Analysis of the informational struggle in the 2022 elections

Disinformation is a serious and complex problem for modern democracies. On the one hand, it demands criteria and state standards for its confrontation, on the other hand, it demands attention in relation to the protection of freedoms and the guarantee and promotion of a healthier and more inclusive digital environment. This short reflection analyzes the Brazilian elections of 2022 in relation to the odyssey that was to face disinformation, in a context of intense polarization and democratic threats.

The 2022 elections were certainly a significant moment in the history of misinformation in Brazil. The election campaign and the extreme right´s forays into the use of misinformation as a political strategy sparked important movements on digital platforms, by civil society and officials, seeking ways of combating the problem which has been undermining democracies worldwide. In understanding this situation, it is useful to think in terms of three different moments: the groundwork, warming up the engines and then the acceleration that led to emergency actions.

We must bear in mind that the 2018 elections in Brazil left a legacy. While this legacy did not necessarily allow for robust solutions concerning the matter of misinformation, it did at least mean this was at the centre of the debate from the outset. Precisely because of this, groundwork was laid before the elections. To this end, the Superior Electoral Court (TSE) sought the digital platforms, established a constant dialogue with them and signed partnerships and memoranda of understanding with Twitter, TikTok, Facebook, WhatsApp, Google, Instagram, YouTube, Kwai and Telegram. In other words, terms had been agreed upon, albeit insufficient ones, regarding what should be done during the elections.

This important move seemed to be working at the beginning of the 2022 political campaign. Up until the week before the first round of voting, the view prevailed that misinformation was under control and was having little impact, as had been seen in 2018. The 48 hours prior to the first round though revealed that this was not the case. Rapid actions were being carried out, taking advantage of the gap in communications, i.e. once the free election broadcasts had concluded and there were no longer any rallies. There was also some leniency on the platforms and delays in legal rulings. An example of this was a video stating that the drug trafficker Marcola had said he would vote for Lula. It remained online for 16 hours, from 8.30pm on the eve of the first round until 12.30pm on the polling day.11. "TSE manda Bolsonaro e sites apagarem que Marcola vota em Lula: ’Inverídico’", UOL, October 2, 2022, accessed December 31, 2022, https://noticias.uol.com.br/eleicoes/2022/10/02/tse-marcola-lula.htm.

Once we moved to the second round of voting the information battle became even more heated, completely changing any impression that things might be calm. The president of the TSE, Alexandre de Moraes, stated at a meeting with Google, Kwai, LinkedIn, Meta, TikTok, Twitch and Twitter that the situation with misinformation was a disaster.22. "Moraes fala em desastre de fake news no 2º turno e quer poder de polícia ao TSE", Exame, October 20, 2022, accessed December 31, 2022, https://exame.com/brasil/moraes-fala-em-desastre-de-fake-news-no-2o-turno-e-quer-poder-de-policia-ao-tse/. One of the main points raised by the minister was the need to remove content more quickly in response to judicial rulings.

On this point, there appeared to be two kinds of problems. Firstly, the policies of the platforms were insufficient to handle several aspects of misinformation, such as those linked specifically to the candidates and insurgency. Secondly, the terms that had been announced and agreed upon with the TSE were not being fully applied. Online political propaganda that had been banned on the election day of the first round was still available; content that had been flagged by the Court had not been removed and known spreaders of misinformation had not been punished. These irregularities were signalled in a series of reports published at the time. We would like to draw particular attention to the series of studies produced by Netlab, at UFRJ.33. Available in university archives: "Conteúdos", Netlab, 2022, accessed December 31, 2022, http://www.netlab.eco.ufrj.br/publicacoes.

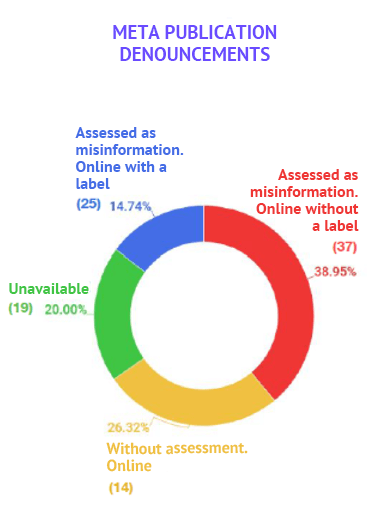

For example, the graph below shows that almost 40% of the posts thought to be problematic on the Meta platform remained online, without any kind of label.

Source: Netlab/UFRJ (2022).44. "Conteúdo nocivo: a Meta protege a integridade eleitoral no Brasil?", Netlab/UFRJ, October 7, 2022, accessed December 31, 2022, https://uploads.strikinglycdn.com/files/6d84bff4-bbaa-4073-993f-d4efb2c69b73/Elei%C3%A7%C3%B5es%202022%20-%20Conte%C3%BAdo%20nocivo%20a%20Meta%20protege%20a%20integridade%20eleitoral%20no%20Brasil_Netlab.pdf.

This situation led to the TSE taking some emergency measures. They concentrated authority on themselves, allowing the Court to act in an ex officio capacity against misinformation. They increased bans on online advertising for 48 hours before and 24 hours after the voting and extended rulings on content removal to identical copies of original content. Now the election process is over, actions like these certainly merit ample discussion. The concentration of power on a single body, in this case the TSE, was important as an immediate reaction, but may not be the best option in the long term. The complexity of the matter calls for an examination of the pros and cons in order to ensure different and possibly conflicting points of view are heard. Moreover, misinformation is not limited to election periods. What will happen when the TSE is no longer at the centre of legal actions? These and other points need to be discussed to find the most democratic ways possible of handling decisions on what warrants public debate and what does not. However, throughout the campaign, these actions proved to be important and effective in combating growing misinformation. In an election as disputed as this one it would have been a tragedy if misinformation had been responsible for swaying the result, by basing it not on the desire of the electorate but on the creation of a false notion of reality.

However, it is important to say that it remains a challenge to identify the precise impact of misinformation on voting decisions. While observation of patterns of communication provide indications it is hard to establish a correlation. This difficulty also arises from the fact that the digital environment has profoundly changed how political campaigning is done and this goes far beyond misinformation. Means of communication, of creating political facts, mobilising electorates and influencing agendas are others and this is still unfamiliar territory in a country that is accustomed to television-based campaigning. It is no coincidence that a political player like André Janones has drawn attention on the left, precisely because he understands and uses this approach to communication. The question now is: what actually are the parameters that should guide digital political communications in order to produce more and not less democracy?

The 2022 elections have certainly left us some clues. Firstly, the model of self-regulation on digital platforms does not work alone. It requires national parameters that must be adhered to as well as mechanisms for transparency, monitoring and accountability. Secondly, the lack of legal parameters, which should be built collectively and as a result of broad social debate, means emergency rulings and swift actions, that may be controversial, are left in the hands of the Judiciary. Thirdly, a civil society that is active and trained to handle digital issues is absolutely essential to ensure monitoring and social pressure, in order for these parameters to be continuously improved. Fourthly, the role of serious journalism in producing quality information and nurturing trust in institutions is a further essential pillar in this cause.

With the new government starting now and the pause in the anti-democratic threat that has been hanging over Brazil, we see a challenge to build pathways to consolidate a healthy, plural and democratic digital space, ensuring rights and curbing the use of this space to falsify reality. Certainly, this means that the issues of gender and race must be treated as structural and transversal to any discussions on digital issues. More now than ever before, the digital world is a very real aspect of our lives which means historic inequalities in our society are also pervasive in the digital world and must be treated as such.

Furthermore, the new government leads us to believe it will favour the matter of misinformation and the debate on regulations for the digital environment.55. Liz Nóbrega, "Em discurso de posse, ministro da Secom fala sobre combate à desinformação e liberdade de imprensa." *desinformante, January 4, 2023, accessed January 4, 2023, https://desinformante.com.br/pimenta-posse-ministro-secom/. This suggests there will be an intensification of the debate on the regulation of digital platforms which will certainly demand a large mobilisation on the part of those who research and work in this area. The fine line that separates an escalation in the fight against fake news, the discourse of hatred and misinformation, and the protection of rights such as freedom of expression and privacy, is not an easy one to draw, but this is now essential in any society that is truly democratic.

Finally, I believe it to be strategic to refocus the conversation: misinformation is an essential but partial aspect of the problem. At a deeper level the debate we are trying to establish on a daily basis is how to build a healthier more inclusive digital environment and structures and forms of digital appropriation that allow us to strengthen and improve democratic mechanisms.