An experience from Colombia

Interview with Juan Carlos Chindicué

By Sur Journal

Indigenous communities see the Indigenous Guard as their own ancestral organisation and an instrument of resistance, unity and autonomy in the defence of their territory and their plan for life. It is not a system of policing, but rather a humanitarian and civil resistance mechanism. It seeks to protect and promote their ancestral cultural and compliance with their own law. It gets its mandate from the assemblies themselves and therefore, it answers directly to indigenous authorities.11. "Componente Guardia Indígena,” Consejo Regional Indígena del Cauca, (n.d.), accessed July 31, 2020, https://www.cric-colombia.org/portal/proyecto-politico/defensa-vida-ddhh-cric/guardia-indigena/.

Defending land and territories in a country like Colombia is not an easy task. Colonial violence and updated versions of “development” continue to have devastating effects on the territory and indigenous peoples. The internal war that dragged the country through more than 60 years of displacements, hunger and death has affected the indigenous, peasant and black peoples the most. And it is precisely these peoples that are leading resistance, collective organising and different ways of defending their rights.

The Indigenous Guard is a collective and voluntary effort to defend life through the administration of their own law,22. Judicial system proper to indigenous peoples. peaceful resistance, the use of indigenous legislation, the defence of human rights and the promotion of peace in territories marked by violence.

In a short, but fruitful dialogue with Juan Carlos Chindicué, member of the Indigenous Guard from the department of Cauca (a region with a predominantly indigenous population, mostly from the Nasa ethnic group), Sur Journal spoke with one of the many faces of the ancestral struggle to defend the lives and autonomy of indigenous peoples in Colombia.

Sur Journal • How was the Colombian Indigenous Guard created?

Juan Carlos Chindicué • The Indigenous Guard is from a long time ago, when it was the civil guard. From the times of La Gaitana33. La Gaitana was a 16th-century indigenous heroin, a Timaná cacique in the Colombian Andes who led her people in the fight against Spanish invaders between 1539 and 1540. and Quintín Lame.44. Manuel Quintin Lame (1880-1967) was a Colombian indigenous leader who fought for the land and the identity of the Paez or Nasa people. He inspired several struggles, including the Quintín Lame armed movement, an indigenous guerrilla movement that was active from 1984 to 1991. Back then, it was called the civil guard and it controlled and was in charge of the logistics of certain events; as collaborators from the community who supported the cabildos55. Cabildo is a special public entity made up of members of an indigenous community, who are elected and recognised by the community itself, and that has a traditional socio-political organisational form. Its purpose is to legally represent the community, exercise authority and carry out the activities that the law attributes to it and in accordance with the uses, customs and internal regulations of each community. “Cabildo Indígena,” Mininterior, (n.d.), accessed July 31, 2020, https://www.mininterior.gov.co/content/cabildo-indigena#:~:text=Es%20una%20entidad%20p%C3%BAblica%20especial,atribuyen%20las%20leyes%2C%20sus%20usos%2C. and indigenous reservations. That is what the civil guard did back then.

We were included in the Constitution of 1991 as an indigenous movement.66. In the new Constitution of 1991, Colombia is recognised as a pluri-ethnic and multicultural state. The constitution contains provisions on the protection of indigenous communities. After the El Nilo massacre [in which 21 indigenous people were killed],77. The El Nilo or Caloto Massacre was an attack on indigenous people from the Nasa ethnic group in the municipality of Caloto in the Cauca department on December 16, 1991 by members of the Colombian national police and armed civilians. See: “El Nilo”, Rutas del Conflicto, (n.d.), July 31, 2020, https://rutasdelconflicto.com/masacres/el-nilo. the guard began to take shape. During that time, in 1993 and 1994, many young people, women, children and adults joined the guard. But they didn’t have much strength nor did they have a strong structure to sustain the Indigenous Guard. And the organisational process eventually weakened. In 2001, the Indigenous Guard reappeared and resumed work on what was still pending. That year, the movement grew in strength, with approximately 3,000 Indigenous Guards. It started working on building strength within the indigenous territories, as Indigenous Guards, Kiwe thegnas [caretakers of the territory], to control the territory and the plan for life: to protect life. From that year on, the guard has grown stronger.

The national Indigenous Guard was also born from the indigenous Minga.88. On October 12, 2008, between 45,000 and 60,000 indigenous people from different ethnic origins, mostly from the Nasa ethnic group, came together to march approximately 120 kilometres, from Santander de Quilichao, in the Cauca department, to Santiago de Cali, in the Valle del Cauca department. One of the points defended by the Minga was the recognition of the Indigenous Guard at the national level. The government accepted this demand from the indigenous movement and today, we are recognised at the national level, as is the “Cimarrona guard”.99. Translation note: The “Cimarrona Guard” is the guard of Maroon communities. 1010. “Guardia Indígena y Cimarrona: Una Vida de Resistencia,” Pares, March 21, 2020, accessed July 31, 2020, https://pares.com.co/2020/03/21/guardia-indigena-y-cimarrona-49-anos-de-lucha/. The ministry has yet to recognise the peasant guard, but the process is underway. With all the peoples together, there are around 33,000 or 34,000 Indigenous Guards in all of Colombia.

Sur • Tell us about yourself, the history of your family and community in the Indigenous Guard

J.C.C. • I was born in this city [Cali]. I’m not from an ancestral territory. I was born in this city and I studied here. When I was around 18 or 19 years old, I looked for a way to go to the Cauca department, especially the northern part, to find my roots. The impulse to do so came from my [indigenous] last name. I began my journey on this path to community involvement in northern Cauca, namely in the Toez reservation in Caloto. I got involved in the cabildo, the Cauca youth movement and I joined the Indigenous Guard. That is where I felt this impulse to become a guard. At first, for me, it was just a distraction, but once you’re on the inside, you start training to be a guard, you start to understand the organisational process… That is when the desire to carry the bastón [the colourful staff of the Indigenous Guard] is born. One starts to appreciate the process, the bastón, the Indigenous Guard. And well, that was how my community involvement began.

After a problem in my family, I returned to the city. Here, in Cali, I started working for companies. I still keep the memory of what I learned in Cauca alive and try to strengthen it, but there was a time when I was becoming disconnected from the issue of indigenous organising. And so, I started going to a place called El Parque de las banderas, here in the city of Cali, where almost all our people meet. Our people: [indigenous] men and women meet up once every eight days. I had the opportunity to get to know many comrades in this park, to integrate and interact with one another. To hear stories. Some comrades would tell us about the problems they were having in the city. Every eight days, I met more and more comrades who were living in the city.

During that time, I had the opportunity to meet a group of women who had a foundation and were working on the issue of “home workers”. That’s what they call it because the expression “domestic workers” makes it sound like you’re domesticating women, doesn’t it? This is why they changed the name to “home workers”. So, I went to help the foundation, which was headed by one of the women, who was the president (one of the founders), Carmen Rosalba Gurrute Sánchez, who is now my partner, my wife and the mother of my children. We got to know each other in this process of meeting every Sunday. Now, she’s my wife and the mother of my children. We’ve been together for almost 12 years. That is when the family and community process began.

My oldest son, Sekyu Chindicue Gurrute, was born in our ancestral territory, the Totoró indigenous reservation (Eastern side). His mother has been passing all this wisdom, this knowledge of the indigenous organisational process, on to him. On this journey, Juan Diego Chindicue Gurrute [their second son] was also born. We were unable to organise it so he would be born in indigenous territory, so he was born in the city of Cali. From then on, all four of us began going out.

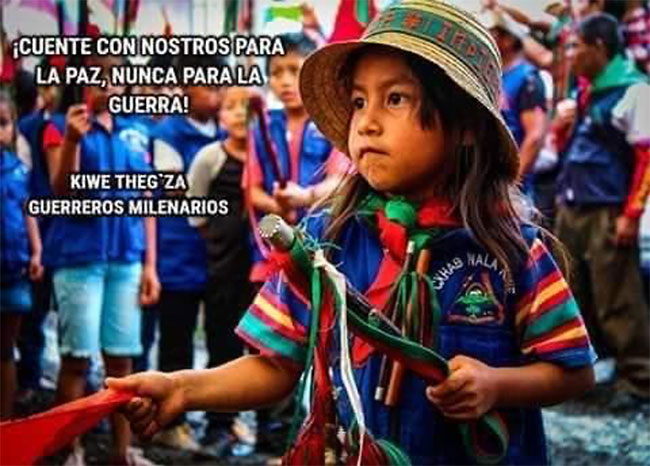

We’d take Sekyu to the marches. We’d carry him on our backs. The same with Juan Diego. They never knew what a stroller or a playpen was. None of that! Ever since they were little, since they learned to walk, we involved them in the guard and the community process. As time goes by, they are developing their own symbolism through their vests, their batons, their scarves. 1111. The “bastón”, their baton or staff, is a symbol of the Indigenous Guard. Natalia Márquez, “Resistencia Pacífica: Este Es El Poder del Bastón de Mando en El Cauca.” Pacifista, September 7, 2018, accessed July 20, 2020, https://pacifista.tv/notas/resistencia-pacifica-este-es-el-poder-del-baston-de-mando-en-el-cauca/#:~:text=Lo%20llaman%20bast%C3%B3n%20de%20mando,es%20un%20s%C3%ADmbolo%20de%20paz. Little by little, they are making themselves known and their training as Indigenous Guards is becoming more visible, not only in the city, but also in Cauca and in other parts of the country. They are children who are laying the ground for the Indigenous Guard because back then, there was little talk about children. [Our children] were pioneers. Many children would see them with their vests and staffs and started taking an interest in the issues of family, the community and the organising process. We’ve set an example as a family on the issue of the Indigenous Guard.

We continue to follow this teaching and we haven’t stopped. On the contrary, we strengthen it every day.

Sur • Tell us about the significance of the bastón or the staff that members of the Indigenous Guard carry.

J.C.C. • The insignia of the ceremonial staff [a 80-cm long staff made from a chonta tree] is a sacred symbol in the indigenous cosmovision. It is a connection, a bridge of energy, a source of spiritual connection.

The power of the staff is that it symbolises authority and indigenous autonomy. Many staffs are decorated with red and green ribbons. “Red represents the blood that has been shed in this millenarian process and green, beautiful and diverse nature”.1212. “El Bastón de Kiwe Thegna Nos Motiva a Unirnos en La Resistencia,” Consejo Regional Indígena del Cauca, October 16, 2019, accessed July 31, 2020, https://www.cric-colombia.org/portal/el-baston-de-kiwe-thegna-nos-motiva-a-unirnos-en-la-resistencia/.

For us, the Nasa people, in the case of the men, the staff is our companion, our confidant, our wife, the one who accompanies us, who whispers in our ear and guides us. When a woman carries it, the staff is her companion, the one who accompanies her, protects her, guides her and whispers to her. In this sense, this symbolism is important because we have learned to respect both men and women. To value each other and respect each other, knowing that no one is more, nor less than anyone else. We are equal.

Thus, the staff is a symbol of authority, defence and resistance, but we will never use it as a weapon. The ceremonial staff is the insignia of the indigenous movement, which calls for unity and resistance as indigenous people.

Sur • How do you view yourself as a human rights defender?

J.C.C. • I don’t have a degree, like other comrades who graduated in human rights, who have studied between four walls, who have degrees and diplomas to show to the UN. I’m not one of them. For me, the fight for human rights was born on the street. Together with the same community that we’ve gone to defend against evictions, abuses from authorities such as the police and the army, or the municipal and departmental government. We have fought “tooth and nail” for them. We have been there for indigenous and Afro-peasant communities almost 24/7.1313. 24 hours a day, seven days a week. So, it was the communities we have supported and backed that gave us our credentials. And thanks to the credentials that they’ve given us, the institutions such as public and state forces have recognized our participation as human rights defenders.

This has not been an easy task because my family and I, we’re volunteers. We devote ourselves day and night to the well-being of these communities, especially indigenous peoples. We give it all we got out on the groundwork. Being a defender hasn’t been easy. I’m one of the ones who have been threatened several times. I’ve received written threats. I’ve been physically threatened and the government ignores us. We have always been denied protection from the state. But despite all that, we advance, we continue on with the confidence that we’ve always had. For example, I take public transportation, ride motorbikes, mass transportation, on the bus, in a “Jeepeto”1414. Editor’s note: The interviewee is referring to Willys Jeeps and other four-wheel drive vehicles that have become a common (and economic) way of transporting goods and passengers, especially in rural areas in Colombia. , walk. I go out at any time of the night, knowing that I’ve done things right, for the well-being of a community.

This is why the request that we make is: more support. More support from the state, more support from authorities, more support from people and the community. Most people say that we, human rights defenders, are making a profit, we’re getting rich or something like that. In my case, I’m a volunteer. No one pays me to do this. I do it with a lot of care and a lot of love; I’m 100% committed. I live humbly. I pay rent like everyone else, but this does not stop us from appropriating this issue. As a human rights defender, as an indigenous leader, as an Indigenous Guard, which all of use from the different indigenous organisational processes are.

Finally, I would like to thank you for the space and opportunity to give visibility to the issue of the Indigenous Guard because we are all the Indigenous Guard! Not only the ones who wear the vest, the scarf or carry the staff; we all are. That is the strength of the indigenous movement or the structure of the indigenous movement. We will always defend life, no matter who it is, regardless of colour, no matter what! We are defenders of life and we will continue defending the territory and we will continue defending our communities and we will continue defending our symbols in the indigenous organisational process.

Interview carried out by Maryuri Mora Grisales in July 2020.

Count on us for peace, never for war!

Kiwe Theg’Za

Millenarian warriors

Photos from Juan Carlos Chindicué’s personal archive.