By Conectas Human Rights

In November 2009, Conectas organized the ninth edition of the International Human Rights Colloquium, whose theme was: “An Appraisal of the Global Human Rights System from a Southern Perspective: Common Strategies and Proposals for Reform”. The Colloquium is an annual event held since 2001 in São Paulo (Brazil) designed, primarily, for young activists from the Southern Hemisphere, completely carried out in three languages (English, Portuguese, and Spanish), that facilitates dialogue between different work agendas of the human rights movement, addresses the latest topics through a multidisciplinary focus, and creates spaces for establishing cooperation between all of the participants.

In the last eight editions, from 2001 to 2008, the Colloquium has welcomed 529 participants from 59 countries in Latin America, Africa, and Asia. Furthermore, 226 people have attended as lecturers and collaborators. In addition to its training mission, the Colloquium plays an important role in the development of policy capabilities of human rights defenders participating in this event and provides the opportunity for participants to expand the scope of their work, to establish connections with networks and groups in other regions.

The ninth edition of the Colloquium sought to bring together a group of young activists and scholars to collectively appraise the efficiency of the international human rights system from a southern perspective. For the first time since its creation in 2001, the IX Colloquium gathered ex-participants from previous editions of the event, exclusively. Thus, the meeting sought to strengthen collaborative work between different generations of participants. The working methodology sought to create a propitious space for developing future strategies for action and concrete proposals for reform in the multilateral human rights system.

The group, which gathered participants from all of the colloquia, also carried out an evaluation of the results from the previous eight editions of the Colloquium and discussed the format and content of the 2010 and 2011 editions.

The meeting gathered 34 participants from 22 countries (14 men and 20 women) from Latin America (14), Asia (4), and Africa (16). It also received 32 observers and support from a team of 14 volunteer monitors for the organization. From the event’s selection process until its conclusion, the participants completed a series of readings and preparatory coursework on the themes addressed in the program.

Hosting the IX International Human Rights Colloquium was possible thanks to generous contributions from the Open Society Institute, the Ford Foundation, and the United Nations Foundation. It also received support from the French and Canadian Consulates, OSISA, and Ashoka Social Entrepreneurs. As in previous years, the Getulio Vargas Foundation Law School welcomed the event for a week and the Ruth Cardoso Youth Center, of the Municipality of São Paulo, received the participants during the inaugural session.

The participants requested that the present review of the event be published in the Sur Journal to inform those who formed a part of previous editions of the Colloquium and other interested persons.

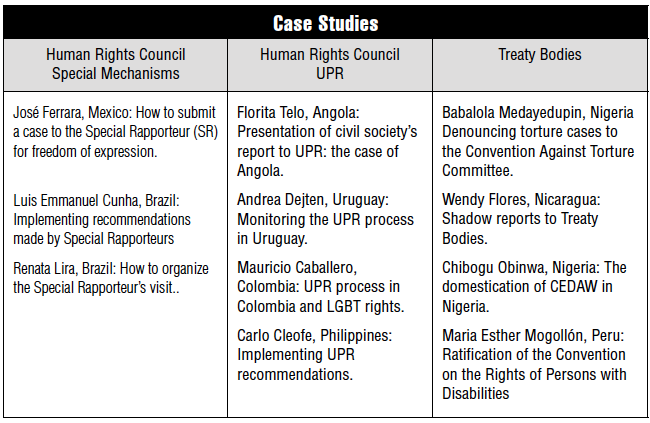

This year’s program sought to provide a general panorama of the functioning of the main UN human rights mechanisms and, at the same time, encourage discussions of concrete strategies for joint action and proposals for reform. Thus, each one of the mechanisms analyzed (the UN Charter system and the treaty system) was studied from three perspectives: Conectas was responsible for providing an overview of its functioning, a speaker was invited to formulate a critical view, and, finally, the participants presented concrete examples of their use. There were 11 practical presentations that illustrated the difficulties that activists have found in using these mechanisms. During the group work, the participants discussed some strategies for overcoming challenges and formulated concrete proposals for reform.

The group of lecturers and panelists gathered academics, activists, and UN officials who analyzed the operation of UN bodies from a human rights perspective and discussed opportunities for civil society participation.

The Program placed special emphasis on UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) mechanisms and treaty bodies. As a result, Camila Asano of Conectas presented the political context of the UNHRC and Philippe Dam of Human Rights Watch (Geneva) discussed resistance from UNHRC member states to adopting resolutions on countries. Lucia Nader of Conectas presented an overview of the functioning of Universal Periodic Review (UPR) and Sandeep Prasad of Action Canada for Population and Development – ACPD (Canada) presented the challenges involved in including the issue of sexual rights in UPR. Mustapha Al- Sayyid, from Cairo University, spoke about the role of Arab countries in the Human Rights Council. Julia Neiva of Conectas described the functioning of treaty bodies, and Gabriela Kletzel of the Center for Legal and Social Studies – CELS (Argentina) presented her organization’s experience in presenting shadow reports.

Two Special Rapporteurs also participated: the UN Special Rapporteur on Arbitrary Executions, Philip Alston, sent a video explaining the work of special mechanisms, and the UN Special Rapporteur on Adequate Housing, Raquel Rolnik, spoke about her one-year experience as a Special Rapporteur, and shared the challenges of combining field work with the institutional requirements of the United Nations.

June Ray of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (Civil Society Unit, Geneva) and Katherine Thomasen of the International Service for Human Rights (Geneva), presented opportunities for civil society to effectively participate in the United Nations system. June Ray emphasized the role of the OHCHR as a bridge between human rights defenders and different United Nations bodies.

Two other topics were discussed: the Security Council and the International Criminal Court, respectively by Joanna Weschler, from the Security Council Report (USA), and Camila Maturana, from the Humanas Corporation (Chile). Both gave an overview of the functioning of these international institutions and explained how NGOs can monitor their work.

Some participants presented their experiences in engaging with the international system to illustrate the lectures. This methodology, used for the first time during the colloquium, made the discussions more horizontal, and allowed a true exchange of experiences between the participants.

José Ferrara, of the Miguel Agustín Pro Juárez Human Rights Center (Mexico) told his organization’s experience in using a UN special report, in the context of civil society’s preparation of shadow reports for UPR. He therefore affirmed “sending information to the Rapporteur was convenient for forming a part of the broad strategy involving the media and organizations dedicated to defending freedom of expression. Our approach found an echo among the diverse delegations that were present during the appearance of the Mexican delegation. The activism of international organizations linked to the subject was also helpful.” He added, “in sending information to the Rapporteurs, it is important for the information sent to be highly trustworthy, and for it to propose the actions it wishes to ask the States to take.” Finally, he recommended, “that the information sent form a part of a broad strategy that includes the committed mobilization of diverse social sectors.”

Luis Emmanuel Cunha, of Gajop (Brazil) presented his organization’s experience in developing a methodology for evaluating the implementation of recommendations from the UN system. Luis highlighted the difficulty faced in evaluating compliance with recommendations from different UN mechanisms, due to the fact that each one of the mechanisms drafts recommendations in accordance with its own criteria, impeding the creation of a uniform procedure for analysis.

Regarding the visits of the Rapporteurs, Renata Lira of Global Justice (Brazil) emphasized the importance for the reports delivered to the Rapporteurs during the visit to be drafted in English, and to have official statistics, emblematic cases, and, above all, a contextual political analysis. She also stressed the importance of organizing meetings with victims and their family members so that the Rapporteur may have a vision of the country’s actual situation.

Florita Telo, from the Mosaiko Cultural Center (Angola) told of an experience in drafting a civil society report for UPR. The report was developed by 10 organizations from different regions in Angola. They worked fundamentally around six themes: the right to housing, to education, health, indigenous peoples’ and rural communities’ land rights, access to natural resources, freedom of association, and freedom of assembly and expression. In her presentation, Florita emphasized the additional difficulty faced by activists who speak Portuguese, since this is not one of the official languages of the UN.

Andrea Dejten, of the Interdisciplinary Center of Development Studies (Uruguay) gave an account of how, upon beginning to participate in UPR, organizations realized that they were in a sort of haze with respect to this new, novel, and participative mechanism, but they still did not fully understand it. At the same time, the government called for civil society collaboration in drafting the official report. From Andrea’s viewpoint, this process of consultation and information on UPR in Uruguay suffered from a series of difficulties, among them, the scarce and selective call for an organized civil society, executed with insufficient time for ensuring the broadest participation, and with scarce information that would allow for civil society organizations to carry out a proper analysis for drafting a position. Finally, Andrea mentioned that a good idea for the future would be to announce a permanent round table for the next review.

Mauricio Caballero from Diverse Colombia (Colombia) presented a project for including the issue of LGBT rights in the UPR of Colombia. Mauricio began by emphasizing that UPR represents various difficulties. First, the mechanism was new, unknown, and with unclear rules. Second, he mentioned that the issue of homosexuality is a subject that generates controversy and division within the Human Rights Council. Third, he highlighted that Colombia is a complex country, with a great number of serious human rights problems, which makes it very difficult to incorporate all subjects.

The result of the organization’s work was positive, since the UNCHR included a specific recommendation on the subject that was assumed by the State and, thus, the first explicit international recommendation regarding LGBT human rights in Colombia. Mauricio explained that the recommendation has been used to strengthen internal debate. This recommendation has been important for generating spaces for dialogue with the government and other international mechanisms (Inter-American Commission on Human Rights) and in internal litigation (Constitutional Court). It has been also useful to strengthen public policies regarding the rights of this segment of the population, especially to strengthen the normative framework and to create indicators of the effective enjoyment of these rights.

Carlo Cleofe, of the Task Force Detainees of the Philippines (Philippines), mentioned that for the civil society report to UPR to be taken into consideration, they were worried about ensuring that the information appeared trustworthy, so they called for a wide spectrum of organizations to sign the document. He also emphasized that being able to participate in the Council’s session twice was very important in order to speak with the delegations about the country’s review. In these visits, parallel events were also organized, which helped to generate interest regarding the situation in the Philippines. Finally, Carlo highlighted that it was fundamental for the delegations to have drafted a list of recommendations to their country in advance: of the 19 delegations that were gathered, 11 used the recommendations drafted by civil society.

Babalola Medayedupin, of the Center for Community Development and Conflict Management (Nigeria) gave an account of the difficulties that her organization faced in trying to internationally denounce a serious case of torture, due to the fact that Nigeria had not ratified the Protocol to the Convention Against Torture. Therefore, she emphasized the importance of studying, while preparing a case, which treaties the country in question has ratified.

Wendy Flores Acevedo from the Nicaraguan Center for Human Rights (CENIDH) (Nicaragua), explained her organization’s experience in presenting alternative reports before the different treaty bodies of the UN, such as the Human Rights Council in October 2008, the Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights in November 2008, and the Committee Against Torture in May 2009. As the main lesson learned, Wendy emphasized the necessity of working together with other organizations with the goal of gathering broad and complete information. She also mentioned the need for setting dates for presenting reports on the part of the State and for programming reviews of the different bodies. The main challenge identified was the importance of constructing a working methodology for drafting a report in coordination with other organizations. She suggested, as a mechanism, appointing a small group of drafters to be responsible for compiling the information and writing the final draft so that the document may have consistence, harmony, and a unified language.

Chibogu Obinwa, of BAOBAB for Women’s Human Rights (BAOBAB) (Nigeria) commented on her organization’s experience surrounding implementation in the internal environment of the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). She pointed out that Nigeria ratified the Convention during the military government in 1985, and that it never really incorporated it internally. Chibogu also mentioned that the internalization of the Convention faces some difficulties, based on contrary cultural stereotypes of women’s rights. Thus, the strategy of a broad collation of organizations was to draft a very well documented shadow report on 16 articles of CEDAW and to participate in the Committee’s sessions in New York during the evaluation of Nigeria. Chibogu went on to state the importance of maintaining informal dialogue with CEDAW members to call attention to the most important points that should be questioned of the government. On the other hand, as strategies for the implementation of the Convention, she mentioned the media’s role in presenting which aspects of the legislation need to be reformed, and in training judges and legislators on the subject.

María Esther Mogollón, of the MAM Foundation (Peru) presented her experience in the efforts for the approval of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. María Esther had the opportunity to inform the position of the Peruvian government, following a prior investigation that she had carried out concerning the sexual and reproductive rights of persons with disabilities, especially the right to maternity of disabled women. Even though Peru voted in favor of the Convention and subsequently ratified it, Maria Esther denounced a diminishing trend in protecting the rights of persons with disabilities in her country.

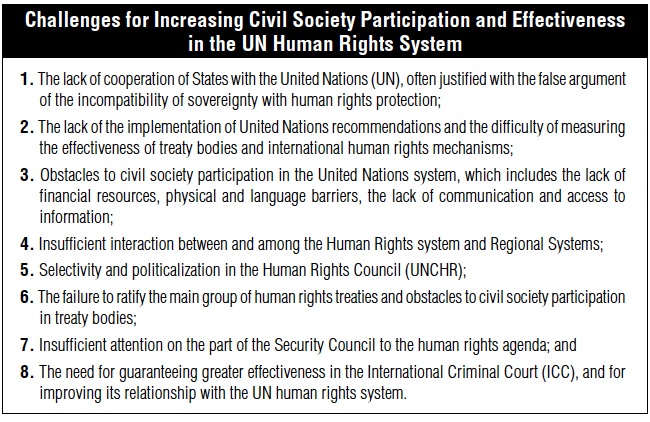

During the work groups, the participants actively collaborated in order to produce a joint statement on the following challenges faced by the United Nations human rights system:

The work groups made recommendations directed towards the UN, governments, and civil society organizations. Conectas presented, in the name of all of the participants, the Final Document to the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, and all participants presented the document to their respective governments (in their countries as well as in their respective delegations in Geneva). Conectas also distributed the document through its website and newsletter. The complete version of the final document may be found at: www.conectas.org/arquivospublicados/IXColoquioDDHH_DocFinal_Espanol.pdf

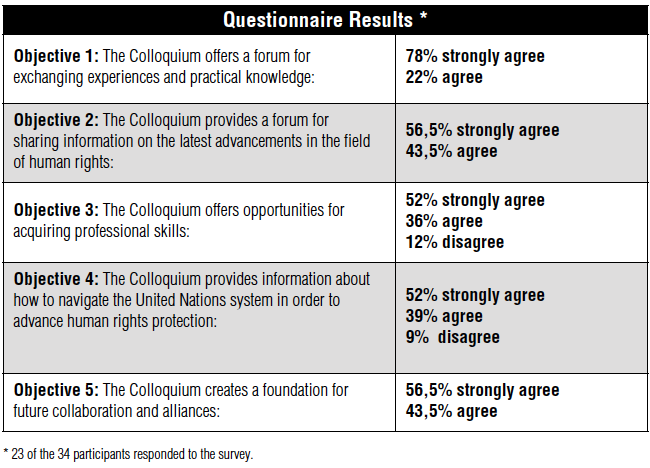

In previous years, Conectas has carried out evaluations with the participants in the Colloquium, during and after the event, and has taken the results of these evaluations into consideration in order to introduce changes and improvements in its format and content. These consecutive evaluations have shown that the Colloquium has been transformed into a recognized space in which human rights organizations, especially from the Global South, may conduct capacity-building and create networks. Nevertheless, Conectas wished to have a more substantial evaluation from the beneficiaries of the different editions of the Colloquium, as regards to its impact.

Taking these evaluations into consideration, the IX Colloquium gathered 34 participants from the 8 previous events. This was the first time that the participants of different generations had the opportunity to meet each other and create links for future joint activities. Moreover, they could give their opinion with respect to the content and format of future editions of the Colloquium.

Conectas requested that the participants contribute to the evaluation process in three phases: i) responding via internet to a questionnaire prior to the event; ii) discussing the results of the questionnaire during the Colloquium, y iii) drafting proposals for future editions.

During the preparatory stage, the participants were requested to give their opinion on the degree of compliance with the five objectives that the Colloquium seeks to achieve.

The survey showed a very positive evaluation of the Colloquium. 100% of the participants “Strongly agree” or “Agree” that the Colloquium: i) Offers a forum for exchanging experiences (objective 1), ii) Provides a space for learning about the latest human rights development (objective 2) and iii) Creates a foundation for future collaboration (objective 5). It is interesting to highlight that those three objectives were also selected in the last part of the evaluation as the main objectives for the Colloquium’s future.

With respect to acquiring professional skills (objective 3), the participants that were of the opinion that this objective was not within reach (voting “disagree”) explained that they disagreed with the manner in which the phrase was presented, especially with the term “acquiring.” With respect to the offer of information about how to navigate the UN system (objective 4), the participants that “disagreed” asked Conectas to organize complementary courses about the UN system. They affirmed that a Colloquium lasting one week was not sufficient for leaning about such a complex system.

During the discussions, the participants made several positive comments. They spoke about the impact of the Colloquium in their lives, giving concrete examples of joint projects implemented thanks to the Colloquium. They also mentioned that the Colloquium is different from other courses, because it takes the social aspect of human rights work into consideration, allowing for the creation of new friendships. In addition, they emphasized its unique character as a South-South forum.

The participants made proposals for future Colloquia, including the incorporation of French as one of its languages, and recommended continuing many of its traits, such as the Open Space Forum (a space for discussion of subjects proposed by participants), Brazilian NGO visits and case studies presented by participants. The participants also recommended that Conectas document the impact that the Colloquium has had in the lives of its participants, affirming that “this story must be told.”

The Colloquium plays a central role in the life of Conectas. Each year, the Colloquium is the moment in which the organization invests its greatest effort. It is, additionally, the main space for hearing the opinion of human rights activists from the Southern Hemisphere, to whom a large part of the organization’s activities are directed.

It was extremely comforting to hear the opinion of ex-participants during the evaluation carried out during the IX Colloquium. In this sense, four aspects are particularly relevant: 1) the recognition of the Colloquium’s being the only event of South-South integration in human rights; 2) accounts of collaborative projects between participants begun following the Colloquium regarding which Conectas didn’t have information; 3) the recognition of the efforts of Conectas in keeping in touch with ex-participants after the Colloquium, and 4) the importance of spaces for socializing during the Colloquium and the recognition of Conectas’ work in creating these spaces for integration.

In light of the results of the evaluation, it is clear that the main challenge for Conectas is to design a tool that allows measuring the impact that the Colloquium has in strengthening a new generation of human rights activists that values collaboration and perceives the difference between North-South and South-South relations.

In order to obtain more information about the X International Human Rights Colloquium that will be held in October 2010, visit: www.conectas.org/coloquio.