An Analysis of the Jurisprudential Swings of the Supreme Court

This study aims to analyze the lack of effective compliance in Argentina with the decisions of the Inter-American Human Rights System (IAHRS). Through a case analysis, it evaluates the Supreme Court’s role in applying international law in general, and the decisions of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in particular. Based on this analysis, advances and setbacks are identified in the different positions adopted by the Supreme Court, which then allows for the identification of problems. Finally, the study proposes a way by which to overcome the challenges and thereby improve the level of compliance with IAHRS decisions.

The effectiveness of the Inter-American Human Rights System (IAHRS) is a topic that attracts increasing attention, given concerns about a lack of compliance with its decisions by different bodies. In particular, one could highlight the publication in 2010 of two quantitative studies that examined the degree to which the decisions adopted by the bodies of the IAHRS were effectively applied (BASCH et al., 2010; GONZÁLEZ-SALZBERG, 2010).

The two publications are far from identical; for one thing, they each analyzed different sets of data. While the analysis done by the Association for Civil Rights (ADC) included decisions from both the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IAHRS Court), our work focused solely on the decisions issued by the Court. Likewise, the ADC study was limited to evaluating the decisions taken within a five year period, whereas our study looked at all sentences issued by the Court since it began in 1987 until the end of 2006 – decisions the Court would have monitored for compliance as of late 2008. Similarly, another important difference is in the conflicting conclusions drawn about the effectiveness of the IAHRS; this can be attributed to differences in indicators, rather than substantial differences in data measurement.

On the other hand, the studies agree on the urgent need to improve compliance with IAHRS decisions. However, our analysis exposed strong reasons to believe that the measures necessary to achieve this objective should come from within States themselves, and here we diverge from some of the proposals in the ADC study.

Meanwhile, the ADC’s point on the importance of focusing on strengthening national implementation mechanisms could be very wise. In particular, attention should be placed on the need for States to recognize that compliance with IACHR Court decisions is mandatory. Above all, the judicial powers of the States must accept the binding nature of the decisions of the judicial body of the IAHRS, given that – as will be explained shortly – this is where the greatest obstacles to effective compliance can be found. We therefore believe that this is the necessary starting point for any analysis of compliance with IAHRS decisions within national contexts.

Against this backdrop we present our work, limiting ourselves to the case of Argentina in order to analyze the role played by the country’s highest court regarding recognition of the binding nature of the IACHR Court’s decisions. First, we describe the present situation with respect to Argentina’s compliance with IACHR Court decisions, exposing current problems. Next, we analyze the evolutionary development of the implementation of international law in the jurisprudence of the Supreme Court of Justice of Argentina (CSJN), in general terms, in order to understand the origins of the current situation. Special attention will be given to the last constitutional reform, because it generated a paradigmatic shift with regard to how IAHRS decisions were treated in the courts. Finally, we evaluate how the CSJN has treated the decisions of the IAHRS and in particular the decisions of the IACHR Court. The goal will be to identify both the shortcomings and the strengths of the CSJN in order to determine how best to improve compliance with IAHRS decisions.

As of 2010, the Argentine State had been convicted by the IACHR Court six times (CORTE INTERAMERICANA DE DERECHOS HUMANOS, Caso Garrido y Baigorria v. Argentina, 1996; Caso Cantos v. Argentina, 2002; Caso Bulacio v. Argentina, 2003; Caso Bueno Alves v. Argentina, 2007a; Caso Kimel v. Argentina, 2008a; Caso Bayarri v. Argentina, 2008b). In addition, the State had not fully carried out all of the reparations ordered in any of the verdicts. That does not mean that the State has ignored these decisions; according to the monitoring done by the IACHR Court itself, the State has adopted measures aimed at complying with all of these decisions, with the exception of the “Buenos Alves” verdict (CORTE INTERAMERICANA DE DERECHOS HUMANOS, Caso Buenos Alves v. Argentina,2007a), which the IACHR Court had not yet commented on as of mid 2011.

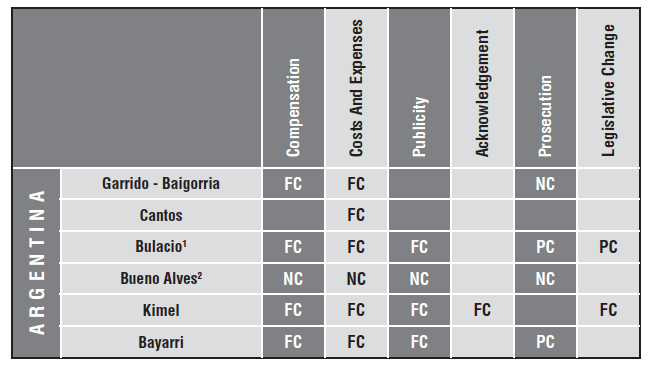

Applying the methodology used in the study published last year, we can classify the measures demanded of the State into six categories: compensation; payment of costs and expenses; publicizing the court sentence; public acknowledgement of responsibility; prosecution and punishment of those responsible; and modification of national legislation. Based on this classification system, we can observe that the State was ordered to pay compensation five times; to pay expenses in all six cases; to publicize the verdict in four cases; to publically recognize its responsibility in one instance; to modify its internal legislation twice –one of those times with more specificity than the other; and to investigate human rights violations and prosecute those responsible on four occasions.

This data can be seen graphically in the following table that we developed. It shows whether the actions demanded by the IACHR Court have been fully complied with (FC), partially complied with (PC) or not complied with (NC).

The degree to which the State complies with the sentences can be determined based on this data. However, the reparations ordered in the “Bueno Alves” decision (payment of compensation and expenses as well as publicizing the decision) should not be considered because, as mentioned earlier, the data is not yet available.

It can be observed that the State has begun to comply in some respects. It has paid compensation in four of the remaining cases; it has paid costs and expenses in five cases; it has publicized the court decision in three cases; it has publically acknowledged its responsibility the one time that it was ordered to do so; it has modified its internal laws according to the verdict that ordered specific changes; and it has partially complied with the generic changes ordered by the other decision (CORTE INTERAMERICANA DE DERECHOS HUMANOS, Caso Garrido y Baigorria v. Argentina, 2007b; Caso Bulacio v. Argentina, 2008c; Caso Cantos v. Argentina, 2010a; Caso Kimel v. Argentina, 2010b; Caso Bayarri v. Argentina, 2010c).

On the other hand, the State has not complied with its obligation to prosecute those responsible for human rights violations in any of the cases in which this was ordered. The same outcome can be expected for the “Bueno Alves” case, since –as we will explain later—the CSJN decided to ignore that sentence from the IACHR Court.

However, non-compliance with the obligation to conduct a judicial investigation is hardly surprising, given that it is the common denominator amongst all IAHRS member states that refuse to comply with IACHR Court decisions. As we explained in a previous publication (GONZÁLEZ-SALZBERG, 2010, p. 128-130), the obligation to prosecute the responsible individuals was imposed in 42 cases (of the 70 verdicts that were analyzed), and as of the end of 2008, none of these sentences had been satisfactorily fulfilled. Of all of the measures imposed, this clearly represents the one that has the highest percentage of non-compliance, at 73.8% of cases. The first instance of compliance by a State was only recorded in 2009 (CORTE INTERAMERICANA DE DERECHOS HUMANOS, Caso Castillo Páez v. Perú, 2009) and as of mid 2011 this continues to be the only exception to the general rule of non-compliance.

This brings us to reinforce the hypothesis presented in the previous section: that to guarantee compliance with the decisions issued by the IACHR Court, it is indispensable for the judicial powers of the IAHRS member states to recognize the binding nature of the Inter-American Court decisions. In this context, this study will proceed to analyze the ups and downs of the CSJN with regard to the implementation of international law in general, and then analyze the position of the CSJN with regard to the IACHR Court in particular.

Since its establishment in 1863, the CSJN has been able to directly apply international law to the cases that it has heard. The 1853 Constitution empowered the CSJN and the lower courts to address cases governed by treaties with foreign nations (Article 97 in the original 1853 text) while establishing the original jurisdiction of the highest court over issues concerning foreign ambassadors, ministers, and consuls (Article 98 in the 1853 text). This constitutional authority, coupled with the statement made on the prosecution of crimes committed against the law of nations (Article 99 in the original), can be understood to provide express constitutional authorization for the CSJN to apply general international law (MONCAYO et al., 1990, p. 69). Furthermore, Law 48, approved in 1863, specifically recognized the applicability of international law in general, when it established that the CSJN should proceed according to the law of nations when hearing cases related to foreign diplomats, and when it included in Article 21 the obligation of all national judges to apply international treaties and the principles of the law of nations.

As a result, the CSJN has applied the customary rules of international law numerous times since the 19th century without encountering problems (ARGENTINA, Gómez, Avelino c/ Baudrix, Mariano,1869). With regard to the implementation of international treaties in particular, it is clear that—in addition to the aforementioned references—Article 31 of the Constitution recognized them as an integral part of the supreme law of the land.

The difficulty is found in the questionable hierarchy given to international law by Law 48. In the aforementioned Article 21, this law established that national judges were obliged to apply norms in the following order of priority: the Constitution, national laws, international treaties, provincial laws, the laws that previously governed the nation, and principles regarding the rights of persons.

However, issues could not always be easily resolved when the Argentine legislation came into conflict with the international obligations assumed by the State. In 1963, the CSJN created a doctrine to deal with such situations. That year, the CSJN issued the “Martín and Cía.” verdict, in which it decided that there was no legal basis for determining the relative rank of laws and treaties, and therefore any conflicts between them should be resolved by applying the hermeneutic principle, which states that later norms supersede previous ones (ARGENTINA, Martín y Cía. Ltda. S.A. c/ Administración General de Puertos, 1953, párr. 6, 8).

It is worth highlighting that the basis for this decision was questionable, given the court’s fallacious assertion that there was no legal basis to resolve the hierarchical conflict between treaties and laws. The CSJN should have acknowledged the existence of contradictory normative foundations that prioritized both kinds of norms. On the one hand, Law 48 placed national laws above treaties. At the same time, when the verdict was issued, there was an indisputable customary rule of international law that affirmed the hierarchical superiority of treaties over national laws. The Permanent Court of International Justice had ruled along these lines (PERMANENT COURT OF INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE, 1930, p. 32), stating that the primacy of international law over the national laws of the States included primacy over the national Constitution (PERMANENT COURT OF INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE, 1932, p. 24).

The doctrine established through “Martín and Cía.” was not modified until 1992, when the “Ekmekdjian c/ Sofovich” decision was issued. By then, the CSJN understood that the inexistence of a normative basis for determining the hierarchy between treaties and laws was false – although that had also been the case in 1963. The court noted that in early 1980, the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties had entered into effect, and it required Member States to give preference to international law over national law. As a result, the CSJN decided that it was within its jurisdiction to prevent a violation of this Convention, given that the State might otherwise be held accountable internationally (ARGENTINA, Ekmekdjian, Miguel Ángel c/ Sofovich, Gerardo y otros, 1992, párr. 18-19).3

After the aforementioned doctrine had been established, it remained unclear what position the court would take in a future conflict between an international treaty and the National Constitution. While it has already been mentioned that from the perspective of international law, the imposed solution is the primacy of a treaty (PERMANENT COURT OF INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE, 1930, 1932), the CSJN did not concur with that interpretation. That became clear in 1993, when the CSJN issued its decision in the “Fibraca” case. In that decision the CSJN maintained that international law could only prevail over national law once the constitutional principles of public rights had been assured (ARGENTINA, Fibraca Constructora SCA c/ Comisión Técnica Mixta de Salto Grande, 1993, párr. 3). This conclusion drew on Article 27 of the Constitution, which establishes the obligation to secure relationships with foreign States through the signing of treaties so as long as they conform to the principles of public rights enshrined in the Constitution.

Still, the CSJN has not issued a categorical statement about the way in which a hypothetical conflict between national law and customary international law should be resolved. Given the principle of legal equivalency that generally governs international law (BROWNLIE, 1998, p. 3-4), one might expect that the court would give international customary law the same rank as that given to international treaties.

Thus, the doctrine of constitutional supremacy has been clearly established throughout the history of CSJN jurisprudence. It is worth recalling the extraordinary exception of the 1948 decision in the “Merk” case, where the court ruled that the Constitution only prevails over international laws in times of peace, whereas the opposite would be true in times of war (ARGENTINA, Merk Química Argentina S.A. c/ Nación, 1948). However, this ruling is only an isolated case within CSJN jurisprudence.

Perhaps the most relevant instance where a treaty was said to outrank the National Constitution can be found in 1860. In that year, the Constitution was reformed for the first time, as a result of the annexation of the state of Buenos Aires into the Argentine Confederation (ESCUDÉ; CISNEROS, 1998). The reform arose from a treaty signed between the Parties in 1859. Known as the “Pact of San José de Flores”, the treaty provided a political basis for modifying a constitution that otherwise could not be reformed for ten years (so, until 1863) due to the provisions of Article 30. However, this case is also atypical, and it occurred before the existence of a CSJN that could evaluate its validity.

By way of conclusion, it can be stated that, despite the existence of these two exceptions, it is clear that up until the 1994 constitutional reform, the CSJN gave higher status to the Constitution relative to any international law. A logical consequence of this doctrine of constitutional supremacy was the recognition of the CSJN as the ultimate arbiter, in accordance with the Constitution. The CSJN’s use of the doctrine of constitutional supremacy sets a clear limit on the possibility of the CSJN recognizing the binding nature of a decision issued by an international court, especially a decision that imposes a standard not accepted by the CSJN. However, the 1994 constitutional reform may have weakened this seemingly rigid doctrine.

The constitutional reform of 1994 not only provided a constitutional basis for the supremacy of treaties over national laws, in the new Article 75 subpoint 22; it also established that 11 international human rights instruments, listed in the Constitution itself, take precedence over the Constitution.4 Similarly, the constitutional clause established that other human rights agreements could also have precedence, with the vote of two thirds of the members of both chambers of Congress.5

This reform is extremely important for the topic at hand, because the American Convention on Human Rights (ACHR) is one of the international instruments that were given constitutional hierarchy, and this had an impact on the jurisprudence of the CSJN when it came to applying the ACHR. Notably, the ACHR is the only international instrument that establishes the jurisdiction of an international court with the power to issue binding rulings on States. Therefore, we will proceed to analyze in detail the implications of the constitutional hierarchy given to the ACHR.

In this context, it should be noted that the Constitution maintains that the listed instruments “… under the conditions of their validity, do not repeal any article from the first part of this Constitution, and should be understood as complementary to the rights and guarantees recognized herein.” (ARGENTINA, 1994, art. 75, inc. 22). This wording used by the Constituent Assembly has been the subject of various CSJN’s rulings, and should therefore be examined.

First, the article in question establishes that the international instruments have constitutional hierarchy under the conditions of their validity. As presented in the Constituent Assembly debates, this expression refers to the fact that the treaties acquire this status in accordance with the reservations and interpretative declarations that the Argentine state made at the time of ratifying or approving them (ARGENTINA, 1994, p. 2836).

However, since 1995 the CSJN has attributed a different meaning to this expression; a meaning that is quite relevant and does not contradict the intentions of the Constituent Assembly. When the court resolved the “Giroldi” case, it ruled that the conditions of validity of the ACHR should be understood to include how that treaty actually applies in the international context, particularly its implementation by international courts (ARGENTINA, Giroldi, Horacio David y otros, 1995a, párr. 11). Similarly, in the “Bramajo” case the following year, the court ruled that the reports of the IACHR Court also determined the conditions of validity of the ACHR (ARGENTINA, Bramajo, Hernán Javier, 1996a, párr. 8). Nevertheless, two years later the CSJN ruled that this did not mean that the recommendations issued by the IACHR Court were binding for the judicial powers of the State (ARGENTINA, Acosta, Claudia Beatriz y otros, 1998a, párr. 13).

This legal interpretation should be considered wise, in so far as it considers the declarations of treaties’ regulatory bodies to be relevant to the conditions of the treaties’ validity.6 Specifically, it is the only interpretation that explains why the First Optional Protocolto the International Covenant onCivil and Political Rights was granted constitutional status, even thoughits only function is to recognize the competence of the Human Rights Committee to receive individual complaints regarding violations of human rights listed in the Covenant. A different interpretation—one that concluded that the declarations of the regulatory bodies do not determine the conditions of validity of the treaties—would make the concession of constitutional status to the aforementioned Covenant nonsensical.

The second characteristic established by Article 75, subpoint 22, is that the listed instruments have constitutional hierarchy. Surprisingly, the interpretation of this phrase presented some legal discrepancies, even though the intentions of the Constituent Assembly had been clear. According to the Constituent Assembly, the listed treaties were not being incorporated into the Constitution itself; rather, they were given equal status (ARGENTINA, 1994, p. 2851). However, the CSJN has, in some case, interpreted Article 75, subpoint 22, as effectively incorporating the listed international instruments into the Constitution (ARGENTINA, García Méndez, Emilio y Musa, María Laura, 2008, párr. 7, 13), and in other cases as simply providing equal rank of these instruments, outside of the Constitution itself (ARGENTINA, Quaranta, José Carlos, 2010a, párr. 16, 24).

The next clause under consideration establishes that the international instruments do not repeal any article from the first part of the Constitution. This is undoubtedly the clause that has generated the most divergent views in doctrine and jurisprudence, since it has been understood to determine the hierarchical relationship between international instruments that have constitutional status and the Constitution itself. Within the CSJN, conflicting criteria persist today with regard to how this phrase should be interpreted when resolving cases where the Constitution appears at odds with an international instrument that technically has the same hierarchical status, such as the ACHR.

After the constitutional reform, member Elisa Carrió stated that do not repeal was an affirmation by the Constituent Assembly, which, having reviewed the different international instruments, concluded that there was no conflict between them and the first part of the Constitution. Therefore, the compatibility of both normative bodies would not be subject to judicial review (CARRIÓ, 1995, p. 71-72). This opinion was initially taken up by CSJN in 1996 when hearing the “Monges” case (ARGENTINA, Monges, Analía M. c/ U.B.A, 1996b, párr. 20-21), and it appeared to gain traction as the majority opinion in 1998 (ARGENTINA, Cancela, Omar Jesús c/ Artear SAI y otros, 1998b, párr. 10).7

Furthermore, the 1996 decision maintained that while the Constituent Assembly’s language on do not repeal referred only to the dogmatic part of the Constitution, the same concept should be applied to the organic part (ARGENTINA, Monges, Analía M. c/ U.B.A, 1996b, párr. 22).8 While the judges did not offer a clear basis for this, it may have emerged from the simple fact that the Constituent Assembly lacked the power to alter the hierarchy of different clauses within the Constitution, in accordance with Law 24.309, which identified the need for the reform and provided the authorization to carry it out. In particular, this law had restricted which articles of the Constitution could be reformed, noting that any unauthorized changes would be nullified. As a result, an interpretation other than the one made by the CSJN would lead one to think that treaties with constitutional hierarchy could “repeal” the organic part of the Constitution, thereby creating three different levels of hierarchy covering the first part of the Constitution, treaties with constitutional status, and the second part of the Constitution – an alternative that was closed to the Constituent Assembly.9

On the other hand, the dissenting opinion by Judge Belluscio in the “Petric, Domagoj” case (ARGENTINA, Petric, Domagoj Antonio c/ diario Página 12, 1998c, párr. 7) used a different interpretation of the do not repeal criteria. According to this opinion, treaties that had constitutional hierarchy would be constitutional norms of second rank, valid only when they did not contradict norms contained in the first part of the Constitution.10

Without losing sight of these two contradictory positions adopted within the CSJN, we find it necessary to examine the minutes of the Constituent Assembly. These minutes demonstrate that the expressiondo not repeal was included only near the end of the final discussion that preceded the vote. The minutes do not indicate that claims were made as to the absolute compatibility between the constitutional clauses and all of the contents of the international treaties. On the contrary, it appears that the “do not repeal” text arose from the aforementioned prohibition found in the law that initiated the constitutional reform, which prevented, under threat of nullification, any modification to the first part of the Constitution (ARGENTINA, 1994, p. 2836-2837, 3013). We believe that this is the basis for the inclusion of the words in question and that it is intimately tied to the characteristic ofcomplementarity that is given to international treaties.

Article 75, subsection 22 of the Constitution affirms that the instruments should be understood ascomplementary to other constitutional rights. As the Constituent Assembly argued, this could be considered the key to resolving any conflict that emerges between a treaty that has constitutional hierarchy and the Constitution itself. The term “complementary” was used to ensure that the correct interpretation was made clear: in case of any normative conflict, the decision that was most favorable to the rights of the person should prevail. In other words, the interpretive guideline established by the Constituent Assembly was the pro homine principle, which is used as a hermeneutic rule in various instruments that were given constitutional hierarchy (CONVENCIÓN NACIONAL CONSTITUYENTE, 1994, p. 2837-2838, 2857). This interpretation appears to be accepted today by the CSJN (ARGENTINA, Gottschau, Evelyn Patrizia c/ Consejo de la Magistratura de la Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, 2006a, párr. 10).

In light of this, the affirmation of the existence of hierarchical relationships between the Constitution and constitutionally-ranked treaties starts to lose importance, given that the constitutionally-established rule is that the norm that offers the greatest protection to the rights of the people is the one that should be applied. Judge Zaffaroni seems to have interpreted it the same way; in recent years he has maintained that any constitutional clause that causes injury—according to a pro homineinterpretation—to human rights recognized in treaties that have constitutional hierarchy should be considered inapplicable (ARGENTINA, Maza, Ángel E., 2009b, párr. 8).

It can be said that various international human rights instruments, including the ACHR, became recognized as norms of the highest rank in the Argentine legal system following the 1994 constitutional reform. Similarly, this reform gave the IACHR Court special status, as it is the only international court whose decisions are acknowledged to be binding under a rule of constitutional standing.

As mentioned earlier, the CSJN has understood since 1995 that the case law of the IACHR Court should serve as a guide for the correct interpretation of the ACHR (ARGENTINA, Giroldi, Horacio David y otros, 1995a). This doctrine is clearly established through multiple CSJN decisions, which have stressed the inescapability of IACHR Court jurisprudence when interpreting the compatibility of national law and the ACHR (ARGENTINA, Videla, Jorge Rafael y Massera, Emilio Eduardo, 2010b, párr. 8).

The CSJN’s stance has also evolved to the point where today it understands that the criteria laid out by the IACHR Court in cases involving other States are not only relevant for interpretive purposes, but could also be seen as binding on the State. Various judges have therefore invoked the jurisprudence of the IACHR Court, with the understanding that they were doing it to fulfill an international obligation. This trend can be observed in way in which various ministers voted during the resolution of the “Simón” case (ARGENTINA, Simón, Julio Héctor y otros, 2005);11 as well as in the majority vote for the “Mazzeo” decision (ARGENTINA, Mazzeo, Julio Lilo y otros, 2007a, párr. 36).12

On the other hand, there is clearly criticism within the CSJN regarding the way in which it has applied the case law of the IACHR Court, and international law in general, in cases related to the punishment of crimes against humanity. This conclusion can be drawn by looking at the dissenting opinion of Judge Fayt in the aforementioned “Mazzeo” case (ARGENTINA, Mazzeo, Julio Lilo y otros, 2007a, párr. 22, 37). In this respect, one may share the judge’s concern that the statements of certain judges could indicate some degree of ambiguity with regard to the difference between international custom and the rules of jus cogens13 and also with regard to the precise moment in which international treaties enter into force.14

However, this should not be seen as an obstacle to considering these CSJN decisions to be legally sound, given that the obligation to prosecute the crimes of the State is obviously mandatory (GONZÁLEZ-SALZBERG, 2008, p. 460-461). Similarly, the position of the CSJN should not be questioned, in light of the binding nature of IACHR Court decisions.

On the contrary, concerns should arise when contradictions are observed between the CSJN’s assertions of the binding nature of IACHR Court decisions and its failure to comply with the judgments against the Argentine State. It is therefore worthwhile to analyze how the CSJN has behaved in particular cases where it has become involved after a sentence was imposed by the IACHR Court.

The CSJN has intervened, through its decisions, following convictions by the IACHR Court in the “Cantos”, “Bulacio” and “Bueno Alves” cases. The CSJN was also involved by virtue of provisional measures issued in the “Mendoza Prisons” matter. However, its conduct is far from showing the adoption of uniform criteria; rather, its ocnduct is characterized by contradiction: sometimes recognizing the binding nature of the IACHR Court and other times refusing to carry them out.

In the “Cantos” case (CORTE INTERAMERICANA DE DERECHOS HUMANOS, Caso Cantos v. Argentina,2002), the IACHR Court had ruled against the State, determining that the plaintiff had been denied the right of access to justice given the amount of money he owed after he lost a legal complaint against the State. As a result, the IACHR Court ruled that the State should adopt different measures such as waiving the legal expenses and fines, covering the fees paid to the professionals involved, and setting “reasonable amounts” for these fees, lower than the rates established by the CSJN.

After the ruling, the Attorney General for the National Treasury appeared before the CSJN so that the court would proceed with its implementation. However, the CSJN argued that its involvement was unnecessary for fulfilling some of the provisions, and that it would not comply with the demand to reduce the fees paid to professionals because that would violate the rights of the professionals who were involved during the trial at the national level (ARGENTINA, Cantos, José María, 2003). Thus, the CSJN expressly refused to comply with the orders of the IACHR Court. Nevertheless, we note that there were two dissenting opinions, although only Judge Maqueda explicitly stated that the entire IACHR Court decision should be complied with (ARGENTINA, Cantos, José María, 2003, párr. 16).

The CSJN’s stance was very different after the verdict in the “Bulacio” case (CORTE INTERAMERICANA DE DERECHOS HUMANOS, Caso Bulacio v. Argentina, 2003). In that case, the IACHR Court had ordered the State to undertake various measures, including an investigation of the events surrounding the death of a juvenile, Walter Bulacio, after his illegal detention by the police. The Court had emphasized that, for this purpose, the statute of limitations that had been issued by the national courts were impermissible.

At the end of 2004, the complaint filed against one of those accused of the Bulacio crime came before the CSJN so that it could rule on the statute of limitations that was issued by the lower courts. The CSJN issued a ruling of great significance, maintaining that, as the IACHR Court had decided, the statute of limitations could not be considered to have expired. The ruling was especially relevant because the members of the Court did not fully agree with the judicial criteria employed by the IACHR Court, and they listed several critiques of the procedure that was undertaken in that international forum. Nonetheless, the CSJN decided that it was necessary, in principle, to subordinate their decisions to the rulings of the IACHR Court given the binding nature of the decisions issued by that Court (ARGENTINA, Espósito, Miguel Ángel , 2004b).

The real importance of this decision lies in the existence of the aforementioned tension between the judicial opinion of the CSJN and the ruling of the IACHR Court. This represents an important difference compared to previous decisions, where the binding nature of the jurisprudence of the IACHR Court had not implied any need to go against the legal criteria employed by the CSJN itself. Therefore, it can be said that the “Espósito” case is the one that shows the unquestionable recognition of the binding nature of the IACHR Court decisions and mandatory compliance by the CSJN.

However, the CSJN behaved in a completely contradictory way shortly thereafter. In the “Bueno Alves” case, (CORTE INTERAMERICANA DE DERECHOS HUMANOS, Caso Buenos Alves v. Argentina, 2007a) the IACHR Court established the obligation of the Argentine State to investigate the alleged torturing of a plaintiff in police headquarters and to punish those responsible. However, barely two months after the IACHR Court’s ruling, the CSJN decided to rule that the statute of limitations had run for the primary defendant in the case (ARGENTINA, Derecho, René Jesús, 2007b). This adhered to the opinion of the Attorney General, which was issued prior to the decision of the IACHR Court. This opinion had stated that the statute of limitations should be upheld since that the allegations did not constitute a crime against humanity. The Attorney General felt that his opinion was compatible with the jurisprudence of the IACHR Court, which would only inhibit statutory limitations for crimes against humanity, understanding that crimes using this typology were equivalent to serious human rights violations (ARGENTINA, Derecho, René Jesús, 2006b).

Thus, in 2007, the CSJN ignored the IACHR Court decision, failing even to make reference to it in its own ruling. This was a drastic departure from the position adopted during the resolution of the “Espósito” case in 2004, and it deserved, at the very least, a clear explanation.

Finally, although the issue of the “Mendoza Prisons” was not the subject of a judgment on the merits by the IACHR Court, the CSJN intervened in the case. This happened after three provisional measures were issued, which required the adoption of urgent measures to protect the lives and physical integrity of the individuals detained in prisons in the Mendoza province (CORTE INTERAMERICANA DE DERECHOS HUMANOS, Asunto de las Penitenciarías de Mendoza respecto Argentina, 2004, 2005, 2006).

In its first intervention, the CSJN required that the national and provincial governments submit information on the provisions adopted in order to comply with the IACHR Court’s instructions (ARGENTINA, Lavado, Diego Jorge y otros c/ Mendoza, Provincia de y otros, 2006c). Subsequently, the CSJN decided to require that the Executive Branch adopt adequate measures to protect the lives, health, and physical integrity of all of the prisoners, within twenty days. It also required that the provincial court block any order that was issued that could imply a violation of the human rights of the detainees (ARGENTINA, Lavado, Diego Jorge y otros c/ Mendoza, Provincia de y otros, 2007c).

This final intervention by the CSJN represents a clear step in the direction of the case law set out in “Espósito”. However, the significance of this decision, in terms of the recognition of the binding nature of the IACHR Court’s judgments, is very different from the previous case. That is because in this instance there was no tension between the measures called for by the IACHR Court and the criteria of the CSJN; the CSJN understood the need for action given the gravity of the situation (ARGENTINA,Lavado, Diego Jorge y otros c/ Mendoza, Provincia de y otros, 2006c; Lavado, Diego Jorge y otros c/ Mendoza, Provincia de y otros, 2007c).

This study provided a concise analysis of the evolution of CSJN case law with regard to the implementation of international laws. The goal was to examine the changes in doctrine undergone by the court, in order to understand its position with respect to the obligations emerging from the IAHRS. The jurisprudential history showed a marked tendency toward the protection of the principle of constitutional hierarchy, followed by the self-recognition of the CSJN as the highest court.

An important change in this legal paradigm occurred with the 1994 constitutional reform. The concession of superior status to several international human rights instruments, including the ACHR, created an important opening for the fulfillment of international obligations—particularly those emerging from the IAHRS. However, the CSJN has been inconsistent in its recognition of the binding nature of IACHR Court decisions, even though this obligation comes both from the authority of an international treaty and from a clause of the utmost rank within the Argentine legal system.

Given the fluctuations in the case law, it is hard to predict if the CSJN will end up sticking to the position that recognizes that when it comes to human rights, the ultimate legal interpreter is not the CSJN but rather the IACHR Court. This possibility can be glimpsed in the “Espósito” precedent and the position held by Judge Zaffaroni in the “Maza” case (ARGENTINA, Maza, Ángel E., 2009b, párr. 8), when he prioritized the implementation of the ACHR over the Constitution because of an interpretationpro homine of the rights in question.

As expressed at the beginning of this article, the greatest weakness of the IAHRS today is the failure of national courts to fulfill their obligation to prosecute those responsible for human rights violations, and the Argentine state is hardly the exception. The only conceivable way to overcome this situation would be for the CSJN itself to abandon positions like the one taken in response to the verdict in the “Bueno Alves” case and instead revert to the doctrine set out in the “Espósito” decision in response to the “Bulacio” verdict.

1. It can be debated as to whether the obligation imposed by the IACHR Court in this case was strictly to undertake legislative reform. Certainly it did not create an obligation to change a specific norm; instead, the Court accepted the parties’ agreement to set up a consultative group to evaluate possible changes to the law (CORTE INTERAMERICANA DE DERECHOS HUMANOS, Caso Bulacio v. Argentina, 2003, par. 144).

2. By mid-2011, the IACHR Court still had not issued any statement on its oversight of the status of compliance with this decision.

3. Another argument used by the Court in this case was that international treaties could be considered complex federal acts, given that both the Executive Branch and the Legislative Branch are involved in concluding them. The Court therefore maintained that the repeal of a treaty by only one of these branches of government would violate constitutionally conferred powers.

4. These instruments are: the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man; the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; the American Convention on Human Rights; the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights; the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; the First Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide; the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination; the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women; the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment; and the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

5. This occurred in 1997, with the Inter-American Convention on the Forced Disappearance of Persons, and in 2003 with the United Nations Convention on the Non-Applicability of Statutory Limitations to War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity.

6. In this sense, Judges Petracchi and Fayt have stated that similar treatment should be given to the doctrine established by the Human Rights Committee and the Committee Against Torture, given that these are the regulatory bodies for the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment, respectively (ARGENTINA, Trejo, Jorge Elías c/ Stema S.A. y otros, 2009a, párr. 5).

7. This happened in 1996 when Judge Vázquez – who had been the first to uphold the primacy of the Constitution over treaties with equal status (ARGENTINA, Méndez Valles, Fernando c/ A. M. Pescio S.C.A., 1995b) – adopted the opinion already held by four other judges. This created a five-judge majority that shared the same understanding of Article 75 subpoint 22. However, Judge Vázquez reverted to supporting the primacy of the Constitution in 2004, with the “Arancibia Clavel” decision (ARGENTINA, Arancibia Clavel, Enrique Lautaro y otros, 2004a).

8. A hint of a contrary view can be seen in the CSJN’s ruling in the “Felicetti” case (ARGENTINA, Felicetti, Roberto y otros, 2000, párr. 10), which indicates that the first part of the Constitution is hierarchically above both constitutionally-ranked treaties and the second part of the Constitution, giving the latter two the same hierarchical status.

9. The possibility that a clause modified by the Constituent Assembly could be declared null and void is far from being a mere hypothetical exercise. It occurred in 1999, when the CSJN determined that the Constituent Assembly had overstepped their role (ARGENTINA, Fayt, Carlos Santiago c/ Estado Nacional, 1999).

10. This dissenting opinion by Judge Belluscio would later be echoed by Judge Fayt in his dissenting opinion in the “Arancibia Clavel” case (ARGENTINA, Arancibia Clavel, Enrique Lautaro y otros, 2004a, párr. 15, 24, 32). Judges Zaffaroni and Highton seem to have applied similar criteria to their votes in the same case, when they found a conflict between the Constitution and a treaty with constitutional status and opted not to apply the latter (ARGENTINA, Arancibia Clavel, Enrique Lautaro y otros, 2004a, párr. 22, 33).

11. In particular, it emerges from the opinions of judges Petracchi (ARGENTINA, Simón, Julio Héctor y otros, 2005, párr. 24), Zaffaroni (ARGENTINA, Simón, Julio Héctor y otros, 2005, párr. 26), and Highton (ARGENTINA, Simón, Julio Héctor y otros, 2005, párr. 29).

12. The binding nature of IACHR Court jurisprudence has also been used by Judge Petracchi to justify changes in previously-held opinions, particularly his refusal to extradite a Nazi war criminal (ARGENTINA, Arancibia Clavel, Enrique Lautaro y otros, 2004a, párr. 22- 23) and the validation of the law of due obedience (ARGENTINA, Simón, Julio Héctor y otros, 2005, párr. 13-14, 30).

13. This can be seen in the votes of Judge Zaffaroni and Judge Highton in the “Arancibia Clavel” case (ARGENTINA, Arancibia Clavel, Enrique Lautaro y otros, 2004a, párr. 28); in Judge Zaffaroni’s vote in the “Simón” case (ARGENTINA, Simón, Julio Héctor y otros, 2005, párr. 27); and in Judge Lorenzetti’s vote in the same case (ARGENTINA, Simón, Julio Héctor y otros, 2005, párr. 19).

14. In particular, with Judge Highton’s vote in the “Simón” case (ARGENTINA, Simón, Julio Héctor y otros, 2005, párr. 22).

Bibliography and other sources

ARGENTINA. 1994. Convención Nacional Constituyente. 22ª Reunión – 3ª Sesión Ordinaria. 2 de agosto de 1994. Versión taquigráfica.

BASCH, F. et al. 2010. La efectividad del Sistema Interamericano de Protección de Derechos Humanos: un enfoque cuantitativo sobre su funcionamiento y sobre el cumplimiento de sus decisiones. Sur – Revista Internacional de Derechos Humanos, São Paulo, v. 7, n. 12, p. 9-35, jun. 2010.

BROWNLIE, I. 1998. Principles of International Law. 5. ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

CARRIÓ, M.E. 1995. Alcance de los tratados en la hermenéutica constitucional. En: CARRIÓ, M.E. et al. Interpretando la Constitución. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Ciudad Argentina. p. 51-72.

ESCUDÉ, C.; CISNEROS, A (Dir.). 1998. Historia General de las Relaciones Exteriores de la República Argentina. Buenos Aires: GEL. Available at: http://www.ucema.edu.ar/ceieg/arg-rree/historia_indice00.htm. Last accessed on: 2 jul. 2011.

GONZÁLEZ-SALZBERG, D. 2008. El derecho a la verdad en situaciones de post-conflicto bélico de carácter no-internacional. International Law: Revista Colombiana de Derecho Internacional, Bogotá, n. 12, p. 435-468, Edición Especial.

_____. 2010. The effectiveness of the Inter-American Human Rights System: a study of the American State’s compliance with the judgments of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. International Law: Revista Colombiana de Derecho Internacional, Bogotá, n. 15, p. 115-142, June.

MONCAYO, G. et al. 1990. Derecho Internacional Público. 3. reimpresión. Buenos Aires: Zavalía.

Jurisprudence

ARGENTINA. 1869. Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación. Gómez, Avelino c/ Baudrix, Mariano. Fallos 7:282.

_____. 1948. Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación. Merk Química Argentina S.A. c/ Nación. Fallos 211:162.

_____. 1953. Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación. Martín y Cía. Ltda. S.A. c/ Administración General de Puertos. Fallos 257:99, párr. 6 y 8.

_____. 1992. Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación. Ekmekdjian, Miguel Ángel c/ Sofovich, Gerardo y otros. Fallos 315:1492, párr. 18 y 19.

_____. 1993. Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación. Fibraca Constructora SCA c/ Comisión Técnica Mixta de Salto Grande. Fallos 316:1669, párr. 3.

_____. 1995a. Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación. Giroldi, Horacio David y otros s/ recurso de casación – causa n° 32/93. Fallos 318:514, párr. 11.

_____. 1995b. Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación. Méndez Valles, Fernando c/ A. M. Pescio S.C.A. s/ ejecución de alquileres. Fallos 318:2639, voto del juez Vázquez.

_____. 1996a. Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación. Bramajo, Hernán Javier s/ incidente de excarcelación– causa n° 44.891. Fallos 319:1840, párr. 8.

_____. 1996b. Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación. Monges, Analía M. c/ U.B.A. –resol. 2314/95. Fallos 319:3148, párr. 20 y 21.

_____. 1998a. Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación. Acosta, Claudia Beatriz y otros s/ hábeas corpus. Fallos 321:3555, párr. 13.

_____. 1998b. Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación. Cancela, Omar Jesús c/ Artear SAI y otros. Fallo 321:2637, párr. 10.

_____. 1998c. Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación. Petric, Domagoj Antonio c/ diario Página 12. Fallos 321:885, disidencia del juez Belluscio, párr. 7.

_____. 1999. Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación. Fayt, Carlos Santiago c/ Estado Nacional s/ proceso de conocimiento. Fallos 322:1641.

_____. 2000. Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación. Felicetti, Roberto y otros s/ revisión – causa n° 2813. Fallos 323:4130, párr. 10.

_____. 2003. Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación. Cantos, José María. Fallos 326:2968; voto conjunto de los jueces Fayt y Moliné O’Connor; voto del juez Vázquez; disidencia del juez Maqueda, párr. 16.

_____. 2004a. Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación. Arancibia Clavel, Enrique Lautaro y otros s/ asociación ilícita, intimidación pública y daño y homicidio agravado– causa n° 1516/93- B–. Fallos 327:3294, voto conjunto de los jueces Zaffaroni y Highton, párr. 22, 28 y 33; voto del juez Petracchi, párr. 22 y 23; disidencia del juez Fayt, párr. 15, 24 y 32; disidencia del juez Vázquez, párr. 26 y 27.

_____. 2004b. Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación. Espósito, Miguel Ángel s/ incidente de prescripción de la acción penal promovido por su defensa. Fallos 327:5668.

_____. 2005. Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación. Simón, Julio Héctor y otros s/ privación ilegítima de la libertad, etc. – causa n° 17.768. Fallos 326:2056, voto del juez Petracchi, párr. 13, 14, 24 y 30; voto del juez Zaffaroni, párr. 26 y 27; voto de la jueza Highton, párr. 22 y 29; voto del juez Lorenzetti, párr. 19.

_____. 2006a. Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación. Gottschau, Evelyn Patrizia c/ Consejo de la Magistratura de la Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires s/ amparo. Fallos 329:2986, párr. 10.

_____. 2006b. Procuración General de la Nación. Derecho, René Jesús s/ incidente de prescripción de la acción penal – causa n° 24.079.

_____. 2006c. Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación. Lavado, Diego Jorge y otros c/ Mendoza, Provincia de y otros s/ acción declarativa de certeza. Fallos 329:3863.

_____. 2007a. Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación. Mazzeo, Julio Lilo y otros s/ rec. de casación e inconstitucionalidad. Fallos 330:3248, voto mayoritario, párr. 36; disidencia del juez Fayt, párr. 22 y 37.

_____. 2007b. Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación. Derecho, René Jesús s/ incidente de prescripción de la acción penal – causa n° 24.079. Fallos 330:3074.

_____. 2007c. Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación. Lavado, Diego Jorge y otros c/ Mendoza, Provincia de y otros s/ acción declarativa de certeza. Fallos 330: 111.

_____. 2008. Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación. García Méndez, Emilio y Musa, María Laura s/ causa n° 7537. Fallos 331:2691, párr. 7 y 13.

_____. 2009a. Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación. Trejo, Jorge Elías c/ Stema S.A. y otros. Fallos 332:2633, voto conjunto de los jueces Petracchi y Fayt, párr. 5.

_____. 2009b. Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación. Maza, Ángel E. s/ amparo medida cautelar. Fallos 332:2208, voto del juez Zaffaroni, párr. 8.

_____. 2010a. Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación. Quaranta, José Carlos s/ inf. Ley 23.737 – causa n° 763. Fallos 333:1674, párr. 16 y 24.

_____. 2010b. Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación. Videla, Jorge Rafael y Massera, Emilio Eduardo s/ recurso de casación. Fallos 333:1657, párr. 8.

CORTE INTERAMERICANA DE DERECHOS HUMANOS (CORTE IDH). 1996. Sentencia de 2 de febrero de 1996. Caso Garrido y Baigorria v. Argentina. Serie C No. 26.

_____. 2002. Sentencia de 28 de noviembre. Caso Cantos v. Argentina.Serie C No. 97.

_____. 2003. Sentencia de 18 de septiembre. Caso Bulacio v. Argentina. Serie C No. 100.

_____. 2004. Resolución de la Corte Interamericana de 22 de noviembre. Asunto de las Penitenciarías de Mendoza respecto Argentina.

_____. 2005. Resolución de la Corte Interamericana de 18 de junio. Asunto de las Penitenciarías de Mendoza respecto Argentina.

_____. 2006. Resolución de la Corte Interamericana de 30 de marzo. Asunto de las Penitenciarías de Mendoza respecto Argentina.

_____. 2007a. Sentencia de 11 de mayo. Caso Buenos Alves v. Argentina. Serie C No. 164.

_____. 2007b. Supervisión de Cumplimiento de Sentencia. Resolución de la Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos de 27 de noviembre.Caso Garrido y Baigorria v. Argentina.

_____. 2008a. Sentencia de 2 de mayo. Caso Kimel v. Argentina. Serie C No. 177.

_____. 2008b. Sentencia de 30 de octubre. Caso Bayarri v. Argentina. Serie C No. 187.

_____. 2008c. Supervisión de Cumplimiento de Sentencia. Resolución de la Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos de 26 de noviembre. Caso Bulacio v. Argentina.

_____. 2009. Supervisión de Cumplimiento de Sentencia. Resolución de la Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos de 3 de abril.Caso Castillo Páez v. Perú.

_____. 2010a. Supervisión de Cumplimiento de Sentencia. Resolución de la Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos de 26 de agosto.Caso Cantos v. Argentina.

_____. 2010b. Supervisión de Cumplimiento de Sentencia. Resolución de la Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos de 15 de noviembre.Caso Kimel v. Argentina.

_____. 2010c. Supervisión de Cumplimiento de Sentencia. Resolución de la Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos de 22 de noviembre.Caso Bayarri v. Argentina.

PERMANENT COURT OF INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE (PCIJ). 1930. The Greco-Bulgarian “Communities”. Advisory Opinion (ser. B) No. 17 (July 31), p. 32.

_____. 1932. Treatment of Polish Nationals and Other Persons of Polish Origin or Speech in the Danzig Territory. Advisory Opinion (ser. A/B) No. 44 (feb. 4), p. 24.