Turning quantitative data into a tool for human rights accountability

In spite of positive developments in the last 60 years, the worldwide promotion and protection of economic and social rights remains a daunting challenge. While millions of people are deprived of clean water, primary health care and basic education, most states do not recognize economic and social rights as more than abstract declarations of principles. Also, governments and international organizations usually tackle these questions exclusively as development challenges, ignoring their relation to human rights obligations. In this article, there is an initial attempt to set out a methodological framework to illustrate how some simple quantitative methods can be used in concrete situations to assess whether a state is violating its human rights obligations. Quantitative tools can help us, as human rights advocates, not only to persuasively show the scope and magnitude of various forms of rights denial, but also in revealing and challenging policy failures that contribute to the perpetuation of those deprivations and inequalities.

Milestones are often an occasion for introspection. This year the international community is celebrating the 60th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It is also 15 years since the UN World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna, in which all States affirmed the indivisibility and interdependence of human rights and called for renewed efforts to ensure recognition of economic, social and cultural rights at the national, regional and international levels.

This is therefore a timely opportunity to assess the progress made in the field of economic and social rights since then. The international community has given increasing recognition to the indivisibility and interdependence of all human rights: civil, political, economic, social and cultural. At the same time, extraordinary progress has been made by academics and human rights advocates in articulating both the content of economic, social and cultural rights (ESC rights), and the nature of the corresponding state obligations.

In spite of these positive developments, the worldwide promotion and protection of economic and social rights remains a daunting challenge. While millions of people are deprived of clean water, primary health care and basic education, most states do not recognize economic and social rights as more than abstract declarations of principles. When governments and international organizations address problems of health, education, clean water and housing, they usually tackle these exclusively as development challenges, ignoring their relation to human rights obligations. This was the case over a decade ago at the World Summit for Social Development and is still the case today, as demonstrated by the Millennium Development Goals, to which links to human rights have been made only as an after-thought.

The limited inroads human rights advocates have made in development debates is in part due to states’ reluctance to accept legal accountability in areas of economic and social policy. But the failure of the human rights movement to develop effective monitoring tools in this field may also be a contributing factor.

Developing rigorous monitoring tools has been an uphill battle for human rights advocates working on economic and social rights. A major obstacle in developing such tools has been the manner in which state obligations have been defined with respect to economic and social rights. Under international law, states are required to take steps “with a view to achieving progressively the full realization” of economic and social rights “to the maximum of their available resources”.2

Some state obligations of immediate effect have also proven difficult to monitor. These include core obligations to ensure at least “minimum levels” of enjoyment of the essential elements of economic and social rights, such as access to essential foodstuffs, basic health care and primary education.3 Another is the obligation to guarantee the exercise of rights without discrimination, particularly to reduce disparities resulting from the unfair distribution of goods and services.

Monitoring these various dimensions of state obligations requires a methodology not based exclusively on qualitative research; the methodology should also include quantitative tools. These tools are not typically part of human rights organizations’ research toolkits, which in many cases were originally developed to monitor civil and political rights.4 As Michael Ignatieff and Kate Desormeau point out,

Even where relevant data is available over time we are uncertain how to interpret it, how to use it to guide our human rights arguments. Many practitioners are unsure how to conduct their own studies; many too are uncertain where to find relevant statistics and unsure what to do with them once they have found them.5

Given the difficulties of monitoring the dimensions of ESC rights obligations that require the use of quantitative tools, measuring progressive realization according to maximum available resources, both the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) and human rights NGOs have usually refrained, when monitoring specific countries, from addressing issues of ESC rights that are bound to the requirements of progressive achievement and resource constraints,6 focusing instead on various immediate obligations related to ESC rights which are not dependent on resource availability.7 These obligations include the duty to respect, which requires the state to refrain from interfering with people’s exercise of a right; the duty to protect, which requires the state to ensure that third parties do not interfere, primarily through effective regulation and remedies,8 as well as the most tangible aspects of the duty to guarantee the exercise of rights without discrimination,particularly discrimination formally enshrined in law or discriminatory practices carried out by public officials, such as doctors, teachers, etc.

For example, in recent years, international NGOs have documented violations such as denying access to health and education for minority communities,9 failing to enact or enforce laws on women’s property rights,10 carrying out arbitrary forced evictions,11 or restricting humanitarian agencies’ access to refugee camps to deliver food in emergencies.12

While this focus has been effective in many ways, sidestepping the standards of resource availability and progressive realization – and to some extent, also the standard of minimum core obligations –13 have severely constrained the ability of the human rights movement to address broader issues of public policy that have a huge impact on the realization of ESC rights. Millions of people around the world are victims of avoidable deprivations such as illiteracy, preventable diseases, malnutrition and homelessness, which are not necessarily the result of interference by the State or third parties in the exercise of their ESC rights. These avoidable deprivations cannot be attributed to violations of the duties to respect or protect human rights. Nevertheless, whether these people can enjoy their ESC rights often depends on whether they have access to adequate health care or quality education and these largely (albeit not only) depend on the availability of resources.14

Moreover, without a monitoring methodology to address these crucial issues, advocacy efforts are severely undermined. Governments can easily claim, for instance, that the lack of progress is due to insufficient resources when, in fact, the problem is often not the availability, but rather the distribution,of resources.

In recent years, there has been a growing recognition of the value of using indicators for human rights monitoring.15 The idea has been the subject of numerous international academic conferences and a myriad of articles. Meanwhile, the UN human rights machinery has increasingly called for the production and use of human rights indicators, and various UN human rights mechanisms have responded by laying out a set of indicators to monitor compliance with human rights norms pertaining to economic and social rights.16

All these efforts have helped lay the groundwork for using quantitative data to monitor ESC rights. In particularly, these efforts have contributed to clarifying the potential benefits of applying indicators for monitoring economic and social rights, setting out a typology for the development and selection of human rights indicators and proposing specific indicators related to specific rights.

However, despite all this progress made at the conceptual level, these various sets of proposed indicators have only rarely been used in the assessment of specific countries.17 So far, there are more conferences and articles about human rights indicators than actual use of indicators in monitoring the compliance of a specific state on ESC rights.

What may be missing to turn indicators into an operational tool to monitor economic and social rights in specific situations is a methodology toolbox that would explain more specifically how and when to use these indicators. Much the same way as having a grocery shopping list is not sufficient to make a meal, having a list of human rights indicators is not sufficient to assess compliance. As with cooking, what is also needed is a set of recipes, or a toolbox of simple methods that explains how indicators could be used in order to assess the compliance of specific countries with regard to the multiple dimensions of rights obligations. Only after such tools are developed, will it be possible to actually apply the multiple sets of indicators that have been proposed in recent years to monitoring specific rights in specific countries.

In the remaining of this article, I will make an initial attempt to set out a methodological framework for this toolbox and to illustrate how some simple quantitative methods, both alone and combined with qualitative research, can be used in concrete situations to assess whether a state is violating its human rights obligations. The quantitative tools presented in this article are just a few examples of the Center for Economic and Social Rights’ current efforts to develop a methodological toolbox to monitor economic and social rights. At this stage this toolbox is being developed for only two rights – the right to education and the right to health – both because they are prominent in many monitoring and advocacy efforts and because these are two areas of public policy related to ESC rights in which there is more data available. It should be stressed that the tools presented here reflect only the initial efforts in developing the toolbox. They are illustrations of a work in progress and should be treated as such. CESR invites critiques of the underlying assumptions, methodological tools and conclusions in order to correct or refine the tools for future use.

Talk of quantitative tools may raise some concern among many human rights advocates that what is proposed in this article is a set of complicated methods that are beyond the reach of most human rights NGOs or international monitoring mechanisms and that they turn human suffering and injustice into rarefied statistical techniques, thereby diminishing the potential of numbers as a powerful advocacy tool. But quantitative methods do not necessarily have to be complex in order to be effective monitoring and advocacy tools. To take the cooking analogy further, just as it is possible to make both sophisticated and simple food recipes, it is also possible to measure states’ efforts to comply with their human rights obligations using either sophisticated tools (such as benefit incidence analysis, public expenditure tracking surveys or complex costing exercises) or simple tools.

Accordingly, this article presents some simple quantitative tools based on descriptive statistics that any human rights advocate could use without advanced technical knowledge.

Before discussing the specific tools that can be used to monitor ESC rights, it is necessary to clarify some conceptual and methodological issues related to the nature of human rights indicators and to the various purposes for which they could be used.

The differences between the various frameworks proposed to use indicators in the monitoring of economic and social rights might be partially attributed to differences in conceptual and methodological premises, but it is also related to the different end goals of each of these initiatives. In the field of economic and social rights, as in other fields, indicators and data are often used for more than one purpose and by more than one type of user (be it an organization or an individual).

For example, the quantitative tools that a UN Human Rights Treaty Body would use to monitor compliance with an international convention would probably be very different than those used by an international development agency interested in assessing human rights progress by individual countries to help them determine their aid priorities.18 Furthermore, the use of quantitative tools by a government committed to integrating human rights principles into its public policies19 would be quite different than that of an advocacy human rights NGO that is interested in exposing, and perhaps “naming and shaming,” a government that is unwilling to adopt policies in line with its human rights obligations.

The tools presented here are meant primarily to serve national and international NGOs as well as international monitoring bodies to monitor compliance of state obligations related to economic and social rights. Nevertheless, it is our hope that the tools will also serve other users and might be adapted for different purposes.

Most indicators proposed by various authors to monitor ESC rights are in fact development indicators, commonly used by international agencies such as the World Bank, UNICEF or WHO to monitor and conduct research on issues such as health, education and food security. This is not only the case with ’outcome indicators’ which measure the extent to which a population enjoys a specific right such as chronic malnutrition rates or illiteracy rates, but also with ’process indicators,’ measure various types of efforts being undertaken by the State, as the primary duty-holder of ESC rights, in implementing its obligation, such as the proportion of births attended by health skilled personnel.20 Both of these types of indicators are the bread and butter of any analysis done by development economists, epidemiologists and other social scientists who conduct public policy research and analysis.

Although indicators to monitor ESC rights might be the same ones commonly used in the field of development, it is the purpose for which they are used that can transform indicators such as child mortality rates or pupil-teacher ratios into genuine human rights indicators. This purpose should reflect the unique contribution that a human rights perspective can bring to the development field.

It is widely recognized that one of the key contributions of a human rights perspective to the development field is its focus on accountability.21 Human rights can help hold national governments – the primary duty bearer of human rights – accountable for avoidable deprivations of basic needs.

Clearly, there are numerous reasons why millions of people around the world are deprived of basic education, health care, shelter or food. Some of these reasons, such as natural disasters, humanitarian crises or scarcity of resources are often beyond the control of governments, and as such, cannot be deemed human rights violations. Nonetheless, using a human rights approach calls attention to the fact that widespread deprivations are all too often not inevitable; rather, they are frequently generated or exacerbated by the lack of political will of governments

A government’s failure to prevent or rectify avoidable deprivations can take many forms. In some cases, these failures are the result of deliberate policies of government agents, such as corrupt practices that reduce the resources available for the progressive achievement of economic and social rights, or discriminatory distribution of social services resources, for example providing less to those areas where the majority of people belong to an ethnic minority group. In other cases, marginalized groups are deprived of programs and resources they need to enjoy their economic and social rights simply as the result of the willful indifference of political and economic elites.22

Addressing avoidable deprivations in food security, health care, education or housing is crucial to making economic and social rights relevant to ordinary people around the world, as a primer by Amnesty International on this set of rights aptly puts it: “Much skepticism about economic, social and cultural rights is the result of feelings of helplessness or resignation in the face of overwhelming statistics on deprivation”.23

The overarching challenge is how to distinguish between deprivations that are the result of factors beyond the control of national governments, and deprivations in which government policies are a major contributing, if not causal, factor. In other words, one must distinguish between cases in which governments are unable to meet their duties and those in which governments lack the political will to do so.24

Quantitative tools can play a crucial role in holding governments accountable for policies and practices which lead to avoidable deprivations, thus breaching their human rights obligations. Such tools could help assess whether high levels of deprivations or inequalities in the fields of education, health, housing, and food security are created, perpetuated or exacerbated by specific actions or omissions25 of state policy.

To be able to analyze data for monitoring economic and social rights, it is not sufficient to have only a set of indicators. Data about a sole indicator generally does not indicate much. For instance, if one never heard any statistics about maternal mortality and learned that country X has a maternal mortality ratio of 76 per 100,000 live births, one could intuitively say that it is 76 women too many who died, but would not be able to say anything else significant. It wouldn’t be possible, for instance, to tell if 76 is a very high or very low number in relation to the country’s development level, or whether the country has made progress in reducing maternal mortality. Therefore, the basic tools proposed here compare an indicator with various types of reference points or objective benchmarks against which it can be judged.26 For the purposes of human rights monitoring, I suggest using one of the following types of benchmarks against which to compare human rights indicators:

(1) International human rights standards. For example, the obligation of universal primary education sets a benchmark of 100% primary education completion rate. Comparing rates in the focus country with the relevant international human rights obligation can reveal shortfalls in the enjoyment of a right in the focus country.

(2) A commitment taken either by a state or by a specific government. This can include a legal commitment enshrined in a state’s constitution or basic education law to spend a certain percentage of its government budget on education; the commitment assumed by a state when adopting the MDGs of reducing under-five mortality rate by two-thirds between 1990 and 2015; or a publicly-made commitment by the current president of a state to increase public housing by 20% in two years. Such comparisons would reveal the disparities of the relevant indicator in the focus country with the commitment taken by the state or the specific government. The commitment itself should also be scrutinized, as it could be flawed from a human rights perspective.

(3) A past value of an outcome indicator or a process indicator. In the case of an outcome indicator, these comparisons reveal if the state has made progress or has regressed in the level of ESC rights enjoyment. In the case of a process indicator, it reveals whether a state has made progress or has regressed in the proportion of people in the country who make use of a good or service deemed essential for enjoying a right.

(4) Countries with similar levels of development as the focus country.27 These cross-country comparisons could reveal whether the levels of deprivation of the focus country are lower than expected given the country’s development level. This could be related to an aspect of an ESC right (outcome indicator) or to the proportion of people who make use of some good or service deemed essential for enjoying a right (process indicator).

(5) Disaggregated national data (male/female, indigenous/non-indigenous, poor/non-poor, etc). This type of comparison could help identify disparities, and therefore possible discrimination, among population groups in the access to and enjoyment of economic and social rights.

The proposed approach consists of three basic steps: firstly using quantitative data to identify economic and social rights deprivations and disparities of outcome, from the perspective of core obligations, progressive realization and non-discrimination; secondly analyzing the main determinants of these outcomes so as to identify the policy responses that can reasonably be expected of the state; and thirdly using quantitative data combined with qualitative information, to assess to what extent deprivations, disparities and lack of progress can be traced back to failures of government policy.29

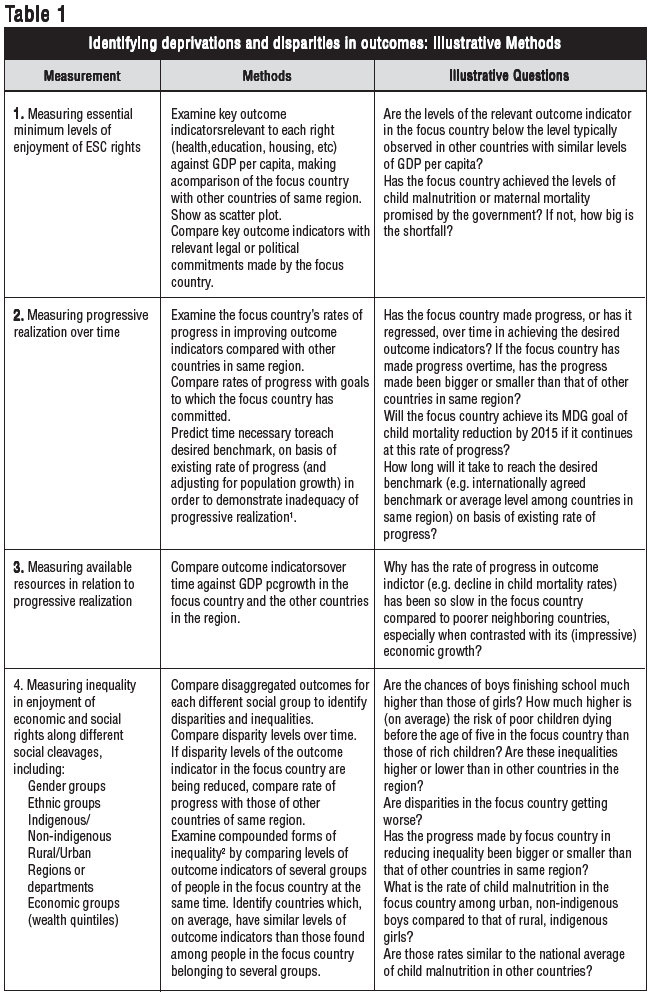

The first step of the proposed methodology uses outcome indicators, such as primary completion rates, maternal mortality rates or child malnutrition rates, to identify deprivations and disparities in the enjoyment of economic and social rights. The selection of relevant outcome indicators should be determined primarily based on the legal or normative standards of each right, but should also take into account data availability.

Examining outcome indicators not only provides a snapshot of the level of enjoyment of economic and social rights in a given country, but also helps evaluate whether states – the primary duty-holders of human rights – are complying with key aspects of their human rights obligations. Specifically, they can help assess whether a state is complying with its “minimum core obligations”, since theyreveal the extent to which the population is deprived of the most basic elements of the right to health, education, food and other economic and social rights. International comparisons provide a useful benchmark of what has been achieved in countries with similar resources.

This step also serves to measure progressive achievement according to maximum available resources since it enables one to measure human rights progress or retrogression over time according to the level of a country’s development. Furthermore, disaggregated data can reveal wide disparities in the enjoyment of economic and social rights by gender, ethnicity, socio-economic status or geographic location (e.g. urban/rural) which may be result from the discriminatory effects of government policy.

The following table provides an illustrative list of simple tools that use outcome indicators to monitor the various dimensions of state obligations pertaining to economic and social rights.

It should be stressed that evidence of deprivation or disparities in the enjoyment of ESC rights does not provide in and of itself conclusive evidence that a state has violated a right. This is because, as noted above, deprivations or disparities could be the result of factors beyond the control of a government. In some cases, a state may have made more effort to reduce deprivations or inequalities in education, health, food security than its neighbors, and yet because of circumstances beyond its control, the levels of deprivation or inequalities have worsened.32

Similarly, disparities in outcome indicators by gender or ethnicity are not in themselves proof of discrimination. In some cases, they might be the result of economic, historic or other factors and they might exist in spite of a government’s genuine efforts to close those enduring gaps. Nevertheless, evidence of deprivation or disparities may be suggestive of specific human rights violations and can serve as a crucial first step in a more comprehensive human rights assessment.

A second step is to identify the various causes of those deprivations and inequalities in the enjoyment of economic and social rights. Understanding the nature and extent of the obstacles preventing the enjoyment of economic and social rights is necessary to assess the adequacy of policy interventions undertaken by the state to address those obstacles. While the first step is more directly related to the realization of the right from the perspective of the right-holder, this step and the following one help to assess the extent to which the state, as the primary duty-bearer, is complying with its human rights obligations.

Many factors combine to affect the level of enjoyment of economic and social rights. In the case of health, the human rights framework explicitly acknowledges that the right to health extends not only to timely and appropriate health care, but also embraces a wide range of socio-economic factors that promote conditions in which people can lead a healthy life. This extends to the underlying determinants of health, such as food and nutrition, housing, access to safe and potable water and adequate sanitation, safe and healthy working conditions, and a healthy environment.34 Similar factors affect also other rights. For instance, socio-economic and cultural factors, as well as a range of underlying determinants related to other rights, affect the enjoyment of the right to education, the right to food, and the right to adequate housing.

A vast literature on the determinants of social outcomes has been produced over the years by economists, educational specialists, health experts and other social scientists. It is beyond the scope of this article to review this literature, but it is worth pointing out some basic distinctions found in the literature about the different types of factors that affect key areas of education, health or food security, leading to high levels of school drop-out rates, of maternal or child mortality, and of chronic malnutrition.

i. Supply-side and demand-side factors:35 Health and education determinants can be broadly classified as supply or demand factors. Supply-side factors are associated with the provision of health and educational services. They are directly related to government policies and interventions, and include government-provided inputs like clinics and schools, medical and school supplies and equipment, teachers and physicians, etc. Indicators of supply typically measure one of the elements defined by the, defined as the essential features or elements of a right, namely availability of goods and services, physical accessibility of services and facilities (e.g. distance to schools and clinics) andaffordability (economic accessibility) of services, adaptability or cultural acceptability of services (e.g. gender sensitivity and cultural adequacy of the services) and quality of services.36

At the same time, provision of goods and services are not sufficient to ensure the use of essential inputs necessary for the enjoyment of ESC rights. Services or goods may be available, but they may not be used often because of the demand-side factors that determine the utilization (or use) of health and educational services. Although their influence on health and educational outputs is more indirect than that of supply-side factors, demand factors are nonetheless critical elements of what may be “a long and complex causal pathway” leading to a given outcome.37

The two main determinants of service demand are poverty and cultural barriers. Income poverty may determine whether a household can afford to pay for medical services or send its children to school. The costs associated with going to school – including both the direct costs of attending school, such as uniforms, books, school supplies and transportation, and the indirect cost of sending children to school rather than to work – are often prohibitively high for the poor. These costs are the primary reason why children fail to enroll or end up abandoning school in many poor countries.

The effects of low income, however, go beyond limited ability to pay for healthcare and education. For example, it both increases exposure and reduces resistance to disease: poor people cannot afford clean water and sanitation, or non-polluting heating and cooking fuels, thereby increasing levels of exposure to unsanitary conditions. They are also likely to be malnourished, thereby reducing their resistance to sickness.38 At the same time, income poverty is typically associated with malnutrition and poor housing conditions, both of which generally inhibit the ability of children to learn.

Cultural beliefs or barriers can sometimes be strong determinants of who demands and uses health and educational services. This is particularly notable with culturally-defined roles between males and females. For instance, girls’ engagement in household chores and care economy (i.e. taking care of siblings, sick and the elder) adversely affect girls’ school participation. Similarly, concerns such as perceived unsafe school environment, son preference, lack of female teachers that can serve as role models, etc, are all factors that influence household decisions to send their girls to school. Cultural barriers may also prevent women from using health care services because health care providers are men, or because women have limited mobility. Similarly, son preference often implies that households do not invest in healthcare for girls and women.

ii. Direct and indirect determinants: Not all factors affecting these social outcomes (causing or exacerbating levels of deprivation or inequality in the rights enjoyment) do so directly. In fact, various authors talk about a long sequence of interlinked causes leading to a given output or outcome. Several conceptual frameworks have been developed to understand the relation between various determinants. Depending on the proximity of the effect they have on the outcome, we could distinguish between direct determinants (those determinants that directly affect a social outcome) andindirect determinants (those determinants that affect the outcome through their effect on a direct determinant or another indirect determinant).39

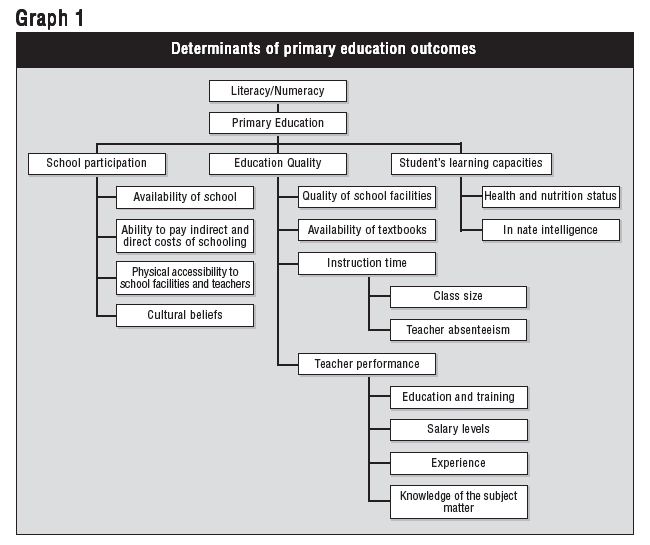

The following diagram illustrates these various types of determinants on one desired social outcome. if acquiring literacy and numeracy is a desired outcome of primary education – which certainly constitutes a key aspect of the enjoyment of the right to education – one could say, based on the literature on the determinants of primary education outcomes, that the direct determinants of this desired outcome, affecting each student differently depending on her or his circumstances, are school participation, education quality and student’s learning capacities.

In turn, each one of these immediate determinants is influenced by a set of indirect determinants.School participation depends not only on the availability and physical accessibility of students to school facilities and teachers, but also to demand factors, such as the ability of poor families to pay the direct and indirect cost of schooling, the cultural beliefs of households (such as bias of parents against investing in girls’ learning). Education quality depends on a whole set of factors, including the quality of school facilities,40 the availability of textbooks,41 instruction time and teacher’s performance. Students’ learning capacities depend, among other factors, on their health and nutrition status42 and student’s specific characteristics, such as innate intelligence.

Each of these indirect determinants or factors is in turn influenced by other indirect factors. Thus, instruction time is affected by class size, as well as by teacher’s absenteeism,43 and teacher performance is affected by their education and training, their salary levels, their experience, and their knowledge of the subject matter.

As reflected in this brief and incomplete account of determinants on primary education outcomes, navigating through the web of determinants that may affect a single outcome is a complex undertaking. In reality, things are even more complicated because the extent to which any factor has an impact may change from country to country, and different outcomes may have an impact on each other and on inputs. Moreover, the lack of significant progress in the reduction of deprivations is sometimes the result of a confluence of factors, only some of which can be attributed – in total or in part – to the state. For instance, in its 2005 World Health Report, the WHO pointed out that the lack of significant progress of many countries in maternal and child health was related to both contextual issues such as humanitarian crisis and the direct and indirect effects of HIV/AIDS, as well as to failures of health systems to provide good quality care and services to all mothers and children.44

Because of these and other complexities, a complex analysis of the causes of deprivation or disparities in any given country (why, for instance, country X has such a high incidence of children not completing primary school and the relative impact of each factor, or the extent to which different underlying factors can explain the wide disparities between various groups of the population in maternal mortality rates in country Y) generally entails a rather sophisticated use of technical knowledge and tools (such as complex statistical analysis) that most actors within the human rights movement working on ESC rights – whether advocates in national or international NGOs, members of a Treaty Body or Special Rapporteurs – are unequipped to carry out.45

But fortunately, for the purposes of human rights advocacy, there is no need to establish firm causal links between an outcome and a whole web of determinants, nor is there necessarily a need to estimate very accurately the exact impact of specific factors on certain outcomes. Advocates can instead rely largely on the myriad studies conducted by social scientists that have already identified the main reasons for existing deprivation and inequalities in areas such as nutrition, maternal mortality and schooling.

This step in the proposed methodology identifies and exposes cases in which specific actions or omissions of state policy contribute to the creation, perpetuation or exacerbation of high levels of deprivations or inequalities in the enjoyment of economic and social rights, as identified in Step #1. The tools proposed in this step could help identify cases in which the government had the capacity to deal with some of the determinants of specific deprivations and inequalities identified in Step #2, but failed to do so. Thus, this step is crucial for building the case that there has been a violation of economic and social rights.

The proposed tools focus on the main determinants of deprivations and inequalities: (A) supply-side factors and (B) demand-side factors. They also assess the state’s commitment to providing the adequate and equitable resources that are often needed to address these factors (C).

The adequacy of government goods and services affecting health and educational outcomes can be assessed with reference to the essential features of a right that, as mentioned above, the CESCR has defined for several ESC rights, namely availability, accessibility, quality and acceptability.

The following is a list of illustrative quantitative tools that could be used for this purpose.

The CESCR established that educational institutions and programs, as well as healthcare facilities, goods, services and the underlying determinants of health, must be available in sufficient quantity within a state. The goods and services essential for the realization of the right to education include, for instance, school buildings, sanitation facilities for both sexes, safe drinking water, trained teachers, teaching materials, etc. The underlying determinants of health necessary for the realization of the right to health include safe and potable drinking water, adequate sanitation facilities, hospitals and clinics, trained medical and professional personnel, and essential drugs.

With some of these goods and services, determining whether they are available “in sufficient quantity within a state” might be relatively easy, since “in sufficient quantity” would mean that person or household has them. That is the case, for instance, with services such as adequate sanitation facilities and potable water. But with many others services, such as the number of hospital beds per 1,000 people or the proportion of births attended by skilled health personnel, simply knowing the total number or the percentage of those services per X inhabitants may not be sufficient to assess whether they are “available in sufficient quantity within a state”. Two simple tools might be helpful for this purpose:

Internationally accepted benchmarks: One simple tool to use, when available, is an objective benchmark related to specific education or health services. This is typically based on empirical evidence about the effectiveness of the benchmark on a desired education or health outcome. Examples of these benchmarks include:

a) The “Education For All Fast Track Initiative”: a global partnership launched by the World Bank to help low-income countries meet the education MDGs has an indicative benchmark of one trained teacher for every 40 primary school-age children and another of between 850 and 1000 annual instructional hours for pupil.46

b) The guidelines developed by WHO, UNICEF and UNFPA to monitor the availability and use of obstetric services consider that for every 500,000 people, there should be at least four basic emergency care facilities and at least one comprehensive emergency facility.47

c) Joint Learning Initiative, an enterprise engaging more than 100 global health leaders in landscaping human resources for health suggest, based on empirical evidence, that a density of 2.5 workers per 1,000 may be considered a threshold of worker density necessary to attain adequate coverage of some essential health interventions and core MDG-related health services. These interventions and services can include 80 percent measles immunization coverage, and 80 percent births attended by skilled professionals.48

Cross-country comparisons: Comparing the levels of goods and services in the focus country with those of other countries in the same region. For instance, if the focus country has a much lower proportion of immunization rates, fewer hospital beds per 1,000 people, lower proportion of people with access to an improved water source, lower percentage of textbooks per pupil, or higher pupil-teacher ratio than most of the countries in the region, it would suggest that these levels are insufficient given its level of development, and that the focus country has failed to ensure the availability of these essential services in sufficient quantity. Similar to the cross-country comparisons of outcome indicators made in Step #1, cross-country comparisons over time can also useful for assessing whether the progress the focus country made has been bigger or smaller than that of other countries in same region.49

Quantitative tools can be used to assess inequalities in the accessibility of various sectors of a population to essential services needed for the enjoyment of economic and social rights.

The simplest method is to examine whether any underprivileged or marginalized societal group, such as women, ethnic minorities, indigenous peoples, rural residents or poor people, has less access to an essential service or good than their relevant counterpart (i.e. men, ethnic majority, non-indigenous peoples, urban residents or rich/non-poor people). For instance, a study of the determinants of parasitic infections in school-age children in Western Ivory Coast showed that schoolchildren from poorer households lived significantly further away from healthcare facilities compared to schoolchildren from richer households50 and another study has shown that the inequality in immunization coverage between rich and poor children in India is higher than for any other Asian country for which there is data available.51

Quantitative indicators could also be helpful for measuring the quality of services provided. For instance, data about conditions of health clinics or school facilities could reveal that a country has a high proportion of health clinics or school facilities in poor conditions (e.g. with leaking roofs, without proper sanitation or access to potable water, etc). Reviewing standardized tests for teachers, one could learn about some key aspects of teacher qualifications, a primary determinant of the quality of education. Similarly, one could review assessments of health professionals.

Disparities in the quality of the services provided can also be identified using quantitative tools. Although there might not always be data available explicitly showing that vulnerable or marginalized sections of the population receive poorer quality services than other segments of the population, it is often possible to reach this conclusion by comparing disaggregated data by region or municipality about the quality of an essential service (e.g. quality of teachers or health professionals, conditions of school facilities or clinics, etc.) with population data about the same regions or municipalities disaggregated by ethnic groups or poverty levels. This could show, for instance, that the conditions of health clinics in the areas mostly populated by an ethnic minority or by poor people are worse than those enjoyed by the ethnic majority group or the non-poor.

As discussed above, the reasons for avoidable deprivations and for inequalities in the enjoyment of ESC rights are often also related to demand factors, such as the cost of schooling and health care. Therefore, monitoring of state policy efforts must go beyond monitoring the adequacy of the supply factors to analyze the extent to which a state has adequate policies and programs addressing the demand factors possibly preventing people from using the good and services necessary for enjoying economic and social rights.

Addressing demand-factor problems can be undertaken by adopting various types of policy interventions or programs, often implemented by different agencies of a government. For instance, when the costs of education and health prevent poor people from utilizing essential education and health services, the state could address this problem through a type of direct policy intervention (e.g. subsidizing the costs of education for the poor through scholarships, or providing school meals as a means to tackle child malnutrition) or through an indirect policy intervention (e.g. adopting macroeconomic policies aimed at reducing poverty).

Direct policy interventions to tackle demand-side obstacles to the enjoyment of economic and social rights are specifically aimed at removing a particular demand-side obstacle. This type of interventions are usually carried out through focused programs by the government agency that has overall responsibility for the relevant sector (i.e. the Ministry of Education to tackle a demand-side obstacle to the right to education or the Ministry of Health to tackle a demand-side obstacle to the right to health).

Empirical evidence shows that direct interventions addressing demand-side problems are often effective when adequately funded and well-targeted to those most in need. For instance, programs meant to mitigate the effects of poverty on educational outcomes, such as providing scholarships or free textbooks to disadvantaged children, or offering school meals to encourage children to attend or remain in school, have proven to be effective in many countries in offsetting the direct costs (uniforms, exercise books, textbooks, transport, etc.) and indirect costs (the opportunity cost to households of sending their children to school rather than out to work) of education.52

Following are some initial suggestions of quantitative tools that can be helpful to assess whether the manner in which the focus country has implemented such programs has been adequate in key aspects such as coverage, funding and distribution of benefits.

Identifying inadequate coverage: It is simple to assess the sufficient coverage of a program aimed at addressing a demand-side obstacle to the enjoyment of economic and social rights: compare the number of people covered by the program with the number of people affected by that specific demand-side obstacle. For instance, if a scholarship program meant to offset the costs of education is reaching only 10% of the poor families not sending their children to school because of those costs, then the program coverage is patently insufficient.

Identifying underfunded programs: An international comparison can show whether the focus country is spending sufficient resources in a program aimed at addressing a demand-side obstacle. This is done by a double comparison of the resources a country devotes to a specific program with those spent on similar programs in other comparable countries of the same region, related to levels of the relevant deprivation in these countries that these programs are supposed to address.53

Measuring whether program benefits are unfairly distributed: Analyzing distribution of the benefits of a program aimed at boosting demand by group (e.g. indigenous/non-indigenous, poor/non-poor) or location (e.g. provinces or municipalities) and contrasting them with levels of deprivation that program is supposed to address across the same groups or locations, can help identify unfair distribution patterns that benefit people who do not need these programs the most.54

Indirect policy interventions are aimed at changing the socio-economic or cultural factors that gave rise to the demand-side factor to begin with. Unlike direct policy interventions that are typically very focused on a specific program carried out by the government agency that has overall responsibility for the relevant sector, indirect policy interventions, which are meant to address broader socio-economic or cultural factors, often require a whole set of programs carried out by a whole set of government agencies. For instance, a comprehensive strategy for poverty reduction requires a multi-sectored approach in order to undertake a whole set of macroeconomic, structural and social policies and programs.

Determining which indirect policy interventions to examine when monitoring state’s efforts to comply with their economic and social rights obligations largely depends on which factors are preventing people from realizing their rights in a specific circumstance

Imagine for instance that during Step #1 of the proposed methodological framework, one finds that in the focus country, a large proportion of girls are dropping out of school, while most boys complete primary school. If in Step #2, one finds that customs and social norms may be influencing parents’ decisions not to send girls to school, then in Step #3, one should see whether the government has made efforts to counteract these entrenched social norms that have proven to be useful in other circumstances. This could include legislative reforms such as marriage rights and inheritance,55 or public awareness campaigns about the benefits of girls’ education. But in Step #2, one may find that the primary reason that many parents are not sending their girls to school is not due to cultural or social norms, but rather due to economic reasons. For example, in that country, educated boys can expect to receive more future income than equally educated girls, and poor households without the means to send all their children to school, thus choose to send boys rather than girls. In such a case, during this step, one should assess whether governments have made specific efforts to change labor market circumstances, so that it does not discriminate against women, and so that opportunities and advantages faced by all children at given levels of education and achievement are broadly equal.56

The appropriate measures which a state should take as part of its policy efforts include legislative, administrative and financial measures.57 A key area of policy effort success is the degree to which sufficient resources are allocated to social sectors, such as the educational or health system, and whether this allocation is distributed in line with need.

An in-depth budget analysis is optimal for this purpose. Some pioneer NGOs have made important inroads in this regard, integrating rigorous budget analysis into a human rights framework.58 But many human rights activists may not have the technical skills, time or resources required to undertake complex budget analysis. It is nevertheless possible to adopt simple quantitative tools helpful in assessing the adequacy and distribution equity of resources devoted to the realization of economic and social rights.

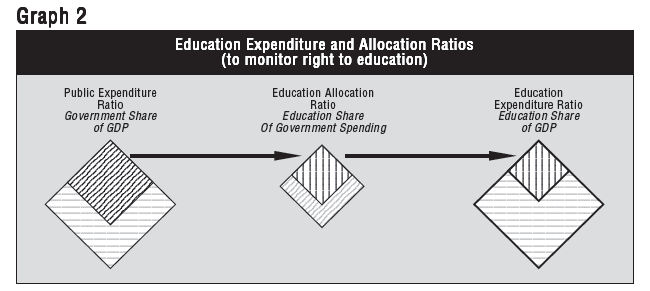

A basic framework of expenditure and resource allocation ratios can be used to conduct a basic analysis of expenditure patterns. This framework is adapted from a set of four ratios proposed by UNDP to analyze public spending on human development.59 UNDP suggests that these ratios are “a powerful operational tool that allows policy makers who want to restructure their budgets to see existing imbalances and the available options”.60 But these ratios could also be a powerful monitoring tool allowing human rights advocates to identify when:

• a government devotes insufficient resources to an area related to a specific right, such as education, health, food security, etc;

• a government appears not to raise sufficient revenues to be able to adequately fund the competing needs the state has.

• Within a sector related to ESC rights, a government allocates disproportionately little resources to those budgetary items that should be a priority, in that they could have more impact on ensuring minimum essential levels of rights enjoyment in areas related to core elements of the right to health, education etc (e.g. disproportionate spending on tertiary versus primary education, or on metropolitan hospitals as opposed to rural primary health care services

1. Expenditure ratios refer to the percentage of GDP spent on public, social or education/health expenditure. Examples:

Public expenditure as % of GDP = public expenditure ratio

Social expenditure as % of GDP = social expenditure ratio

Education expenditure as % of GDP = education expenditure ratio

Health expenditure as % of GDP = health expenditure ratio

2. Allocation ratios refer to % of public expenditure allocated to social, education, health etc spending. Examples:

Social expenditure as allocated share of public expenditure = social allocation ratio

Education expenditure as allocated share of public expenditure = education allocation ratio

Health expenditure as allocated share of public expenditure = health allocation ratio

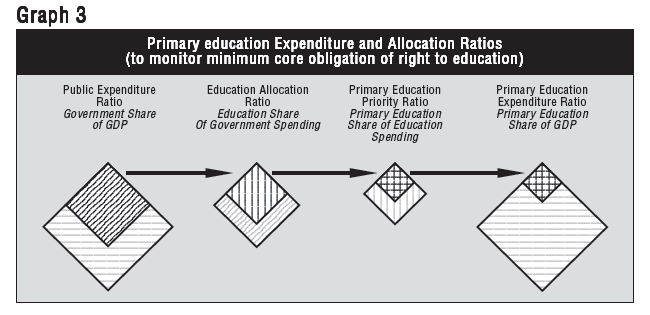

3. Core obligation priority ratios refer to the share of spending on education, health or other social sector that is assigned to minimum core obligations, such as primary education or maternal health care. Examples:

Primary education spending as share of education expenditure = primary education priority ratio

Maternal health as share of health expenditure = maternal health priority ratio

4. Core obligation expenditure ratios refer to spending on these areas of core obligation as a % of GDP. Examples:

Primary education spending as share of GDP = primary education expenditure ratio

Maternal health spending as share of GDP = maternal health expenditure ratio

The right to education could be used to explain the usefulness of this set of ratios.

This ratio determines the size of a government’s budget in relation to the size of its economy (using GDP as a proxy). It indicates the “size of the cake” of resources a government has at its disposal to undertake all its functions. Since taxation is generally a major funding source for public expenditure, this ratio often depends largely on investing in taxation levels Although possibilities for raising taxes may partially depend on state capabilities,61 they also depend in varying degrees on state policy decisions.

If this ratio is too high, this might cause problems for economic growth, which in turn could jeopardize the sustainability of economic and social rights realization.62

If this ratio is too low, it would make the state too weak and unable to adequately provide resources for the many competing and often essential functions of a state. A persistently low ratio can reflect a state structural problem – for instance, state capture by an economic elite resisting any substantial tax increases or strengthening of the state –63 that could seriously impair the state’s ability to realize its economic and social rights obligations.

This is the most basic expenditure ratio related to the right to education. It provides a snapshot of the extent of state commitment to the provision of education, reflecting the level of resources a state is willing to invest in its realization. If there were only one ratio to monitor government expenditure related to the right to education, it would probably be this one.

A low education expenditure ratio would mean that resources may be insufficient for the educational system as a whole to effectively address the various obstacles, both supply and demand factors, that may be inhibiting children’s access to quality education. Moreover, when this ratio is very low, it could seriously undermine any state effort or program to improve the availability, affordability or quality of the educational system, and could severely diminish the effectiveness of any program adopted to address the demand-factors related to school desertion.

This ratio reflects the relative priority given to education among competing budgetary needs.

The extent to which a low education allocation ratio is problematic from a human rights perspective depends on the circumstances. The level of enjoyment of a specific right is crucial. A state that has fulfilled its minimum core obligations regarding the right to education (meaning that most of the population is literate and practically all children enjoy access to primary education) might be justified in reducing its education spending to reallocate it to another social sector in which there might still be a significant proportion of people deprived of essential levels of health care or shelter, for example. Even if these other sectors are not worse off than the education sector, it could still be legitimate for a state to invest relatively more on housing than on education, or more on education than health. According to international law, national sovereignty implies that governments have a large margin of discretion in selecting the appropriate measures necessary for realizing economic, social and cultural rights. This of course includes spending priorities.64

But if there is a high level of illiteracy or yawning disparities in the primary completion rates of boys and girls in the state, a low education allocation ratio would not be justified. It would also be necessary to search for any type of extravagant spending that squanders state resources on unnecessary areas.65

This ratio reflects priorities within the educational system. Interpreting low levels of this ratio depends once again on the circumstances. In countries where a significant proportion of the population is illiterate or many children are deprived of the most basic forms of education, a low primary education priority ratio could be interpreted as a violation of a state’s minimum core obligations regarding the right to education. As Philip Alston points out, in a country with very limited resources the maxim that “poverty is a denial of human rights” would be often valid in legal terms if the government “has failed to take possible steps to improve the situation and instead has opted to devote scarce resources to other objectives that do not address directly the realization of basic rights”.66 This is precisely what is happening in many poor countries, where the most impoverished people lack primary health care and basic education, but the state allocates most of its social spending on the non-poor.

This regressive pattern of spending may also be considered a covert form of discrimination, where, for example, investments “disproportionately favour expensive curative health services which are often accessible only to a small, privileged fraction of the population, rather than primary and preventive health care benefiting a far larger part of the population”.67 On the other hand, countries that have already achieved high standards of primary education may be well justified in prioritizing higher education levels.

This ratio reflects the level of resources a state is willing to invest in its minimum core obligation to ensure the satisfaction of the most basic form of education, out of the “maximum of its available resources”, using GDP as a proxy). It is the result of three key policy decisions: 1) the size of the government’s budget (the public expenditure ratio) 2) Educational sector allocation (Education Allocation ratio) 3) Primary education allocation (Primary Education Priority ratio).

Choosing which ratio or combination or ratios to use in the monitoring process depends on a set of factors:

• The focus of the monitoring: Is it the whole gamut of economic and social rights, only one right, or one specific aspect of a right (such as primary education or maternal mortality)?

• The scope and purpose of the monitoring exercise: Is it in-depth research on a specific right, a shadow report, or is it carried out by a Treaty Body?

• The type of obligation being monitored: Minimum core obligations, the duty of progressive realization according to available resources, or the obligation to ensure no discrimination in the enjoyment of rights?

• The availability of data.

i. How to Use the Ratios

There is no universal prescription for using each of these ratios, and they depend largely on the circumstances. But there is a basic method for determining if ratio levels in a given country are relative high or low.

Once again, this approach compares the ratio level with a reference point or objective benchmark against which it can be judged. Specifically, the insufficiency of key budget items for the realization of economic and social rights can often be identified with simple tools, by comparing them with:

(a) State commitment, such as the constitution, national plans, or political agreements. For instance, in its 1996 Guatemala Peace Agreements, the government committed itself “to step up public spending on education as a proportion of gross domestic product by at least 50 per cent over its 1995 level”.68

(b) The level of the same ratio of other countries in the same region.69

(c) A suggested benchmark based on empirical evidence. For instance, when originally suggesting these ratios as a means to analyze public spending from a human development perspective, UNDP provided certain benchmarks or guidelines about what the levels of these three ratios should be, namely: 25% for the public expenditure ratio, 40% for the social allocation ratio, and 50% for the social priority ratio,70 leading to a human expenditure ratio of 5%.71 Similarly, the WHO has set a global minimum target of 5 percent of Gross National Product (GNP) for health expenditure.72

The proposed quantitative tools are subject to a number of important challenges and limitations which need to be recognized and addressed if these tools are to be useful for monitoring a wide variety of countries.

The first challenge is that these simple tools work best in extreme cases, where the outcome deprivations and disparities are much bigger than those in neighboring countries, while the resources allocated to the health and education sectors are much lower. These tools may be less useful in their conclusions about countries not doing exceptionally badly. For such middle-ranking countries, simple tools may still be helpful in flagging possible concerns which arise when development statistics are analyzed in light of international human rights standards, but not for providing conclusive evidence of a country’s compliance with these obligations.73 In order to reach the more nuanced judgments required in such cases, more sophisticated tools are needed. Tools commonly used in the development field to measure equality-related issues (such as benefit incidence analysis used to evaluate equity of public expenditure)74 can be particularly relevant for countries performing reasonable well at the aggregate level, but still suffering from serious inequalities in the enjoyment of ESC rights among various groups in its population.

The second challenge of the proposed methodology is that, as with any quantitative tools, its applicability hinges on data availability, which varies significantly by country. This problem is particularly acute for disaggregated data by gender, ethnicity, socio-economic status and geography, such as rural and urban areas. Scarcity of data is obviously a problem not only for this particular methodological framework, but for almost any monitoring effort. This is why human rights Treaty Bodies frequently call upon State Parties to produce more data, without which, any monitoring exercise is severely weakened.

Although there is a serious problem of data availability to make a proper assessment of a government’s compliance with its ESC rights obligations in many countries, the human rights movement has not yet made use of all already available relevant data. An example the reports on ESC rights on specific countries that typically do not use and analyze household surveys, which usually contain a wealth of relevant data for human rights analysis.

Clearly, the analysis of household surveys or the use of more sophisticated quantitative methods than the simple ones proposed here – possibly necessary for conclusions on countries that are not extreme cases of underperformance –requires considerable training. But efforts in this regard by the human rights community may be worth it: as shown in recent years with some successful cases of using budget analysis for monitoring ESC rights, the ability of human rights activists to be able to use such tools for monitoring ESC rights could significantly strengthen the collective ability to make governments (and eventually other powerful actors) accountable for human rights violations.

Combining the strengths of traditional human rights advocacy methodologies with those of a socio-economic analysis used by economists and other social scientists could contribute to transforming the ability of the human rights movement to hold governments accountable for violations of economic and social rights.

Once tested and refined, a framework methodology for using quantitative tools, along the lines suggested above, could be potentially used more extensively by a whole range of actors within the human rights movement. For example, national and international NGOs could adopt it for monitoring and advocacy on a range of issues; monitoring treaty bodies and Special Rapporteurs could use it to promote more substantive dialogue with countries that claim not to have enough resources to address an issue;75 and public interest legal advocates could make use of more data in national and regional courts to enforce economic and social rights.

One of the strengths of this multidisciplinary approach to monitoring economic and social rights, is its versatility, which enables it to be further developed and adapted to different types of issues of various levels of complexity. The next challenge would be to set out tools for a human rights analysis of additional relevant indicators relevant to other ESC rights (such as the right to food, the right to housing or the right to decent work), adding to those for which the methodology toolbox was initially developed (the right to health, the right to education, etc). Then it would be useful to explore how this monitoring toolbox can be used to monitor ESC rights violations in developed countries, helping to critically address complex issues such as the health system in the United States, or the effects of social policies of countries in the European Union on the enjoyment of economic and social rights of the Roma people or the immigrant population from a human rights perspective.

Those with expertise in assessing the human rights impact of international economic relations could further develop such methodologies to address the impact of external actors, such as international financial institutions and industrialized nations in the global North, on the realization of ESC rights in developing countries. Topics may include agricultural subsidies, foreign debt or the effects of intellectual property laws on access to medicine. Combining rigorous economic research with human rights analysis, this multi-disciplinary approach would be useful to explore the human rights implications of trade agreements, to analyze the impact on worker’s rights of unregulated financial flows in a globalized economy, and to explore how structural adjustment programs have led to drastic cuts in social spending, impeding the ability of the state to provide basic needs such as health care and education.

To gradually being able to analyze such complex issues with rigour – critical for any effective advocacy – will required a concerted effort from people from various disciplines. No one discipline has the expertise or holistic perspective required to implement this approach alone. It requires interdisciplinary collaboration, to which there is often little more than a rhetorical commitment in the area of ESC rights advocacy. But the potential of theses efforts for being able to show the value-added of a ‘rights-based approach’ to development issues could be immense.

Quantitative tools are not a panacea for monitoring economic and social rights. When people are not treated by doctors because they belong to an ethnic minority, women are not informed of their reproductive rights or a whole village is forcibly evicted without any due process, the traditional monitoring methods that have served us so well in the human rights movement – of fact-finding investigations based on testimony gathering and legal research – may be more effective building a case of a violation than analyzing outcome and process indicators.

But quantitative tools are indispensable to assess the impact of broad public policies on the realization of ESC rights. When used strategically – and combined with qualitative research –quantitative tools can be particularly crucial to make governments accountable for the failure to prevent or rectify avoidable deprivations and inequalities in the enjoyment of economic and social rights. They can help us as human rights advocates not only to persuasively show the scope and magnitude of various forms of rights denial, but also in revealing and challenging policy failures that contribute to the perpetuation of those deprivations and inequalities.

Equipped with this type of tools, we can expand the range of issues that we can address as human rights advocates, and the areas of government policy that we can submit to human rights scrutiny and accountability. In particular, quantitative tools are crucial for monitoring the impact of public policies related to resource allocation and distribution on the enjoyment and realization of economic and social rights.

At the same, by interpreting the data obtained by these methods through a human rights lens that focuses on accountability, we furnish new meaning to these methods. They become powerful tools to expose multiple manifestations of social injustice. Thus, by exposing arbitrary cutbacks in social services or discriminatory policies depriving wide sectors of the population access to basic goods, this methodology can help identify, expose and challenge problems related to poverty that are usually perceived as irredeemably structural and therefore unsolvable –to causes that can be assigned to the actions (or inactions) of state agencies.

In 2005, Michael Ignatieff and Kate Desormeau noted that a measurement revolution has been underway in the fields of development and governance. By measurement revolution, they meant the exponential diffusion and rising influence of standardized and quantifiable measures of performance in international public policy. Yet, they noted that as this quantitative revolution has spread— increasingly measuring all aspects of human wellbeing, changing the way the way international organizations monitor governments’ behavior, and the way governments assess each other and target their aid and development policies—the human rights movement has stood aside.76

The pitiful failure of many governments to make significant strides in eradicating abysmal levels of inequality and deprivation, demands renewed efforts to demonstrate when and how these phenomena can be traced back to specific actions or omissions of state policy, and how they can be categorized as violations of internationally recognized human rights obligations.

Sixty years on from the Universal Declaration, it is time we joined the revolution and opened new fronts of struggle in the battle against economic and social injustice.

The examples below illustrate how some of the tools set forth above can be useful to assess compliance with human rights obligations in concrete situations. They all focus on the right to education in Guatemala and are based on an in-depth research project on Guatemala that the Center for Economic and Social Rights is currently undertaking together with the Central American Institute for Fiscal Studies.77 Tracing the link between Guatemala’s dismal human development outcomes and the deficiencies in public policy over the last decade, the study makes the case that the widespread deprivation and flagrant disparities in access to health and education are to a large extent avoidable, evidence of a clear lack of political will to realize the right to health and education of all sectors of the population.

By bringing to bear a range of quantitative and qualitative tools of socio-economic analysis to the assessment of compliance with human rights obligations, the approach adopted in this project seeks to operationalize the human rights framework so as to increase its usefulness as an instrument for enhancing public policy accountability and design.78

Guatemala has some of the worst education outcomes in Latin America. This becomes apparent when using some of the tools described in the previous section.

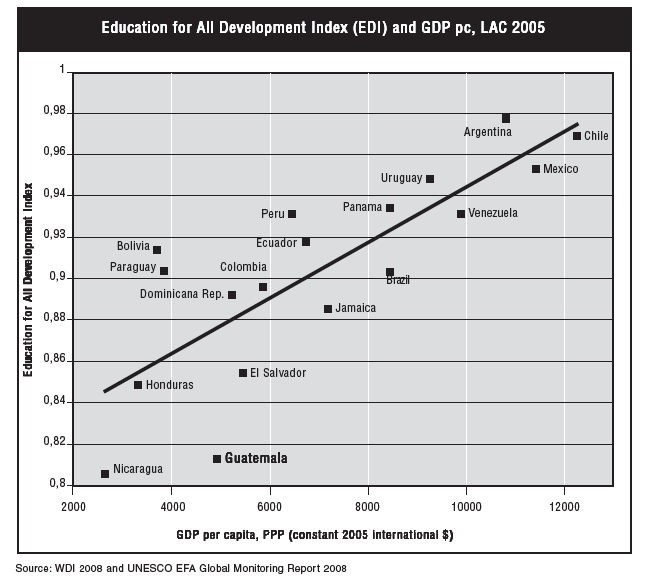

The following graph compares the Education for All Development Index, a composite indicator developed by UNESCO to capture the status of education in a given country.79

This comparison reveals not only that Guatemala has one of the highest levels of educational deprivations in the region, but that these deprivations are also significantly higher than Bolivia, Honduras or Paraguay, countries with lower levels of economic development. This suggests –it is not possible to reach a conclusion from only this fact – that Guatemala may be violating its obligation to the progressive realization of the right to education according to maximum available resources.

Disaggregated data makes it possible to identify inequalities in the enjoyment of economic and social rights among various groups in a population. For instance, the 2004 Guatemalan National Survey of Employment and Income found that children from the wealthiest 20% of society are more than twice as likely to finish primary school as the poorest 20% of children and that only 42% of rural children are likely to finish primary school, almost half the rate of urban children.80

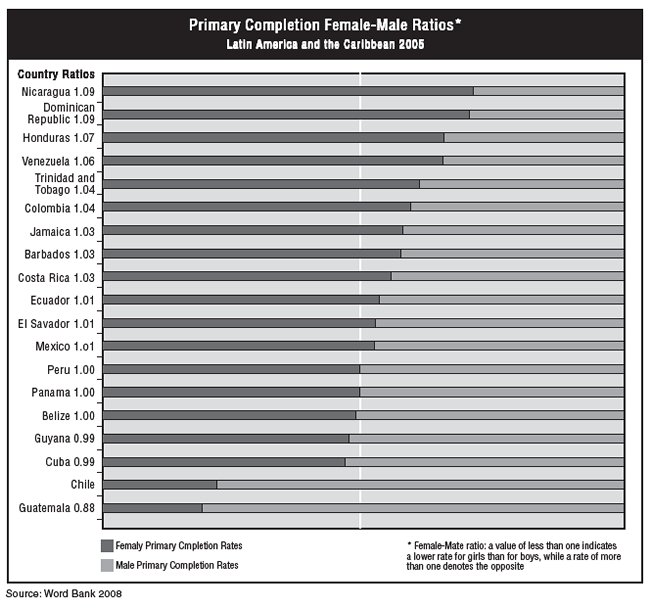

The next step is to evaluate if the inequality levels in one country are similar, better or worse than the inequality levels in other neighboring countries. The following graph shows that unlike most countries in Latin America, where a smaller proportion of boys than girls finish primary, Guatemala is one of the few countries in the region where fewer girls than boys finish primary school. Moreover, as the graph indicates, the disadvantage of girls is more marked for Guatemala than for any other country in the region.

Guatemala’s poor educational outcomes are largely the result of persistent state neglect. Consecutive governments have failed to remove the main obstacles that keep hundreds of thousands of children from obtaining a primary education, let alone good quality primary education. This failure is a violation of their right to education.

Presenting the full evidence for this conclusion is beyond the scope of this article81 . Nevertheless, simple quantitative methods, either alone or combined with qualitative research, can be used to assess the adequacy of Guatemalan policy efforts in addressing some of the main obstacles preventing so many children from enjoying their basic right to primary education. It should be stressed that each tool alone is not sufficient to reach a general conclusion, but their combination provides a compelling picture of the inadequate, insufficient and inequitable nature of consecutive governments’ response to those obstacles.

The main causes of so many Guatemalan children not finishing primary school are not supply-side factors such as shortage of schools or teachers, but rather demand-side factors related to the direct and indirect costs of schooling, which most poor families cannot afford to pay. The tools presented here are used to assess the adequacy of programs meant to address these demand-side factors. These are followed by some graphs illustrating tools used to measure key aspects in the quality of education, the main supply-side problem of the educational system in the country.

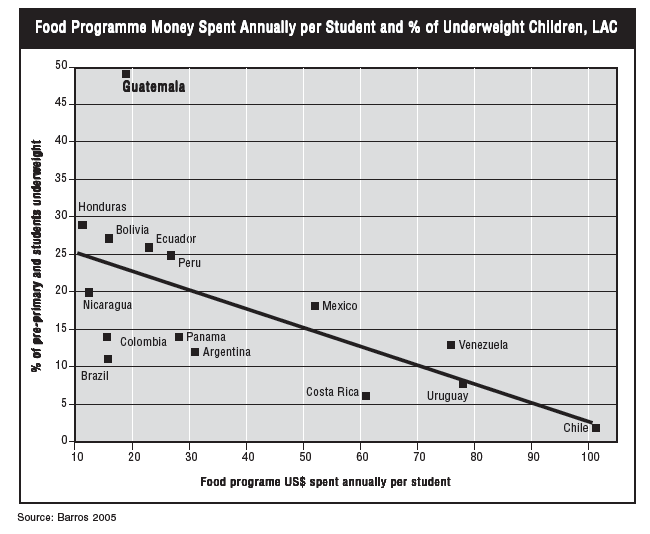

The next graph shows how much money per student Guatemala devotes to its existing school meals program (a program with the stated goals of reducing child malnutrition),82 compared with similar programs in other countries in the region. These figures are then contrasted with the magnitude of the problems that the programs purportedly attempt to overcome. The comparisons suggest that Guatemala’s financial commitment to this program is altogether incommensurate with the enormity of the deprivations.

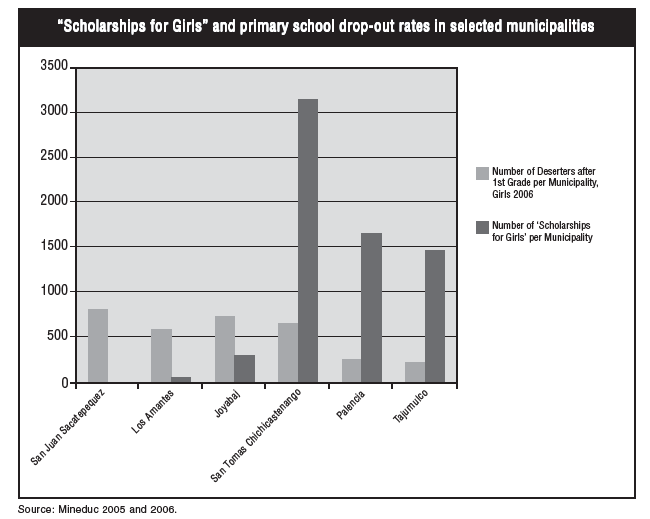

The following graph shows that the allocation of resources of Guatemala’s “Scholarships for Girls”, established to reduce the staggering repetition and desertion rates of first grade girls, has often been skewed. Some of the municipalities with a relatively low number of girls dropping out of school after first grade in 2005 received a large number of “Scholarships for girls” the following year. Other municipalities, with a much higher levels of girl deserters after first grade, received fewer scholarships the following year.

The first national systematic evaluation of primary teachers in Guatemala, carried out in 2004, revealed some key aspect of their qualifications: the average teacher performance in Spanish reading was low (58 out of 100) and very low in math (26 out of 100). These dismal results suggest that many teachers in Guatemala may not only be incapable of properly teaching these subjects, but that many teachers also do not have the basic reading skills necessary to fully benefit from government investments in service training or professionalization.83

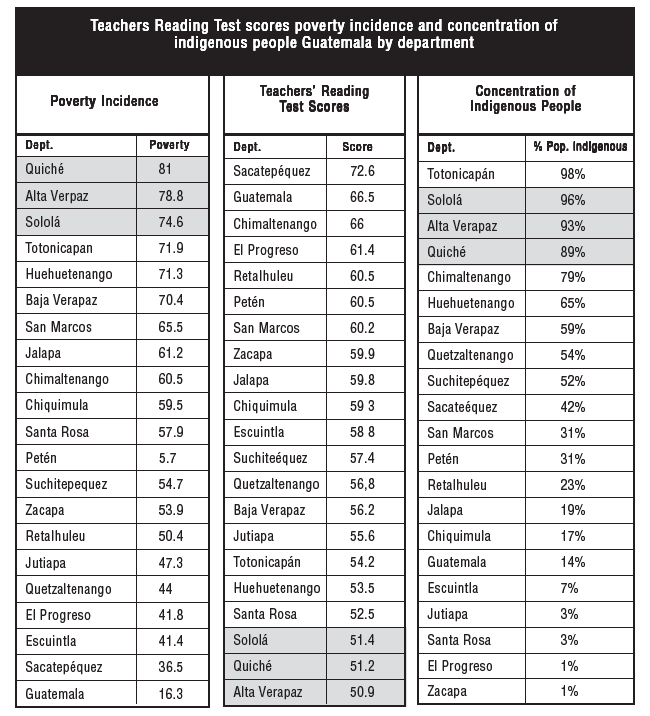

Comparing data from various data sets can reveal important information about violations of economic and social rights. The following graph shows that comparing results of the Guatemalan teacher evaluation by department84 with the incidence of poverty and concentration of indigenous peoples in each department reveals that the most disadvantaged children are being taught by the least qualified teachers. The three departments in which teachers had the lowest reading test scores are the three departments with the highest incidence of poverty. They are also among those departments with the largest concentration of indigenous people.

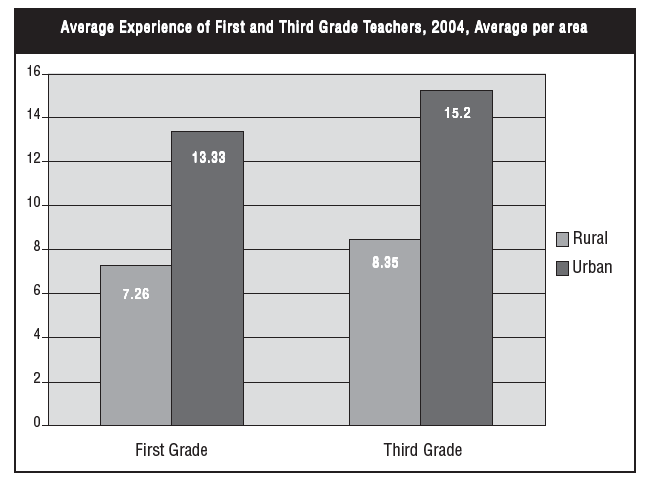

The inequity of the Guatemalan educational system can also be assessed by comparing the varying degrees of teachers’ experience by region. A comparison of primary school teachers’ average experience in urban areas with that of teachers in rural areas shows that urban teachers have, on average, nearly twice as much experience as rural teachers. Since empirical evidence in Guatemala shows that teachers with more experience have more capacity to provide a better quality education,85 a comparison of the average experience of teachers serving various sectors of the population helps assess one aspect of inequality in the quality of education.

This disparity contributes to the inequality of opportunity for Guatemalan children. Quality education is largely unavailable to poor and indigenous children, both groups who generally live in rural areas, as there is little opportunity for being taught by the most experienced teachers.

Combining these data on the disparities in teachers’ experience with cross-country comparative qualitative information suggests that urban-rural disparities are the result of Guatemala’s policy decisions. Other countries in the region, such as El Salvador, Honduras and Nicaragua, have introduced salary incentives to encourage qualified teachers to work in rural or disadvantaged areas.86 At the time of writing, Guatemala had yet to adopt any system of incentives that could secure the most capable teachers for rural areas.

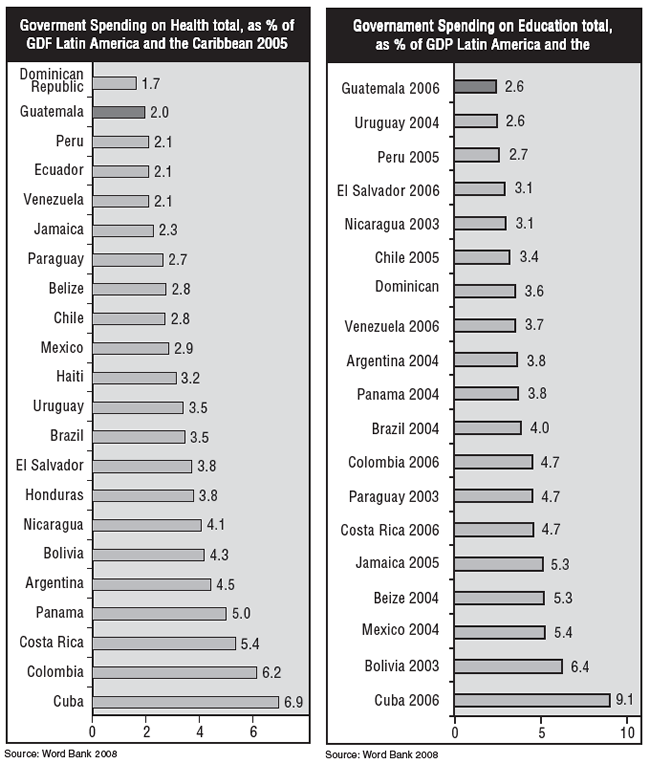

The following ccomparison of the level of government spending on education and health in Guatemala with those of other countries in Latin America, reveals that Guatemala has among the lowest levels of health and education spending relative to GDP in Latin America and the Caribbean.

1. I would like to thank my colleagues at the Center for Economic and Social Rights for their valuable feedback on earlier versions of this article, and, in particular Shira Stanton for the language editing and the graphs, Maria Jose Parada for her editorial suggestions and Ignacio Saiz for countless helpful conversations and for his invaluable editorial input. This article does not necessarily reflect the views of the Center for Economic and Social Rights.