Up until recently, the human rights movement has been reluctant to engage on the topic of measurement, highlighting the difficulties involved and resisting pressure from donors to comply with impact assessment standards developed in other fields. This paper argues that measurement techniques are, indeed, very problem specific and that they must be linked to a refined understanding of the mechanics of a problem. Given the need for progress on the pressing issues of human rights, it is all the more important that civil society organizations move out of their defensive position regarding measurement and begin developing models for the two large measurement challenges: (1) how do we size the problem and understand how it is developing over time? and (2) how do we understand the impact that we are having on the problem itself? This paper outlines how Civil Society Organizations can increase their effectiveness by using measurement and data to gain a clearer idea of what problem they are trying to solve, a better idea of how to mark their progress in striving toward that goal, and an understanding of what place their efforts have in a broader context of civil society problem-solvers. While addressing the specific difficulties that human rights organizations face in the process of self-evaluation, this paper proposes steps that would guide human rights organizations on the road to increasing their impact.

Over the past two decades, the playing field in human rights has changed dramatically. The number of organizations working on human rights issues has grown at a staggering pace. Civil society in many countries (excluding some large and important ones) now has a voice, and has developed instruments geared towards social change as they have witnessed an ever-expanding freedom to operate. A growing number of small, sometimes highly innovative and agile organizations have entered the playing field, while some of the larger organizations have further expanded in size, level of influence, and sophistication. As large corporations reach out to the community of citizen organizations new partnerships are becoming possible to jointly craft solutions to public problems. The internet has created opportunities to network and exchange information and ideas that would have been impossible a mere ten years ago. Some progress seems to have been made in the mainstreaming of the language of human rights in other fields. Rights-based approaches in the areas of development, health, de-mining and others have gained currency in individual governments as well as in international agencies and organizations. These trends represent a tremendous opportunity for organizations in the field of human rights.

However these rights-based approaches also represent a challenge. From the point of view of donors and volunteers, the question on where to allocate their resources has become more difficult. There are more organizations to choose from in the field of human rights, and as other fields appropriate rights-language, there seem to be more options for achieving progress on human rights issues, and fewer options for supporting organizations that are operating under an explicit human rights-banner. Donors – whether governments, foundations or individuals – are ever more determined to give their support to something that works, and regarding the communication of impact, they are becoming more demanding. So far, the human rights movement has been on the defensive, criticizing the metrics imposed upon them as missing the essence of their work. Much of this criticism is justified: an exaggerated focus on numbers and on quantifiable measures of success tends to blur the vision for current and future impact, much of which is not measurable. Take, for example, the ever increasing role of individuals known as ‘social entrepreneurs’. These are high-leverage individual change-makers, whose keys to success are their personal qualities of persistence, creativity, and alliance-building skills, combined with a genuinely new and scaleable idea, but these qualities can not be captured with a number or a plan.1

This paper argues that it is high time for the human rights community to change their defensive position of critiquing donor-imposed metrics to a more constructive one; a position in which organizations develop a combination of quantitative and qualitative impact metrics, one that they feel makes sense; and then find a method to communicate their position. If there are aspects of work that are still not quantifiable, a message must be crafted and communicated as to why those aspects remain strong levers of change. It is true that donors are interested in this agenda, and that measurement techniques for funds received are a key tool for creating accountability. It is also true, however, that impact assessment acts as a tool for creating accountability to those people in whose name and interest human rights organizations advocate for social change. Impact indicators are no more than a useful by-product in the far more fundamental process of making the mechanics of a problem transparent, and of comprehending the levers of change, which, in turn, enable the cooperation and division of labor between organizations as well as a thoughtful stewarding of resources. In short, this paper shall outline how measurement techniques for human rights organizations could be developed, and why they should develop these techniques as a matter of duty to the individuals and groups of people whose rights they are claiming to defend.

Whether described in terms of “performance measurement,” “impact evaluation,” or “organizational effectiveness,” the underlying process is the same: it is a systematic assessment by human rights organizations of where they fit into the community of problem-solvers, as well as how well they are fulfilling their own missions. None of the many reasons that are – legitimately – brought forth as limiting factors can hold up against the strong reasons that speak for it. Unless each organization is able to show that it is using the most powerful levers possible to achieve its intended outcome, and unless it understands the link between its daily actions and the goal that it is hoping to affect, progress toward the much-needed systemic change will remain too slow. As one author bluntly put it, “If you don’t care about how well you are doing something, or about what impact you are having, why bother to do it at all?”2

Due to their dependency on external funding, almost every organization with a societal mission has some sort of reporting system in place on outcomes. Over the past ten years, however, the pressure has grown on organizations of all sizes and orientations to become more explicit and outcome-oriented in communicating their effectiveness. Civil society organizations (CSOs) have been pressed to develop more transparent reporting on two levels: the internal level of organizational performance, i.e. how well the organization’s structure, resources, and processes are equipped to perform its tasks, and the external level of results, i.e. how well the organization achieves its intended impact. The issue of both internal organizational performance and that of impact measurement have been the subjects of volumes of theoretical analysis and practical research.3

A number of historical trends have driven this increased interest in the transparency and impact measurement of CSOs. One example of this is the expanding role of the CSO in regional, national, and international policymaking. Not only has the number of CSOs increased (in some parts of the world exponentially), but some CSOs have grown to a level at which they have taken on roles previously filled by government institutions, and are actively influencing policy. This has raised questions about their legitimacy as well as their authority to take advocacy actions in someone else’s name.4 Better performance metrics and more rigorous reporting on impact are hailed as vital steps towards building greater accountability and legitimacy.

Thanks to the internet and the birth of the “global information society,” there has been an increase in awareness among CSOs and in the societies in different parts of the world from which they draw their support, of the need for systemic change; making all the more necessary the judicious allocation of scarce resources. Images of human rights transgressions are beamed real-time into peoples’ living rooms, featured in films and articles, and shown in photographs. This creates a seemingly endless menu of the need for action.

At the same time, the growing salience and awareness of these problems has broadened the base of individuals and institutions that feel responsible for responding to these social needs.5 As corporations and individual entrepreneurs become involved in the social field as philanthropists, problem-solvers, and investors, their standards of accountability carry over into the sector they are newly interacting with. Evaluative and organizational concepts imported from the competitive and productivity-driven private sector are increasingly being called upon to guarantee that each dollar achieves the maximum “bang for the buck.”6 New forms of philanthropy, including ‘venture philanthropy’ and ‘social investing’ with some concepts of social return on investment (some are more refined and some less); a culture of strategic planning and impact indicators in organizations of all sizes has been created. Foundations have developed frameworks from which they can assess and communicate the impact of their grantees. Some foundations are even beginning to publicize their own performance as donors and as supporters of their grantees’ development.7

There are a number of challenges being created by this debate, which will be outlined below in more detail. A wide variety of voices are pursuing the issue with a broad range of ideas on what impact assessment should look like, forcing CSOs into the cumbersome process of evaluating their work through a variety of templates, and reporting differently to different sponsors. In addition, the transmuting of frameworks of measurement from the private sector to the civil sector is not always possible, and to provide transparent accounting of operations and impact is far more difficult in the social sphere. Creating social change is simply not as linear a process as that of producing widgets, and there are no market-mechanisms to capture and reward increases in social shareholder values.

The topic of impact assessment and organizational effectiveness has nonetheless been gaining traction in some distinct sub-sectors of civil society. A full history on the discussion of accountability and measurement would go beyond the limits of this article, but a brief overview might serve to highlight the areas in which a discussion has taken off on some of the lessons for CSOs to learn in the field of human rights.

Partially fueled by the anglo-saxon philanthropic model that closely intertwines so-called “nonprofits” with the corporate and entrepreneurial world, CSOs in the United States and the United Kingdom have been particularly engaged in the development of internal evaluation and measurement techniques. Large nonprofit umbrella organizations and CSOs, such as the United Way and Save the Children UK, have adopted systematic approaches over the past 10 years for internal evaluation and measurement, and have restructured their engagement models to engender cultures of performance among their grantees and members.8 The English-speaking academic community devoted to the study of nonprofit organizations has enthusiastically taken on this topic and produced a vast amount of literature for organizations in the nonprofit sector, providing guidelines and frameworks on how to create internal evaluation systems and become “high-performing.”9 The past 10 years have witnessed an explosion in academic research, capacity-building initiatives, and conferences regarding impact and organizational effectiveness, and a number of journals dedicated solely to these issues have sprung up.10 These trends have inspired the birth of an entire industry of performance-focused consulting firms who target foundations and nonprofits as clients.11 Strategic planning, impact assessment, and accountability are buzz-words and they have a hopeful ring of progressiveness, innovation, and quality.

Citizen sectors of the US and the British are, or course, not the only ones discussing impact measurement and accountability. By the late nineties, impact assessment was already very high on the radar screen of civil society organizations around the world, driven in part by the interest of their international funding partners. A comprehensive study commissioned by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) highlighted impact assessment practices by non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in 25 sample countries from around the world and concluded that impact assessment practices were developing in all of those 25 reviewed countries.12 Civil society organizations and networks themselves have taken on leadership in this issue, often working in close cooperation with academic institutions to strengthen their methodology on the issue. In India, one such example is PRIA. Building on its expertise in providing development assistance, it has created both online resources and training for civil society organizations, including literature and training on how to measure impact.13

The international development community took on the issue of accountability in the late 1980s, as it attempted to increase its influence on projects carried out by the World Bank, and also, but to a lesser degree, the IMF.14 While the discussions of the past 10 years on accountability have not yet penetrated the majority of regional and national organizations, most large international development organizations have succeeded in collaborating with academic researchers as well as International Finance Institutions to improve their understanding of what works, and of how to report on practices and outcomes.15 Here too, it was not merely a matter of insight into intrinsic values driving the development of techniques for impact and value assessment. Far more critical in pushing this process along was pressure from constituents and taxpayers in democratic societies in some of the large donor nations, to assure that accountability for the resources was committed to development, both at home and abroad.

Finally, humanitarian aid agencies took on the issue of performance measurement when they found themselves faced with a number of challenges to their legitimacy, beginning with the failure of humanitarian aid in Rwanda and continuing with a number of scandals in large international organizations in the early 1990s.16 A perfect example of such publicly inspired progress was the scandal surrounding the effect and effectiveness of child-sponsorship agencies in 1994. An article in the Washington Post triggered public outrage, and an inquiry into the child sponsorship model led to a joint undertaking to create a code of conduct and systems of accountability among child sponsorship organizations. It was the funding constituents, i.e. the thousands of individuals who had pledged donations to sponsor a child, who demanded to know whether their money had had an effect. These challenges led the community of humanitarian aid organizations to engage in very serious discussions on evaluation and accountability.17 Among the most active organizations are Oxfam, CARE, Save the Children, and the ICRC.

A couple of lessons can be learned through these thumbnail sketches of instances in which progress was made towards improved impact assessment. Academics can and do play a vital supporting role, and donors and supporters are not only the triggers but are also often partners in the process; and this process is far from easy. Even a basic agreement for a framework of action and accountability took several years for the child-sponsorship community to reach, but the organizations all agree that they are much stronger for it, providing more value to the children at risk.

Yet despite the increasing pressure and burgeoning literature on the subject, CSOs – particularly in the human rights field – still do not share a “culture of indicators.”18 There is anything but a clear sense among human rights CSOs on what performance measurement actually means, and on how it should be done. While admirable efforts have been launched to promote an exchange of best practices, human rights CSOs have been reluctant to address the issues of organizational effectiveness and impact assessment, leaving each organization struggling to develop an approach on its own.19

Given the pressures outlined above and the increasing attention that other members in the world of civil society are paying to impact assessment, why is it that most human rights organizations have stayed on the fringes of the discussion for so long? One factor is surely that the academic and practitioner communities in the field of human rights have been busy forming a clarification of the mandate of human rights organizations; another is the expansion of the frontiers of what is considered to be their scope. Although some, including Amnesty International, are now turning their attention to the issue of measurement,20 many human rights organizations are still actively engaged in redefining their role in the world. To the extent that these organizations are now reaching conclusions,21 the time is ripe for discussions on measurement, as they must decide how they will pursue their newly clarified missions.

There are, however, a host of other challenges that the human rights movement faces in tackling the measurement issue, some of which are specific to the human rights field, others of which are shared by any CSO.22 The general obstacles that all civil society organizations face include:

• Balancing donors’ demands with organizational needs. Due to the pressure from donors on the issue of measurement, many organizations have been forced into a kind of redundant bookkeeping, in which they must report along the fairly narrow project-focused guidelines suggested by their funders, and keep track of their impact on the constituencies they consider to be most helpful. Hence they end up with two sets of metrics: one for the donor, and another for themselves.

• Adapting private-sector tools to the citizen sector. Defining concrete, focused goals and distinct groups of stakeholders is much more difficult in civil society when using evaluation frameworks usually drawn from business. Opportunities for so-called “quantum leaps” which permit organizations to have a tremendous impact, can be hindered by precise advance planning if the original plan had outlined a different course of action.

• Capturing the importance of leadership. While analysts’ ratings of corporations always pay close attention to the personalities leading the organizations, there is a resistance in civil society to acknowledge the importance of the individual in driving social change. Acknowledging the importance of the personal skills needed to make a push for social change goes against the culture of celebrating good-will, and it is exceedingly difficult to factor into impact assessment frameworks.23

• Overcoming the cultural gap. Measurement seems foreign to the culture of the civil society field. Civil society organizations are usually less interested in producing material products than in encouraging better, more inclusive processes. The fundamentally process-oriented goals of civil society organizations are difficult to reconcile with methodologies used in outcome-oriented evaluations.

• Managing scarce resources. CSOs are chronically short of human resources and the time needed for full assessments of the organization’s plans and processes. In addition, because the funder community has not yet broadly realized the importance of building capacity in this area, it remains very difficult to raise money for internal training and organizational development.24

• Overcoming the prevalence of non-systematic impact assessment. Activists generally rely on a gut-sense of effectiveness. The abundance of individual testimonies from beneficiaries often provide a sense of progress that is sufficient enough to give an organization the sense of security it needs to know that it is making a difference. What these testimonies do not reflect, however, is a communication of whether the strategy that was used was the best option available, and/or if any kind of systemic change is represented by these testimonies.

• Addressing language barriers. Most of the literature and support on the topic is in the English language, so that – even if a CSO representatives can speak English – the literature and support are often inaccessible to non-academic readers.25

In addition to these general obstacles to civil society organizations, a list of the specific difficulties faced by human rights organizations in tackling the issue of internal progress assessment is long enough to give pause to even the strongest-willed advocate of the importance of measurement:26

• Balancing transparency and security. In certain circumstances, transparency on methods and techniques can endanger organizations that work in high-risk environments. Human rights advocates in many countries where, arguably, their work is most needed, regularly face personal threats and organized attempts to shut their organizations down. In these cases, transparency would not only endanger the personal security of individuals, but also compromise the long-term effectiveness of the organization’s campaign.

• Allowing for flexible responses. Human rights organizations often find it hard to plan actions in detail, since the breadth of their mandate forces them to remain flexible to react as issues develop. Unexpected changes and outcomes are a regular occurrence, making linear planning models insufficient.27

• Acknowledging the collaborative nature of advocacy. Given the variety of factors, individuals and institutions that influence any change in systems, it is often very difficult for organizations to take credit for a specific result.

• Empowering others to take credit. Much human rights work is geared toward effecting policy change. In many cases, the government agency or official who needs to make the policy change would be politically and personally compromised if it were acknowledged that pressure from the human rights community played a role in changing his or her mind. In these cases, no matter how certain the human rights organization might be about the immediacy of its effect, claiming it might limit its access to that channel of influence in the future.

• Acknowledging the long-term nature of the impact. Effective advocacy campaigns and human rights interventions must frame their goals with attention to both short-term objectives (e.g. a radio program or a training session on domestic violence) and long-term, transformational, systemic goals (e.g. changing attitudes about women’s rights).

• Accommodating the culture of values-based volunteerism. The human rights movement – particularly in the northern hemisphere – carries a long-standing volunteer tradition; an emotionally motivated support base for whom the talk of measurement and effectiveness is largely irrelevant in their ability to feel like they have “done good.”

• Appreciating the contextual nature of human rights work. It is difficult to compare human rights techniques in different countries, because so much of the work is culturally and contextually specific. Working towards eradication of domestic violence in a society in which women are largely working in their homes will, for example, require very different strategies than in a society in which women have a stronger role and voice in the public sphere.

Instead of constituting arguments against impact assessment as a whole, these points should become design elements and guiding principles in the drive toward creating frameworks for assessment.

The key reasons that the human rights movement should overcome these obstacles and develop a culture of impact measurement are neither to please donors, nor to follow a trend. Instead, human rights organizations should feel impelled to take action and to mainstream the culture of measurement into their systems due to these five reasons, which are intrinsic to the human rights movement:

a. the need for continuous (and growing) support,

b. the moral obligation to fulfill promises made,

c. the need for more collaboration, both regionally and transnationally,

d. the ever-lengthening list of problems that must be addressed, yet a limited base of resources, and

e. the generational changes that lie ahead.

Without statistics on the resources that human rights organizations enjoy, a clear picture is difficult to draw on current trends of support. It is, however, anecdotally clear that human rights organizations constantly feel tightly constrained for financial and volunteer resources. It is also clear that it is part of human nature to feel like the time and resources one dedicates to a cause are making a difference, and that there is hardly anything in the social arena more elating and empowering than the experience of success. Clear goals and indicators for performance, and of impact over time, can play a tremendously important role as tools for motivation and empowerment for both volunteers and potential donors. The reinvigorating of underpaid staff, donors and volunteers for their roles can be achieved if there is a sense that through their work they have contributed to the solution of a problem.

An organization’s success depends on a variety of support: donations of time from volunteers; recognition from those whom one is trying to serve; funds from donors; acknowledgement and actions by policy makers; increased awareness of a specific human rights issue among the general population – in short – positive signs of acknowledgement from stakeholders, who might be called an organization’s community of accountability. Every sign of support that a CSO receives includes the expectation that the CSO will deliver on its promise to be part of a solution. Unless an organization understands just how well it is moving a lever of change, it is not holding itself sufficiently accountable; which indicates that it is falling short in its obligations to its stakeholders.

The most important stakeholder for every human rights organization is the one to whom the human rights organizations hold their primary moral obligation: the population group or set of individuals whose rights they claim to defend. If ten dollars would allow a family of the indigenous population in the Amazon to survive for a month, and one is spending ten dollars on a campaign to defend that group’s rights to the land they live on, the moral obligation one holds to that family – and to all other indigenous Amazonian families – is to make sure that the 10 campaign dollars being spent will get them closer to generating income for that group.

Joint action on a specific topic within a country or region has always been a central element of how human rights organizations work. Due to improvements in communication technology and the globalization of human rights work, there is an intensifying call for collaboration across the globe. In order for such collaboration to make sense, however, it is essential that each organization engaged in a partnership understands just what it brings to the partnership, as well as which of its techniques work most effectively. Each organization entering the relationship must understand (and be able to “sell”) the specific benefits of the toolkits it uses, or be able to recognize the advantages of the other’s approach, and be able to incorporate them into its own. Without a clear sense of how organizations operate or what their key strengths are, it becomes very difficult to divide labor among partners in an effective way.

Human rights activism must be about effective systematic change. In order to leverage scarce resources in tackling ever-growing and increasingly complex problems, human rights organizations must be able to exchange ideas on what strategies and tactics work best. This is quite simple to do on the programmatic level, i.e. on the level of how one literacy program compares with the next in expanding the reach of education. However it is much more difficult – yet necessary – on the strategic and systemic levels, where one must be able to not only assess the direct impact of a certain action, but also the indirect impact of certain activities. Focusing narrowly on the programmatic level can blind one to seeing how the various elements of a problem are interrelated, and to an understanding of which levers must be moved together. A prime example of such interdependency is the issue of child labor and trafficking. Without taking into account what alternatives exist for children who are removed from the workforce, anti-child-labor activism can end up increasing the risk to children of being trafficked.28 As mentioned above, a successful example of cross-issue learning networks brought together by the wish to define roles and responsibilities in eradicating problems might motivate organizations in other fields to follow suit.

The 1980s and 1990s were a boom-time in civil societies and those years witnessed the creation of countless human rights organizations around the world. So it is a given that in the upcoming decade many CSOs will be faced with a transition of leadership. Unless organizations can manage to create structures and processes that are independent of the presence and charisma of their founding individuals, the human rights movement will be facing a large-scale loss of leadership in the foreseeable future. Internal organizational assessment and impact analysis techniques can be a great help in preventing any gaps in the foundations on which an organization stands, and make it much more likely to survive the loss of its original leaders.29

Finally, the question is not one of whether or not internal assessments of performance and measurement of impact will be important in the future. The question is simply whether CSOs in human rights can move out of the defensive position they are in now —in which donors’ demands dictate how CSOs produce evidence of their impact – to a more pro-active one in which CSOs define for themselves what metrics and assessment techniques make sense for their missions. Closing the current gap between the “evaluators” and the organizations in the field can only occur if – and when – CSOs take active steps to formulate what they see as the right approach to assessment of organizational processes and impact in their branch of work.

How can human rights organizations move toward a culture of understanding and one of communicating impact? If the arguments above are convincing, and one were to agree that this is something important for human rights organizations to subscribe to, what are the next steps? There are two separate and key steps that must be taken. The first is a collective endeavor of mapping out the mechanics of specific problems, i.e. understanding an issue’s drivers, and how to most effectively address each driver. The second step is to create models of impact assessment for each individual organization.

In order for CSOs to understand how well they are doing at achieving their goals, they must first understand their organization’s place in the broader context of problem-solvers. Collaborative problem-mapping is an important exercise in enabling individual organizations to understand their role in effecting broader societal change. As an example, take the problem of human trafficking. Hundreds of organizations in just as many countries are targeting the issue, but they certainly do not operate within a framework of understanding what all the factors that drive the numbers of trafficked persons are, nor how they can be addressed. Therefore, when an international network of CSOs began searching the online portal of Changemakers.net for the best practices in the field of human trafficking <changemakers.net>, their first step was to break the problem down into problem drivers and strategies. This is but one possible way of framing the issue, but the mere fact that this collaborative practice was begun and helped to organize thinking about different tactics and strategies sets a precedent for future work.30

The beauty of any such map is that it can structure a discussion on long-term, systematic collaboration in a way that is not otherwise possible. How important is each driver in a given context? What are the sources of information and data-collection techniques for measuring change? What are the different strategies to address each sub-piece? How much do they cost? Which strategies address multiple drivers? Which pieces of the problem are currently being entirely under-addressed?

Developing, refining and adapting these problem maps to specific contexts can and should involve academics and foundations in addition to CSOs. Academic researchers can play important parts on several levels: in collecting data on the relative importance of each driver; in creating a framework for data collection and interpretation; in researching best practices; and finally, in helping to build capacity based on the lessons gleaned from all this research. Foundations can play a role by supporting and encouraging these collaborative endeavors, and then by applying the lessons they have learned to their funding strategies. But it is the CSOs who, out of their will to effect social change, must drive this process. Many previous initiatives have failed to take off because CSOs perceived them to be driven by the wrong institutions (i.e. donors and private sector firms). Other fatal flaws have included overly “managerial” language; a focus on technicalities; and a failure to account for the importance of values. Some such initiatives have encouraged CSOs to undergo a process of introspection in order to achieve more legitimacy and accountability outside their immediate networks of supporters and beneficiaries —for example, with governments or businesses – which many CSOs see as secondary to their goals.31 Only when seen as a tool for improving collaboration, and for maximizing the leverage of the scarce resources available in the field of human rights, will this process be able to succeed and take root.

This kind of problem-mapping provides a context for an organization’s own internal impact assessments. Each organization must ask itself how effective it is in addressing the rights issues it has identified as its area of concern. Now that the problem has been mapped, how do we fit it into the landscape? The point is not just to create metrics or to encourage lip-service to performance assessment. It is to help in creating a well-rooted culture of impact measurement, by developing a tool that will enable human rights organizations to guide themselves through the culture-changing process.32

When making suggestions on how human rights organizations across the field should think about performance measurement, it is wise to listen to the query of the doubter, who asks: “Why do we need a collaborative approach to mapping problems or on the framing of our thinking on organizational effectiveness and impact measurement? Will that not inadvertently encourage competitiveness in a field that relies for its strength on inter-organizational alliances? Is self-evaluation not something that organizations should do – as they please – on an individual basis?” The answer to this query must be a resounding “no,” because CSOs that are serious about tracking their impact, and serious about maximizing their effectiveness in achieving real societal change, need to know how they fit into the broader civil society mosaic of their chosen topic area. What is more, only a collaborative effort, with the buy-in of role models and the leading organizations in the field, can give individual CSOs the standing they need in order for donors to take their views on self-assessment seriously. When demonstrating their impact to donors and critics, only cooperation will allow CSOs to move from a defensive position to a proactive one. And finally, collaboration will minimize the effort each individual organization expends as it attains expertise in self-evaluation.

It is also illusory to deny that competitive forces are at work, even in the field of human rights. Not all approaches to a specific problem are created equal. Although comparisons invariably look like those of apples-to-oranges, some organizations are more effective than others, and some strategies work better than others. If 50 CSOs are committed to helping victims of domestic violence, for example, there will be a large variation among them as to what strategies they use and how effective they are. Much depends on the change-model, the context, and the individual change-leader, as well as on his or her team. Human rights organizations face competition for resources, so they have to be able to demonstrate to their constituents and to themselves that their approach is among the best of the possible alternatives toward solving the problem. After having grown out of membership organizations, or of being composed of former victims of human rights abuses, this is a cultural leap that will require some time for the organizations and their members to make. But again, the first steps to take are: to acknowledge that there are different levers to be pulled; and that, yes, we must divvy up the work; and to recognize that a clear understanding of the problem is the necessary first step towards understanding our effect on it.

“There are many roads to Rome” in developing an impact-assessment framework. What we are describing here can not serve as a full-fledged how-to guide. Instead, this is intended to serve as a tool for building institutional momentum and as a model for organizations in the field of human rights as they embark on their process of developing such tools. The core of this idea is that impact indicators cannot, and should not, attempt to be created out of thin air. Once an organization has taken time to figure out how the problem is structured it can embark on the journey toward impact indicators, which by necessity consists of three distinct stages. First is the evaluation of the organization’s mission (or strategy), its network of support, and its operations. The second stage consists of defining the indicators that capture the organization’s performance in these three areas. Finally, the third stage involves the creation of a mechanism for reporting and feedback that will allow for learning throughout the broader regional and international communities of human rights organizations. Ideally, if an organization is doing its job well, indicators of good organizational performance will feed into the overall map of the problem to correlate with the projected and expected effect on one of the drivers of the rights-related issue.

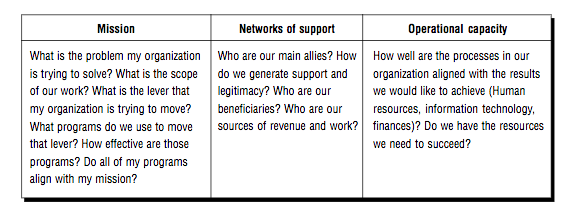

The proposed model for guiding an organization through this evaluation level is based on what is known as the “strategic triangle,”33 which highlights the three key dimensions of any change-oriented social organization which must be aligned: the mission and its values; the support network that the organization will draw upon in the service of the mission; and the organization’s operational capacity in meeting its goals.

Many organizations claim to have what they call performance measurement techniques, and yet have not undergone the series of necessary analytic steps to make sure that they are actually measuring impact, and not just tracking activity. Relying on what has been called a “cherished theory of change,”34 many organizations do not have a refined understanding of their agency, and of the effects of their work. Instead, they produce voluminous reports on how many women they have counseled or children they have enrolled in school, without truly understanding whether those activities actually helped achieve their ultimate goal of reducing domestic violence and increasing literacy rates. In the field of measurement, the message from experts is clear: evaluation systems that are not closely tied to clear mission statements and an understanding of what impact the organization aims to have are doomed to failure.35 CSOs interested in self-evaluation must first of all define their mission statements.

It is important to underline the value of preceding this mission review with a collaborative discussion on how the problem breaks down, so that the mission’s discussion can be defined within the context of a community of organizations, and a multitude of successful strategies. Having clearly defined the mission’s scope, the challenge is to evaluate the activities of the organization by using a criterion of whether or not (and how effectively) they contribute to achieving the defined goal. Mission clarification is a time-consuming process requiring the participation of the whole organization. Only then will the process be driven by a vision of the higher contribution to the public good; thus it will be a project in which all members of the organization are willing to participate. After all, performance measurement is not an on-again off-again process, but a deep change in the culture and reporting style of the organization that can take several years to implement.36

Human rights organizations rely on a variety of sources, not only for funding but for moral support, recognition, and the legitimacy needed for their policy suggestions to have an effect. Understanding how well the organization is supported and what determines the degree of support it receives must be part of any analysis of its effectiveness and impact. If, for example, membership is declining, yet revenue is growing, the organization should analyze the underlying forces behind those trends – which could be anything from the loss of broad popular appeal of the issue, to a decline in membership outreach activities due to the successful recruitment of a major donor. Any organization that depends on a narrow number of donors and does not have a broad base of citizen support risks losing touch with the people whom it is trying to serve. It also risks falling short in its responsibility to raise awareness among the local population of the problem it is trying to solve. Thinking creatively about how to mobilize resources – whether monetary, volunteer, or in-kind – allows organizations to not only diversify their funding base, but encourages them to rethink their outreach strategies.37

Finally, an organization must take a close look at its internal structure and resources, to determine whether it has enough financial and human resources to accomplish the objectives it has defined. Here, too, lurks a common trap: that of simplifying this analysis into the relationship of “overhead costs” to “program costs”. For many organizations in the field of human rights (and in the social sector as a whole) the “overhead” might mean where the most value is created, i.e. the people, their skills; their activities might be exactly where the most mission-related impact is achieved. Therefore the analysis of capacity should focus on the organization’s ability to combine its capital, its human resources, and its knowledge, in a way that maximizes the amount of impact it can deliver.38

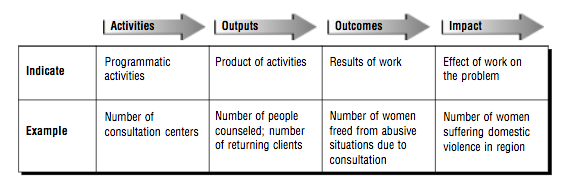

Once a CSO has completed the first evaluative step – having clarified its mission and reviewed the resources and support it can call upon in the service of that mission – the organization can move to step two: defining indicators that capture the nature of the progress it hopes to achieve. These indicators must be sensitive to the four specific levels of activity that lead to impact: activities, output, outcomes and impact (see chart below).

On the levels of activities, outputs, and outcomes, finding indicators of progress is quite straightforward once the process of clarifying one’s mission has been completed.39 The CSO must simply make sure that indicators of performance and impact are based on a clearly demonstrable relationship between the organization’s activities and the realization of its goals, as described in the mission statement.

Considerably more challenging is the development of indicators for the last stage: impact. Yet it is the impact stage that really shows how successful the organization will be at achieving its ultimate mission. The impact indicators at the end of this chain must be relatively simple, and it is advisable to pick just four or five strong indicators; and not give in to the temptation of creating a long list of issues and indicators that the organization is trying to affect. These are the numbers that the organization will use to communicate its impact to the outside world. They should impart a perception of the degree to which the organization has been able to affect policy, to change minds, to affect lives. An ongoing evaluation of impact will most likely need to include qualitative and quantitative elements, and incorporate the viewpoints of a variety of stakeholders, including the organization’s staff, the beneficiaries, and the supporters of the organization. Only through a combination of numbers and stories can the richness of an organization’s impact on society be captured.

This is obviously the hardest set of indicators to define, and the one that must strike a balance between wanting to define societal impact and the need to be honest about agency. As pressure toward impact metrics grows, some organizations might feel themselves pressured to claim impacts they can not even be sure they had. A nonprofit dedicated to building inner-city playgrounds, for example, was pressured to create a link between its play spaces and combating juvenile obesity – a tenuous link at best, and one that no one in the organization felt comfortable with. Many of the long-term changes in the field of human rights are equally difficult to track. How does one measure a change in attitudes and shifts in values, even before the policy has changed? Would one need to declare the campaign to end the death penalty a failure, for example, simply because capital punishment still exists in the US? Or could one point to the fact that much has changed in how the courts are limiting the use of capital punishment, and celebrate the possible changes that a campaign against it might bring in the medium term? Here, much research needs to be done – and some is already underway – to find guidelines for capturing impact measurements on some of the human rights programs that are most difficult to track.40

The most neglected role in the literature on performance measurement and organizational effectiveness is the important part that can be played by learning communities. CSOs do not need to solitarily embark on self-assessment endeavors. First, there are networks of academics and consultants with long experience in self-evaluation in both the for-profit and the not-for-profit fields, and they can help CSOs think through in greater detail what sorts of self-evaluation templates would suit them best. Secondly, CSOs have much to learn from one another. Regular communication and exchanges of experience between CSOs undergoing the same processes can be extremely helpful, not only for avoiding a repetition of mistakes, but also to share in the positive learning that occurs. Again, as mentioned above, foundations can and must play a major role in making this kind of learning possible. It is critical to the human rights community to have funders functioning as partners, not as remote donors.

Proposals for impact assessment, as put forward here, rely on different justifications. This paper suggests that human rights impact assessments must be internally motivated, and driven by a desire to answer these questions: “What is your organization trying to achieve, and how? How does it fit into the broader field of CSOs working on this problem? Is your organization strengthened on a daily basis through knowledge of how it is succeeding at moving the levers of change?”

In addition, it is critical to reconceptualize the space for the impact measurement discussion. It may not be allocated solely, or even primarily, into the realm of donor-grantee relations. Instead, the issue of impact assessment is a matter that primarily affects relationships between CSOs, as well as between organizations and their constituents. Far too often the reasons for impact measurements that fall through the cracks are neglecting the need for cooperation and an organization’s failure in its moral responsibility to do the best job it possibly can.

The various steps proposed are not simple, nor are they steps that will be completed in a short period of time. But if the expected return were not so great, this daunting process would certainly not be worth proposing. The price that is being asked of the movement is an investment of some time, and to put some shared thinking into a joint effort – together with the relevant academic community – on:

a. creating maps describing the drivers of specific human rights problems and discussing the strengths and co-dependency of the various strategies used to target them;

b. creating a template for the self-assessment of effectiveness that human rights organizations can use to understand how effectively they are addressing the problems they have identified as their own.

The return that improved measurement techniques might bring is no less than an increase in collaboration; an invigoration of the members of the human rights movement; more donor support, and accelerated social change. What could be more worth an investment of resources and time?

1. On this phenomenon, first detected and mobilized by Ashoka—Innovators for the Public, see the excellent study by David Bornstein, How to change the world: Social entrepreneurs and the power of new ideas, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2004.

2. J. Shapiro, Monitoring and Evaluation Toolkit, CIVICUS, 2004, available at <www.civicus.org/new/media/Monitoring%20and%20Evaluation.doc>.

3. Some of the most recent works include Jessica E. Sowa, Sally Coleman Selden, and Jodi R. Sandfort, “No Longer Unmeasurable? A Multidimensional Integrated Model of Nonprofit Organizational Effectiveness,” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 33:4, Dec 2004, pp. 711-728; J. Cutt, and V. Murray, Accountability and Effectiveness Evaluation in Nonprofit Organizations, London, Routledge, 2000; Robert S. Kaplan, “Strategic Performance Measurement and Management in Nonprofit Organizations,” Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 11:3, Spring 2001, pp. 353-370; and Christine Letts, William P. Ryan and Allen Grossman, High Performance Nonprofit Organizations: Managing Upstream for Greater Impact, New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1999.

4. See Hugo Slim, “By What Authority? The Legitimacy and Accountability of Nongovernmental Organizations,” The Journal of Humanitarian Assistance, 2002.

5. The issue of who is responsible for delivering on the promise of human rights has just recently become a focus of analysis and debate. See, e.g., Andrew Kuper, ed., Global Responsibilities: Who Must Deliver on Human Rights?, New York, Routledge, 2005.

6. For a good discussion on the transfer of for-profit models into the nonprofit sector see Rob Paton, Jane Foot and Geoff Payne, “What Happens When Nonprofits Use Quality Models for Self-Assessment,” Nonprofit Management and Leadership 11:1, Fall 2000; and Robert S. Kaplan, op. cit., 2001.

7. On the Hewlett Foundation’s self-analysis, see the “Grantee Perception Report,” Center for Effective Philanthropy, 2003, Available at

8. See, for example, the research conducted internally by United Way, “Agency Experiences with Outcome Measurement: Survey Results,” United Way of America, 2000.

9. See Center for the Study of Global Governance (LSE) and Center for Civil Society (UCLA),Global Civil Society Report, London, Sage Publications, 2004; Christine Letts, et al., op. cit.; Robert Kaplan, op. cit.; and Jessica E. Sowa, et al., op. cit., pp. 711-728.

10. Academic Journals dedicated to performance evaluation include Evaluation and Program Planning, American Journal of Evaluation, Evaluation Practice, New Directions for Program Evaluation, Educational Evaluator and Researcher, the Evaluation Exchange. The research and writing on these subjects and trends have, however, neither literally nor conceptually been translated into non-English speaking markets.

11. Not only have the leading strategy consulting firms begun offering their assistance (usually pro-bono) in this field (See, for example, the report by McKinsey&Co. “Effective Capacity Building in Nonprofit Organizations,” report prepared for Venture Philanthropy Partners, August 2001, <http://www.vppartners.org/learning/reports/capacity>. New companies have sprung into this niche, including Bridgespan (a spin-off of the consulting firm Bain & Co.), Givingworks, and New Sector Alliance.

12. Searching for Impact and Methods: NGO Evaluation Synthesis Study. A Report Prepared for the OECD/DAC Expert Group on Evaluation. Helsinki, 1997.

13. <http://www.pria.org/cgi-bin/index.htm>

14. Jonathan A. Fox and L. David Brown, The Struggle for Accountability: The World Bank, NGOs and Grassroots Movements, Cambridge: MIT Press, 1998 2ff.

15. L. David Brown and Mark H. Moore, “Accountability, Strategy, and International Nongovernmental Organizations,” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 30.3 (2001): 569-587. See also Tina Wallace, Standardising Development, Oxford: Worldview, 1997.

16. Margaret Gibelman, Sheldon R. Gelman, “Very Public Scandals: Nongovernmental Organizations in Trouble,” Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, Vol. 12, No. 1, 2001.

17. The late 1990s witnessed a tremendous amount of activity among humanitarian organizations on this issue, spawning a number of large international initiatives focused on creating a code of conduct (SPHERE, see

18. See Nancy Thede, “Human Rights and Statistics: Some Reflections on the no-Man’s Land between Concept and Indicator,” Statistical Journal of the United Nations ECE 18, p. 2001, 269-70.

19. The Geneva-based International Council on Human Rights Policy has conducted two major research efforts on the issue of measurement and accountability in the field, with reluctant engagement from CSOs (interview Mike Dotteridge, March 10, 2005). The Center for Victims of Torture has developed a “New Tactics” program aimed at gathering and sharing ideas for ‘best practice’ approaches to specific challenges in the Human Rights field, which includes only one example of internal assessment techniques (DANIDA). See

20. Amnesty International, for example, is undertaking a movement-wide effort to establish an approach to impact assessment. See internal report: AI²: Assessing AI’s impact for Human Rights, 2005.

21. See, for example, the internal debates at Oxfam and Amnesty, as discussed in Claude E. Welch, NGOs and Human Rights: Promise and Performance (Philadelphia, 2000)

22. For an analysis of some of these barriers see Christine Letts et al., op. cit., p. 32-35.

23. The largest network of leading social entrepreneurs, Ashoka, places great emphasis on these individual qualities in its selection process and then maps impact by analyzing the idea’s reach, including how many organizations have replicated the idea and whether it has affected national policy. See <www.ashoka.org/global/measuring.cfm>.

24. An exception to this is the field of support for individual leading human rights advocates and social entrepreneurs. For instance, Ashoka, Reebok and the RFK Memorial Foundation all partner with their fellows and awardees to work on these issues.

25. Some of the rare exceptions to this are the “tools” provided by Civicus for CSOs (

26. Some of these factors are listed in a presentation by Dr. Linda Kelly, “International Advocacy: Measuring Performance and Effectiveness,” paper presented at the 2002 Australian Evaluation Society International Conference, Oct./Nov. 2002.

27. Alan Fowler, “Assessing Development Impact and Organizational performance,” in Alan Fowler, Striking a Balance, Earthscan: London, 1997.

28. Interview with Mike Dottridge, March 8, 2005.

29. Hugo Slim, “By What Authority”, p. 109.

30. See, for example, the work done by Ashoka fellows on the issue of human trafficking: <endtrafficking@changemakers.net>.

31. See for example the elaborate undertaking by the Keystone (formerly ACCESS) coalition around creating reporting standards for nonprofit organizations around the world, to make the effectiveness of organizations more comparable to potential investors. See <http://www.accountability.org.uk>.

32. A number of compendia of analytical tools and models already exist, outlining a broad array of diagnostic checklists and elaborate frameworks, some looking like enormous spider-webs, some looking like the switching system for Victoria Station, some even presented as three dimensional cubes. See, for example, P.F. Drucker, The Drucker Foundation Self-Assessment Tool: Participant’s Workbook (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1998); James Cutt and Vic Murray:Accountability and Effectiveness Evaluation in Non-Profit Organizations, London/NY: Routledge, 2000.

33. This framework appears in several forms, including the “strategic triangle” described in Mark H. Moore, Creating Public Value, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996, and the “value, capacity, and support three circles model,” described in Herman B. “Dutch” Leonard, “A Short Note on Public Sector Strategy-Building,” Kennedy School of Government research report/working paper, 2002.

34. I owe this term to S. “Dutch” Leonard.

35. This argument was made with particular force by John C. Sawhill and David Williamson, “Mission Impossible? Measuring Success in Nonprofit Organizations,” Nonprofit Management and Leadership, Spring, 2001.

36. The average time to implementation is quoted in one study as requiring 3.5 years. Rob Paton, Jane Foot, and Geoff Payne, “What Happens When Nonprofits Use Quality Models for Self-Assessment?” Nonprofit Management & Leadership 11:1, Fall, 2000.

37. For an example of a global attempt to encourage more citizen based resource mobilization see

38. For a recent, very comprehensive compendium of research on performance evaluation systems see Wholey, Joseph et al, Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation, San Francisco, 2004.

39. This analysis has also been given a variety of names, from “logic frame” to a “theory of change.” There are a number of frameworks aimed at alleviating these processes of connecting activities to the mission through a series of stages and of creating corresponding indicators. Among the most popular are the “Theory of Change Model” (Frumkin), and the “Logframe” (i.e. logical framework) model. On the theory of change model see Peter Frumkin, On Being Nonprofit: A Conceptual and Policy Primer. Harvard University Press, 2002. The “logframe”, or logic frame model (which was initially developed by USAID) has become increasingly popular among foundations, who encourage their grantees to map their work along this framework. As such, it has so far remained not in internally motivated, but a donor-driven process that does not provide the necessary level of institutional engagement and learning. These are discussed at length in chapter one of Wholey et alii, op. cit., 2002.

40. Two of the most ambitious international impact measurement endeavors currently underway are the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy’s Measurement and Human Rights program, see <www.ksg.Harvard.edu/cchrp>> and the OECD’s Metagora Project, see