Changes and Challenges Following the First Ruling Against Brazil in the Inter-American Court of Human Rights

The purpose of this article is to present a general overview of the implementation of the measures expressed in the 2006 judgment against Brazil in the Damião Ximenes Lopes case, the first Brazilian case heard by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, and to discuss international responsibility for human rights violations. Drawing on official documents, articles and opinion pieces, this article reviews the background of the case, traces the steps taken by Brazil to comply with the judgment, and examines the consequences for the country’s public mental health policy.

The subject of responsibility in international human rights law dates back to the movement for the internationalization of human rights, which emerged in the Post-War period in response to the atrocities committed during the Second World War.

Following the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, what is now known as international human rights law began to be drafted through the adoption of important human rights protection treaties of both global scope (United Nations – UN) and regional scope (European, Inter-American and African systems). The global and regional systems, inspired by the values and principles of the Universal Declaration, comprise a range of instruments for protecting human rights on the international level. It is worth noting that these systems complement each other, supplementing national protection systems in order to assure the greatest possible effectiveness in the protection and promotion of human rights.

Brazil only ratified the main human rights protection treaties once the country’s democratization process had begun, in 1985. And it was with the Constitution of 1988 – which enshrines the principles of human rights and human dignity – that Brazil began to take its place on the international stage of human rights protection.

In this context, it should be pointed out that the growing internationalization of human rights evoked the designs of a universal citizenry, from which internationally assured rights and guarantees emanate. And, in this sense, it is important to emphasize that the study of international human rights protection is closely connected to the study of the international responsibility of the State.

It should be noted that international responsibility for human rights violations is important for reasserting the legality of the set of rules intended to protect individuals and assert human dignity. It should also be pointed out that the rules for holding offending States responsible are preventative in nature, since they can avert other human rights violations from occurring, as we shall see below.

The Inter-American Human Rights System is notable in this context, given its role in the process of internationalizing the legal systems of various Latin American countries. The Inter-American Court of Human Rights has heard several cases of human rights violations that have led to important institutional changes in national justice systems. On this point, one issue that has gained prominence is the monitoring of the implementation, on the national level, of the decisions and recommendations that emanate from the international and regional human rights systems and mechanisms.

This being the case, the purpose of this article is to a) present a general overview of the implementation of the recommendations expressed in the 2006 judgment against Brazil in the Damião Ximenes Lopes case, the first Brazilian case heard by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, and b) to demonstrate its repercussions on the country’s public mental health policy.

According to André de Carvalho Ramos (2004), international human rights law consists of a set of rights and abilities that guarantee the dignity of the human being and that benefit from institutionalized international guarantees.

As Flávia Piovesan points out:

In response to the atrocities committed during the Second World War, the international community began to recognize that the protection of human rights constituted a legitimate international interest and concern. By becoming the subject of legitimate international interest, human rights have transcended and surpassed the preserve of the State or the exclusive national authority.

(PIOVESAN, 2006, p. 4-5).

As a result of international action, human rights violations have acquired more visibility, exposing the offending State to the risk of political and moral embarrassment, which has spurred some progress in the protection of human rights. When confronted with the publicity given human rights violations, the State is practically obligated to justify its actions, and this has helped change and improve specific government policies where human rights are concerned, providing support or incentives for domestic reforms.

When a State recognizes the legitimacy of international interventions in the field of human rights and when it alters its policy on the matter in response to international pressure, the relationship between the State, its citizens, and international actors is strengthened. The international system establishes a standard of conduct for States, making it legitimate for complaints to be lodged if international obligations are disregarded. In this vein, the international framework establishes judicial safeguards, supervision, and monitoring so that States can guarantee internationally assured human rights.

By setting minimum standards to be respected by States, the international instruments for the protection of human rights have a dual impact because they are actionable in both national and international jurisdictions. On the national level, the international instruments merge with domestic law, thereby broadening, strengthening, and streamlining the human rights protection system based on the principle of the supremacy of the human being. On the international level, the international instruments establish international safeguards by holding the State responsible when internationally assured human rights are violated.

Originally, the system of international responsibility of the State used to refer only to disputes between States. However, with the evolution of international relations, a new type of dispute in international law emerged in which the injured party was no longer the State directly, but instead a citizen of the State. Therefore, according to Patrícia Galvão Ferreira (2001), the system was broadened to protect the citizens of one State against the actions of a foreign State, starting from a 1924 jurisprudence of the Permanent Court of International Justice (the predecessor of the UN International Court of Justice), which granted permission to states to champion the cause of its nationals in international courts when they could demonstrate that the injury was caused by the breach of an international norm. Still according to the author, this understanding has preceded the current international human rights protection regime:

With the creation and ratification of international human rights treaties after the Second World War, governments radically overhauled the system of international responsibility. From this point on, international responsibility did not just protect the interests and remedy damage and injury caused by international disputes involving two States or one State against a citizen of another. Now, for the first time, international responsibility includes the State that violates an international provision that protects the rights of its own citizens.

(FERREIRA, 2001, p. 24).

Note that the objective nature of the obligations to protect human rights makes the individual the primary concern of the State’s international responsibility for human rights violations. Furthermore, André de Carvalho Ramos explains that when human rights treaties refer to the duty of the State to guarantee declared rights, they do not mention the element of “blame” to characterize the international responsibility of the State. The author states:

The jurisprudence of international human rights protection bodies is thorough in specifying the predominance of the objective theory of the international responsibility of the State. The reason for this is the need to interpret the international human rights provisions in favor of the individual, as a result of the objective nature of these rules. (RAMOS, 2004, p. 92).

Blame, therefore, is immaterial. What matters is that a human rights violation is the result of the failure either by a State directly to comply with its obligations or by persons acting with the support of the State. The basis of responsibility lies in the substantiation, pure and simple, of an action that is in breach of international law. In this vein, the same author concludes:

The international responsibility of the State for human rights violations is, undeniably, an objective responsibility. At the heart of this institution is the duty to redress that arises each time an international rule is breached. All that is needed is proof of the causal link, the conduct and the harm itself.

(RAMOS, 2004, p. 410).

Under international human rights law, the State has the primary responsibility for the protection of rights, while the international community bears the subsidiary responsibility, when national institutions present failures or omissions in the protection of rights. The main objective of the international safeguards, therefore, is to provoke advances in the national human rights protection systems.

It is important to point out that the Inter-American Court of Human Rights has developed consistent jurisprudence on the legal consequences of international responsibility for the violation of rights guaranteed by the American Convention on Human Rights. For example, article 63.1 of the convention contains a provision on the international responsibility of the State and the subsequent reparation for the harm caused.

Therefore, according to Patrícia Galvão Ferreira (2001), by ratifying the American Convention on Human Rights, States Parties to the Organization of American States (OAS) codified the principle of international law whereby a declaration of international responsibility generates the duty to restore the situation prior to the violation of the right, when possible, and redress the harm caused by the violation.

Finally, it is worth repeating the point made by André de Carvalho Ramos:

The international responsibility of the State is based on the harmful consequences and the causal link between the conduct of the State and the violation of the international obligation, with no room to investigate blame or wrongdoing by the agent or agency of the State, thereby facilitating the confirmation of State responsibility and the subsequent reparations to the individual victims of the human rights violations.

(RAMOS, 2004, p. 410).

The jurist Cançado Trindade asserts that:

As a result of the coexistence of international protection instruments based on different legal foundations […], all States (including those that have not ratified the general human rights treaties) are now subject to international supervision of the treatment of people under their jurisdiction.

(CANÇADO TRINDADE, 1998, p. 83).

This renowned author also highlights that no State today is exempt from responding to allegations of human rights violations, through their acts and omissions, before international supervisory bodies, and Brazil is no exception to this rule (CANÇADO TRINDADE, 1998).

Since the promulgation of the Federal Constitution of 1988, Brazil has ratified key international human rights treaties: the Inter-American Convention to Prevent and Punish Torture, on July 20, 1989; the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment, on September 28, 1989; the Convention on Children’s Rights, on September 24, 1990; the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, on January 24, 1992; the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, on January 24, 1992; the American Convention on Human Rights, on September 25, 1992; the Inter-American Convention to Prevent, Punish and Eradicate Violence against Women, on November 27, 1995; the Protocol to the American Convention regarding the Abolition of the Death Penalty, on August 13, 1996; the Protocol to the American Convention in the area of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (San Salvador Protocol), on August 21, 1996; the Rome Statute, which created the International Criminal Court, on June 20, 2002; the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, on June 28, 2002; the Optional Protocol to the Convention on Children’s Rights on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflicts, on January 27, 2004; and the Optional Protocol to the Convention on Children’s Rights on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography, also on January 27, 2004.

In addition to these, on December 3, 1998, the Brazilian State finally recognized the jurisdiction of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, through Legislative Decree No. 89/98. This enlarged and strengthened the jurisdictions protecting internationally assured human rights. Brazil’s alignment with the international human rights protection system is, therefore, quite recent.

Throughout this process, one key issue has been the need to combine the national and international protection systems based on the principle of human dignity, because, when this is done, the human rights assured in the national and international instruments acquire a greater importance, thereby strengthening the mechanisms for holding the State responsible.

An examination of the human rights cases in Brazil that have been referred to the Inter-American Commission (PIOVESAN, 2006) reveals that they all want international oversight, requesting an international response due to non-compliance with obligations entered into on the international level.

The same author writes: “According to international law, the responsibility for human rights violations always rests with the State, which has the legal personality on the international stage.” (PIOVESAN, 2006, p. 279). Therefore, the Brazilian State cannot invoke the federal principles or the separation of powers to absolve the federal government from responsibility for breaches of internationally agreed obligations.

Accordingly, in the case that shall be presented here, it is the Brazilian State that was judged by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, since it is the State that is held internationally responsible whenever an international human rights obligation it agreed to observe is violated (PIOVESAN, 2006).

It is important to point out, too, that the future of international human rights protection in Brazil depends in large part on national implementation measures. In addition to bringing the internal legal framework in line with international protection standards, it is also necessary to prioritize the development of public policies to guarantee and protect human rights, and also to streamline internal mechanisms for monitoring the implementation of these human rights. This underscores the subsidiary nature of international responsibility, i.e. that international action is always a supplementary action, constituting an additional guarantee of human rights protection.

It is also worth mentioning the important role of social actors in the defense and protection of human rights in Brazil, not only domestically, but also internationally, by proposing international actions before the bodies of the global and regional human rights protection systems. With the active involvement of civil society, the international instruments constitute a powerful mechanism for reinforcing the protection of human rights and the democratic regime in the country, through the designs of an engaged citizenry that is capable of uniting behind nationally and internationally assured rights and guarantees.

Maia Gelman explains Brazilian human rights activism from the standpoint of the ability to lodge complaints internationally, based on the “power to embarrass” in the realm of international relations (GELMAN, 2007). Muller, as cited byGelman, points out that “this power to embarrass is the main weapon of pressure groups that advocate for human rights. The activities of these groups are intended to influence public policy (…) and pressure the State on the international stage” (GELMAN, 2007, p. 67-68). The consequences of this international influence have been called the “boomerang effect” (GELMAN, 2007, p. 67-68). According to Keck, as cited byGelman, “this effect is triggered when a national group reaches out to foreign allies to put pressure on the government, so that it changes its domestic policies.” The author goes on to say that local governments, by ignoring the demands of these groups, can broaden the scope of their claims, causing them to echo with more resonance domestically. (GELMAN, 2007, p. 68).

On this point, Flávia Piovesan adds:

The Brazilian experience illustrates how international action can help publicize human rights violations, raising the risk of political and moral embarrassment for the offending State and, as such, causing it to emerge as a significant factor in the protection of human rights. Furthermore, when confronted with publicity on human rights violations, together with international pressure, the State is practically “compelled” to justify its actions.

(PIOVESAN, 2006, p. 313).

This is what we shall see in the case presented here, in which a complaint was lodged against Brazil with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights by the family of the victim of human rights violations.

This is the first Brazilian case to be judged by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, of the Organization of American States (OAS). Damião Ximenes Lopes, Brazilian, was 30 years old in October, 1999 when he was admitted by his mother to the only psychiatric clinic in the municipality of Sobral, in the state of Ceará. Damião was suffering from a severe mental condition, which is why his mother, Albertina Viana Lopes, took him to the aforementioned institute to receive medical attention. The clinic, called Casa de Repouso Guararapes (Guararapes Rest Home), was accredited by Brazil’s public health care service, known as the Unified Health System (SUS). Four days later, his mother returned to visit her son at the clinic and the guard refused her entrance. Despite the guard’s efforts, she managed to make her way into the institute and immediately began to call out Damião’s name. This is the report of the events that followed:

He [Damião] came to her [his mother] staggering, with his hands tied behind his back, bleeding from his nose, his head swollen and his eyes practically shut, collapsing at her feet, filthy, hurt and smelling of feces and urine. He fell at her feet crying out for her to call the police. She did not know what to do and asked that he be untied. His body was covered in bruises and his face was so swollen that he was barely recognizable.

(COMISIÓN INTERAMERICANA DE DERECHOS HUMANOS, 2004, p. 599).

Albertina then sought the help of the employees to take care of her son, and the nursing staff bathed Damião while she spoke to the only doctor who was present at the institute. Without performing any kind of examination, he prescribed Damião medication and then left the Rest Home. Albertina left the institute in a state of shock and when she arrived home, in the municipality of Varjota, she received a message that the Rest Home had telephoned. A few hours later, she returned to the institute and was informed that her son had died. The family requested an autopsy, as the doctor at the Rest Home, Francisco Ivo de Vasconcelos, had not ordered any such examination. On the same day, Damião’s body was transferred to the Dr. Walter Porto Medical Examiner’s Office, where the autopsy was performed by the same doctor from the Rest Home, who concluded that the death was from “indeterminate causes” (CORTE INTERAMERICANA DE DIREITOS HUMANOS, Caso Ximenes Lopes vs. Brasil, 2006, p. 33). However, André de Carvalho Ramos claims the autopsy report identified marks on his body that indicate torture:

Damião was subjected to physical restraint, his hands tied behind his back, and the autopsy revealed that his body had been beaten, presenting injuries located in the nasal region, right shoulder, lower portion of the knees and the left foot, ecchymosis around the left eye, homolateral shoulder and fist. On the day of his death, the doctor of the Rest Home, without physically examining Damião, prescribed him some drugs and immediately left the hospital, where there was now no doctor. Two hours later, Damião was dead.

(RAMOS, 2006, p. 1).

In response to this serious situation, Damião’s family filed a criminal case and a civil case for damages against the owner of the psychiatric clinic, and also filed a petition against the Brazilian State before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), via Damião’s sister, Irene Ximenes Lopes. Later, a Brazilian non-governmental organization that works to expose human rights violations, calledJustiça Global, joined the case as co-petitioner.

The IACHR received the petition with the allegations concerning Damião before the end of 1999 and the Brazilian State was promptly urged to present its considerations on the case. In 2000, additional information was received from Damião’s family and a new deadline was extended to Brazil to respond to the allegations. The Brazilian State once again failed to present information. The IACHR then gave the Brazilian State one final opportunity, warning that failure to respond would lead the Commission to apply the provision of article 42 of its regulations (which states that, when a government fails to respond, the facts presented in the petition will be presumed to be true).

In 2002, considering the position of the petitioner and the lack of response from Brazil, the IACHR approved the Admissibility Report, concluding that the petition met the admissibility requirements. In 2003, Brazil presented, for the first time, information on the case. In accordance with IACHR regulations, a friendly settlement procedure was made available to the parties involved. This was welcomed by the petitioner, who expected a proposal from the Brazilian State. However, no such expression was forthcoming. After additional communications and analyses of the standards of medical treatment that should be provided to people with mental illnesses, the IACHR concluded in 2003 that the Brazilian State was responsible in the Damião Ximenes Lopes case:

For violating the right to humane treatment, to life, to judicial protection and to a fair trial enshrined in articles 5, 4, 25 and 8, respectively, of the American Convention, due to the hospitalization of Damião Ximenes Lopes in inhuman and degrading conditions, the violation of his right to humane treatment and his murder, the violation of the duty to investigate and the violation of the right to effective remedies and judicial guarantees associated with the investigation of the events. The Commission also concluded that, in relation to the violation of these articles, the State also violated its generic duty to respect and guarantee the rights enshrined in the American Convention in relation to article 1(1) thereof.

(COMISIÓN INTERAMERICANA DE DERECHOS HUMANOS, 2004, p. 587).

At the same time, the IACHR recommended that the Brazilian State conduct “a full impartial and effective investigation into the events leading to the death of Damião Ximenes Lopes and make suitable reparations to his family for the violations (…) including the payment of compensation” (COMISIÓN INTERAMERICANA DE DERECHOS HUMANOS, 2004, p. 587).

In 2004, the first meeting was held between the parties involved, in which Brazil presented only partial progress in its compliance with the recommendations made by the IACHR. As a result of this, the petitioners indicated the need to refer the case to the Inter-American Court, since Brazil had not fully complied with the recommendations. The Brazilian State requested an extension, more than once, of the deadlines set by the IACHR. Considering the lack of suitable implementation of the recommendations by Brazil, the Commission decided to submit the case to the Inter-American Court.

Also in 2004, the IACHR presented an application for the Court to determine whether the Brazilian State was responsible, as previously mentioned, for violating the rights embodied in Articles 4 (dight to life), 5 (right to humane treatment), 8 (right to a fair trial) and 25 (right to judicial protection) of the American Convention in relation to the obligation established in Article 1.1 (obligation to respect rights) thereof, to the detriment of Damião Ximenes, for the inhuman and degrading conditions of his hospitalization in a psychiatric clinic that operated within the legal framework of Brazil’s Unified Health System (SUS).

The Brazilian State, in response to the notification issued by the Inter-American Court, filed a preliminary objection, claiming that not all domestic remedies had been exhausted. After reading all the written arguments on the preliminary objection (from the petitioner and from Brazil), the Court convened a hearing for November 2005. In its oral argument at this hearing, the Brazilian State acknowledged its partial responsibility for the violation of Articles 4 and 5 (right to life and a fair trial) of the American Convention, and expressed agreement with the poor treatment conditions that resulted in the death of Damião Ximenes. However, the Brazilian State did not acknowledge violation of Articles 8 and 25 of the Convention.

The Court did not accept the preliminary objection filed by Brazil, judging it to be untimely, as it should have been made earlier during the admissibility stage to the IACHR. Following the decision to dismiss the preliminary objection, the Court decided to proceed with the judgment of the case. Accordingly, the parties involved and also the IACHR submitted their final written arguments.

In 2006, the final trial on the case was held. After hearing the parties and expert witnesses, and analyzing all the documentation on the proceeding, the Court presented its judgment, sentencing Brazil for the first time in a case of merit.

According to André de Carvalhos Ramos (2006), the main points of the judgment, in addition to Brazil acknowledging the violations of articles 4 and 5 of the American Convention, were related to the fact that Damião had a mental illness and the slow pace of Brazilian justice in the criminal and civil cases brought by the family. This means that in cases of people with some form of disability, the State must not only prevent violations, but it should also take additional positive protection measures that consider the specifics of each case. On the sluggishness of the Brazilian justice system, the Court judged that the slow pace of legal proceedings encourages impunity and may be considered a violation of the right of access to justice. In the Damião Ximenes Lopes case, the lack of a trial court ruling six years after the start of the criminal case was considered a violation of the right to trial within reasonable time.

Finally, the Court determined that Brazil should make moral and material reparations to the Ximenes family, through the payment of compensation and other non-monetary measures. For example, Brazil was urged to investigate and identify those responsible for Damião’s death within reasonable time and also to implement training programs for health professionals, particularly psychiatric doctors, psychologists, nurses and nursing assistants, as well as all people working in the field of mental health.

The petition of the Ximenes Lopes family was not only the first case to be admitted and judged by the Court, as previously mentioned; it also led to the first ruling against the Brazilian State by the Inter-American system. Unlike other countries in Latin America, Brazil does not usually have many complaints filed before the Court, which likely indicates a poor knowledge of regional system in the country.

Another important point is that the judgment of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in theDamião Ximenes Lopes case is the first to address cruel and discriminatory treatment of people with mental illnesses. By recognizing the vulnerability of these people, the Court broadened international jurisprudence and, on the national level, strengthened the actions of Brazil’s Anti-Asylum Movement, which is formed by organizations that are intent on exposing human rights violations in psychiatric institutes.

According to Fabiana Gorenstein (2002), until 2002 there were only 70 Brazilian cases (either pending or shelved) in the IACHR, while neighboring Argentina had 4,000 and the Commission overall had received approximately 12,000 petitions. More recent data indicate that the number of Brazilian cases has increased. This can be seen in the research conducted by Fernando Basch et al., which measured the degree of compliance with the decisions of the Inter-American system between 2001 and 2006 (BASCH et al., 2011). In other words, the representativeness of Brazil in the Court is still small compared to the other countries that typically access the Inter-American system. This can be observed by the total number of Brazilian cases that have been heard (6), while Peru and Ecuador, over the same period (2001-2006), had 17 cases each (Basch et al., 2011). Another factor that should be taken into consideration is the size of the Brazilian population, which – even though comparatively far higher than all the other Latin American countries – does not translate into a larger number of filings with the Inter-American system. In fact, Brazil has fewer filings than countries that have significantly smaller populations.

Therefore, the judgment against Brazil in the Damião Ximenes Lopes case serves as an example to be followed, since it demonstrates that efficient international mechanisms exist that protect rights and adequately redress the victims of human rights violations. The case can also be considered a success because the complaint filed by the family was heard and Brazil was sentenced for serious human rights violations. In other words, this case serves as a model in a culture unaccustomed to claiming rights on the international level.

Even before the final ruling of the Court, significant progress was already underway in Brazil, reflecting the positive repercussions of the case. Foremost among these advances: the Guararapes Rest Home, where Damião died, not only had its accreditation as a psychiatric institute that provides services to Brazil’s Unified Health System (SUS) revoked in July 2000, but it was also shut down nearly a year after the incident.

Furthermore, a lifelong annuity was granted to Damião’s mother by the state of Ceará in 2004 and a new health center was opened, called Damião Ximenes Lopes, as part of the new mental health policy established by Law No. 10216/2001 (BRASIL, 2001).

According to Ludmila Correia, the municipality of Sobral is now considered a reference in mental health, because it prioritizes residential therapy and/or outpatient care, abandoning treatment that involves confinement. Indeed, the municipality has received an award for the successes it has achieved with its new policy (CORREIA, 2005).

Following the ruling against Brazil, the federal government was urged to pay compensation to Damião’s family, given that moral and material damage had been proven, and also to pay the court costs incurred in the case. As a result, on August 14, 2007, the Brazilian State made the payment of the amounts set by the ruling to Damião’s family in accordance with Decree No 6185 of August 13, 2007 (BRASIL, 2007).

Concerning the investigations into those responsible for Damião’s death, only in 2009 were the owner of the Guararapes Rest Home and six members of staff sentenced to serve six years in a semi-open prison (CORTE INTERAMERICANA DE DIREITOS HUMANOS, Caso Ximenes Lopes vs. Brasil, 2009).

In 2010, in a civil case for moral damages brought by the Ximenes Lopes family, the Ceará State Court of Appeals upheld the trial court ruling that sentenced the owner of the psychiatric clinic and also the clinical director and the administrative director to pay compensation in the amount of R$150,000 to Damião’s mother. It is interesting to note that, in the proceedings of this case, there is a copy of the IACHR Report that led to the judgment against Brazil. This demonstrates the repercussions of the international ruling on domestic law, according to information obtained from the Ceará State Court of Appeals website. On this point, it is worth noting the reflections of Víctor Abramovich on how international law impacts a country’s domestic legal affairs in a dynamic way and in line with local characteristics:

At the same time, these international norms are incorporated into national legislation by the respective Congresses, governments and judicial systems, and also with the active participation of social organizations that promote, demand and coordinate the domestic application of international norms before various state organs. The application of international norms on the national level is not a mechanical act, but rather a process that involves different kinds of democratic participation and deliberation and provides ample room for a rereading or reinterpretation of the principles and international norms in accordance with each national context.

(ABRAMOVICH, 2009, p. 25).

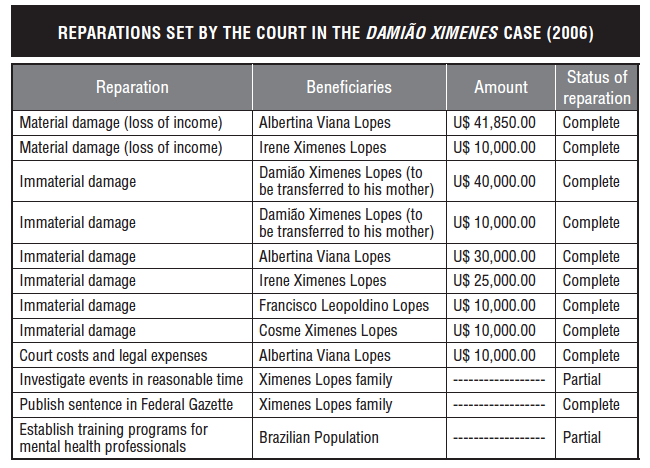

The table below shows each of the individual reparation measures applied by the Court, the beneficiaries, the amounts (for monetary reparations) and the status of compliance with the measure, for the current year [2011].

Finally, it is clear that the solution of the case was slow in terms of domestic law. Both in the criminal and civil case, the family had to wait more than 10 years for a trial court verdict sentencing the perpetrators in the criminal case and to receive the reparation for moral damages due to the death of Damião Ximenes. At the same time, the Court, in its Order on the Monitoring of Compliance with the Judgment, asserted that due to “the possibility that motions may be filed against the aforementioned decision, Brazil should submit, in its next brief, thorough and updated information on the status of the criminal proceedings” (CORTE INTERAMERICANA DE DIREITOS HUMANOS, Caso Ximenes Lopes vs. Brasil, 2009, p. 4-5). For this reason, compliance with this measure is considered to have been partial, not only because the family had to wait 10 years for a trial court verdict, but also, and primarily, because it was not a final judgment, meaning that the defendants can appeal.

This situation confirms the thesis of Víctor Abramovich, when analyzing the Inter-American system, that the implementation of international decisions, on the domestic level, encounters the following difficulties:

Complying with the reparation measures issued by an international organ requires a high level of coordination between governmental agencies, which is often not achieved. This significantly hampers the processing of the case, the work of the ISHR’s organs, and the enforcement of decisions. Effectively coordinating between agencies even within the same government is complex, and even more so when the government must coordinate its activities with Parliament or the judicial system, when the measures involved in a case require legal reforms or the filing of lawsuits.

(ABRAMOVICH, 2009, p. 26-27).

However, it can be said that the investment made by the family in its claim before the IACHR yielded several positive results. First, the Brazilian State was held responsible internationally for violating human rights, which was unprecedented in the country. Additionally, compensation for material and immaterial damages was paid to the family for Damião’s death. Finally, the Brazilian State was urged to review its policy, coming under pressure to make important changes to its mental health policy on the legislative and administrative levels, and also in the overall provision of services, which will be examined next.

The National Mental Health Policy has been the subject of reform recently in Brazil: a new perspective in the country’s legal framework in relation to people with mental illness led to the approval of Law No. 10216, on April 6, 2001 (BRASIL, 2001). This special legislation provides for “the protection and the rights of people with mental illness and redirects the model of mental health care,” making the State and society responsible for shifting away from the previous model of care that was based exclusively on traditional confinement. The introduction of this new policy establishes the paradigm of co-responsibility of society and the State, based on intersectoral actions that are not limited to the health sector.

The new law was finally approved after 12 years of stalemate in the National Congress, indicating that the Damião Ximenes case contributed to speeding up the passage of the law, as Brazil responded to the international pressure exerted by the IACHR in 1999. This can be observed from the arguments made in defense of the Brazilian State before the Court, by the National Mental Health Coordinator at the time, Pedro Gabriel Godinho:

In 2001, Law No. 10216 was passed, intended to defend the rights of mental patients, change the model of care at facilities such as the Guararapes Rest Home into a community-based care network and establish an external oversight of involuntary psychiatric admissions, under the terms of the UN Principles for the Protection of Persons with Mental Illness of 1991.

(CORTE INTERAMERICANA DE DIREITOS HUMANOS, Caso Ximenes Lopes vs. Brasil,2006, p. 16).

The new mental health model established after the approval of the law consists of a network of daily treatment services in Brazil formed primarily by Psychosocial Treatment Centers (CAPS), which are intended to integrate the users of these services with their families and the community. The CAPS facilities constitute the cornerstone of the strategy pursued by the Ministry of Health to reform public mental health care in Brazil. The reform actually began with the very first Psychosocial Treatment Units and Centers in the 1980s, but was propelled by the approval of the new law and the implementation of the new mental health policy by the Brazilian State.

The standards and guidelines for the functioning of the CAPS are contained in Decree No. 336/GM of February 19, 2002, and they are classified by the size of the facility and the type of patient, and given the denominations CAPS I, CAPS II, CAPS III, CAPSi and CAPSad. Moreover, Decree No. 189 of March 20, 2002, established a new funding system for the procedures that can be charged by the CAPS facilities that are registered with the Unified Health System (SUS). In addition to the CAPS, the mental health care network consists of other services, such as outpatient facilities and extended care clinics, day hospitals, Residential Therapeutic Services (SRT), the Return Home Program, Communal Centers, beds reserved in general hospitals, and beds in psychiatric hospitals.

In 2003, in the area of Basic Care, the Ministry of Health released the document “Mental Health and Basic Care: the connection and the dialogue necessary,” which stresses the importance of prioritizing training in the development of the new policy and including mental health indicators in the Basic Care Data System (SIAB) in order to evaluate and plan actions in this area (BRASIL, 2003). Additionally, the Ministry of Health also issued Decree No. 154 in 2008 that created the Family Health Support Centers (NASF). Among the provisions contained in this Decree is the recommendation for each NASF to have at least one mental health professional, given the “epidemiological magnitude of mental illnesses” (BRASIL, 2008, p. 3). Concerning mental health actions, this document stipulates that the NASFs should be integrated with the mental health care network (that includes the Basic Care/Family Health network, CAPS, Residential Therapeutic Services, outpatient facilities, communal centers and leisure clubs, among others), “organizing their activities based on the demands identified together with the Family Health staff, helping create the right conditions for the social reintegration of the users and maximizing the potential of the community resources (…)” (BRASIL, 2008, p. 10-11).

In the face of these new provisions, the need arises to examine how they have been implemented in Brazil and whether they assure mental health patients the right to treatment and universality of access, which are guaranteed by the Federal Constitution and the SUS. The decentralization of the treatment is another principle of the new model, as the services are organized closer to the social environment of their users, with the care networks paying more attention to existing inequalities and tailoring their actions to the needs of the population in an equitable and democratic manner.

In a number of publications and information systems, the Ministry of Health releases data on the implementation of the mental health network in Brazil. For the purposes of this article, data was taken in July of this year from the Ministry of Health’s electronic report Mental Health in Data – 7, which is an important source of national data.

The number of CAPS installed across the country, in June 2010, had reached a 63% coverage rate (considering the recommended minimum of one CAPS for every 100,000 inhabitants). It is worth noting that coverage in the Northeast of Brazil has improved from “critical” in 2002 to “very good” in 2009. Other regions, however, particularly the North of the country, require special attention because of their specific characteristics (BRASIL, 2010).

The coverage of residential therapeutic facilities is still considered low. According to the aforementioned electronic report, the factors holding back the expansion of these services are:

Insufficient funding mechanisms, political difficulties with deinstitutionalization, poor liaisons between the SRT program and the federal and state housing programs, local resistance to the process of social and family reintegration for long-time patients and the fragility of continued training programs for the residential services staff. (…)

(BRASIL, 2010, p. 11).

This being the case, the Brazilian government needs to develop an appropriate system of funding that involves different sectors of public policy besides just health, and also establish the criteria and guidelines to cater to the needs of people with mental illness who are either homeless, who are still inpatients, or who have been released from psychiatric hospitals. Furthermore, it is necessary to rethink the structure of the residential therapeutic facilities, taking into consideration the characteristics and needs of the public that will be treated, accounting for matters such as age and length of internment, among other things.

Another provision that has proven difficult to implement and consolidate is the Return Home Program, as can be observed from the number of people who have benefited in Brazil. According to the Ministry of Health’s report (BRASIL, 2010, p. 12), “only one third of the estimated number of people held in hospitals for long periods receive the benefits,” which demonstrates the failure of some sectors to realize a genuine process of deinstitutionalization, to ensure the necessary documentation for mental health patients, to effectively reduce the number of psychiatric beds and to streamline the lawsuits in which this social group figures as a party.

Also relevant is the low number of Communal Centers in place in Brazil, since these centers play a significant role in the current model of mental health care (BRASIL, 2010).

In the case of mental health outpatient facilities, the situation is also problematic, considering that, in general, these services produce poor results and their work is not well integrated with the wider mental health care network, and so a more in-depth discussion is required about their role in Brazil’s current mental health policy (BRASIL, 2010).

On the matter of psychiatric hospitals, there has been a progressive reduction in the number of beds between 2002 and 2009, with 16,000 beds being eliminated by the psychiatric division of the National Hospital Services Assessment Program (PNASH) and the Program for the Restructuring of Psychiatric Care (PRH). However, despite the changing profile of these hospitals (they have grown smaller: 44% of the beds are now in small hospitals), Brazil still has 35,426 psychiatric beds (BRASIL, 2010). In this case, it is vital to reflect on the hospital-based model that still persists in the country, despite the implementation of regional and community services.

The number of beds reserved in general hospitals in Brazil, meanwhile, totaled just 2,568 in July 2008 (BRASIL, 2010). This number represents a major setback in the implementation of psychiatric reform in Brazil, which is intended to focus mental health care on a regional level, gradually closing down psychiatric hospitals and placing psychiatric beds in general hospitals in order to provide more complex care in this area.

Concerning the role of mental health professionals at the NASFs opened in Brazil, the Ministry of Health’s report reveals that in April 2010, these professionals represented 2,213 of the 6,895 employees at these centers, which corresponds to approximately 30% of the total (BRASIL, 2010).

It should be added that, although there have been a series of advances in mental health policies in the country, the Brazilian State has still not adopted specific training programs for mental health professionals, particularly in psychiatric hospitals (which was determined by the Court), indicating the fragility of the country’s mental health care network. Therefore, the Brazilian State needs to be urged by the IACHR to resolve this matter, which is still pending, that has been monitored by the NGO Justiça Global.

Furthermore, there are still cases of deaths at some psychiatric hospitals in Brazil as a result of mistreatment and violence perpetrated against patients there, reaffirming that these facilities continue to violate human rights, according to information from the website of the Mental Health and Human Rights Monitoring Center and the Anti-Asylum Movement. These organizations also confirm that that there is no national system of oversight, while communication and the exchange of information within the network on all these issues is still flawed.

Finally, it is worth noting that the Ministry of Health and the Special Ministry of Human Rights issued Interministerial Decree No. 3347 of September 29, 2006, that established the Brazilian Center for Human Rights and Mental Health, which was formulated by a Working Group created especially for this purpose by the two ministries. The Decree sets the guidelines and courses of action for the Center, in accordance with the proposals made in the Final Report of the Working Group, for it to be:

An initiative that is intended to broaden the channels of communication between the public authorities and society, through the formulation of a mechanism for lodging complaints and externally monitoring the institutions that treat people with mental illnesses, including children and adolescents, people with alcohol and other drug abuse related illnesses, and also people in confinement.

(BRASIL, 2006).

However, despite the fact that it has been open for almost five years, there is only one official record of activity by the Center since its creation. In April this year [2011], a group of institutions led by the Federal Psychology Council staged an inspection of psychiatric hospitals in the city of Sorocaba, in the state of São Paulo, after receiving complaints of human rights violations. The Brazilian Center for Human Rights and Mental Health was involved in this inspection, sending one member of its executive committee, according to information obtained on the website of the Federal Psychology Council.

Even considering the aforementioned progress in the country’s mental health policy, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights determined, in its Order on the Monitoring of Compliance with the Judgment, that the training of mental health professionals constitutes a measure with which Brazil has still not complied (CORTE INTERAMERICANA DE DIREITOS HUMANOS, Caso Ximenes Lopes vs. Brasil,2009). Accordingly, the Court requested that the Brazilian State, on the subject of training mental health professionals, specifically address the following matters:

It is necessary for the State to refer in its next brief solely and exclusively to: i) the training activities carried out after the decision, whose content refers to “the principles that must govern the treatment given to individuals with mental disabilities pursuant to international standards on the subject and those set forth in the […] Judgment”, ii) the duration, periodicity and number of participants in those activities, and iii) whether they are mandatory.

(CORTE INTERAMERICANA DE DIREITOS HUMANOS, Caso Ximenes Lopes vs. Brasil,2009, p. 7).

The monitoring conducted by the Court on the compliance with the judgment, in the case in hand, demonstrated that, in spite of the improvements identified in Brazil’s mental health policy, there is still a great deal of progress to be made. Not only are deaths continuing to occur in psychiatric hospitals similar to the one that held Damião Ximenes, but the numbers presented on the replacement services (CAPS, Residential Therapeutic Facilities, Communal Centers, etc.) are still insufficient to meet the demands of the population. This situation confirms that a hospital-based model of mental health care still remains in place in Brazil and this cannot be left unaddressed.

By adhering to the international human rights protection system, together with the obligations that come with it, the State also accepts international monitoring of how fundamental rights are respected in its territory. It is, therefore, reaffirming the general principle of international law, according to which the violation of international rules applicable to States generates international responsibility for the offending State.

It could be said that the need to provide an effective guarantee of human rights leads to a broadening and a deepening of the dual responsibility of prevention and punishment that the State has over all individuals in its jurisdiction. The obligation of a “guarantee” finally makes the State face its responsibilities both in relation to its agents or employees who are “outside the law,” and also in relation to private individuals.

An important observation can be made about the verdicts issued by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in the cases it hears. It can be said that the Court has contributed actively and consistently to the improvement of the system of international responsibility, encouraging States to increasingly pursue the international protection of human rights. Although the jurisprudence of the Court is still quite recent, the Inter-American system is turning into a relevant and effective strategy for the protection of human rights when national institutions are currently failing.

On this point, we should highlight the importance of the monitoring – by the Inter-American Commission and by States Parties to the American Convention – of compliance with the Commission’s recommendations to States that are being held internationally accountable and with the rulings of the Court. The effective oversight of compliance with the recommendations of the Commission and the decisions of the Court by the States Parties to the Convention is consistent with the overarching goal of international human rights law, which is to achieve the effective protection of human rights. Note that the monitoring of State conduct has a preventative effect.

It should be pointed out that the progress in the field of international human rights law is due largely to the growing awareness and mobilization of civil society, together with the sensitivity of public institutions towards the prevalence of human rights. Furthermore, the international protection instruments constitute powerful mechanisms to effectively strengthen the protection of human rights on the national level by reasserting the importance of the domestic protection mechanisms.

The compliance of the Brazilian State with the ruling in the Damião Ximenes case raises a number of considerations about the monitoring of the implementation, on the national level, of the decisions and recommendations that emanate from the Inter-American Human Rights System.

While Brazil may have complied almost in full with the judgment and, more specifically, while progress has been made in the new model of mental health care in the country, it is important to adopt measures and mechanisms for receiving and investigating complaints on mistreatment and violence committed against people with mental illnesses, with an emphasis on the participation of organized civil society (as provided for in the Brazilian Center for Human Rights and Mental Health), the Public Prosecutor’s Office, and organizations representing health sector professionals, to create a channel of communication between users of mental health services and their families and to restrict conduct that violates the rights of people with mental illnesses.

According to Brazil’s Anti-Asylum Movement, the replacement network of mental health services should offer quality treatment that caters to the demands of the Brazilian population, thereby demonstrating comprehensive psychiatric reform. Moreover, the underlying principles of these services should be very clear in order to strengthen the significance of the social environment of the users, taking into account that many CAPS facilities end up reproducing the atmosphere of an asylum in their daily treatment.

Therefore, one of the major challenges in the area of mental health affecting public policy on the rights of this social group is the socio-cultural dimension, in the sense that it is only possible to talk about changes to the model if effective actions are in place to transform society’s attitude towards people with mental illness.

Given everything that has been expressed here, there is no doubt that the formulation of rules to guarantee the quality of mental health treatment in Brazil gained momentum with the Psychiatric Reform Law in 2001, together with the other rights protection mechanisms that derived from it, as a result of the mobilization of the Brazilian State in the wake of the Damião Ximenes case.

Bibliography and Other Sources

ABRAMOVICH, V. 2009. Das violações em massa aos padrões estruturais: novos enfoques e clássicas tensões no Sistema Interamericano de Direitos Humanos. Sur – Revista Internacional de Direitos Humanos, São Paulo, n. 11, v. 6, dez. 2009. Available at: <http://www.surjournal.org/conteudos/pdf/11/01.pdf>. Last accessed on: May 6, 2011.

BASCH, F. et al. 2010. A eficácia do Sistema Interamericano de Proteção de Direitos Humanos: uma abordagem quantitativa sobre seu funcionamento e sobre o cumprimento de suas decisões. Sur – Revista Internacional de Direitos Humanos, São Paulo, n. 12, v. 7, jun. 2010. Available at: <http://www.surjournal.org/conteudos/pdf/12/02.pdf>. Last accessed on: May 4, 2011.

BRASIL. 2001. Lei nº 10.216, de 6 de abril de 2001. Dispõe sobre a proteção e os direitos das pessoas portadoras de transtornos mentais e redireciona o modelo assistencial em saúde mental. Diário Oficial [da] República do Brasil, Poder Executivo, Brasília, DF, 9 abr. 2001.

______. 2003. Ministério da Saúde. Coordenação Geral de Saúde Mental e Coordenação de Gestão da Atenção Básica. Saúde Mental e Atenção Básica: o vínculo e o diálogo necessários. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde. Available at: <http://portal.saude.gov.br/portal/arquivos/pdf/diretrizes.pdf>. Last accessed on: June 28, 2008.

______. 2004. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Departamento de Ações Programáticas Estratégicas. Saúde mental no SUS: os centros de atenção psicossocial. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde.

______. 2006. Portaria Interministerial nº 3.347, de 29 de dezembro de 2006. Institui o Núcleo Brasileiro de Direitos Humanos e Saúde Mental. Diário Oficial [da] República do Brasil, Poder Executivo, Brasília, DF, 2 jan. 2007. Available at: <http://dtr2001.saude.gov.br/sas/PORTARIAS/Port2006/GM/GM-3347.htm>. Last accessed on: July 20, 2011.

______. 2007. Decreto nº 6.185, de 13 de agosto de 2007. Autoriza a Secretaria Especial dos Direitos Humanos da Presidência da República dar cumprimento à sentença exarada pela Corte Interamericana de Direitos Humanos. Available at: <http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2007-2010/2007/Decreto/D6185.htm>. Last accessed on: May 6, 2011.

______. 2008. Ministério da Saúde. Portaria nº 154, de 24 de janeiro de 2008. Cria os Núcleos de Apoio à Saúde da Família – NASF. Brasília.

______. 2010. Ministério da Saúde. Saúde Mental em Dados – 7, Brasília, ano V, n. 7, jun. Informativo eletrônico. Available at: <http://portal.saude.gov.br/portal/arquivos/pdf/smdados.pdf>. Last accessed on: July 20, 2011.

CANÇADO TRINDADE, A.A. 1997. Tratado de direito internacional dos direitos humanos. Porto Alegre: Sergio Antonio Fabris. v. I e II. ______. 1998. A proteção internacional dos direitos humanos e o Brasil. Brasília: Fundação Universidade de Brasília.

CONSELHO FEDERAL DE PSICOLOGIA. Comissão de Direitos Humanos do CFP participa de inspeção em hospitais psiquiátricos de Sorocaba (SP). POL – Psicologia Online, 29 abr. Available at: <http://www.pol.org.br/pol/cms/pol/noticias/noticia_110429_001.html>. Last accessed on: May 4, 2011.

CORREIA, L.C. 2005. Responsabilidade Internacional por Violação de Direitos Humanos: o Brasil e o Caso Damião Ximenes. In: LIMA JR, J.B. (Org.). Direitos Humanos Internacionais: perspectiva prática no novo cenário mundial. Recife: Bagaço.

FERREIRA, P.G. 2001. Responsabilidade Internacional do Estado. In: LIMA JR., J. B. (Org.) Direitos Humanos Internacionais: avanços e desafios no início do século XXI. Recife.

GELMAN, M. 2007. Direitos humanos: a sociedade civil no monitoramento. Curitiba: Juruá.

GORENSTEIN, F. 2002. O Sistema Interamericano de Proteção dos Direitos Humanos. In: LIMA JR, J.B. (Org.). Manual de Direitos Humanos Internacionais. Recife.

OBSERVATÓRIO DE SAÚDE MENTAL E DIREITOS HUMANOS. Casos de mortes/violações de direitos humanos. Available at: <http://osm.org.br/osm/casos/>. Last accessed on: July 28, 2011.

PIOVESAN, F. 2006. Direitos humanos e o direito constitucional internacional. 7. ed. São Paulo: Saraiva.

RAMOS, A.C. 2004. Responsabilidade internacional por violação de direitos humanos. Rio de Janeiro: Renovar.

______. 2006. Reflexões sobre as vitórias do caso Damião Ximenes. Available at: <http://www.conjur.com.br/2006-set-08/reflexoes_vitorias_damiao_ximenes>. Last accessed on: May 6, 2011.

TRIBUNAL DE JUSTIÇA DO CEARÁ. Caso Damião: Justiça condena envolvidos a pagar R$ 150 mil de indenização. Available at: <http://www.tjce.jus.br/noticias/noticias_le_noticia.asp?nr_sqtex=17312>. Last accessed on: May 6, 2011.

Jurisprudence

COMISIÓN INTERAMERICANA DE DERECHOS HUMANOS. 2004. Demanda en el Caso Damião Ximenes Lopes (Caso 12.237) contra la República Federativa del Brasil. 1 out. Available at: <http://www.corteidh.or.cr/docs/casos/ximenes/dcidh.pdf>. Last accessed on: May 6, 2011.

CORTE INTERAMERICANA DE DIREITOS HUMANOS. 2006. Caso Ximenes Lopes vs. Brasil. Sentença de 04 de julho de 2006. Mérito, Reparações e Custas. Available at: http://www.corteidh.or.cr/docs/casos/articulos/seriec_149_por.pdf. Last accessed on: May 6, 2011.

______. 2009. Caso Ximenes Lopes vs. Brasil. Resolução de 21 de setembro de 2009. Supervisão de cumprimento de sentença. Available at: <http://www.corteidh.or.cr/docs/supervisiones/ximenesp.pdf>. Last accessed on: May 6, 2011.