of interference happens occasionally when the public manages to exert considerable pressure and affect the companies’ public image. In a context where online activities are highly concentrated on a few platforms, as in the case of Facebook for social media and YouTube for videos, the boundaries of the digital debate also remain concentrated in only a handful of corporate actors.

Another point is that content on individual women in these pages’ posts leads to a proliferation of misogynous hate speech in the comments in the form of swearing, attacks and disqualifications. Our observations indicate that women communicators in the broad sense of the term – that is, activists, journalists, actors and politicians – have been the prime target for this type of violence, regardless of whether they are talking about feminism or not.4242. “Violências de Gênero na Internet,” Coding Rights and Internetlab, 2017. The platforms, for their part, are finding it a major challenge to define and ban hate speech, as the sectors defending conservative agendas that infringe the freedom of expression can capitalise on demands for censorship – which victimises us as women once again. What is more, even if the challenges are big, the platforms are private and lack transparency, and the raising of our voices is increasingly met with virtual attacks, we believe that we cannot give up these spaces, which have allowed this subaltern counterpublic to grow. This means we must fight for these spaces and demand that the platforms adopt gender-sensitive policies, reflect on and formulation digital security measures for subaltern groups, invest in real access to the internet for women, especially black and indigenous women, and take policies of access to knowledge seriously. This is the broad agenda of research and actions needed to feminise the internet and that we hope to continue to build with different men and women actors.