This paper aims to advance the discussion on how to deal with new internal and external security problems in Latin America, both old and new. Part I examines the concept of human security, particularly in Latin America, and considers criticisms in international literature. We argue that human security is more than a normative framework and must be reformulated into an operational and analytical tool. Human security-oriented analysis needs to have a clearer focus on armed violence; the institutional dimensions must also be taken in consideration, within a perspective of variable geometry of international security problems. Part II begins with a short review of the current security problems in Latin America – and the new situation produced by United States anti-terrorism policies. Here we also discuss some of the difficulties in consolidating a common Latin American international agenda. The final section lays out some of the main issues that could be taken on by researchers, civil society and policy makers in Latin America.

The concept of human security was first introduced in a 1994 UNDP report,1 though the basis for this formulation has long been present within the United Nations. The founding charter of the UN and several subsequent documents mention national sovereignty as an organizing axis of the international system, as well as the defense of human rights regardless of frontiers. In other words, since its origin the United Nations system recognizes two lines of “absolute” values that the international system should aim to protect: national sovereignty and the human rights of individuals.

Currently, support for the concept of human security lies mainly in the new constellation of post-cold war international actors. This support stems from the fact that much of today’s physical insecurity derives from internal armed conflicts rather than wars between states. These may be civil wars or less clearly-defined conflicts between armed gangs or terrorist groups, sometimes supported directly or indirectly by states with a weak commitment to human rights.

The concept of human security is innovative in its emphasis on enforcement of individual human rights. This is considered as the principal task of international order, even against the will of the states, which are mentioned as one of the main sources of individual insecurity. However, as we will see, in spite of its focus on individuals, human security can not be separated from institutional frameworks, particularly nation-states under which human rights are (or are not) implemented.

The emphasis on a vision that is no longer centered exclusively on sovereign nation-states promotes new forms of multilateralism, in which non-governmental actors, particularly NGOs, play a central role.2

Today there are several different views of human security circulating in the international sphere. The version proposed by the Human Security Commission – presided over by Sadako Ogasa and Amartya Sen3 and supported by the Japanese government – is particularly broad and conceptually diffuse. Seeking to add risks and threats to physical and environmental security to the UNDP concept of human development (such as epidemics, availability of medicine, poverty, provision of water, development and economic crises, use of firearms and physical violence, ecological disasters) this notion of human security suggests a holistic but not very precise vision of what a national or international policy of security/insecurity should be.

More focused visions, particularly those put forward by the Canadian government and researchers from Canada, hold that human security has five characteristics:4

1. It is a holistic concept comprising all the diverse sources of individual insecurity, including those related to poverty as well as physical violence.

2. It is centered on the human rights of individuals. In fact, it emphasizes the role of government as a source of insecurity for its citizens.

3. It values civil society as a privileged actor, implicitly diminishing the role of government.

4. It aims to have a global perspective.

5. It justifies external intervention by the international community in countries going through humanitarian crises.

A report entitled “A Human Security Doctrine for Europe”, presented recently to the EU High Representative for Common Policy and Security Policy, presents a more precise strategic focus.5 The report highlights regional conflicts and failed states, advocating “… preventive engagement and effective multilateralism” (p. 6). In the current context, this approach is considered better than containment in terms of facilitating democratic transition. This is based on the diagnosis that inter-state conflicts have decreased while new dangers related to “… lawlessness, impoverishment, exclusivist ideologies and the daily use of violence” (p. 7) have gained prominence. Hence, the five key threats to Europe are: “… terrorism, the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, regional conflicts, failing states, and organized crime” (p. 8). The main sources of the threats are authoritarian states with repressive policies or state and non-state armed groups in failed states. It proposes to advance a clear legal framework for justified interventions. It also calls for operations on the ground that are based on the principles of human rights, clear political authority, multilateralism, a bottom-up approach, regional focus, the use of legal instruments, and the appropriate use of force.

The concept of human security grew out of efforts to delimit a new doctrine for the international system in which human rights and development issues have a central role. It is a direct product of the end of the Cold War and of the structuring role that the human rights discourse came to play in international forums. The United Nations and small as well as medium-sized developed countries involved in international cooperation (such as Canada and Norway) pushed this new agenda beginning in the mid-1990s. Later, other European countries and Japan also came on board.6

There have been different actors and objectives behind the human security agenda. For the United Nations, particularly under Secretary General Kofi Annan, the aim was to create a discourse that would free the United Nations from submission to national sovereignty as the only source of legitimacy for international action. For medium-sized developed countries not aiming to project their military power, this was a doctrine that would orient international relations and, in particular, international cooperation. Latin American countries support, as we will see, a specific formulation of human security (multidimensional security) as a way to confront the United States’ securitizing agenda. African countries, on the other hand, see human security as a concept that will allow them to increase their capacity to negotiate international support. Recently, as we have mentioned, the European Union has been using the concept to baptize their new foreign policy. Finally, over the past few years, a human security approach has been adopted by several NGOs and, in Latin America, even by some institutions of public order. For international NGOs, the human security perspective reinforces their self-image as beyond-border guardians of human rights, while national NGOs and government institutions tend to reduce/reorient the concept to internal security/public order issues.7

As a conceptual framework, the idea of security/insecurity is so general that it can be argued – and many do – that it is the nature of modern capitalist society to foment perceived insecurities (even to the point of being defined as a “risk society”). The international relations bibliography has the following main criticisms of the concept of human security:8

• It does not have a vision of power or the political institutions necessary for ensuring the effective implementation of human rights, including repression when necessary.

• It dilutes the specific problems of the struggle against physical violence within an agenda that, in the end, includes every possible source of insecurity, confusing different causal factors.

• It loses operational capacity by fusing very different social problems. In complex societies, the diverse areas included within the human security agenda are distributed among different sub-systems with relative operational autonomy and varied responsibilities (the armed forces, public health, social policies, and environmental policies). As a holistic concept that is not translated in analytical operational terms, this notion of human security is incapable of defining priorities and distributing responsibilities.

• It has a narrow and reductionist view of the state (in fact, individual security has always been present in the modern state) and an exaggerated emphasis on the role of civil society. It loses sight of the fact that public security and the protection of citizens cannot occur without solid institutions to guarantee public order and provision of justice.

The majority of human rights NGOs and the academic community in Latin America have so far tended to be critical of the concept of human security. To understand this criticism, one must think back to the continent’s recent past, when military dictatorships used the all-inclusive doctrine of National Security to subsume various aspects of social life to the fight against communism and “national defense”. Within this doctrine, public security forces including the police were under control of the armed forces. A major goal of democratization, then, was to reign in the armed forces. New constitutions restricted the armed forces’ mandate to defending the national territory against external enemies, taking them out of functions related to internal security.

In this context, a human security perspective is seen as an attempt to “resecuritize” social life, placing social problems within the scope of security. (Paradoxically, when the concept of human security was introduced, the intent was just the opposite: to broaden considerations of security problems in order to bring interrelationships with broader social problems into focus.)

Further, the concept of human security generates certain unease in intellectual circles as well as in the armed forces insofar as it was developed in opposition to a vision of international relations based on national sovereignty. The foreign policies of Latin American countries in the 20th century were centered on the value of national sovereignty, which is comprehensible given the latent fear of an invasion by the United States. In spite of these criticisms we believe that it is possible and perhaps even advisable to continue working with the concept of human security in the region. After all, it is the only existing conceptual framework in which to develop a multilateral vision and respect for human rights and social development in international relations. However, we also believe it is necessary to define a more precise focus for analysis.

The concept of human security can be viewed as embodying different, albeit not contradictory, meanings. Different social actors also put it into practice in different ways. One way in which the concept is defined is fundamentally normative, defining a moral horizon for international relations and societies in which all human rights are guaranteed. Another way sees human security as a semantic field, rather than as a defined set of normative principles or conceptual tool. In this view, human security is understood as a loose conceptual framework that creates a common ground for dialogue among different actors in search of an international security agenda that prioritizes the problems of development and enforcement of human rights. A third reading of the concept, which will be explored in some detail in this paper, seeks to transform human security into an operationally relevant and analytically useful concept for social scientists.

An operational and analytically relevant concept of human security should:

• Produce a more narrow focus of “insecurity”. At the crux of the concept of human security is protection from organized or uncontrolled armed violence that is capable of threatening: (1) the stability of local democratic institutions; and/or (2) the physical safety of the population; and/or (3) produce an international community’s reaction (for instance, in the case of a genocide or training terrorists). Hence, humanitarian crises related to famine, health epidemics, or natural or ecological disasters are not included within a more focused concept of human security. We believe it would not be difficult, although it is beyond the scope of this paper, to argue the moral and political importance of differentiating between these types of humanitarian (or ecological or health epidemic) crises and destruction produced by intentional human violence.

• Include an analysis of the institutional and social framework under which human security is, or is not, assured. In fact the institutional framework is at the center of the different policies oriented by a human security analysis. Most of the cases of humanitarian or international intervention refer either to failing states or countries that are going through humanitarian crises. In both cases the basic problems are related to failing institutions. Undue emphasis on the capacity of NGOs and civil society in general to solve security problems is unrealistic, inefficient and escapist, not confronting the issues of strengthening the democratic state institutions. There is no individual human security outside a state with political and administrative structures capable of assuring it.

• Relate security and development issues without submitting one to the other. A security agenda that is insensitive to issues of global and national inequality, epidemics, environment deterioration, disillusionment and relative deprivation will be condemned to fighting a war against symptoms. A developmental economics agenda that reduces security issues to an epiphenomenon that doesn’t need specific treatment, investments and institutional build-up will find itself with a mounting problem that could eventually lead to authoritarian regimes and even state collapse.

From a Latin American perspective, human security should:

• Not conflate diverse social problems. While social problems are inter-related, each one possesses specific dynamics and requires specific policies and institutions. Recognizing the inter-relationships between problems, such as violence and poverty, should not imply a reductionist view of social problems. Sociological research has shown that it is not necessarily the poorest sectors of the urban population that get involved in crime and that armed violence, once consolidated, has a dynamic that is autonomous up to a certain point. In the same way, many of the problems placed on the multidimensional agenda refer to problems fundamentally associated with internal politics. We cannot forget, for example, that poverty in Latin America is sustained, above all, by social inequalities, corruption, and by the inefficiency of social policies.

• Develop an operational vision with a special focus on state institution building, which includes the participation of civil society but which ultimate goal is to assure the functioning of a state based on the rule of law. Human security-oriented research and action should focus on the insecurity resulting from armed violence, within a perspective that considers respect for human rights and comprehends the social context that generates such violence. Thus the prevention and repression of violence should act on the immediate causes as well as social contexts – in particular on the social groups most at-risk to be victimized by or involved in armed violence and crime.

• Advance not only an international but also a national multilateral approach to security problems, in which different stakeholders (inter alia, public institutions, NGOs, entrepreneurial and community associations) discuss and advance new approaches and policies.

• Recognize that in concrete situations there can be tensions between a universalistic view of human rights (or the defense of ecology) and the recognition of sovereignty as one of the pillars of the international system. While extreme cases can be handled by international courts many situations bear a level of ambiguity which requires open spirit and dialogue. At a local level it is important to increase the interaction between institutions responsible for the national defense and NGOs struggling for human rights. Otherwise mistrust and mutual recrimination will only hamper the advance of a more democratic agenda.

• Relate to the global debate on security within a variable geometry perspective. This means emphasizing that global concepts and agendas are only meaningful if they recognize the specificities of local conditions, and that they are only relevant insofar as they are useful for comparative analysis. Further, they should include different variations and typologies and not seek to be all-embracing simplifications of the style advanced by international agencies and the US government. More specifically, in Latin America – where countries are not major players in terms of military or humanitarian aid, nor are they rogue or collapsed states – the focus of human security should be on internal problems of public order that may have international consequences. The same variable geometry approach should be applied internally to Latin America, where seeking a common denominator has tended to generate very general and non-operational proposals. Sub-regional and bilateral agreements provide more realistic bases from which to advance a common security agenda. A human security agenda should be built from the local toward the global instead of the current tendency to produce global concepts and apply to national situations.

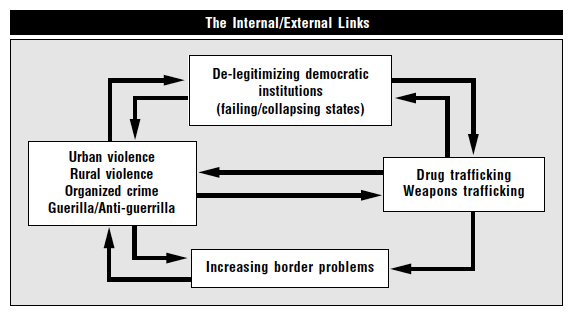

Urban violence has increasingly taken hold of larger cities in Latin America and is becoming more and more associated with international drug trafficking, arms dealing and money laundering; these activities do not respect national borders and combating them depends on a multilateral effort by states in the region. Guerrilla warfare, previously in Central America and now in Colombia, has generated refugee problems and created tensions at the borders. Although international terrorist groups are not important overall, they do have (or had) certain significance around the triple border region between Brazil, Argentina and Paraguay.

Although inter-state armed conflict is not a relevant issue in Latin America today, the impact of violence and politics under the influence of drug production and organized crime (and guerilla warfare in Colombia) have the potential to inflame inter-state conflicts and produce problematic regions, such as the triple border region and particularly the Amazon region. Perhaps even more importantly, they may result in a democratically elected government that could fall within the Bush doctrine of failing or terrorist-sympathizer states. Thus, the links between internal and external security problems can produce failing states as much as they can destroy state-building efforts in the region.

Latin America constitutes the region of the world with the lowest levels of armed conflicts between states and the lowest military expenditures in relation to GNP. The region has consolidated borders, and is for the most part absent of intra-religious conflicts and strong ethnic hatred. Latin America is the only region in the world where all the countries adhered to an anti-nuclear weapons treaty.

The decade of the 1990s, which we could call a period of “blue globalization”, was a period of democratic consolidation on the continent. The agenda of the international system in general, and of United States/Latin America relations in particular, were dominated by economic themes and by the expectation that globalization, as well as new forms of economic regulation, would generate a system of international political governance founded in multilateralism. With the new millennium, analysts saw that the tides were quickly turning. Economic globalization did not produce expressive gains for a good part of the population of Latin American countries in this new era of “gray globalization”.

The Bush administration adopted a more self-contained posture in US international foreign policy with regard to institutional arrangements and supranational treaties. Following the events of September 11th, the United States redefined its strategic position as strongly unilateralist, and its foreign policy became focused almost exclusively around the fight against terrorism. Indeed, the term “terrorism” has come to be applied to practically all the organizations considered to be enemies of the US government, in many cases without any tie to international terrorism.9 The fight against terrorism and resulting American interventions were made under the guise of protecting human rights. This caused some doubts about the right of justifying external intervention in the name of human security.

The Bush government reproduced the same polarization and consequent automatic alignment to US foreign policy as had been experienced in the period of communism. It has mainly failed and some changes are likely to be introduced in its second administration. In any case, the new international scenario can not be simplistically fit into the Bush doctrine. One can not ignore transformations in the international order brought by the events of September 11th and the ways that the fight against terrorism is changing international security strategies. The issue is not to deny the problem but to participate actively in defining the threats and different ways to confront them.

In the new context of militarization of international relations, all these factors have led the United States to marginalize Latin America in its system of priorities. This marginalization has deepened because the fight against terrorism is not seen as a priority security issue within the region, despite US efforts to polarize the world around this subject. In Latin America the fight against terrorism does not fill the space left by the fight against communism, which had the support of most of the dominant groups, the middle classes, and the local armed forces.

The region presents its own weaknesses in the international arena. In past decades, Latin American countries were not able to develop a shared vision of their security problems, nor a concrete agenda for action. Even more than Europe or Japan, Latin American countries are free riders in the international scene. While they enjoy the strategic umbrella of the United States, Latin American countries often feel they are victimized by the hegemonic power of their overbearing neighbor from the north. After the anti-communist struggle, different countries presented perspectives and priorities that varied considerably in terms of reorganizing the inter-American institutional system and defining security priorities in the region. The United States is the only country on the continent that presents a proposal for hemispheric security, while Latin American countries tend to favor local perspectives/interests and a defensive posture.

Without a doubt, the 1990s brought certain novelties and advances in the region, such as setting democratic order as a central factor for maintaining peace. Another new element was subregional agreements (Mercosur, Andean Area and Central America) with positive political-institutional implications for democratic consolidation. Even so, the common element of foreign policy in Latin America continues to hinge on the principle of non-intervention and on efforts to undermine or limit the capacity of the United States to impose its agenda on countries in the region.10 Faced with the United States’ tendency to securitize the international agenda, Latin American countries have emphasized the pluridimensionality of the hemispheric security agenda, prioritizing problems associated with poverty, health, the environment and economic development.

During the anti-communist struggle, security apparatuses became more autonomous, particularly the armed forces. They developed doctrines of defense and public order centered in the notion of National Security and called for stronger armed forces, presenting themselves as representatives or defenders of the national interest in the struggle against the internal enemy – communism – and the external enemy – bordering countries. However, with the end of communism the main historical enemy evaporated and the processes of democratization (with civil governments focusing on internal national and social problems) reduced intra-national tensions.11

In recent years important advances were made in building trust and collaboration between armed forces that had traditionally been rivals (particularly between Chile and Argentina or Brazil and Argentina). However, the armed forces in Latin America continue to be largely immune to democratization processes (in the sense of being open to public debate and to redefining their doctrine, which continues to be anchored in the notion of National Security). Thus, there is a dissonance between the military doctrine and the dominant political discourse, which emphasizes democracy and human rights. This is reflected even in the limited number of academic research centers and civil society organizations in Latin American countries that focus on monitoring the armed forces and police.

The way reality is perceived and conceptualized plays a fundamental role in the social realm. The Bush doctrine of war against terror may have a major impact on Latin American security systems and has the capacity to galvanize and polarize Latin American politics around a love/hate axis. Possibly one of the worst consequences of the current US anti-terror doctrine is that many Latin American politicians and intellectuals are able to gain recognition and popularity only by criticizing the United States government position. This allows them to avoid analyzing and confronting the continent’s genuine security problems, including the development of an effective security doctrine capable of facing up to the US anti-terror agenda.

During the fight against communism, United States foreign policy found important support in different social and political sectors in Latin America, where communism was seen as a common enemy. However, the fight against terrorism does not mobilize local support as none of the Latin American social groups consider this struggle a priority. Furthermore, for the armed forces, particularly in Brazil, the US has become a main source of concern, especially due to its presence in neighboring Colombia and worries about a conspiracy to internationalize the Amazonian region. In this context, the use of anti-American slogans can be an easy way to gain public support, and can become a source of international strain.

Easy anti-USA rhetoric is one of the obstacles to advancing a Latin American security agenda. In some cases like Colombia – seen by many in Latin America as “contaminated” by the strong US presence there – it affects the capacity to analyze and to advance an alternative, non-reactive, agenda. However, more specific issues are at stake.

Traditionally, the area of international relations was not a central field of inquiry among most of the leading Latin American social scientists. Although there are some relevant groups of researchers in the area, their approach is generally mostly traditional – that is, focused on foreign relations and international trade. At the same time, in recent decades, Latin American social scientists and NGOs have advanced research and practical proposals in the area of internal violence/security problems, focusing mainly on violence as an internal problem. There is a clear need for more research and discussions among practitioners on the internal/externallinks of violence and security and international relations issues. From the 1980s on, Latin American social scientists tended to focus on their own countries, abandoning comparative Latin American studies. This was a product of the defeat of the left, which had a regional perspective. It also reflects the specificity of the new democratic realities and their internationalization, which created closer ties with academic centers in developed countries. Most of the NGOs with a generally stronger Latin American focus do not have solid research capabilities.

Latin American countries’ foreign policies have so far tried to confront the US anti-terror doctrine with a concept of “multidimensional security”, which is quite close to that of human security, except that it does not include the idea of humanitarian intervention. The concept of multidimensional security identifies problems related to drug and arms trafficking, terrorism, health, poverty, economic crises and the environment as sources of insecurity, among others. Clearly this is not a proposal for an effective foreign policy doctrine, and does not confront possible scenarios for intervention. It does, however, counterbalance US foreign policy by relativizing and diluting its emphasis on defense.

Although in recent years an increasing number of Latin American NGOs have begun to focus on security issues, an important number of those focused on human rights have some difficulties advancing an affirmative agenda on security problems. This is partly due to the fact that any operational proposal needs to deal with the effective use of repressive tactics. A false dichotomy has been created between efficiency and transparency. Practical experience shows that efficiency is linked to transparency, but also that the emphasis on transparency should not be separated from a clear understanding of the operational specificities and needs of the security system.

Faced with this reality, the following question arises: In the current context, is it necessary or even possible to try to advance a pro-active Latin American agenda that seeks to confront regional security problems and increase the region’s autonomy on the international playing field? I believe that the answer to both parts of this question is yes. But the principles of non-intervention and opposition to the United States’ agenda are not enough to confront the challenges underway. In the first place, while the United States’ agenda could be reigned in to some extent, it can not be completely controlled. Due to the political, military and economic weight that it wields, the United States can only be confronted with another agenda that permits effective negotiations. That is, multilateralism at the regional level can only be constructed from an agenda that takes into consideration the problems (but not necessarily the diagnosis nor the solutions) raised by United States foreign policy. For the majority of the countries in the region, the relevant problems are: the reality of new forms of organized crime and terror that explode the distinction between internal and external policies; the emergence of problematic border regions associated with drugs, criminals, guerrillas and terrorism; and finally the constitution of territorial spaces, including urban spaces, where the state has lost effective control. Such issues demand new bilateral, sub-regional and regional arrangements, plus a renewed role/strategy for the armed forces and the collective security system in the region.

A pro-active research and practical agenda should confront the following questions:

Latin America needs to confront new internal and external threats with a strategy that reinforces democratic institutions in general and the law enforcement system in particular. We need to advance the discussion on national sovereignty, recognizing that the traditional position based on a closed perspective of sovereignty is no longer viable (and probably never was, but during a certain period it was possible to enjoy the illusion). There is a certain consensus that security problems in today’s world go beyond the limits of national borders and the individual capacity of states to cope with security threats. In fact, in recent years Latin American countries have developed an “interventionist” posture in cases of maintaining democratic institutions. The general tendency for countries in the region to assume “sovereignist” positions is a legitimate attitude, grounded in the desire to create mechanisms that can repel unwanted interventions from the United States. However today’s challenge is to advance an agenda of collective security that develops mechanisms that share decision making and inter-state operational systems, particularly – but not only – in border areas, while maintaining respect for national sovereignty.

New forms of organized violence diluting divisions between national defense and internal public security demand a redefinition of the roles of the armed forces and the police, and increasing cooperation between them. This necessity comes up against various difficulties. Among the political elite of the region, particularly in southern cone countries, there is the recent memory of military interventions. This generates reasonable concern around the autonomy of the armed forces and a tendency to want to delimit their field to external issues and maintain them at the margin of internal questions. Historical experience from the period of the fight against communism also indicates that when they are closely involved with questions of internal security, the armed forces tend to subordinate political forces and their chain of command. (Even today, Brazil’s main police force – the military police – is hierarchically organized in military terms with the highest post being that of colonel, making it dependent on the armed forces). A legitimate concern also exists that the armed forces are contaminated and corrupted by the considerable financial resources of organized crime.

Even so, integration of the armed forces and police is an increasingly present demand. This is because internal and external problems in the region are interlinked, because the borders are key areas in actions against organized crime, and because certain regions of the borders are “colonized” by groups outside the law. What changes are needed in the doctrine and governance of the armed forces in order to integrate them in efforts to quell new forms of violence? At the same time, how can public control be increased so that they do not overstep political boundaries? How can we integrate the police and their intelligence services with those of the armed forces while ensuring that each remains autonomous? How can sub-regional and regional cooperation efforts be developed between police and the armed forces? How can we guarantee shared inter-state mechanisms to control our borders? How can we treat “problematic” regions while preserving national sovereignty? How can we adapt and multiply the region’s achievements and best practices, such as post-conflict reconstruction of the security forces in Central America, police reform experiences in Latin American cities like Bogotá and Mexico City, and projects with risk groups in slums like those developed by Viva Rio in Brazilian favellas? These pressing questions will require concerted efforts and coordinated responses from Latin American countries in light of the new security developments described above.

Since the Latin American research agenda on international relations and security problems and policies is mostly defensive, different stakeholders (including social scientists, NGOs, and governments) tend to avoid discussing the concepts that currently inform the international debate held not only by the United States but also by European and international organizations.

A local debate is needed to advance the regional view(s) of the phenomenon of drugs and terrorism. The current US security doctrine – which equates terrorism with any “anti-American” act, including drug production and trafficking, money laundering, guerrilla and violent political groups – confuses and fuses diverse problems that actually require differentiated solutions. Different types of violence have different social backgrounds and require different solutions. Even if we recognize that some criminal and violent political groups can become interconnected to international terrorist networks, this does not mean that they can be confronted with a common operational framework.

Most violence problems in Latin America with the capacity of destabilizing state institutions are related to drug dealing that produces the economic resources for crime and guerilla recruitment. Drug trafficking is at the center of internal/external security links with the potential to disestablish continental security. Solutions should be related to social contexts and should be based both on security arrangements that respect human rights so as not to alienate the poor sectors of the population, and on the advancement of an active agenda for social inclusion. Thus we need to substitute the US government’s concept of terrorism with a more precise and useful typology of the different forms of violence and their sources – without denying, when applicable, the potential linkages with international terrorism.

The study of different forms of violence itself needs further research. The idea that violence (and even terrorism) is related to extreme poverty is both morally and empirically wrong. Many well-meaning people and organizations associate violence and poverty as a way to justify more social investment. But it stigmatizes the poor and is not based on empirical facts: a recent nationwide study by Viva Rio12 on armed violence indicates that the poorest sectors of society are not those most involved in violent criminal activities. Of course, contexts of social deprivation and exclusion produce the frustration and social basis for recruitment into and involvement in crime. However, more empirical research is needed to identify the specific groups most at-risk to engaging in armed violence (generally male youth) and policies to improve their chances in life, changing their malehood values and assuring inter-generational mobility

The same goes for the issues of “failing states” – a concept that has become common currency in the international arena, but is not widely discussed in the region. Latin Americans tend to (over)react to the concept of failing states, as they believe it may pave the way for foreign intervention. Their main argument is that history shows that most Latin American states, in spite of political crises and social upheavals, are solidly grounded. This argument is well-founded. However, it neither assures future results nor does it confront the issue that deterioration of the institutional system in some countries can generate political realities that may cause the United States itself to (over)react, destabilizing countries and creating failing states.

The problems of failing and collapsing states can not be dissociated from development issues and economic policies.13 At the same time, they are the product of more complex consequences of globalization: democratization of expectations, new identities which may become secessionist, and the breakdown of traditional local powers and hierarchies. One of the sources of Latin American states’ stability is their strong national identities and lack of open religious or ethnic conflicts. However, the latter may not continue to be the rule in some Andean countries where ethnic demands are mixed, although not reduced, to the economy. The last decades of political and cultural democratization – with the breakdown of clientelistic ties, individualization and the advancement of egalitarian values – have decreased tolerance toward government corruption especially in contexts where social inequality is increasingly unacceptable. This has paradoxically increased mistrust toward democratic institutions.

Latin American researchers could contribute with a more nuanced notion of “failing states” by highlighting processes through which states can begin to fail, but also how and where they find resources to maintain their stability. At the social research level, Latin America has a solid tradition of analyzing the complexities of state-building and violence. These analyses take institutional and social contexts into consideration, thus avoiding the oversimplification so common in the literature on international relations.

There was a period some years ago when international agencies actively supported reform of Latin American judiciary systems. During this period, much important research in this area was made available. The “fashion” seems to have passed and progress in this field has begun to lose momentum. Still, many of these studies did not incorporate functional analyses of security forces and small and light weapons use and control. Periodical reviews of the diverse Latin American experiences with police and judiciary reform would be fundamental to assure an effective and human rights-oriented system of law enforcement.

Latin American diplomacy in the last decade has made important gains, particularly in Central America. Yet research centers and NGOs working in these fields are still few. The same goes for early warning systems capable of relating internal conflicts and violence to their impact on democratic institutions and the effects of this internationally. We will need to overcome a tradition, still present in the social sciences and overwhelming in NGOs, of confusing analysis with denouncing abusive practices and analytical understanding with normative positioning.

Security sector reform will need to find solid support in the public debate and in civil society proposals. At the same time, it is important to recognize that civil society is not immune from criticism. Many civil society institutions have shown a defensive posture based on affirming idealistic principles while pitting themselves against and confronting the positions of legitimately constituted governments without offering alternative proposals and practical solutions. This posture leads to alienation from government bodies. Civil society cannot simply go against or denounce state practices, but should seek to work together with governments to democratize public institutions and the security sector through dialogue and partnerships.

Key questions for those working on human security issues in the region should include the following: How can we create a dialogue between the government and civil society around security issues? How can we expand the quantity and quality of work by non-governmental organizations to reduce violence and reform security sectors? How can we disseminate and exchange experiences, creating a forum of organizations in the region that work in this field?

Border issues and problematic regions is another field in which there is a lack of solid research. Weapons smuggling can’t be dissociated from piece-meal smuggling (in particular in the Triple Frontier region where thousands of persons trade goods from Paraguay into Brazil and Argentina on a daily basis) which is the main factor in corrupting border officials. Certain authors believe that some regions, particularly the Amazon, have become privileged spaces for trafficking weapons and drugs, and for the activities of armed groups. The legitimate concern with state sovereignty, especially Brazil’s for the Amazon, creates barriers for the development of collective security strategies and multilateral mechanisms. Further efforts should be made to improve customs controls and to advance the dialogue between researchers and NGOs working on security issues, border regions and human rights with the armed forces and the police.

1. On the history of the concept of human security, see Charles-Philippe David & Jean-François Rioux, “Le concept de securité humaine”, in Jean-François Rioux (ed.), La Securité Humaine(Paris: L’Harmattan, 2001).

2. On new forms of multilateralism, see the excellent review by Shepard Forman, New Coalitions for Global Governance: The Changing Dynamics of Multilateralism (Center on International Cooperation, 2004).

3. Available at: http://www.humansecurity-chs.org/finalreport/index.html. Last access on 15 September 2005.

4. For an updated presentation of the Canadian concept of human security and its role in foreign relations see: Ernie Regehr & Peter Whelan, Reshaping the Security Envelope: Defense Policy in a Human Security Context (Ploughshares Working Papers, 4-4, 2004). For more information on human security in general and the Canadian view in particular see: www.humansecuritygateway.com. Last access on 15 September 2005.

5. “A Human Security Doctrine for Europe”, the Barcelona Report of the Study Group on Europe’s Security Capabilities, presented to EU High Representative for Common Policy and Security Policy Javier Solana, Barcelona, 15 September 2004. Although the report has a more clear focus, it is unclear in its definition of what should be included within the notion of insecurity. In page 8 they refer to food, housing and health as possible candidates to be included in their definition of human security, although they indicate that “… their legal status is less elevated”.

6. A heterogeneous group of countries – Austria, Canada, Norway, Chile, Greece, Ireland, Jordan, Mali, Holland, Slovenia, Thailand and Switzerland (with South Africa as an observer member) – formed the Human Security Network in 2000, so far without much impact on the international scene.

7. For instance, the Brazilian National Public Security Secretariat website: http://www.segurancahumana.org.br/home.htm. Last access on 15 September 2005.

8. See various contributions in Jean-François Rioux (ed.), op. cit.

9. In a recent exhibit in New York organized by the DEA Museum, entitled Drug Traffickers, Terrorists and You, the concept of terrorism is broad enough to include a guerilla who killed an American officer in 1969 as a act of terrorism. The same exhibit on terrorism also included anti-smoking advertisements…

10. The Resolution of the Special Conference on Security (27-28 October 2003) in Mexico clearly reflects these impasses.

11. Today these are reduced to certain cases of historic “bad feelings”, for example between Chile and Bolivia, but the hypothesis of war has become practically excluded.

12. See www.vivario.org.br. Last access on 21 September 2005.

13. On this issue, see Susan L. Woodward, “The State Failure Agenda: From Sovereignty to Development”, MS 2004.