Some ideas on How to Restart the Debate

Organizations from Latin America met in mid-2012 in São Paulo, Brazil to jointly carry out a diagnosis of the impact of the dominant economic development models on human rights and critically evaluate the response strategies of the human rights movement to face this challenge. This article presents some of the thinking at a meeting organized by Conectas Human Rights, the Center for Studies on Law, Justice and Society (Dejusticia) and the Law School of the Fundação Getúlio Vargas.

Although the human rights movement distanced itself from the debate surrounding economic development for a long time, in recent years interest in the subject has been rekindled. This renewed interest brings to light that true debate on the subject requires collective thinking on the conceptual and operational challenges of action.

This article presents some of the thinking at a meeting1 held in São Paulo in May, 2012. Organized by Conectas Human Rights, the Center for Studies on Law, Justice and Society (Dejusticia) and the Law School of the Fundação Getúlio Vargas, the meeting brought together Latin American organizations to jointly make a diagnosis of the impact of the dominant economic development models on human rights and critically evaluate the response strategies of the human rights movement in the face of this challenge.

This article organizes the meeting’s ideas around four areas of tension: 1.1) Development vs. economic growth; 1.2) Ecosystemic limits vs. demands for expansion of access to rights; 1.3) Property right vs. common good; 1.4) Us vs. them: new divisions and new alliances? Towards the end we include a section on thinking about how to strengthen the human rights movement’s actions on this subject and offer some conclusions.

We frequently refer to economic growth as being synonymous with development. Nevertheless, economic growth, with its obsession for material accumulation and its negligence regarding environmental impact, has generated multiple incompatibilities from a human rights perspective.

In Latin America, the current economic model’s negative impact on human rights is increasingly apparent. Even recognizing important results, such as the reduction in poverty and progress in terms of eco-efficiency and corporate social responsibility, it has become evident that mechanisms must be developed to place limits on the obsession for profit and, especially, to strengthen the State’s ability to regulate. A weak State has less defenses against market interests.

In Latin America, after decades of neoliberal policies, the return to policies of economic development has translated into greater activism on the part of the State, which has assumed a central role. In both the previous and current periods of developmental policies, the State chooses and supports economic sectors that are transformed into “winners”. Currently, it is left-wing governments in the region that take upon themselves the task of developing their countries, and, for this, they give preference to certain economic sectors. In contrast to the nineties, when the State’s role shrank, we now have stronger States that consolidate their abilities to boost certain economic sectors and yet, at the same time, reduce their abilities to regulate and control.

In this scenario, economic growth takes precedence over any other value, and even over respect for human rights, especially for more vulnerable communities. Developmental policies and culture therefore aggravate tension between the sectors who are the beneficiaries of growth and those who must pay the cost of these policies. In this way, those who criticize the model, as well as those who are affected by it, are seen as “obstacles” to the country’s growth. Repeatedly, both criminalization of those opposing these policies and denial of the rights of those affected are justified in the name of the intended collective well-being.

This tension also questions some of the characteristics of our representative democratic systems, given that the groups most often affected are very distant from the political and economic center and, consequently, face even greater difficulty making their voices and interests heard.

Part of the solution to these issues could come from finding ways of including ethics in the economy; reconciling economy and society, values and science. Amartya Sen offers a conceptual tool with which to do this. His conception of development as the expansion of the autonomous decision-making sphere of individuals (of abilities)2 allows the instrumental reconciliation of the idea of democracy with human rights. Development as individual and collective autonomy suggests an emancipating model that is not imposed from outside, but one that is internal within societies, requiring information and intense public debate. In fact, Sen’s thinking is extremely contemporary, as demonstrated by the strategies of mobilization and litigation of many organizations in reaction to the recent initiatives of open governments and national laws ensuring access to information (such as in Peru, Brazil, Mexico etc.).

Development as an expansion of abilities, therefore, makes it possible to recuperate the idea of the Democratic State and revalorize it—not as a protection mechanism for private investment, but as protection for minorities against the majorities, for example, against a certain model of development that affects their cultural identity.

Popular participation can also be a way of setting certain limits on the model centered exclusively on economic growth. Prior consultation with indigenous peoples is an example of a mechanism that can guide the formulation and implementation of public policies and that promotes development taking into consideration the reality and the rights of those affected.3

Amartya Sen enables us to link the question of human rights with that of development. However, a new dilemma arises: how to include the environmental dimension in Sen’s model?

We know that the agenda of human rights organizations is based on making access to rights universal. Nevertheless, expansion of access presupposes the permanent expansion of consumption, and today this is unsustainable. Conceptually the dilemma is to try and reconcile the need to expand access to rights for all on a planet that is host to 7 billion inhabitants and the natural resources of which have a distinct limit. In other words, how can we reconcile the imperatives of social justice with those of environmental justice? Environmental justice has a special relationship with the classic issues of redistribution and recognition.4 But, until now, the juridical nexus between human rights and the environment remains very weak (with some exceptions, such as the constitutions of Ecuador and Bolivia or the International Labor Organization Convention 169).

Additionally, neither the right nor the economy is able to provide a tool to overcome this tension. The green economy model has turned into a form of “greenwash” and has not been able to stop the trend to destruction of the planet and the exhaustion of its natural resources. The new international division of the world’s natural recourses and labor de-industrializes the economies of Latin America (and Africa) and converts them into exporters of raw materials, while Asia concentrates on manufacturing and inclusion in the world market, and Europe and the United States consume the final product. How, therefore, can natural resources be used in a way that guarantees real social needs?

A possible answer lies in changing a model in which the world is dedicated to the consumption of private goods. The meaning and use of the economy must be changed – both in theory and in practice.5 The fight against poverty cannot be won without reducing inequality, which may require, in some cases (in the more developed countries), concrete limitations on consumption.

There is, nonetheless, some cause for optimism. With the social networks, new possibilities have arisen for social cooperation (including for cooperative consumption) and collective struggle for new forms of citizenship in an overburdened planet.

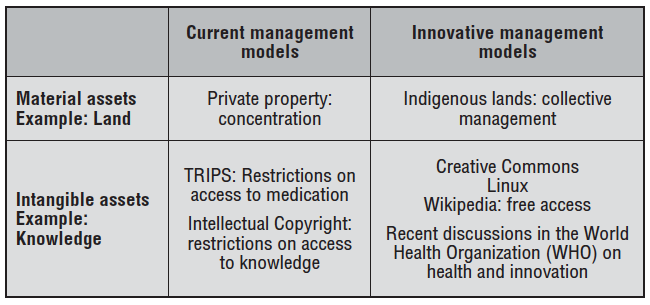

The third dilemma concerns the tensions between old and new models of the management of material commons (such as the land) and intangible commons (such as knowledge).

With the canonization of private appropriation, the liberal development model as we know it, puts at risk common assets (such as water and biodiversity) through commercialization,; this is illustrated in the intellectual property rights system’s impact on the right to health. The productive monopoly represented by the patent system not only increases the cost of medicine and makes access difficult, but it has also stifled innovation. Numerous fatal diseases in underdeveloped nations continue to be ignored.

Something similar occurs in the case of the culture industry, where intellectual property at any price makes access to information difficult, affecting, and sometimes criminalizing, artists’ and citizens’ freedom of expression.

This phenomenon implies significant challenges for the human rights movement for at least two reasons:

1) The culture industry makes use of human rights vocabulary (author’s rights) to defend private profit.

2) Many of the continent’s governments are increasing protection of intellectual property and private monopoly as a way to promote “economic growth.” Tensions between the patent system and the protection of the common good are frequent, for example, in Brazil where the Health Ministry has signed agreements with private laboratories to produce drugs – such as atazanavir – for HIV/AIDS.6

Although firmly rooted in the legal systems, individual property rights coexist with alternative models of production and collective property. Recent experiences are showing that the networks can also bring values (such as trust and reciprocity) to the system, which are fundamental to the collective management of tangible or intangible assets. As Yochai Benkler theorizes,7 the transforming potential of the new models can be seen in the advance of the internet economy in the collective management of intangible property (with experiences such as Linux, Creative Commons and Wikipedia, for example) or in the proposal of alternative models of consumption (such as Cooperative Consumption).

The concept of commons (those that are non-exclusive, which are not the property of anyone and allow shared use) can be a useful theoretical tool for questioning current models of commons management. The idea of common property not only affirms the primacy of the collective interest over individual interests, but it also specifically allows the idea of shared and collective management of some property, such as information and knowledge (pure public commons: those that are non-excluding and non-exclusive).

While communication and information technologies have allowed the expansion of the internet economy, collective management of natural resources has yet to become any substantial aspect of this debate. An important contribution is the collective management model for the lands of various indigenous peoples in Latin America. Nevertheless, studies of the economic feasibility of these collective models, as well as the question of how they can survive in economic and institutional environments where private property is predominant, need to be more thoroughly undertaken.8

Contrary to the previous dilemmas, the last point of tension refers not to the objective of protecting human rights but, rather, the human rights movement as a player in this process. Getting involved in development issues requires the movement to take a critical look at the traditional antagonisms and the traditional us-them dichotomies.

In the conceptual debate and, even more so, in the operational aspect, one can see a lack of clarity over the limits between allies and enemies. Frequently, the question of development radicalizes tensions within the human rights movement.

There is agreement over the fact that one of the movement’s main challenges is to reconcile – conceptually and strategically – the duty of protecting the rights of those affected with the imperatives of the public good. It is not, however, easy to articulate criticism of development as the latter creates an alliance between various sectors (business, financial, technocracy and some union sectors). In this context, often those criticizing this model are seen as traitors.

The tensions between some human rights organizations and a part of the union movement are a good example of this complex relationship. In mining activities or infrastructure megaprojects, the protection of workers’ interests – focused in the creation of jobs – does not always coincide with the interests of those affected, as with indigenous peoples and the local communities.

A second division arises between human rights organizations and the political left, especially in contexts in which pro-development governments come from the left. In this situation, today is common to see splits between a pro-development left and an environmentalist left.

A third division occurs in the positioning and strategies of the movement when faced with multiple challenges. While some organizations spend time questioning the collateral effects of the model (with tools such as Corporate Responsibility and strategic philanthropy), others envision a long-term goal, trying to change the structures of the economic model by attempting to produce a dialogue with alternatives going beyond the green economy. For those working with corporations, Ruggie’s soft law can be a tool.9 For others, strengthening the hard law of the courts is the best alternative.

Contradictory views arise about the role of companies in building a bridge between players in the human rights movement and the world of development. For some, the incorporation of ethics into the economy needs everybody: state and market and, for this, Corporate Social Responsibility is a necessary advance bringing important changes. Inversely, there are others who see it as a form of marketing (or greenwashing) that has only worsened the overall situation.

At the same time, some claim it possible that companies are not homogenous and that there is room to maneuver by maintaining a dialogue. Is it possible to successfully formulate strategies for working with resistance efforts and, at the same time, attempt to bring about internal change? Whatever the answer, to involve itself in the question the movement must seek legitimate interlocutors in corporations for constructive dialogue and, simultaneously, overcome the legal hurdles to justice in cases of violations involving corporations.

Beyond the conceptual complexities inherent to the area of human rights and development, we can identify some of the collective deficiencies of the human rights movement in order to work on the issue and serve as a road map for thinking about future action.

Developing conceptual tools. The first hurdle is the lack of conceptual tools thinking of alternatives to the dominant model of economic development, whether by means of the network economy, or part of the commons model. Only the systematic accumulation of evidence will allow us to construct a minimum basis of information and understanding among the region’s organizations. We must also act in a critical and purposeful manner, which includes intervening in the production of knowledge, especially in the juridical and economic sciences.

Rethinking the unity of action, the alliances and the most suitable forums. Today we need new allies and to identify increasingly trans-national spaces for the struggle. For this, we not only need strategies with proposals, but also ones that are creative (such as dialogue and litigation in other forums such as the Courts of Auditors or the creation of scientific organizations that can contribute to the investigation of human rights violations as a consequence of economic growth initiatives). We also need to form multi-sector and multidisciplinary alliances, including with technically qualified people in other areas traditionally distant from human rights (for example biology and engineering). At the same time, we need to complement the work in the traditional arenas of action (institutions of the Nation-State or the universal human rights system) with work in various action units (for example, in bio-geographical zones) in which the processes we want to challenge take place (for instance, deforestation of the Amazon, consisting of various nation-states).

Mapping installed and available capacities. Finally, the mapping of our installed capacities is crucial to finding out what we still lack. It is also important to have a panorama of the players involved in the question, enabling us a clearer vision of possible partners, interlocutors, and opponents.

The first conclusion is that there is still no consensus on a human rights agenda concerning economic development, whether among human rights organizations or between the latter and other social sectors in each of our countries. Today we are facing a new wave of violence and criminalization against those who defend alternative values and an economic growth model understood as merely the expansion of consumption.

The second conclusion is that, in this context, our actions should be primarily local and case-dependent. But, it is precisely the connection of multiple, simultaneous local actions that end up disputing the global economic structure. In this sense, the local collective action strengthens (and is strengthened by) transnational collective action.

It is now possible now to intensify networks of collaboration and dissemination of information thanks mainly to the Internet and to the social networks. Some concepts such as trust and reciprocity emerge as challenges to the old models, principally of the neoliberalism and the developmentism.

The collective perception is that the best plan of action in this context is to continue discussing our particularities and insert them in a universal discourse; we must continue to act strategically at the micro level, case-by-case, but with a clear and solid discourse of principles.

Also pending are more in-depth discussions over whether the human rights arena is suitable to deal with these questions. Some hold that the discourse of rights, due to their principle-oriented nature and absolute values, could lead to tensions without solutions. In situations where the local communities are obliged to negotiate, the rights discourse that leaves less room for trade-offs could increase the likelihood of conflict and fail to lead to real solutions.

Only an accumulation of experiences leads to sustainable transformation. We must be persistent and creative if we are to succeed in transforming practices and ideas on economic development and human rights.

1. The meeting was also seen as an opportunity to identify some issues for collective action in the short and medium terms. Taking part were 26 representatives from 24 organizations in Latin America.

2. Sen, Amartya. Development as Freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

3. See César Rodíguez Garavito. Etnicidad.gov: los recursos naturales, los pueblos indígenas y el derecho a la consulta previa en los campos sociales minados. Bogotá: Dejusticia, 2012

4. See Nancy Fraser. Justice Interruptus: Rethinking Key Concepts in a Post-socialist Age (1997), The Radical Imagination: Between Redistribution and Recognition (2003), Redistribution or Recognition? A Political-Philosophical Exchange (2003), and Scales of Justice: Reimagining Political Space in a Globalizing World (2008) y Robert Melchior Figueroa. Debating the Paradigms of Justice: The Bivalence of Environmental Justice. Ann Arbor: University Microfilms International, 1999.

5. See Ricardo Abramovay. Muito além da economia verde. São Paulo: Planeta Sustentável, 2012.

6. See Working Group on Intellectual Property (GTPI), Brazilian Network for the Integration of Peoples (REBRIP), Letter of Concern of the GTPI regarding the Public-Private Partnerships announced by the government, April 19, 2011, available at: http://www.deolhonaspatentes.org.br/media/file/Notas%20GTPI%20-%202011/Carta%20GTPI_Preocupa%C3%A7%C3%B5es_Final_Site.pdf. Last accessed at: Dec. 2012.

7. See Yochai Benkler. The Wealth of Networks. Yale: Yale University Press, 2006. Available at: http://www.benkler.org/Benkler_Wealth_Of_Networks.pdf. Last accessed at: Dec. 2012.

8. See: Juan Camilo Cárdenas, Dilemas de lo colectivo: Instituciones, pobreza y cooperación en el manejo local de los recursos de uso común. Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes, 2009. Available at: http://static.elespectador.com/archivos/2009/08/04ae547f65e425c3e20d939e355f3306.pdf. Last accessed at: Dec. 2012.

9. Reference to the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights approved by the UN Human Rights Council in March 2012. UN, Human Rights Council, Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights: endorsed by the United Nations to “protect, respect and remedy”, March 21, 2012, A/HRC/12/31. Available at: http://www.business-humanrights.org/media/documents/ruggie/ruggie-guiding-principles-21-mar-2011.pdf. Last accessed at: Dec. 2012.