Reflecting on what drove the campaign and why it was so successful

Oxfam’s Behind the Brands campaign was launched in 2013 and sought to influence the sourcing policies of the world’s ten biggest food and beverage companies. Over the three years of Behind the Brands, the campaign achieved a series of significant successes, particularly around land rights, women’s empowerment and climate change, both in mobilising a significant number of supporters and achieving a series of significant policy wins. This article highlights some of the principles and tools the campaign used in achieving those policy wins.

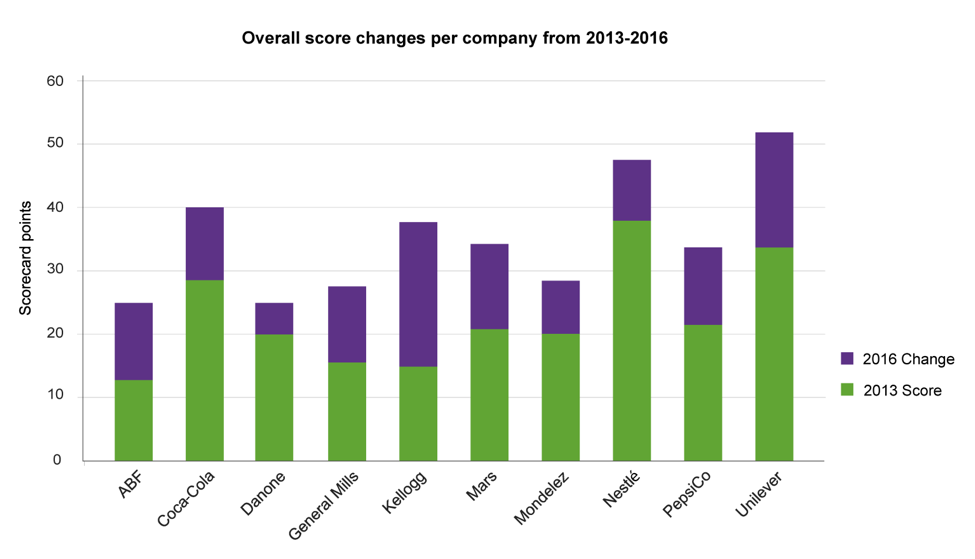

Oxfam’s Behind the Brands campaign was launched in 2013 and sought to influence the sourcing policies of the world’s ten biggest food and beverage companies, the Big 10.11. The ten companies were Associated British Foods (ABF), The Coca-Cola Company, Danone, General Mills, Kellogg, Mars, Mondelez, Nestle, PepsiCo, and Unilever. The targets of the campaign were food and beverage companies with highly recognisable global brands, but the indirect targets of the campaign were food commodity traders. In 2012 Oxfam published Cereal Secrets, which looked at the top four commodity traders at the time, Archer Daniel Midland, Bunge, Cargill and Louis Dreyfus (known as the ABCDs due to their initials) and their dominance in certain commodities along with their impact on global agricultural issues, including the lives of smallholder farmers. One aspect of this report focused on how invisible the traders are in policy debates, their lack of transparency as companies and absence of any brand which would provide them with a public profile. On the other hand, the food and beverage companies, whose brand success is driven by its emotional connection to the public – are directly accountable to consumers concerned about social and environmental impacts of agriculture.

In order to tap into the brand connection felt by consumers, Oxfam launched the Behind the Brands campaign with the dual goal of building a movement of global supporters and achieving specific improvements in the sustainability policies of the Big 10. Behind the Brands adopted a theory of change which assumed that less visible supply chain actors, like the commodity traders, could be pressured by big consumer brands which are vulnerable to public pressure.

By calling on these big brands to take on progressive policies and to implement them upstream in their supply chains Oxfam assumed that systemic change could happen across supply chains. The campaign approach brought together several components to create pressure on the companies to make commitments:

While Oxfam looked at seven themes in the scorecard relating to agricultural sourcing, the public campaign highlighted three issues over the three years; women, land and climate change. Oxfam first highlighted the issue of women in cocoa supply chains of the large chocolate companies. Women cocoa farmers are central to the sustainability of the cocoa supply chain and cocoa-growing communities. Too often unrecognised and under-valued, women’s labour makes significant contributions to the amount of cocoa produced, which is under increasing demand. Empowering women cocoa farmers not only has a positive impact on the lives of women, men and communities, but also has a business advantage. When women have control over their own income or family earnings, they reinvest in their families, children and communities, increasing the well-being and the sustainability of cocoa-growing communities.33. “Mars, Mondelez and Nestle and the Fight for Women’s Rights,” Oxfam Media Briefing, February 26, 2013, accessed June 7, 2017, https://www.oxfam.ca/sites/default/files/imce/btb-gender-media-briefing.pdf.

On land, Oxfam highlighted risks and impacts on communities related to land rights in the sugar supply chains of some of the food and beverage companies. Oxfam showcased three cases where communities living off the land had been denied their land rights in favour of sugar mills that were also suppliers to some of the Big 10 companies. Land governance is weak in many countries, and often favours corporate interests over the rights of local farmers and communities. Governments have a pivotal role to play in protecting rights through legislation and enforcement but the campaign sought to show companies purchasing commodities that they could also ensure that land rights are respected with their suppliers.44. “Sugar Rush: Land Rights and the Supply Chains of the Biggest Food and Beverage Companies,” Oxfam, October 2, 2013, accessed June 7, 2017, https://www.oxfam.org/sites/www.oxfam.org/files/file_attachments/bn-sugar-rush-land-supply-chains-food-beverage-companies-021013-es_1_0.pdf.

Finally, Oxfam produced data that showed that the agricultural emissions of the Big 10 were equivalent to the emissions of the 25th most polluting country. In highlighting this new data and connecting it to the stories of men and women farmers already dealing with climate change, Oxfam challenged companies to take responsibility for the agricultural emissions within their supply chain and be an advocate for progressive climate change policy.55. “Standing on the Sidelines: Why Food and Beverage Companies Must Do More to Tackle Climate Change,” Oxfam, May 19, 2014, accessed June 7, 2017, https://www.oxfamamerica.org/explore/research-publications/standing-on-the-sidelines/.

Over the three years66. See, “The Journey to Sustainable Food; A Three-Year Update on the Behind the Brands Campaign,” Oxfam, April 19, 2016, accessed June 7, 2017, https://www.oxfam.org/en/research/journey-sustainable-food-three-year-update-behind-brands-campaign. of Behind the Brands, the campaign achieved a series of significant successes, particularly around land rights, women’s empowerment and climate change, both in mobilising a significant number of supporters and achieving a series of significant policy wins:77. “Celebrating three years of Behind the Brands,” Youtube video, 1:36, posted by oxfaminternational, April 19, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z1P2oGG569A.

The campaign used a combination of tactics and approaches to gain corporate commitments. It sought to walk a moderate line: hard hitting enough to convey urgency so supporters will act while at the same time not so aggressive as to create strained relationships with companies that could not be repaired. The Oxfam formula for the Behind the Brands campaign was multi-faceted.

Oxfam combined evidenced-based advocacy using deep company engagement, combined with digital mobilisation, media, offline and online stunts, advertising, investor and shareholder activism, case studies, and collaboration with allies and influencers. The evidence-based advocacy on Behind the Brands always included a justification of why specific companies were targeted along with a business case that highlighted best practice.

In addition, Oxfam took a “critical friend” approach on Behind the Brands. Many corporate campaigns personalise a company through the chief executive officer or other decision-maker; they may call for boycotts or generally paint the company as inherently bad. Oxfam, on the other hand, did not call for boycotts because the impact is generally felt by the communities for whom Oxfam was advocating (e.g., farmers and workers). Rather, Behind the Brands has taken the approach that the private sector can be a positive actor for development. In garnering several commitments on the campaign, Oxfam also took into account the fact that it would work with a company on implementing those commitments not only as a watchdog to ensure that they follow through but also as an advisor on how best to do it. Aggressive campaigns can mean a real hangover after the celebration of a win. After all, at the end of the day relationships between Oxfam and the company sit with individuals and when there are hard feelings between those individuals it makes it challenging to work together, even on shared outcomes and interests.

So, what’s the Behind the Brands code for corporate-campaigning?

Of course there are also challenges with this private sector influencing approach:

Behind the Brands gave Oxfam relatively quick wins with its targets, built a movement with several hundred thousand supporters, and provided a foundation for building out programmatic work that will track the implementation of the commitments made by the companies throughout the campaign. At the same time, Oxfam’s approach in Behind the Brands is one which required a huge amount of resources, particularly in staff time. It also meant for complicated ways of working as the team was global in nature and conducting company engagement in multiple markets which needed to be tightly coordinated. Nevertheless, the approach used could be modified for much smaller campaigns, including one that focused on fewer companies and markets.