An overview of latest developments and how to improve a key mechanism in human rights protection

The United Nations (UN) Committee against torture (CAT) recently adopted an innovative system to follow up, assess and grade the implementation of its recommendations to States. The new follow-up procedure largely draws on the precedent established by the UN Human Rights Committee, although it is also more comprehensive. It offers a range of new opportunities for human rights defenders and practitioners both to increase the visibility on the implementation of CAT recommendations, as well as encouraging States parties to do more to comply with those recommendations. The CAT and the Human Rights Committee now stand at the forefront of an emerging trend of improved assessment of the implementation of UN human rights bodies’ recommendations. Despite the formidable potential which the evaluation and grading system provides, much remains to be done to make the most of them. They need to be better promoted and disseminated to a broad range of actors. They should also be harmonised and made more accessible.

United Nations (UN) human rights treaty monitoring bodies regularly pledge to improve the way they follow up on their recommendations (or “Concluding Observations” as per UN terminology) to States.22. See for example, “The Poznan Statement on the Reforms of the UN Human Rights Treaty Body System,” International Seminar of Experts on the Reforms of the United Nations Human Rights Treaty Body System, Sept. 28-29, 2010, §25-31, accessed May 21, 2017, http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/HRTD/docs/PoznanStatement.pdf; or “Implementation of Human Rights Instruments,” UN Doc A/71/270, 2016, accessed May 21, 2017, http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CHAIRPERSONS/Shared%20Documents/1_Global/A_71_270_25154_E.docx. Civil society actors also regularly call and encourage treaty bodies to improve the way they support and track the implementation of these recommendations.33. See for example, “Joint NGO Statement. 2015 Annual Treaty Body Chairpersons Meeting, 22-26 June, 2015, San José,” Coalition of NGOs, §B, December 26, 2015, accessed May 21, 2017, http://goo.gl/jge5Qv.

The rhetoric on the need to improve the follow-up, evaluation and impact of the recommendations of UN human rights bodies is widespread and largely accepted. Yet what is required to transform discourse into facts is literally a paradigm shift. The UN human rights machinery and its governmental and non-governmental allies and counterparts need to radically rebalance their efforts and focus more on implementation and assessment and less on formulation of resolutions and recommendations.

Recommendations from Treaty Bodies (TBs) receive primary attention from both the drafters and their lobbyists at the stage of formulation, rather than on their actual implementation. The level of competition between human rights experts, diplomats, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), national human rights institutions (NHRIs) and lobbyists is quite high in terms of the formulation of recommendations, and these different actors compete to ensure that their issues of concern will be properly reflected in the recommendations. Yet similar efforts are very seldom taken to verify the level of implementation of these resolutions on the ground. The paradigm shift required to rebalance formulation with implementation and evaluation could involve UN TBs formulating less recommendations and instead dedicating more resources to assessing the evaluation of previous recommendations, and disseminating the results of their evaluation. The elaborate follow-up and grading systems adopted in recent years by several UN TBs, and the related score cards or grades reflecting the TBs’ assessment of the level of implementation of recommendations, provides a unique and remarkable exception in the current context of overwhelming absence of visibility on implementation of UN resolutions and recommendations.

The system was mainly pioneered by the UN Human Rights Committee (HR Ctte), which focuses on the level of compliance with some of its recommendations 12 to 18 months following the review of States parties. This innovative and effective system has been replicated and even improved by the Committee against torture (CAT) (see section 4 below). The TB system also provides valuable opportunities to “bring recommendations home” as part of follow-up visits in reviewed countries, as detailed in two specific case studies below.

In 2013, the UN HR Ctte, the body that monitors the implementation of the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), was the first UN TB to adopt an elaborate system to follow-up and track the level of implementation on some of its recommendations (maximum four) to States.44. "Note by the Human Rights Committee on the procedure for follow-up to concluding observations," UN Doc CCPR/C/108/2, United Nations, October 21, 2013, accessed May 21, 2017, http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=CCPR%2FC%2F108%2F2&Lang=en.

The procedure codified a practice which the Committee initiated in 2012.55. The first HR Ctte follow up report which mentioned grades on recommendations was adopted during the 104th session in March 2012 (UN Doc CCPR/C/104/2). The grades mentioned in the report were slightly distinct from the grades codified in the 2013 procedure. For instance, they did not include a grade E. Additional simplifications were brought to the grades during the 119th session in March 2017, see “Human Rights Committee discusses progress reports on Follow-Up to Views and on Follow-Up to Concluding Observations,” The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), March 20, 2017, accessed May 21, 2017, https://goo.gl/KuIrUY. It is based on a simple scale of grades ranging from A to E, reflecting the best level of implementation for a recommendation (grade A) to the worst level (grade E). The grades are adopted by the Committee on the basis of information provided by the State party and other actors, notably civil society or NHRIs. Contributions to the Committee’s follow-up reviews are expected 12 months after the review of periodic reports, based on the two to four recommendations which the Committee identified as requiring priority attention.66. CCPR/C/108/2, § 6&7. These two to four recommendations need to be implemented by the State party within the 12 months after the review of periodic reports, as opposed to other recommendations for which a longer timeframe is provided (around four years generally77. Longer lapses for the subsequent State periodic report are provided by the Committee in countries where implementation of the ICCPR is seen as less problematic. Shorter lapses are given to States which seemingly encounter more problems in implementing the ICCPR.). The 12 months’ timeframe, which is relatively short to implement important and often difficult recommendations, is nonetheless suitable to encourage States parties to focus their efforts and prioritise them in the year following reviews in Geneva. Such prioritisation schemes are not unique to the UN Human Rights Ctte, and four other treaty monitoring bodies have adopted similar procedures to prioritise the implementation of some recommendations.88. These are the Committee Against Torture, Committee for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, Committee for the Elimination of Discrimination against Women and Committee on Enforced Disappearances.

A Special Rapporteur for follow-up on concluding observations and a Deputy are elected amongst HR Ctte members. They are in charge of preparing draft evaluation reports and grades on the basis of information provided by the State party on follow-up, 12 months after the review. The draft evaluation report and the grades reflecting the level of implementation are discussed and adopted in plenary during public sessions of the Committee. The Committee’s follow-up reports and grades are available on its website.99. “The Treaty Body Database,” The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), accessed May 21, 2017, http://goo.gl/vXPK5H. Additionally, the Committee’s Secretariat regularly updates and publishes a global overview on the status of States parties under the follow-up.1010. “Follow-up to concluding observations - International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights,” The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), accessed May 21, 2017, http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/TreatyBodyExternal/FollowUp.aspx?Treaty=CCPR&Lang=en. The Centre for Civil and Political Rights, a Geneva based NGO which played a leading role in the adoption of the procedure,1111. CCPR/C/108/2, §17. publishes overviews of the Committee grades on its website after each Committee session.1212. E.g. see “Latest Assessment on the Implementation of HR Committee Recommendations,” Centre for Civil and Political Rights, 2017, accessed May 21, 2017, http://conta.cc/2mJTfCm. The Centre has also supported the preparation and submission of civil society follow up reports in over 30 countries worldwide.1313. Available on the CCPR Centre’s website, www.ccprcentre.org. An FAQ (CCPR Centre 2016) on the HR Ctte’s follow-up and grading system is also available on the Centre’s website.1414. “Follow Up and Assessment,” CCPR, accessed May 21, 2017, http://ccprcentre.org/follow-up-and-assessment

The detailed criteria or grades1515. CCPR/C/108/2, §17. used by the HR Ctte are as follows:

| Reply/action satisfactory | |

| A | Reply largely satisfactory |

| Reply/action partially satisfactory | |

| B1 | Substantive action taken, but additional information required |

| B2 | Initial action taken, but additional information required |

| Reply/action not satisfactory | |

| C1 | Reply received but actions taken do not implement the recommendation |

| C2 | Reply received but not relevant to the recommendation |

| No cooperation with the Committee | |

| D1 | No reply to one or more of the follow-up recommendations or part of a follow-up recommendation |

| D2 | No reply received after reminder(s) |

| The measures taken are contrary to the recommendations of the Committee | |

| E | The reply indicates that the measures taken go against the recommendations of the Committee |

Thanks to the HR Ctte’s innovative approach, more than 65 countries from all world regions have been assessed on their level of compliance with the Committee’s priority recommendations. Examples of grades A, which reflect the full implementation of the recommendation, can be found in countries such as Mongolia (on the reform of the criminal justice system1616. "Report of the Special Rapporteur for follow-up on concluding observations of the Human Rights Committee (106th session, October 2012)," UN Doc CCPR/C/106/2, CCPR, November 13. 2002, accessed May 21, 2017, http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=CCPR%2FC%2F106%2F2&Lang=en.) or Angola (on the universal registration of child birth1717. "Report on follow-up to the concluding observations of the Human Rights Committee," UN Doc CCPR/C/112/2 , CCPR, December 8, 2014, accessed May 21, 2017, http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=CCPR%2FC%2F112%2F2&Lang=en.). Likewise, a grade E has also been adopted by the Committee when Indonesia undertook a range of executions of individuals sentenced to the death penalty for drug crimes, in contradiction with the HR Ctte’s recommendation,1818. "Report on follow-up to the concluding observations of the Human Rights Committee," UN Doc CCPR/C/113/2, CCPR, May 27, 2015, accessed May 21, 2017, http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=CCPR%2FC%2F113%2F2&Lang=en. or when Colombia enacted a reform of the military justice system which was deemed contrary to the HR Ctte’s recommendation to have civil courts investigate violations committed by the armed forces.1919. "Report of the Special Rapporteur for follow-up on concluding observations of the Human Rights Committee (107th session, 11–28 March 2013)," UN Doc CCPR/C/107/2, CCPR, April 30, 2013, accessed May 21, 2017, http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=CCPR%2FC%2F107%2F2&Lang=en.

The grades adopted by the HR Ctte since 2013 constitute a growing body of evidence on the impact of the recommendations at the national level. The HR Ctte follow-up reports and the grades, although hardly accessible, give a unique visibility on the efforts of governments and other actors to comply with the Committee’s recommendations. They also provides a growing body of statistical data and empirical evidence which are of direct and primary relevance for the “scholarly neglect[ed]” study of the domestic impact of UN treaty body recommendations.2020. Jasper Krommendijk, "The Domestic Effectiveness of International Human Rights Monitoring in Established Democracies. The Case of the UN Human Rights Treaty Bodies,” The Review of International Organizations 10, no. 4 (Dec. 2015): 1-24. As such, the system has a potential to improve substantially the way we can study and understand the implementation of HR Ctte recommendations and their impact.

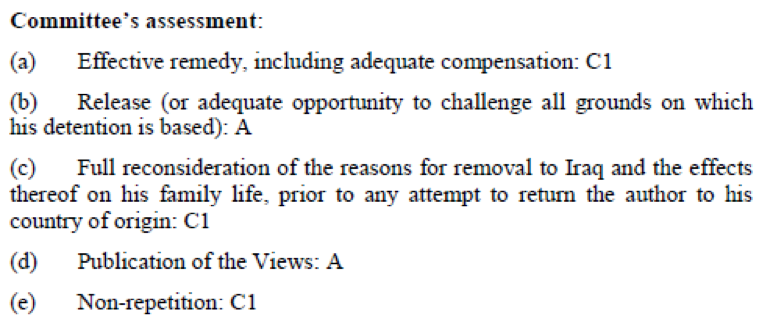

The grading system is also used by the HR Ctte to follow up on state compliance with its views related to individual complaints (or “Communications” as per UN terminology). In States which have ratified the First Optional Protocol to the ICCPR, individual complaints may be brought to the HR Ctte’s attention. The views subsequently adopted by the HR Ctte are transmitted to States and, as with recommendations to States parties, the HR Ctte uses the same set of grades to reflect the level of enactment of its views on individual complaints by States parties.

Example of the Committee grades adopted on the case Al Gertani VS Bosnia and Herzegovina during the 113th session of the HR Ctte (March-April 2015). CCPR/C/113/3. P. 6.

The HR Ctte follow-up reports on individual communications are available on the webpages of the sessions2121. “Sessions for CCPR - International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights,” CCPR, accessed May 21, 2017, http://goo.gl/tHuUQl. during which they were adopted. In addition to the complainant and the defendant, third parties such as NGOs can submit contributions to the HR Ctte on measures taken by States parties to comply with HR Ctte views. On follow-up to views the Rapporteur may request meetings with representatives from States parties.

Although the majority of HR Ctte views on individual complaints are not adequately followed or enacted by States parties, positive examples of implementation can be found in several cases. For instance, the HR Ctte found in 2015 that Australia had fully complied with three out of four of its views with regards to the case “Horvath”2222. “Communication No. 1885/2009,” Federation of Community Legal Centres, July 2, 2010, accessed May 21, 2017, http://www.communitylaw.org.au/flemingtonkensington/cb_pages/images/Reply%20to%20the%20Australian%20Government.pdf. and adopted grade A for these three views (CCPR/C/113/3):

Other examples of initial or substantial action taken with regards to HR Ctte views can be found in various countries from the Global South (e.g. in Maharjan VS Nepal2323. Case 1863/2009, as assessed in report “Follow-up Progress Report on Individual Communications, Adopted by the Committee at its 112th Session (7–31 October 2014),” CCPR/C/112/3, CCPR, December 16, 2014, accessed May 21, 2017, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G14/244/45/PDF/G1424445.pdf?OpenElement.).

As stated by Joseph,2424. Sarah Joseph, Katie Mitchell, Linda Gyorki, and Carin Benninger-Budel, Seeking Remedies for Torture Victims. A Handbook on the Individual Complaints Procedures of the UN Treaty Bodies (Geneva: World Organization against Torture, 2014): 96. the grading system on individual complaints “serves to place sustained pressure on recalcitrant States.” As with the implementation of Committee recommendations, the use of grades for all individual complaints addressed by TBs would considerably improve the visibility on the level of implementation of the HR Ctte views at the national level. Yet the grades on follow-up to HR Ctte views suffer from the same lack of attention and dissemination as the grades on recommendations to States parties. It is not possible for individuals, without a sound knowledge of the procedure and the Committee, to access the information about the grading system, and the adopted grades themselves.

Despite the above-mentioned opportunities provided by the HR Ctte’s follow-up system on both recommendations and views, it still remains poorly known and underused by human rights actors and activists. Although the follow-up reviews of countries like the United States of America (US)2525. E.g. see Sarah Lazare, “UN Report Card Gives US ’Failing Grade’ on Human Rights.” Common Dreams, July 30, 2015, accessed May 21, 2017, http://www.commondreams.org/news/2015/07/30/un-report-card-gives-us-failing-grade-human-rights. or Hong Kong2626. E.g. see “UN Rights Panel Calls for Open Elections in Hong Kong,” View HK, October 24, 2014, accessed May 21, 2017, https://viewhk.blogspot.com.br/2014/10/un-rights-panel-calls-for-open.html. (China) have received substantial attention, many human rights actors still either do not know, or do not use the follow up system (or both). Civil society actors and NHRIs, for example, can provide information and they can even suggest grades on their own assessment of the level of implementation of the Committee’s recommendations. As evidenced in the Committee’s follow-up reports, these contributions are vital sources of information for the Committee’s follow up work. Much remains to be done in outreach, capacity strengthening and research to use the Committee’s follow up procedure to its full potential.

The most stringent limitation currently affecting the HR Ctte follow up procedure relates to its lack of suitable visibility, and the limited efforts to disseminate the grades adopted by the Committee. Currently, the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), which acts as the Secretariat of the Human Rights Committee, does not undertake any outreach activity specifically related to the grades adopted by Treaty Bodies. The adoption of the follow-up reports are not mentioned alongside country reviews and other ordinary tasks of the Ctte in regular OHCHR mailings and advertisements (e.g. see end of session news2727. "UN Human Rights Committee publishes findings on South Africa, Namibia, Sweden, New Zealand, Slovenia, Costa Rica, Rwanda," The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), March 30, 2016, accessed May 21, 2017, http://www.ohchr.org/en/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=18541&LangID=E.). In fact, the grades only appear in the details of the follow-up reports, which themselves can only be found by those who are more familiar with the Ctte’s working methods (see below example).

Example of the Committee grades adopted on Chile during the 104th session of the HR Ctte (March 2012). CCPR/C/104/2. P.3.

Neither the Committee nor the OHCHR make a statement when the follow up reports are issued, nor are they circulated proactively to relevant stakeholders. The reports are made available on the webpages of each Committee session once they are adopted (currently, this means on average two to six months after the end of each session, e.g. see the webpage of the 116th session2828. CCPR - International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, accessed May 21, 2017, http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/treatybodyexternal/SessionDetails1.aspx?SessionID=1016&Lang=en.).

The justifications for this current lack of visibility can be partially put down to different factors, including lack of will and competing priorities for key actors in the system, notably the Secretariat, as well as a limited outreach capacity in the Secretariat.

Enhancing the visibility of the HR Ctte’s follow-up and grading system would not only contribute to boosting the level of implementation of the recommendations. Given that treaty bodies have been chronically under-resourced, it could also entail additional spin offs such as increasing public and financial support to their work.2929. Vincent Ploton, “Addressing the Critical Funding Gap at the UN Human Rights Office.” Oxford Human Rights Hub blog, December 6, 2014, accessed May 21, 2017, http://goo.gl/Ew6kcQ.

The grades adopted by the HR Ctte provide an authoritative evaluation of the implementation of a major international human rights law standard by a quasi-judicial body. Within the UN alone, both the grades on recommendations and on complaints are currently not reflected but could be:

Additionally, the grades adopted on the follow-up to individual complaints provide a relevant indication about States’ capacity and/or willingness to comply with the views from the body charged with the interpretation of the ICCPR. As such, the grades on complaints could be reflected in the proceedings of regional and national courts, as one of the elements of the treaty body’s jurisprudence.

The grading system pioneered by the Human Rights Ctte has so far partially been replicated by the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD)3131. http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/TreatyBodyExternal/FollowUp.aspx?Treaty=CRPD&Lang=en accessed June 9, 2017. and the Committee on Enforced Disappearances (CED3232. “Report on follow-up to concluding observations of the Committee on Enforced Disappearances (7th session, 15-26 September 2014),” UN Doc CED/C/7/2, CED, October 28, 2014, accessed May 21, 2017, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G14/193/35/PDF/G1419335.pdf?OpenElement.). The Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) uses a simpler assessment system3333. http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CEDAW/Shared%20Documents/1_Global/INT_CEDAW_FGD_7102_E.pdf, accessed June 9, 2017. based on the following four categories:

All of the current treaty body grading systems are based on some of the recommendations to States, not all. The adoption by these three treaty bodies of elaborate procedures to foster the implementation of recommendations and/or views is certainly welcome. Yet they bear a similar potential for development and similar challenges to those listed above on the HR Ctte. Namely, these procedures, which are still relatively new, will need to better trickle down to the grass roots and to human rights defenders and practitioners. Several actors, including NGOs and some treaty bodies themselves regularly encourage (e.g. Poznan statement3434. Ibid. § 27, 2016 meeting of treaty body chairs3535. Ibid.) those treaty bodies which do not yet have follow-up procedures to adopt one, and/or to harmonize the different existing procedures. Most recently, the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights adopted a follow-up procedure3636. http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/CESCR/Follow-upConcludingObservations.docx accessed June 27, 2017. which establishes yet a new set of treaty body assessment grades on the implementation of recommendations: “sufficient progress”, “insufficient progress”, “lack of sufficient information to make an assessment” or “no response”.

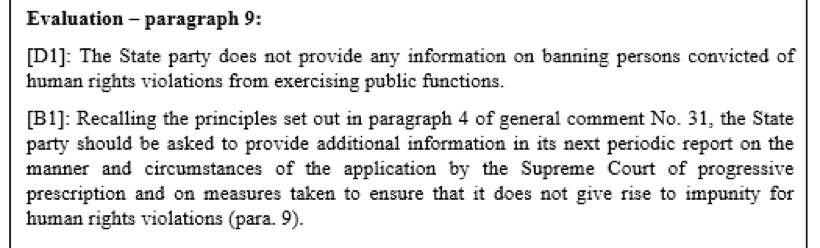

The follow-up and grading procedure3737. "Guidelines for Follow-up to Concluding Observations," UN Doc. CAT/C/55/3, CAT, September 17, 2015, accessed May 21, 2017, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G15/210/35/PDF/G1521035.pdf?OpenElement. recently adopted by the CAT not only builds on the positive and effective elements of the preceding HR Ctte procedure. It also integrates innovative elements which address some of the above mentioned existing challenges encountered with the HR Ctte procedure. It is focused on Concluding Observations and, according to the main architect of this new procedure Jens Modvig,3838. Verbal exchanges with the author, 27 November 2015. Jens Modvig was the CAT Rapporteur on follow up at the time when the procedure was established, and he was elected as the Chair in April 2016. there are no plans for such a grading system to be adopted for follow-up to individual complaints to the CAT.

To counter some of the challenge noted above about the Human Rights Ctte, the CAT procedure integrates three different sets of grades:

Therefore, the CAT’s new procedure will tackle the need to differentiate between the actions taken by States to comply with recommendations, and the way they report back to the Committee. But even more importantly, the CAT’s new procedure is also tackling the issue of recommendations which are not flagged as requiring priority attention within the 12 months after the reviews in Geneva. By encouraging States to come up with implementation plans for these recommendations, the CAT has found a creative and effective way to foster the implementation of its recommendations. Without creating a new obligation on States (the procedure “encourages” States to follow that route), this new development is likely to contribute at least to give more visibility on steps taken at the national level following reviews to comply with recommendations.

Finally, the new CAT procedure also drew inspiration from the HR Ctte procedure on two useful points:

As detailed in the above sections, the follow up procedures adopted by the HR Ctte, CAT and other treaty bodies offer, broadly speaking, two opportunities for human rights defenders:

The TB follow-up procedures offer considerably more opportunities than risks for human rights defenders. One notable exception concerns threats and reprisals. The UN has considerably improved its institutional response to reprisals and threats against individuals cooperating with its human rights bodies, for instance with the adoption by TBs of the San José Guidelines in 2015.3939. “Guidelines against Intimidation or Reprisals (‘San José Guidelines’),” UN Doc. HRI/MC/2015/6, HRI, July 30, 2015, accessed May 21, 2017, http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=HRI/MC/2015/6&Lang=en. Yet it should remain an individual decision of human rights defenders as to whether contributing to the follow-up procedures, and particularly suggesting grades and commentaries on the level of implementation of recommendations, could put them at risk of reprisal.

One of the strengths of the HR Ctte’s procedure on follow-up to recommendations is that it has been used by Committee members as part of several follow-up visits to States parties after the reviews in Geneva. These non-official field visits, almost all of which have been organised by the Centre for Civil and Political Rights (CCPR Centre) (e.g. in Angola,4040. “Direitos Humanos: ONU Assinala Avanços e Recuos em Angola,” AGORA, 2014, accessed May 21, 2017, http://goo.gl/EYng5K. Cambodia,4141. Charles Rollet and Vong Sokheng, “Rights review process ‘has little NGO input’.” The Phnom Penh Post, August 27, 2015, accessed May 21, 2017, http://goo.gl/Abe6Mt. Indonesia,4242. Hans Nicholas Jong, “UN Presses Indonesia on Human Rights Progress Report,” The Jakarta Post, January 17, 2015, accessed May 21, 2017, http://goo.gl/fo3HNn. Mauritania4343. "Création d’un Collectif d’ONGs pour le Suivi des Recommandations des Mécanismes Onusiens de Droits de l’Homme en Mauritanie," CRIDEM, August 30, 2014, accessed May 21, 2017, http://goo.gl/yiUXIf. or Namibia4444. “Human Rights Committee Members Concerned about Discrimination and Gender-based Violence in Namibia,” CCPR Centre, 2016, accessed May 21, 2017, http://goo.gl/YOFM84.), have made a significant difference. The visits have continued the constructive dialogue initiated with States during the reviews including meetings with key national decision makers, reaching out to relevant stakeholders, and contributing to the dissemination of recommendations. These visits also play a key role in explaining the treaty bodies’ follow-up and assessment procedure, and encourage both governmental and non-governmental actors to take advantage of the important opportunities provided by the system. As TBs have acknowledged (e.g. Poznan statement §28), field visits at the national level following reviews of States parties in Geneva have proved to be an effective way to maintain this dialogue. Following one such visit to Nepal, one HR Ctte member said: “It was eye opening for me to be able to discuss with government stakeholders, and meet with a much broader range of relevant actors than those we normally get to interact with in Geneva.”4545. Quoted in “UN Human Rights Committee. Participation in the reporting process. Guidelines for NGOs,” CCPR Centre, 2015, p. 19, accessed September 9, 2016, http://goo.gl/kyGPF5.

The author was involved in a CCPR Centre-organised high-level follow up visit to Mozambique in December 2014, which was headed by the former HR Ctte Chair Ms. Zonke Majodina (South Africa). The visit followed the first ever review of Mozambique by that Committee in October 2013. The HR Ctte had issued urgent recommendations4646. “Concluding Observations on the Initial Report of Mozambique,” UN Doc. CCPR/C/MOZ/CO/1, CCPR, November 19, 2013, accessed May 21, 2017, http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=CCPR/C/MOZ/CO/1&Lang=En. on arbitrary arrest and detention, conditions of detention and the need to increase the number of judges. During the follow-up visit, the delegation was able to meet with a range of high-level government and international officials, including the Minister of Justice who had been the head of the government delegation during the review by the HR Ctte in Geneva. Quite clearly, the CCPR Centre delegation would not have been able to have access to these individuals if it had not been headed by a former Chair of the HR Ctte whom in this case, was a national of a neighbouring and relatively friendly country. The meeting with the head of the government delegation in Maputo was instrumental for the CCPR Centre delegation to gauge progress made on the implementation of the urgent recommendations. Although the author’s government interlocutors in Mozambique were at best vaguely familiar with the follow-up and grading procedure of the Committee, there was nonetheless more interest than defiance. Meetings with government interlocutors also elicited that Mozambique had elaborate plans to follow up on the Universal Periodic Review recommendations. Nonetheless, there were no such plans for follow-up to treaty body recommendations.

The main goals of the high-level follow-up visit were to remind government officials about the recommendations of the HR Ctte, gauge progress achieved towards their realisation, and encourage both state and non-state actors to submit follow-up reports to the HR Ctte. The visit to Maputo was instrumental in achieving these objectives. Following the visit, continued and sustained follow-up initiatives were undertaken by the CCPR Centre (through bilateral contacts with state officials) and the HR Ctte (through formal and informal contacts with the Permanent Mission of Mozambique in Geneva) to convince the government to submit their follow-up report,4747. “Response to Concerns Raised in Paragraphs 13, 14 and 15 of the Recommendations Made by the Human Rights Committee Following the Examination of the Government of Mozambique During its 109th Session,” Permanent Mission of the Republic of Mozambique to the United Nations Office in Geneva, Nov. 23, 2015, accessed May 21, 2017, https://goo.gl/Vq0jDT. which they finally did in November 2015. In parallel, the coalition of civil society organisations which the CCPR Centre had engaged with prior, during and after the first review of Mozambique by the HR Ctte were able to submit their own assessment4848. “Mozambique Follow Up Report to Human Rights Committee,” Coalition of Mozambique NGOs with support from CCPR Centre, March 2015, accessed May 21, 2017, http://goo.gl/sd7W7f. on the level of implementation of the Ctte’s recommendations. At the time of writing, the Committee were planning to review both government and NGO follow-up inputs at the 188th session (October-November 2016) which is when they will adopt the grades reflecting the level of implementation of the recommendations.

The author was also involved in a CCPR Centre-organised high-level follow up visit to Mauritania in August 2014. HR Ctte expert Lezhari Bouzid from Algeria, who had been the country Rapporteur for the review of Mauritania in October 2013, led the delegation which was organised and funded by the CCPR Centre. On this occasion, Lezhari Bouzid and the author were able to meet with a range of government representatives including the Ministers of Justice and Interior, National Commissioner on Human Rights, OHCHR and other UN offices, diplomatic missions, the NHRI and NGOs. The delegation was also able to meet with representatives from the Inter-Ministerial delegation on human rights, which held the formal responsibility to report and follow up on treaty body recommendations under the auspices of the National Commissioner for Human Rights. The series of meetings and workshops with national counterparts proved to be instrumental in raising awareness and disseminating the recommendations adopted by the Committee less than a year before in Geneva. However, the visit also enabled the CCPR Centre delegation to gain a good overview of the steps that had been taken (or not taken) towards complying with the four urgent recommendations which related to:

Almost all of the delegation interlocutors had either never heard of the HR Ctte’s follow-up and assessment system, or they knew little about it. However, in most cases, the delegation’s interlocutors were quite curious, and most were willing to contribute to the process to the extent they could. During the visit, the National Commissioner for Human Rights pledged to submit the follow-up report4949. “Rapport Interimaire de Suivi Relatif a la Mise en Oeuvre des Recommandations Prioritaires du Comite des Droits de L’home,” UN Treaty Body Database, OHCHR, 2014, accessed May 21, 2017, https://goo.gl/YaHGoS. due one year after the review on time, which they did in November 2014. This, together with the submission of a report by a coalition of Mauritanian NGOs5050. "Mauritanie: Rapport de Suivi des Observations Finales du Comité DH," CCPR Centre, October. 2014, accessed September 21, 2016, https://goo.gl/liCa87. supported by the CCPR Centre, enabled the Committee to undertake a formal assessment of the level of implementation of their four priority recommendations. During the 113th session of the HR Ctte, held in March 2015, the following grades5151. Follow up letter sent to Mauritania. Human Rights Committee. April 13, 2015, accessed May 21, 2017, https://goo.gl/gyJ8iw. were adopted:

What is particularly interesting and telling in the Mauritania example is that the government maintained a high level of compliance with the HR Ctte following the publication of the grades, and submitted a new report in May 2015,5252. “Concluding Observations on the Initial Report of Mauritania,” UN Doc CCPR/C/MRT/CO/1/Add.1, CCPR, May 8, 2015, accessed May 21, 2017, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G15/092/30/PDF/G1509230.pdf?OpenElement. which subsequently enabled the HR Ctte to review the first set of grades they had adopted, and adopt a new set of updated grades5353. Follow up letter sent to Mauritania. Human Rights Committee. April 15, 2016, accessed May 21, 2017, https://goo.gl/JeugaF. in March 2016. This evidences what the delegation and the author perceived during the follow-up visit to Mauritania, i.e. that government counterparts were interested in the grading system and willing to contribute to it, with the obvious hope that the Committee would acknowledge the efforts taken towards complying with the recommendations. The implementation of urgent HR Ctte recommendations in Mauritania and their evaluation, which was still ongoing at the time of writing, constitute an interesting process given that both governmental and non-governmental actors contributed to the process in good faith. This enabled the HR Ctte to adopt grades which acknowledged steps taken, while requesting more to be done towards full compliance.

As highlighted in the above sections, the innovative follow-up and grading systems developed by treaty bodies constitute an important breakthrough in the overwhelmingly accepted desire to improve the implementation of UN human rights recommendations. Key elements of a robust follow-up and grading system include, inter alia: the need for a transparent, thorough and clear methodology; buy-in and acceptance from a wide range of relevant stakeholders; expert and independent assessment; widespread dissemination and differentiation between substance and form. Much remains to be done to strengthen, streamline, highlight and replicate the existing procedures within treaty bodies themselves. The ongoing process of TB strengthening provides a suitable avenue to do so. As it has been previously argued5454. The High Commissioner’s “ability to strengthen treaty bodies in a meaningful way will be a key determinant of his tenure”. In Vincent Ploton, “More Ambition Required to Reform UN Treaty Bodies.” Open Global Rights blog, July 10, 2014, accessed May 21, 2017, http://goo.gl/efvLOe. strong support from the High Commissioner for Human Rights is required for the ongoing process of TB strengthening to be effective, and to notably deliver good results on implementation of recommendations.