a view from the Southern Cone and Andean Region

The human rights and citizenship movement has been a key agent in the processes of democratic consolidation that have taken place in the Andean Region and the Southern Cone over the last two decades. Yet civil society organizations need to change their strategies in new post-dictatorial contexts. In this article, some of the central challenges that confront these organizations will be identified. I would especially like to thank all my colleagues at the Ford Foundation Office for the Southern Cone and Andean Region for their valuable feedback on earlier versions of this article. The suggestions of Alex Wilde and Michael Shifter were also extremely useful.

The human rights movement has been a key agent in the processes of democratic consolidation that have taken place in the Andean Region and the Southern Cone over the last two decades. In the Southern Cone, the claim of human rights violation victims to obtain truth and justice made up one of the axes around which post-dictatorial transitions revolved; in the Andean Region, the role of civil society organizations that reported heinous crimes perpetuated or backed by agents of the State has also been a central component of the political agenda of the region. Beginning with those first steps, human rights organizations were expanding their original sphere of influence, actively taking part in issues as diverse and current as the struggles against poverty and corruption.

Such leadership has been accompanied by a transformation of organizations dedicated to the protection of rights—organizations which ceased to be basically dedicated to the reporting of sponsors of systematic and unacceptable violations so that they could shape a movement much more diverse in its composition and aims. In its early years, the human rights movement was fundamentally made up of organizations of victims and relatives—especially in the countries of the Southern Cone—and of organizations of attorneys that supported the demands of these groups—with greater development in the Andean Region.

Beginning with the restoration of democracy in the countries of the Southern Cone and with processes of larger rights awareness which are being developed in the majority of the countries of the continent, especially from the nineties onward, the world of civil society organizations, which are organized in demand to fundamental human rights, has been expanding in different directions.2

On the one hand, civil movements begin to organize themselves to take aim at not only the safeguarding of rights to life and physical integrity, but additionally aspire to the consolidation of a democratic system that ensures the participation of the larger majorities in the public agenda. At the same time, organizations that defend the rights of some group in particular, such as those that unite women; indigenous peoples; persons with disabilities; racial, religious, or ethnic minorities; as well as minorities of sexual orientation, amongst others, are achieving a new level of development. Many of these organizations form part of social movements that, in many cases, predate the formation of groups for the defense of human rights (such as those linked to indigenous peoples); however, what is new about these organizations in recent decades is that they have additionally assumed a perspective of rights in their principles and actions.

Similar to the diversification process that continues to change the landscape of civil society organizations, the recognition of human rights in new, post-dictatorial contexts, and in general, in all countries of the region, has been accompanied by a growing “officialization” in the field: the governments themselves, that were previously declared enemies of human rights, are beginning slowly but systematically to promote the defense of these principles.3

While in many cases this promotion is primarily rhetorical, it is without doubt that this new situation, in and of itself, is an advance and has led civil society organizations to alter their strategies in order to go beyond the mere defense of a value (which appears now to be socially shared). In this new scenario, human rights organizations needed to revise their traditional paradigm of work which was primarily designed to confront heinous crimes and unacceptable crimes sponsored by State agents acting to suppress the enemies of an authoritarian government. It should be emphasized, at any rate, that this crisis of the traditional paradigm, which has directed human rights work, is not a phenomenon limited to Latin America but instead assumes in this geography traits specific to the region while at the same time responding to a context at a global level. This situation, which has been classified as a “midlife crisis,”4 reflects the important challenges that the human rights movement must confront in order to preserve levels of impact and relevancy that it had in the past.

One of the most important consequences of this appropriation of the discourse of human rights on the part of democratic governments has been to open up the opportunity for working toward the inclusion of a rights perspective in the formulation, designing, and application of public policies. This endeavor, however, has not been exempt from difficulties. A context of complex, and in some cases, conflicting, issues confronts the organizations with a reality in which there are high levels of poverty and social exclusion, fragility with regard to the institution of democracy, and the growing leadership of different social agents which take to the streets in carrying out politics. In addition, questions of an internal nature linked to the history and current situation of civil society organizations also present significant challenges for the realization of goals and have propelled a process of reflection on goals, priorities, and responsibilities of human rights organizations launched in the Southern Cone and Andean Region, which give account for this new scenario.5

With that in mind, this article will identify some of the central challenges that must be confronted by human rights and citizenship organizations,6 like the question of the representativeness of these organizations, their relation to the State, the construction of alliances with other national and international agents, the development of a revised communications strategy and the need for designing impact indicators that allow for an assessment against achieved benchmarks. In order to tackle these issues, this article has been structured in two parts, in addition to this introduction: a first part dedicated to the work of human rights and citizenship organizations as it relates to public policies and a second part that analyzes the challenges that these organizations must confront for the carrying out of these endeavors.

Human rights and citizenship organizations have come to work in an increasingly systematic way with regard to the incorporation of the rights perspective in public policies, conscious that only these types of actions will allow for the maximizing of the outcome of their efforts in achieving a larger and more diverse world for society. In some cases this work can have a quantitative goal: to arrive at advances for a minority sector or in individual cases to reach a significant part of society (which some have called “the challenge of quantity”). In other cases, by contrast, they are attempting to secure access to benefits enjoyed by the majority for minority groups who have, historically speaking, been postponed access.

In search of these goals, civil society organizations have organized their work around four benchmarks:

i. To render a law or public policy invalid : the human rights movement has traditionally attempted to stop the State in its designing and application of policies, practices, or laws that directly result in the violation of fundamental rights. The basic tool for this type of action is litigation, alleging that these laws or practices are unconstitutional.

ii. To contribute to the designing of public policy : in other cases, civil society organizations are invited by the executive or legislative branch to participate in the designing of a policy that involves human rights issues. In the majority of these cases, the initiative to invite civil society organizations belongs to the government or congress, but in general, those organizations have previously communicated their proposals and sent the message that they have “something to say.” With many opportunities, a previous stage for this kind of work involves campaigns that hope to create consciousness about an issue in particular, with the object in mind that it is correctly nurtured by the appropriate public official. In these cases it could be said that the organizations are helping to create the political desire necessary for the formulation of a public policy but the designing itself of the policy is necessarily a collaborative endeavor (when those in authority decide to involve those who originally propelled the issue). It is necessary to point out, at any rate, that this is the assumption when the relationship between the State and civil society is friendlier, in the sense that they would seem to pursue the same goal. In point of fact, in this situation it is very rare that advances can be particularized through the path of litigation (which is a route of a confrontational nature). A partially distinct situation appears when organizations promote the approval of an international human rights treaty. In these cases, organizations contribute to the designing of an international norm that eventually must be implemented as an internal policy within the States.

iii. To promote the revision or correction of a law or practice : perhaps the greater part of the actions of civil society organizations around public policies can be included in this entry. It involves those cases in which a public policy does not violate human rights or citizenship per se(as can be the case with laws that grant impunity). In confronting problems of this nature, the actions of civil society tend to be greatly varied, for example going ahead with a communications campaign that compels the State to revise a law, or through the gathering of information demonstrate the consequences of a specific practice. The decisions of supranational agencies for the protection of human rights (such as the United Nations Human Rights Committee and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights of the Organization of American States) are also able to play a fundamental role in achieving these kinds of changes. In the case of litigation, it is interesting to see that they are not only observed in those instances in which a judicial decision compels the revision of a law or practice, but are taking the initiative to promote collaborative meetings between civil society and the State beginning with the premise of an “unconstitutional state of things.”

iv. To participate in the implementation of a policy : in some cases, agencies of the State invite civil society organizations to participate in the application of a specific public policy. In these situations it may be that the invitation is for the going ahead of tasks of a more operative nature like, for example, collaborating on a food distribution plan in order to ensure the arrival of the largest amount of necessities possible. It is difficult to consider these endeavors as similar to those that have been analyzed at previous points, in that the contribution of organizations is not necessarily at the level of ideas but is limited to the carrying out of definite activities by state agencies. However, in many other cases the invitation is not for the carrying out of actions of an operative nature but actions that will have a direct impact on the way in which policies are put into practice. For example, training activities for government officials who will be expected to comply with a specific law undoubtedly will directly impact the ultimate form that a public policy takes. When an institution is invited to carry out the follow-up to a specific State action it also contributes to ensuring the protection of fundamental rights. In many cases it is impossible to draw a clear dividing line between more operative activities and those that have a more substantive end, inasmuch as during the design and application of any policy civil society organizations will probably be called on to perform both types of work.

In order to achieve these benchmarks, civil society organizations have gone ahead with different actions and strategies for “impact,”7 such as lobbying, litigation and legal assistance, international advocacy, training and education, producing of information, and organizing of alliances and communications. This list is not exhaustive with regard to all the actions that human rights and citizenship organizations carry out but is limited to just those organizations whose ultimate objective is participation in the development and implementation of public policies. Other fundamental work that these organizations undertake, such as psychological assistance to victims of torture and sexual aggression, have not been included in this description owing to the fact that they do not aspire (at least in an immediate way) to change public policy but achieve reparation (although it is partial) for the damage caused.8 It is necessary to keep in mind that to have an impact on public policies it is not enough to undertake one of these activities but that more than one of them must be coordinated and, often, it will be necessary to carry out a strategy that includes all of them or at the least most of them (in the identifying of these examples that are offered in the descriptions below, the inclusion of a case of one action or another is many times arbitrary owing to the multifarious nature of actions that are called for; the same example could have been included in another category.)

At any rate, it has been opted in this article to organize the presentation of these activities and strategies into seven areas:

i. Lobbying : these actions for impact are those that involve these organizations in a direct dialogue with the authorities of the executive branch and congress. In the early years of human rights work this task was almost non-existent due to the openly hostile policies of the authoritarian governments against this sector; however now human rights and citizenship organizations direct an important amount of economic and human resources at informing those in authority of the positive and negative consequences that the eventual sanctioning of a law or decree would have, preparing, for example, documents for discussion or conducting interviews with those directly involved.

ii. Strategic litigation and legal counsel : the work of litigation and legal assistance was that which, in a certain way, gave rise to a human rights movement in the region in the decade of the seventies (together with the gathering of information, which is analyzed farther on). From their inception, many human rights organizations dedicated themselves to assisting victims of State terrorism and, when it was possible, sponsored them in the courts. If in the early years the formation of these organizations responded in part to a kind of immediate reaction of solidarity with the victims and a quest for justice in the face of the atrocities that were being committed, with the passage of time this work gave way to actions of assistance and strategic litigation. Thus, today it is possible to prove that legal assistance work is more focused on relieving a sponsor of violations or developing pilot experiences that, in one way or another, may provide an answer to the serious situation of lack of access to justice that can be observed in all the countries of the region. In many cases, assistance work is becoming a “cable to the Earth,” with regard to the daily reality of organizations that are performing at a more superstructural level, or in a way in which they manage to identify eye-witness cases that create an inquiry against the sponsors of serious human rights violations. In litigation work, from the onset, in which the largest amount of possible cases was sponsored, among other reasons for documenting grave and systematic human rights violations that were committed on a daily basis by agents of the State (or with their acquiescence), a more selective policy of sponsorship came to pass, in which the selection of a case for its presentation before the courts conformed to a series of requisites linked to its possible social impact.9

iii. International advocacy: the work of local or national organizations with international counterparts is also found at the origin of many institutions. The human rights movement in the Andean Region and the Southern Cone was established over the foundation of a fundamental alliance with international organizations such as Amnesty International or Human Rights Watch, looking to take maximum advantage of the international instances of human rights protection by international agencies belonging to the United Nations (UN) or the Organization of American States (OAS). In this context, the national organizations looked to the exterior for the attention and protection they were not receiving from their own countries.10 From that background, human rights and citizenship organizations have acquired experience and developed expertise in the area that is still one of their greatest assets, taking advantage of the concern of governments in presenting a favorable international image in a global scenario that is increasingly more interconnected.

iv. Training and education : numerous human rights and citizenship organizations carry out important work in human rights education, for example, pushing forward the incorporation of modules on discrimination into the official curriculum of public schools. However, this section will not tackle this type of work in education but that work which organizations carry out with the immediate aim of participating in the application of public policy. This is the case, for example, for training activities for judges and public prosecutors carried out by some organizations with the purpose of advancing in the proper setting the progress of specific legislation. The tasks of training and education look to ensure the proper application of a law and, in this way, participate in the execution of a specific public policy linked to questions of human rights. Other types of training and education activities associated with this objective are those directed at journalists, for example, for achieving better coverage in areas of justice, with the aim of securing a more informed public opinion and instigating a better debate of public policies.

v. Producing of information: from their inceptions, the production of information has been the principle tool for human rights organizations.11 Probably more so than for any other type of civil society organization, where in the case of human rights violations the phrase “information is power” is appropriate. Beginning with this certainty, human rights and citizenship organizations assign a significant proportion of resources to the production of reports and other types of documents that register fundamental rights abuses. The most notorious of these is the production of annual reports on the state of human rights. Additionally, annual reports on specific questions (that is to say, without claiming to tackle the entire spectrum) are prepared. In addition to these reports, civil society organizations are constantly generating information that is even not always designed for general diffusion (at least in the short term). It is beyond doubt that the task of gathering information has become increasingly sophisticated and therefore civil society organizations have often needed to draw upon the counsel of experts, a tendency that is still incipient and will probably make itself known with more force in the years to come.

vi. Organization of alliances : one of the strategies which have generated major benefits for work in human rights and citizenship is collaboration with other social agents. During their early years, scarce, existent organizations were working in a very united way and were searching for the support of other agents in the exterior or in their respective countries, according to the available possibilities. (The case of the Catholic Church is one example. In countries like Chile, it played a fundamental role in the reporting of human rights violations during the military dictatorship,12 while in Argentina it turned its back on the calls of victims, although its own members were involved.13 ) More recently, civil society organizations have searched for other forms of collaborative organization as well as new allies. One alternative is the construction of a formal network that would even adopt its form to a new organization. However, such jointures do not establish permanent institutions in all cases but, dependent on the opportunity, involve specific or temporary alliances for the achievement of changes in some area in particular.

vii. Communications: without doubt the most effective communication activity for impacting public policy are campaigns that are carried out by organizations or alliances of organizations for the moving forward of a proposed law or, more largely, for calling attention to the need to change a practice or regulate a right. Beyond these massive campaigns, civil society organizations in the last few years have looked to develop a larger capability for mapping out more sophisticated communication strategies beginning with the recognition of the multifarious nature of the audiences they need to reach. Some organizations are designing increasingly more diverse communication products, with the object of drawing the attention of some specific sector. Organizations have often incorporated professional journalists into their staff for taking over what is now the communications policy in general, or in particular, the organization’s relationship with mass media, which has been reflected in a larger media coverage of their activities.

Carrying out these activities and achieving the goal of influencing public policies brings coupled with it new challenges for organizations that aspire to make this qualitative leap in their work. In so far as activity in human rights and citizenship moves away from humanitarian defense to dedicate itself to strategic litigation and advancement of initiatives for a larger participation of the citizenry to a more democratic designing of public policies, civil society organizations must confront a series of new problems associated with this revised leadership.

The journey from work at a local level or assistance work, for example, to the formulation and design of a public policy means, among other things, a change of scale: organizations that involve themselves in these kinds of endeavors work to change living conditions of a significant fraction of the population. In this context, a question often appears: who do those organizations represent? And connected to that: what legitimacy do they have for carrying out this kind of work? While in many cases these inquiries are made with a “lack of faith,” by those who are interested in quieting organizations, they really involve questions that deserve an answer, especially because the organizations allege to work in favor of a greater (or better) democracy.14

In their beginnings, human rights organizations did not have to confront these types of questions. The fact that in many cases the organizations were made up of victims or those who represented them was enough to grant a legitimacy of “origin,” in the sense that they were representing a collective of which they formed a part. Nevertheless, the passing of time and above all an enlargement of the agenda have necessarily caused a crack in that historical legitimacy. Especially coming from sectors closer to the political parties, there is a tendency to allege that while representatives or senators are legitimate representatives of the interests of those who have voted for them, civil society organizations defend the sectorial interests of minorities, conflicting with those of the majority. In some countries especially, the fact that civil society organizations are financed principally with contributions from the international community adds to these questions the issue of the supposed defense of outside interests.

With respect to this, in the first place it is necessary to point out that while legitimacy and representativeness of the organizations is often a narrow link, the issue involves two kinds of questions which must be differentiated. In this sense, questions related to the lack of an electorate that tenders support seem to demand that the only legitimacy possible for public agents is a democratic legitimacy, that is, one supported by voting. In the face of these types of criticisms, organizations tend to insist on the special nature of the position that they defend—in favor of human rights and citizenship—and do not necessarily need to have the majorities of a society behind them, and that in general values are involved that must be especially protected from the majorities or their representatives, as they are exactly those who can put them at risk.

Associated with the above, another possible answer to challenges concerning legitimacy is related to the capability of the organizations and their demonstrated expertise in the issues in which they intervene. In this sense, it would involve a legitimacy rightly “acquired” by the worth of their interventions—similar to, for example, the means of communication open to prestigious persons whose opinion can be very influential, even when they do not “represent” any sector in particular. Organizations would act in this case as “experts” that defend universally recognized values (of human rights and citizenship).

While these lines of argument—for quality of work and the defense of universal values—adequately address the mentioned questions, it should not be inferred by the above that human rights organizations do not have to worry about their legitimacy. A question associated with their legitimacy and that has come to generate a growing preoccupation in recent years is the accountability of these institutions. For some years, civil society organizations have occupied a privileged position in the public arena, and as a consequence, the natural result has been the emergence of demands for better mechanisms of control and that they answer to certain specific sectors. This does not mean that those said mechanisms must be similar to those that oversee government bureaus or that the workers of these organizations have to be treated as public officials, but it becomes clear that the question of the responsibility of these organizations, or their accountability, has come to acquire an importance directly proportional to the growth of their influence, and becomes a central issue when the situation involves their participation in the gestation of public policy (a task that fundamentally lies in the hands of the representatives of the people.)15 The ways in which this accountability must be adopted are still found in discussion and it is hoped that the organizations themselves are the leaders for this design. On the one hand, it is necessary to advance the defining of control mechanisms on the part of the State so that they address the current relevancy of these organizations, at the same time not imposing arbitrary or unnecessary restrictions to their action. On the other hand, it also seems necessary to design standards with transparent rationales, so that whatever legitimately interested person can access relevant information about the organization. Those levels of transparency, however, must be adapted to the needs of the civil society organizations, for example, not putting at risk their representatives.16 Some organizations are taking the initiative to begin the development of objective and transparent criteria for their own accountability, and the advances that are achieved in this area in the short term will prove crucial for the off-setting of potential challenges.17

Another challenge to the legitimacy of these organizations is related to the enlargement of the agenda for work in human rights and citizenship and the inclusion of new groups of human rights violation victims and for defense organizations of some rights in particular. The growing leadership of those movements which promote rights in a particular sector or one type of right not only enlarge the horizon of human rights work to areas unexplored up to that moment, but, in turn, indirectly question traditional organizations. Some of the new actors in the area maintain that, while their claims are circumscribed by a group or theme in particular, this is not distinct from the work that original agencies for human rights adopted from their inception, a work that was focused on the sponsors of human rights violations and reached only a reduced group of the population—in comparison with other practices that affected, for example, an indigenous majority. The activist conception of women’s rights demonstrates a tendency to incorporate special charters (for women, indigenous peoples, minorities of sexual orientation, persons with disabilities, etc.) to declarations of rights; this necessity of making additions demonstrates that the “universal” declaration was in reality a rights declaration for white heterosexual males without disabilities.18

In light of this situation, the legitimacy of civil society organizations that work in the defense of human rights and the promotion of citizenship depend, in a large way, on the capability they have to band together with other agents and in that way ensure a true universality for human rights work that incorporates all sectors. The legitimacy of the work in these issues is directly linked to their representativeness: those who aspire to participate in the designing of public policies that effect specific groups must not do it without a direct association with those directly interested. This means, especially for original organizations at the present moment, learning to act not as representatives of their own interests but as part of an alliance that requires the endorsement of those directly affected in its daily application. It is for this reason that these organizations must develop proactive strategies to ensure the necessary mechanisms that will safeguard the narrow link between their work and the interests of those that they aspire to represent.19

Human rights work began in this region with the intention of putting a stop to the heinous crimes that, during the decades of the seventies and eighties, were being sponsored by the States (dictatorships in the Southern Cone and weak democracies in the Andean Region). In this scenario, especially in the countries of the Southern Cone, the concept of the State that was employed during these first years was, without doubt, that of an enemy-State.20

The re-establishment of democracy in the Southern Cone re-opened an opportunity for rethinking this relationship; however, the process was not simple nor was it devoid of tension. On the one hand, the confrontation between the new governments and human rights organizations, which resulted in an almost immediate way from policies of truth and justice, was an insurmountable obstacle for settlement on positions. The official policies of reparation in general did not satisfy the demands of the victims and the organizations that represented them, leading to the delay of a shift in mutual perception that lasted longer than was expected. Many of the more traditional human rights organizations continued working with a concept of the enemy-State even in the context of democratically-elected administrations.21

At the same time, the very nature of political action supposed work in constructing agreements and mutual commitments that was often resisted by civil society organizations, resulting in distrust toward the public sector which in some cases persists up to the present. The Chilean transition to democracy proves very interesting as well when seen from this perspective, inasmuch as the human rights movement became divided between those who, coming from human rights organizations, started to form part of the blocks of the government administration and politically negotiated the nature of the democratic transformations and those who opted to continue in civil society organizations and self-relegate themselves from these conversations.

At any rate, the greater acceptance of human rights throughout the region has permitted civil society organizations to search for their own place in a continuum that moves away from the conception of an enemy-State to that of an ally-State or even friend-State. This enlargement of territory led to the creation of different organizations, more or less radical, that would find their own place in the tension. On the one hand, it is possible to identify organizations that even today perceive the State as a kind of leviathan, which it is necessary to confront with all available force. While it becomes difficult on occasion to harmonize this point of departure with the need to deepen the democracy, these organizations assume that their contribution is reporting on a government institution which is by nature abusive. On the other extreme, there are organizations that, operating from the recognition of the State as a friend, wind up losing their independence and become enveloped in a confusion of roles.

On the other hand, the reconfiguration of the States of the region, especially from the decade of the nineties onward (although in some cases, like Chile, it begins earlier, during the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet) also resulted in a responsive modification to the scenario. With the processes of privatization, the reduction of the influence and presence of the State in numerous sectors and with globalization, the bureaucratic apparatus has lost some of its territory as an exclusive agent and, instead, begins to be perceived often as a regulating entity which now must not only worry about the legality of its own actions, but also as a monitor of increasingly powerful third parties. This is the case, for example, with the role of the State in monitoring private security agencies or in protecting the rights of the less-favored with regard to the supply of essential public services (like potable water). Other actors such as transnational businesses and international financial institutions are acquiring growing importance and the accusatory finger of human rights organizations now has more than one target. At the same time, other sectors begin to make systematic challenges toward the State, inasmuch as it is asserted that the State does not necessarily respond to the interests of society in general but is controlled by a specific group that does not represent those excluded. Movements vindicated by indigenous ancestral traditions, from Zapatismo in Mexico to mobilizations in Ecuador and Bolivia, bring into question the State-Nation such as it has been known in Latin America. The case of the piqueteros (or “picketers”) in Argentina, especially in their more radical sectors at the worst moment in the crisis of 2002, have also been transitioning toward this type of establishment beginning with a practice that aspires to make them independent from official policies and construct their own community—which includes its own schools, hospitals, policies of revenue distribution, etc. In the rural sphere, perhaps the most notorious case is the Landless Workers’ Movement (MST) in Brazil.

It is in this changing scenario that the necessity to contribute to the development of the State as a protector of human rights has begun to develop with more force among civil society organizations. In the last few years, the crises which numerous governments of the region experienced, and which included the anticipated departure of democratically-elected presidents in many of those countries, have wound up painting a new landscape in which human rights and citizenship organization have been obliged to commit themselves more forcefully to the strengthening of democracy. In this sense, there are already few of those that deny the necessity of collaboratively working with the State, at the same time that many of those governments, given their weaknesses, produce among others, reasons for a crisis of representativeness, and have begun to invite these organizations into the process of formulating and putting into motion public policies in a way that is significantly more systematic if compared to the past.

However, there is no necessary, clear understanding with respect to the way in which the State and civil society must collaborate with each other on this issue. As partially results from the absence of an ideal State at the heart of organizations, as well as an inefficiency of administrations and inexperience on both sides, the intentions of working together have not always been fruitful. These difficulties have become more manifest recently, with the rise in functions of several governments regarding the human rights movement that have adopted for their lines important benchmarks for this movement and have established more systematic work relationships with civil society organizations.

A principal challenge for the collaboration between governments and civil society around the construction of a State protector of human rights is the inefficacy of many of the administrations of the region. One of the serious shortcomings of the democracies of the Andean Region and the Southern Cone is their incapacity to provide their inhabitants with essential goods and services. For this reason, the promotion of a State protector of human rights clashes with a reality of administrations incapable of achieving expectations. There are repeated cases of administrations with an unquestionable commitment to human rights (at least in some issues) that, regardless, have been incapable of deterring unacceptable practices. The case of torture in police commissaries is probably one of the most notorious examples of these failures, seeing as many governments, especially at a national level (and federal, according to the cases to which they correspond) have made efforts to eradicate this practice, but the political will is insufficient for disarming bureaucracies entered in supporting these types of isolated onslaughts.22 In the same sense, administrations (or governmental agencies) that have proposed confronting the corruption were in the majority of cases overcome by those same bureaucracies or even by the structures of their own political parties.

The role of activists and intellectuals of civil society in a public function is a question rarely studied in Latin America. This lack of attention is contrasted with the fact that these experiences result in a great usefulness for reflecting on the relationship between civil society and the State and the democratization of the process of defining public polices. Such experiences bring into question one of the principal reasons that generally is wielded as an obstruction to the participation of civil society organizations in the formulation and putting in practice of public policies: those that have developed a diligent manner of reporting and follow-up are recognized but are criticized by those who believe that they lack the necessary credentials for actively participating in the process of designing the policies.

There are many civil society leaders that have accumulated valuable experience in the formulation and execution of public policies that is as much linked with their interaction with the State as with their previous work in non-governmental organizations.23 Taking advantage of this expertise will probably be of great help for developing the know-how necessary for strengthening the relationship between the State and civil society.

If the different activities and described strategies above are analyzed it can be concluded that human rights organizations today do more or less the same as they did at their beginnings: influencing the government, litigating, gathering information and diffusing it, and mobilizing the international community for a “rebound effect” in the internal setting. The difference in their work does not seem to rest so much on the nature of the actions that they undertake but in the way in which they are carried out.

One of the differences in the way in which these activities are undertaken is the possibility of building alliances with other social agents or actors. Work in human rights began as an isolated action to confront authoritarian governments, so that its discourse was destined to be inevitably marginalized. With the passage of time, the changes in the political context, and the growing legitimacy which human rights organizations have achieved has stimulated a situation of varying correspondence.

However, the strong isolation of their origins has had consequences up to the present: the human rights movement was built around a nucleus of original organizations proud of their work that constitute a selective group which proves hard to enter.24

That sealed-off nature of the organizations also functions in the direction of an interior movement, with often loses sight of other agents and is concentrated too much on its own vicissitudes,25 in the worst examples, in a kind of “autism.” Such an attitude has implicated in the loss of valuable opportunities, by human rights organizations, for advancing toward their objectives on a base of alliances with larger sectors.

Organizations that promote citizen participation, and which did not suffer the same isolation that more traditional human rights organizations did, worked from their inceptions with a more diverse network of agents. However, apart from some exceptions, it can be demonstrated that even in these cases collaboration with other protagonists is limited. In these cases, it is observed that the organizations have a greater capability for coordinating amongst each other and working together; but these relationships continue being in some way a kind of interbreeding in the sense that they are limited to other civil society organizations with similar characteristics.

Neverthless, the work in formulating and putting into action of public policies requires collaboration with other, different agents from these organizations. In this sense, the lack of an exertion in democratic negotiation on the part of civil society leaders is notorious, and has, in many cases, been an insurmountable obstacle for these organizations. The best experiences of participation in public policies are observed in the context of alliances between different civil society organizations and other fundamental agents. Working with other organizations and being able to arrive at agreements with them is the first step in achieving an impact on a larger scale. However, the possibility of politically influencing and being persistent pursuant to those ends will depend not just on this “internal” coordination amongst civil society organizations but must include a larger group of counterparts.

In this sense, if human rights and citizenship organizations aspire to participate more actively in the formulation and execution of public policies, it becomes necessary to develop strategic alliances with at the least three sectors (there are many other agents with whom these organizations should formalize more stable alliances, like, for example, the business sector; however, it has been preferred in these pages to highlight three possible allies which have become fundamental for participation in public policies):

i. Social movements and grassroots organizations : especially in the way that civil society organizations at the current moment do not represent their own interests but a public interest and in many cases their actions are directly linked to the situation of specific sectors, it becomes fundamental to ensure channels of communication and situations of permanent representation with those other agents. Among social movements and grassroots organizations it is common to hear criticisms of “non-governmental organizations” that are often described as being merely intermediate or non-representative. Such criticisms are accentuated when they are augmented by related ethnic and racial questions. As much between indigenous peoples as between Afro-Latinos it is common to assert that they will only be able to build medium to long-term alliances with human rights organizations when these include representatives of their peoples in their staff hierarchy and in structured guidelines.

ii. Universities and centers for study : considering that the participation in the development of political policies requires a given level of expertise that in general is lacking among civil society organizations, the formulation of alliances with this sector has a strategic character. However, it is possible to demonstrate that these types of relationships are still significantly precarious. In effect, in many cases it is the universities themselves that are involved in the area of public policies, without the need for a stable link with civil society organizations; in other cases, centers for study have become marginalized in the discussion of public policies. None of these situations is ideal, inasmuch as, in the first case, the direct collaboration of universities in the designing of public policies can transform the debate to a technocratic dialogue or one for only experts, and even conspires against the participation of civil society organizations; in the second case, it is a waste of expertise that is invaluable for the ensuring of the eventual achievement of the sought goals.

iii. Political parties : the relationship between human rights and citizenship organizations and political parties is one of “love-hate.” Sometimes the political parties are erroneously assimilated into the apparatus of the State, and thus the tension between these two sectors has relatively the same characteristics as in the description of the previous apparatus. In other cases, the concerns of civil society organizations with respect to political parties are reduced to two preoccupations: the risk of being co-opted and the dream of their own party. On the one hand, organizations tend to be alert in the face of whatever possible interest political parties might have by incorporating them into their lines and in this way rendering them harmless. While it would be naive to dismiss this motivation in many approaches, it calls attention to the fact that this involves a risk of immobilization. On the other hand, in the face of the crisis of representativeness of those parties, some organizations have proposed the possibility of creating their own space of political participation through the creation of an alternative electorate. Experiences such as that of the Workers’ Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores), which has infiltrated the government in Brazil, nourish these hopes. While the possibility of forming a political party that invites some sector of organized civil society always appears as an attractive option, it becomes worrisome that these organizations might not be able to exit this dual role which limits their possible alliances with a fundamental agent for the construction of a solid democracy.

One of the key alliances that human rights organizations built from the very moment of their creation was with international organizations and supranational agencies for the protection of human rights. This society continues to be fundamental for local organizations. However, after more than three decades of ties, it seemed that a reinvention of this cooperation might be necessary, and is a product of changes that have been observed at national and international levels, as much as a result of what is referred to as the acceptance of the discourse of human rights, as the diversification and larger development of key agents in the field.

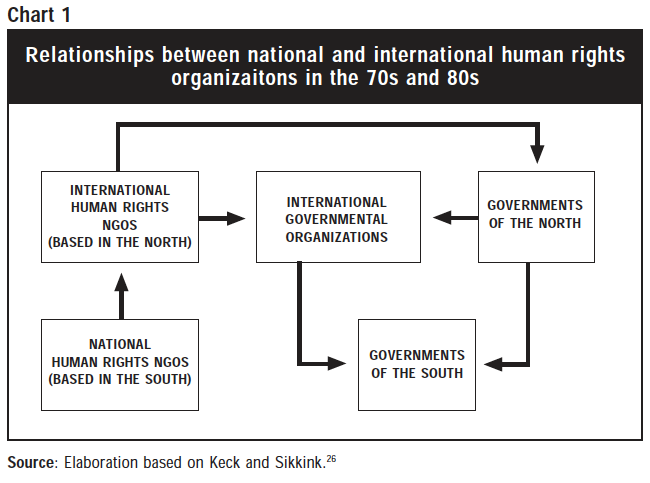

For a better understanding of these changes perhaps it is helpful to examine the relationships between international and national organizations in Charts 1 and 2, which respectively describe these connections in the past and then the present.

This chart shows what is probably a very accurate description of the way in which international and national human rights organizations were inter-related during the seventies and eighties: human rights organizations that worked at a national level collected information that non-governmental international organizations used to make an impact on governmental international organizations (such as the United Nations or the Organization of American States) and in view of the governments of other countries that defended the cause of human rights, who, by their turn, would take the opportunity to pressure the government in question.

This system is still utilized in many cases and especially with relation to some (few) governments of the region that still today ignore the demands of human rights at a local level, though they listen more attentively to challenges from the international community. In this sense, such interaction is not only still practiced but sometimes continues to be very effective.

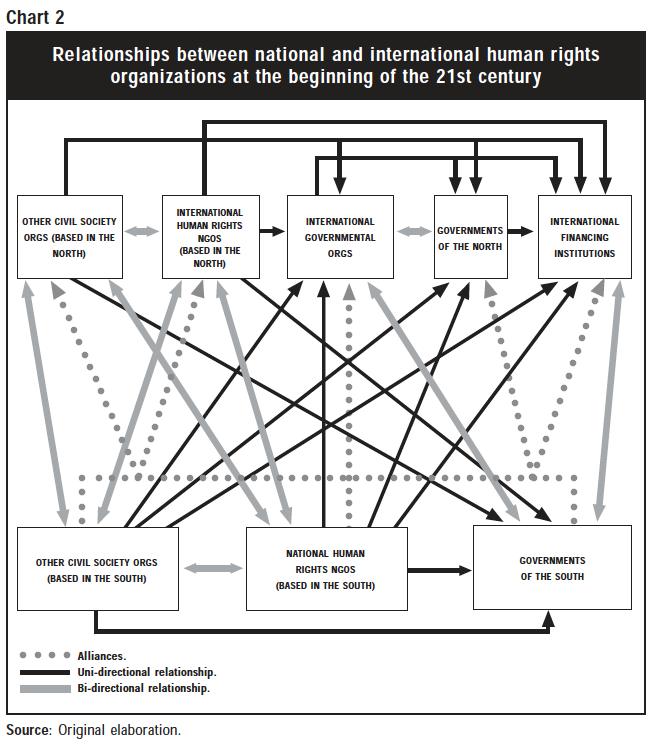

However, by looking at the following chart, which tries to reflect the current nature of the relationships among national and international human rights organizations, it is possible to appreciate that this type of interaction is very far from being the only form of collaborative work between the two.

As can be seen in Chart 2, the relationships between national and international human rights agencies are much more intricate at the present moment. Various forms of interaction are recognized, represented by the lines of the chart. On the one hand, the simple, solid lines with one arrow describe classic unidirectional relationships in which one actor attempts to influence the other. The solid lines, with two arrows, on the other hand, describe channels of two-way or bi-directional communication, in which the two parties give and receive. Finally, the dotted or segmented lines map out a new form of alliances, which have arisen in the last few years and which will be examined farther on.

Different from Chart 1, the relationship between international and national organizations is at the present moment bi-directional. This means that even when in some cases the organizations that work at a national level continue to provide information to international organizations, there are also other types of exchanges in which, for example, national organizations provide their expertise to each other, try to design impact strategies together and even aspire to influence the agendas of international organizations. The relationship between national and international organizations is itself nearing an exchange which is much more one of “equals”—even when some international organizations are still unaware of the situation. While it is true that there are still enormous differences between the national and international organizations (among them, a significant difference in levels of financing), at least between organizations which carry out similar tasks there is a much more equitable relationship. One of the reasons for this leveling out is that national organizations often now do not require international organizations to be heard by their own governments. As it has been examined, human rights organizations that work at a local level have achieved during the last ten years a level of exposure and unchecked influence which creates a situation in which their governments are unable (or do not want) to continue ignoring their demands.

At the same time, non-governmental organizations that operate at a global level might sometimes not need national organizations or international governmental organizations to exercise influence in specific countries. To cite an example, the leadership that Human Rights Watch or Amnesty International has achieved in Colombia as agents in the internal process is qualitatively distinct from the traditional role of original international organizations as “processors” of information gathered by third parties.

In this more complex scenario, it is common to encounter some paradoxes. For example, in the case of the campaign for the ratification of the International Criminal Court, it was very difficult during the first few years to actively involve organizations that worked at a local level, in spite of the principal benefits of a court of this kind which was undoubtedly going to directly impact national situations. In that first stage, international organizations were the ones who worked arduously for the creation of this Court, while the national organizations had other priorities, associated with their urgencies and pressing contexts. That which makes this case particularly interesting as well is that on the part of the governments there was seen an unusual situation. Even though some governments of the South had in times past been tenaciously opposed to an initiative of this kind, they became here key allies of non-governmental international organizations, which instead were seen confronted by a traditional ally like the United States.

Another relevant characteristic of the new schema of relationships between national and international organizations is the appearance of other agents. While all these are seen included in the context of the second chart under a single category of “Other civil society organizations”–because of their difference from traditional human rights organizations—they represent a great diversity in new agents. This involves, in the case of development organizations that work at a local or international level on the anti-globalization movement, to mention just a couple of examples. Amongst international governmental organizations, the growing leadership of international financing institutions has also come to responsively change the issue of human rights. In this new context there are many more opportunities for the coordination of alliances and the identification of membership strategies for specific questions. In fact, toward the middle of the nineties, when many national organizations wanted more actively to promote the defense of economic and social rights, in light of the scarce receptivity that they encountered from international human rights organizations, they opted for partnering themselves with other types of international agents.

Among these new possible alliances true forms of South-South collaboration are outlined in Chart 2 (with dotted lines), in which organizations that work at a national level collaborate with their own government for the advancement of initiatives that are often resisted by governments historically friendly to human rights (and even resisted by some non-governmental international organizations). This is the situation that has been observed, for example, in the negotiations surrounding the World Trade Organization (WTO)–in which human rights organizations and governments of the South have promoted a common agenda on issues such as commercial barriers and intellectual property rights.

In light of this new situation, it is possible to infer some preliminary conclusions:

• The agendas of national and international organizations are increasingly different. This does not mean at any rate that the agenda of one is better than the other, but it is reasonable to predict more tension in the relationship between the two. The construction of an international agenda that represents all the actors involved will probably be an increasingly complex process if it hopes to enlarge the participation level of traditionally secondary actors. However, this will depend not only on the attitude that is taken on by international organizations in favor of the participation of other agents but also, such as occurred in the mentioned case of the debate process for the approval of an International Criminal Court, it will also depend on the capability of organizations that act at a national level to develop a work agenda at an international level—even in the context of complicated scenarios at a national level. The capability of organizations to act at a national level to collaborate with similar organizations in other countries will determine the increase in their capability of influence at an international level.

• A progressively larger leadership of local organizations will mean a relative loss of relevancy at a national level for traditional international actors, which in many cases will have to attend to the initiatives of their national counterparts and, for others, filling some vacancies that the local actors have not taken care of.27 At the same time, non-governmental organizations that act at a global level will probably continue their creeping change of focus away from work on the situation in other countries in order to concentrate on strictly international issues (such as the strengthening of international governmental institutions) and on foreign policy with regard to the issue of human rights in developed countries. At a national level, it can be expected that international non-governmental organizations will go on performing a key role in those cases in which there are still no strong organizations in the local terrain (a situation which is presented in a few of the countries in Latin America) and in situations where conditions for those organizations to carry out their activities are absent. A partially distinct case is that of international organizations that have specialized in an area of work in particular, as for example, the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ). The role at a local level of these kinds of expert organizations will continue to be of special fundamental relevancy in what is referred to as the national construction of capabilities in their areas of expertise.

Communicating the message in favor of respect and vigilance toward human rights has been one of the central goals of this movement. In as far as making visible a human rights violation is the first step in remedying it, civil society organizations have concentrated the greater part of their effort in this direction. In point of fact, the formula “naming and shaming”29 was and continues to be one of the most powerful tools in human rights work.

However, in the way that the actions in defense of human rights become more complex, the mere identification of those responsibilities is insufficient for the attaining of new goals as in many current structured violations of human rights the way of rectifying the situation is not simple. If when Amnesty International was created it was obvious that the problem of prisoners of conscience ended with the liberation of whoever was detained, the necessary means for remedying the lack of access to healthcare or, even, police brutality, is significantly more complex, in the sense that those responsible are more diffuse, injustices usually have an endemic origin and the solution implies numerous variables.

In this context, although the task of organizations monitoring human rights situations and exposing the more serious violations, for example, in annual reports, is still a basic activity, there is a marked consensus concerning it—that it does not provide for achieving the objective of rectifying the situation. In spite of that acknowledgement, the attention that the human rights movement has discharged to this problem is still disparate. While some of these institutions undertake excellent work in this area and have managed to position themselves very well in mass communication media or have developed their own very successful tools for diffusion, many others today have great difficulties in making their message reach its audience just as in the significantly adverse contexts under dictatorships or authoritarian governments.

These difficulties, at any rate, increase when it is an issue of influence on public policies. In order to achieve this goal it is not sufficient to develop a systematic means of dissemination, but it becomes necessary to count on strategic communications that “clear the path” of obstacles and enable movement toward the formulation of policies respective of human rights. A strategy of this kind should move away from an evaluation of the context in which it wants to exercise influence, including an analysis that identifies possible allies, adversaries to neutralize, and conceivable scenarios. Simply working off of an analysis of this nature will make it possible to identify the audience which needs to be sensitized and develop the appropriate message for reaching each one of them. The last step, in this schema, will be to specify the activities essential for diffusion, through the most appropriate channels.

However, it can be demonstrated that civil society organizations are in general far from a work scheme similar to the one proposed. The strategy in this area for many civil society organizations depends in a large way on individual desires and the personal intuition of some of their members. While in many cases the “nose” of those who are in charge of these issues proves skillful, it would be helpful to develop more solid institutional capabilities if there is a desire to participate in a more active way in the debate on public policy.

Many civil society organizations even have difficulty in determining key audiences: determiners of policy, public opinion, other civil society organizations that are working on the issue and other social groups directly involved (including, depending on the issue at hand, unions, grassroots organizations, business sectors, ethnic and racial groups, other minorities, etc.); and, among all of these, differentiating potential allies from adversaries. In general, civil society organizations have enormous difficulties in developing appropriately communicative materials for each one of these publics. While these problems are understandable in light of a lack of human and economic resources, they continue to be a large disadvantage for organizations that prepare their pieces for diffusion, producing too many sectors at which to direct themselves or prioritizing one over another.

Another challenge for the participation of human rights organizations in the designing of public policies is preparing the appropriate message. In as far as it is not sufficient to simply identify the situations with violations of human rights, these organizations must develop the necessary institutional capacities to present a discourse which, together with reporting, includes the proposal of the actions that would be able to modify the situation. The participation of organizations in tasks of this kind requires a larger or better capability to communicate, as well as routes for solving the problems that are reported.

Finally, it is also important that the organizations, at the moment of planning the actions of dissemination, develop strategies for working with the different media of communication, without ignoring the advantages and disadvantages that each one represents. It can be demonstrated that many organizations prioritize in almost an exclusive way the work with mass communication media.30 While it is beyond doubt that the access to the major media becomes a fundamental tool for the discussion of political policies and that, in addition, transplanting and maintaining the debate in this arena guarantees a reasonable level of transparency, this strategy can also entail important costs. On the one hand, in this model the message of the organizations arrives to those who design public policies through an intermediate; on the other, the rules of the political debate in the public opinion are distinct from those that rule the discussion of determiners of policy and, in this context, the discourse on media has in general a bipolarity that does not facilitate the construction of agreements.

Considering then the limitations of mass media, for participating in the designing of public policy, civil society organizations should explore, for example, the development of tools of communication aimed especially at the public sector, thereby accessing it by alternative routes and lowering the degree of interference with the message. In the same sense, the focusing of the field on mass media communication commercials is necessarily sufficient either for reaching audiences identified above as fundamental for the discussion of public policies.

“There are few tasks more important, and few more difficult, than adequately measuring advances in the field of human rights and evaluating the impact of human rights organizations.”31 The humanitarian character of human rights work in many cases means that results can be measured by the number of lives saved. However, these types of indicators prove insufficient for evaluating the general situation of human rights in the context of the current democracies in Latin America.

This difficulty in measuring the current application of fundamental rights has been acquiring growing relevance in the last few years. On the one hand, there are an increasing number of cases in which a diagnostic on the human rights situation in a specific country described by a civil society organization was challenged by governmental authorities. In contrast to what was occurring during the authoritarian government regime who questioned the “ideology” of human rights defenders (who they directly accused of inventing their records), today the governments question the methodology utilized by the organizations and say that the numbers are not representative of the reality. The Colombian case, where there is a virtual “war of statistics” between state authorities and non-governmental organizations is the clearest example of this tendency.

But, in addition, the necessity of designing appropriate mechanisms for measuring advances in the human rights situation is also fundamental for evaluating the impact of civil society organizations. In the section referring to the legitimacy of human rights and citizenship organizations, it is pointed out that one of the possible answers for these growing challenges is linked to the quality of the work carried out. In this sense, the backing of tools for the measurement of outcomes is without doubt a great help in reaffirming the importance of the work developed by these organizations.32

Among civil society organizations references to the need for an evaluation of impact gives rise to many doubts. In the midst of a very demanding daily work dynamic, numerous organizations resist undertaking the task of taking an “inventory of results.” International cooperation has been in this issue part of the problem, in that there is a track record of frustrated initiatives on the part of cooperative agencies, those which promoted the use of a series of indicators (in their majority quantitative) that were difficult to adapt to the needs of civil society.

One of the reasons human rights and citizenship organizations have brandished for explaining the difficulties that must be confronted for the employing of these measurements is that an often changing context impedes the forward movement of profound processes of planning that, by the time which they have been completed have already become noncurrent. This constitutes, without a doubt, a large challenge for civil society organizations, especially in the context of political instability that persists in the region. A very tedious planning process, for example, could conspire to take advantage of unexpected opportunities, which are frequently the only method which participating organizations have in the process of defining policies. The changing context and the lack of a rational discussion between the actors involved that can make their decisions based on sectorial pressure or faced with the necessity of giving quick answers, renders the designing of political policies a process sometimes random and sometimes with an aspect of heteronomy.33 In this context, it is argued, the identification of benchmarks and indicators can become more of a disadvantage than a tool.

In a manner partially conflictive with the above, another of the repeatedly seen obstacles for an appropriate measuring of impact is that the outcome of human rights work can only be observed in the long term and that to aspire to indicators of success over a couple of years can be counterproductive because it requires the search for immediate achievements that by their nature are more difficult to sustain over time. In this line of argument, the work of human rights and citizenship aspires in the last instance to a cultural change that, as such, requires several generations for its achievement. The advances in the short term must only be understood as small steps on a longer road and thus their immediate impact should be in relative terms.

This relationship between the short term and the long term is fundamental for the evaluation of the work in public policies. In effect, being alert to taking advantage of opportunities that this context offers is indispensable if one wants to advance in the protection of rights and verify that these achievements are preserved over time it is something that can only be evaluated in the long term. This interaction and partial conflict between both levels of work requires a complex approach that often surpasses the experiences of the involved organizations. Especially in the context of instability that predominates in the political scene of several countries of the region, the unpredictability of the process of designing political policies makes it so that those decisions are fragile and that policies can be revised—and even reversed—with relative ease. It is because of this nature that it becomes necessary to differentiate with more clarity the work in this context surrounding the structural causes of human rights violations. Only in as far as sporadic opportunities are taken advantage of for the advancing of goals in the long term can results be obtained that endure over time.

Perhaps the process that best exemplifies work regarded in a coordinated context with the quest for long-term goals is the work of original human rights organizations in the search for truth and justice for human rights violations committed during the military dictatorships. In this case, human rights organizations took advantage of each opportunity that the situation gave them, even in the adverse context of military regimes, not only for the saving of the lives of persons at risk, but also for avoiding what would have consolidated impunity for these serious crimes. Throughout thirty years of struggle, at the same time that immediate results were pursued (often in response to urgent problems), strategies were designed that were not necessarily going to give rise to advances in the short term, such as lawsuits initiated during the dictatorships and that had to be resolved by judges in the majority of cases associated with de facto regimes (and which in many recent cases are beginning to bear fruit.)34

Another additional challenge for the evaluation of work in human rights and citizenship is the lack of reliable indicators that not only make the measurement of the results difficult but can also be an additional obstacle for evaluating the human rights situation. On enlarging the work in areas such as social rights, organizations require other instruments of measurement in that the description of the situation on the foundation of eyewitness accounts is not always the best formula. The development of human rights indicators not only would help to measure the impact of the organizations but would also serve as a powerful tool for applying pressure to governments and others possibly responsible for action or omission.

In a world in which there is more and more data for the measuring of political and social situations, with novel indicators that measure the distribution of revenue (as with the Gini index) or the quality of the democracy,35 to cite a couple of examples, human rights work still appears too much devoted to monitoring on the basis of cases and sponsors that clearly become insufficient for evaluating the much more complex nature of rights violations that are seeking reversion.

At any rate, the difficulties associated with this challenge must not be underestimated. The fact of it is that the carrying out of these tasks requires a qualification and special training based on relevant data. Few issues have confronted the “old” and “new” generations of human rights defenders like the subject of measuring impact. Many of the activists that initiated the work believe that the development of indicators is a techno-bureaucratic question that does not justify attention. This posture is explained by the fact that, in its beginnings human rights work had very clear, immediate objectives whose achievement was easily verifiable. In a context in which the issue was saving lives and stopping atrocities that were committed on a daily basis, the results were “in sight.” More recently, in as far as the human rights field is becoming more complex with the incorporation of new themes and sponsors of human rights violations, that does not only have to be a state desire, a new generation of professionals has incorporated new work tools such as strategy planning and the development of strengthening schemata, opportunities, weaknesses and threats, that are often strongly resisted by their predecessors.

These differences, which are explained by the training that they have received and the experience of work in the field, is often translated as a confrontation between the more “political” sector, integrated by those who created the organizations and other leaders that, being younger, also have had a personal trajectory of this kind, and others, more technical, who conform to the idea of “professionals of non-governmental organizations.” On the one hand, then, it would be those who do not lose sight of foundational objectives and know how to achieve them without the necessity for “framed logic” (and which, in fact, often have been highly effective); on the other hand, professionals that manage a sophisticated variety of tools that, however, often move away from the political arena.

The scenario seems to indicate the presence of a crossroads at which it is necessary to decide between one of the two options that confront each other instead of going together: activists and strategists versus professionals and managers. Building alternatives among these two possibilities becomes fundamental for the human rights movement in the region, if one wants to maintain levels of historical impact. In the context of an enlargement of the field of work, that makes it much more complex. Only the development of leadership with necessary technical capacities but also backed by the quality of developing effective strategies ensures the necessary capabilities for directing these organizations at a level of systematic change and the obtaining of results on a larger scale.

In order to analyze the role of organizations in the designing of public policies, the measurement of impact can be approached on two levels: on the one hand, evaluating if the participation of these organizations achieved or did not achieve the modification of a specific public policy (in whatever of the four ways described earlier: rendering invalid a law or public policy; contributing to the designing of a policy; promoting the revision of a law or practice; and participating in putting it into effect); and, on the other hand, demonstrating the effects that these transformations had on the level of the protection of human rights. It should be emphasized that at any rate the change in a policy can mean an advance in of and itself for the protection of rights. This would be the situation, for example, with a law that recognizes mechanisms for the exertion of the right to the accessing of information. Beyond the eventual problems that can exist in the application of a normal dictum, their mere sanction constitutes an advance.

At the first level—if the participation of these organizations achieved or did not achieve a specific public policy—the manual Advocacy Funding,36 identifies three classic ways of measuring the success of initiatives of this nature. The first of the more basic is the evaluation of the process, which should determine if the campaign of impact resulted in the activities and products planned. A second way is the evaluation of the outcome which aspires to evaluate the effect which the campaign produced on the identified targets. The third alternative is more ambitious and refers to the measurement of the impact, that is, determining what effects those activities produced in the process of formulating the policies.

The distinction between advances in the process and the measurement of the outcomes, however, has generated certain confusions. Among civil society organizations it is common to hear that it is convenient to concentrate efforts on the evaluation of the process, in that this would permit a qualitative analysis (which might include, for example, a growing level of collaboration among the organizations), while the measurement of the outcomes would be more limited by including a quantitative perspective. For their part, there are those who point out that the evaluation of the process indicates how rights are to be protected, while the measurement of the outcomes reflects the levels of the effective protection of those rights (Hines, 2005)37 – a criterion that, applied to work in public policies, would mean the measurement of the impact of the organizations in the changing of a public policy would be the evaluation of the process, while the effects of that policy on the population affected would be the evaluation of the outcome.

The need to strengthen the capabilities for impact measurement in human rights and citizenship, however, does not mean the involvement of reproducing or replicating forms of evaluation imported from other areas. The identification of the measured outcomes, of the realized contribution38 or of the type of indicators utilized, must necessarily respond to the special characteristics of the work. To illustrate, some of the questions that organizations should ask could include: should we measure the outcome of specific cases or of the situation in general? Is it possible that improvement in one area of work signifies a worsening in another? Is a lesser advance in a priority area more important than a major advance in an area of secondary concern?